| Hibernating species | ||

|---|---|---|

| Species Name | Common Name | |

| 1 | Myotis auriculus | Mexican long-eared bat |

| 2 | Myotis austroriparius | Southeastern bat |

| 3 | Myotis californicus | California bat |

| 4 | Myotis ciliolabrum | Western small-footed myotis |

| 5 | Myotis evotis | Western long-eared bat |

| 6 | Myotis grisescens | Gray bat |

| 7 | Myotis keenii | Keen's bat |

| 8 | Myotis leibii | Eastern small-footed bat |

| 9 | Myotis lucifugus | Little brown bat |

| 10 | Myotis occultus | Occult bat |

| 11 | Myotis septentrionalis | Northern long-eared bat |

| 12 | Myotis sodalis | Indiana bat |

| 13 | Myotis thysanodes | Fringed bat |

| 14 | Myotis velifer | Cave bat |

| 15 | Myotis volans | Long-legged bat |

| 16 | Myotis yumanensis | Yuma bat |

| 17 | Nycticeius humeralis | Evening bat |

| 18 | Parastrellus hesperus | Canyon bat |

| 19 | Perimyotis subflavus | Tricolored bat |

| 20 | Corynorhinus townsendii | Townsend's big-eared bat |

| 21 | Corynorhinus rafinesquii | Rafinesque's big-eared bat |

| 22 | Eptesicus fuscus | Big brown bat |

| 23 | Antrozous pallidus | Pallid bat |

| 24 | Euderma maculatum | Spotted bat |

| 25 | Idionycteris phyllotis | Allen's big-eared bat |

| Long-distance Migrants/Non-hibernating species | ||

| Species Name | Common Name | |

| 1 | Mormoops megalophylla | Ghost-faced bat |

| 2 | Choeronycteris mexicana | Mexican long-tongued bat |

| 3 | Leptonycteris nivalis | Greater long-nosed bat |

| 4 | Leptonycteris yerbabuenae | Lesser long-nosed bat |

| 5 | Macrotus californicus | California leaf-nosed bat |

| 6 | Lasionycteris noctivagans | Silver-haired bat |

| 7 | Lasiurus blossevillii | Western red bat |

| 8 | Lasiurus borealis | Eastern red bat |

| 9 | Lasiurus cinereus | Hoary bat |

| 10 | Lasiurus ega | Southern yellow bat |

| 11 | Lasiurus intermedius | Northern yellow bat |

| 12 | Lasiurus seminolus | Seminole bat |

| 13 | Lasiurus xanthinus | Western yellow bat |

| 14 | Eumops floridanus | Florida bonneted bat |

| 15 | Eumops perotis | Greater mastiff bat |

| 16 | Eumops underwoodi | Underwood's mastiff bat |

| 17 | Molossus molossus | Pallas' mastiff bat |

| 18 | Nyctinomops femorosaccus | Pocketed free-tailed bat |

| 19 | Nyctinomops macrotis | Big free-tailed bat |

| 20 | Tadarida brasiliensis | Brazilian free-tailed bat |

During the winter of 2006–2007, an affliction of unknown origin dubbed “white-nose syndrome” (WNS) began devastating colonies of hibernating bats in a small area around Albany, New York. Colonies of hibernating bats were reduced 80–97 percent at the affected caves and mines that were surveyed. Since then, white-nose syndrome or its presumed causative agent have been detected more than 2,000 kilometers (1,200 mi) away from the original site, and has infected bats in 17 additional states and adjacent areas of Canada. Most species of bats that hibernate in the region are now known to be affected; little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus), northern long-eared bats (M. septentrionalis), and federally listed (endangered) Indiana bats (M. sodalis) have been hit particularly hard. The sudden and widespread mortality associated with white-nose syndrome is unprecedented in hibernating bats, which differ from most other small mammals in that their survival strategy is to live life in the slow lane: their life history adaptations include high rates of survival and low fecundity, resulting in low potential for population growth. Most of the affected species are long lived (~5–15 years or more) and have only one offspring per year. Subsequently, bat numbers do not fluctuate widely over time, and populations of bats affected by white-nose syndrome will not recover quickly. Epizootic disease outbreaks have never been previously documented in hibernating bats.

