WASHINGTON — In announcing executive pay limits on Wednesday, President Obama is trying to hold the financial industry accountable to taxpayers while aiming to change an entrenched corporate culture that endorses outsize bonuses and perks that often bear little relationship to corporate performance.

Multimedia

Blog

The Caucus

The latest on President Obama, the new administration and other news from Washington and around the nation. Join the discussion.

Mr. Obama also needs to deflect a growing populist outrage over sky-high pay among the banks and other companies now on the public dole. His announcement comes just days before the administration is expected to unveil a new strategy — and possibly request more money from Congress — to guarantee or buy outright hundreds of billions of dollars in bad assets held by banks.

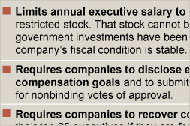

The new rules would set a $500,000 cap on cash compensation for the most senior executives, curtail severance pay when top executives left a company, restrict cashing in on stock incentives until government assistance was repaid and prod corporate boards to closely scrutinize luxury perquisites like private jets and country club memberships.

The plan’s effectiveness in curbing executive pay may not be known for years, however. Past administrations have also been critical of excessive pay, but corporate executives have found ingenious ways around limits, often hiring consultants to create new forms of compensation.

Even the new rules allow companies some leeway. While giving shareholders a say in bonuses above the cap and restricting when stock incentives can be cashed in, the rules do not place limits on the size of such awards, which have become the biggest part of many compensation packages. In addition, the toughest new rules apply only to large companies seeking government assistance to survive.

They do not apply to the more than 350 institutions that have already received bailout funds, only to those that seek aid under the next phase of the bailout program. And companies that seek aid but do not need exceptional government assistance can waive the $500,000 pay cap, as long as they submit their executive pay policies to a nonbinding shareholder vote.

Still, the rules represent the most comprehensive effort to curb compensation. “This is America,” Mr. Obama said on Wednesday. “We don’t disparage wealth. We don’t begrudge anybody for achieving success. And we believe that success should be rewarded. But what gets people upset — and rightfully so — are executives being rewarded for failure. Especially when those rewards are subsidized by U.S. taxpayers.”

In 2007, the latest year that figures are available, the largest participants in the bailout program paid their chief executives an average compensation of $11 million, including salary, bonus and benefits. Of that amount, according to a review by Equilar, an executive compensation firm, only about $844,000 was cash salary. About $2.5 million was in a cash bonus, with the bulk — $7.4 million — in stock awards, and the remainder in benefits and perks.

If banks return to the government for more money, the new rules would require a reduction in pay, but not in stock awards, though these would be subject to a non-binding vote of the shareholders and would be in the form of long-term incentives because of restrictions on when they could be cashed in.

The plan will most likely force companies to think twice before coming to Washington for a handout, and it is certain to nudge them to return taxpayer loans more quickly.

On Wednesday, for instance, David A. Viniar, the chief financial officer of Goldman Sachs, which received $10 billion from the Treasury Department, told analysts that his firm wanted to repay the government as quickly as feasible to “be under less scrutiny and under less pressure,” according to Bloomberg News.

The Financial Services Roundtable, which lobbies on behalf of banks and other financial institutions, said that giving shareholders a vote on pay could discourage companies from seeking aid.

The rules would not prohibit a lower-level executive, like a stock trader or investment banker, from continuing to receive tens of millions of dollars in pay. Officials also emphasized that several of the proposals would not be made final until after public comments had been considered.

Still, investor groups, union leaders and lawmakers in both parties embraced the proposal.

“There is absolutely no reason why hard-working American taxpayers should be financing, directly or indirectly, excessive compensation for corporate executives whose decisions, in many cases, have crippled their firms and weakened the broader economy,” said Senator Christopher J. Dodd, the Connecticut Democrat who heads the Senate banking committee.

Representative John A. Boehner of Ohio, the Republican minority leader, said that pay limits would be more equitable for rank-and-file taxpayers. “If anyone is looking for the taxpayer to help bail their company out,” he said, “these types of executive pay caps are appropriate.”

Officials said that the larger goal of the proposal was to make the boards of major corporations across a wide range of industries award pay packages more consistent with corporate earnings.

Appearing with Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner, the architect of the plan, Mr. Obama repeated a theme that he began last week of attacking Wall Street for its excessive compensation.

“For top executives to award themselves these kinds of compensation packages in the midst of this economic crisis is not only in bad taste, it’s a bad strategy, and I will not tolerate it as president,” Mr. Obama said. He said such pay is “exactly the kind of disregard for the costs and consequences of their actions that brought about this crisis — a culture of narrow self-interest and short-term gain at the expense of everything else.”

During the Bush administration, the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted new rules promoting better public disclosure of executive compensation as a way to discourage pay not tied to performance. Treasury Secretary Henry M. Paulson Jr. also criticized excessive pay as a factor contributing to the crisis on Wall Street and tried to impose some limits on banks receiving bailout funds.

But none of that put a significant dent in executive pay. A recent study by Equilar, a compensation research firm, found that the chief executives of the 10 largest financial services firms in a survey of 200 companies with revenue of at least $6.5 billion were awarded a total of $320 million last year, even though the companies had mortgage-related losses of $55 billion.

Some companies may not find the new pay curbs all that burdensome. The plan does not limit the size of bonuses that can take the form of restricted stock above the $500,000 cap — though companies would have to give shareholders a nonbinding vote on such awards.

Indeed, troubled financial institutions are already giving executives significant sums of restricted stock — shares that are locked up for years and can be sold only under specified conditions — in part because they are trying to preserve cash. Alan Johnson, managing director of Johnson Associates, a Wall Street pay consulting firm, said that in some cases, restricted stock was making up 60 percent of executives’ total compensation.

Mr. Johnson said the new restrictions could make it harder for the government to resuscitate ailing firms by making it harder for them to retain and recruit talented executives.

The plan does not appear to prohibit a financial institution from sponsoring a major golf tournament that most of its executives attend as part of the company’s marketing strategy. At a White House briefing, senior officials repeatedly declined to answer whether the plan would prohibit a company like Citigroup from paying $400 million to have its name on a baseball stadium. It is also unclear whether lucrative pension plans would be banned.

The administration will have to determine how broadly to apply the most severe restrictions as the TARP program is revised. If the new strategy envisions that many banks will be eligible for assistance, as they have in the past, then the less restrictive pay rules would apply to them.