White-nose syndrome (WNS) was named for the visible presence of a white fungus around the muzzles, ears, and wing membranes of affected bats. Based upon what is known about typical fungal pathogens of typical mammals, this fungal growth was initially thought to be a secondary infection of bats with compromised immune systems. However, bats are anything but “typical” mammals (see below). Since then, a previously unreported species of cold-loving fungus (Geomyces destructans) has been identified as a consistent pathogen among affected animals and sites. This fungus, now widely considered to be the causal agent of WNS, thrives in the darkness, low temperatures (5–10ºC; 40–50ºF), and high levels of humidity (>90%) characteristic of bat hibernacula. Unlike typical fungi, Geomyces destructans cannot grow above 20°C (68ºF), and therefore appears to be exquisitely adapted to persist in caves and mines and to colonize the skin of hibernating bats. A consistent pattern of fungal skin penetration has been observed in more than 90 percent of bats from the WNS-affected region that were submitted for disease investigation.

White-nose syndrome was first documented in a cave that is visited by tens of thousands of tourists each year, and the disease has since spread outward from that site. The focal area of origin and subsequent distribution of affected sites indicate that G. destructans could be an exotic species with the capacity to spread rapidly among populations of hibernating bats. Researchers in Europe have long noticed similar fungal growth on the faces, ears, and wings of hibernating bats in Europe, but observed no associated mortality. Work is currently underway to assess whether there is any connection between fungi seen on bats in North America and Europe. Recent efforts by researchers in Europe have revealed that G. destructans occurs on hibernating bats in several countries of that continent. An alternative hypothesis for the origin of white-nose syndrome is that this fungus was already present in North America, yet recently mutated to become an emerging disease.

Pathologic findings thus far indicate that bats affected by white-nose syndrome are infected by G. destructans, and many appear to prematurely run out of the stored body fat that they rely on for winter survival. Species of bats occurring at the higher latitudes of the world rely on insects for food, which disappear from those temperate zones during winter. Most species of temperate zone bats survive the winter by building up fat reserves during autumn and then going to cold places to hibernate and wait out the winter insect shortage. During hibernation, a bat slows down its metabolism so that its body temperature remains just a few degrees above air temperature. This strategy allows a bat to consume very little fat over winter. Bats could easily last several months in this deep state of torpor, but they need to warm their bodies up a few times each winter and arouse from hibernation so that they can drink, urinate, mate, relocate, and probably induce their immune systems to catch up. These natural arousals from hibernation consume a lot of energy, and about 90 percent of a hibernating bat’s winter fat is burned to fuel natural arousals. If anything increases the frequency or duration of such arousals during winter, the energy balance of a hibernating bat can quickly tip toward starvation. Chronic disturbance of hibernating bats is known to cause abnormal arousal patterns, and can result in high rates of winter mortality. For example, certain inappropriate research methods (e.g., poorly applied wing bands and frequent winter visitations) directed toward hibernating bats in the 1950s and 1960s caused chronic disturbance that led to high mortality and population declines in several U.S. bat species (Ellison 2008). Unlike typical microbial pathogens that cause collapse of internal organ systems, the skin infection caused by G. destructans may act as a chronic disturbance during hibernation, and fungal-associated aberrant behaviors likely cause bats to consume critical body reserves too quickly during winter. In addition to disrupting hibernation cycles and prematurely expending energy reserves, it is likely that affected bats suffer other serious physiological problems (e.g., dehydration) associated with the fungus infecting the proportionally huge skin surfaces of their wings during hibernation.

The newly identified cold-loving fungus is now thought to be the primary causative agent of white-nose syndrome. Available evidence suggests the fungus establishes itself in the skin tissues of bats when their body temperatures are lowered during torpor (2–10ºC; 35–50ºF). Although life-threatening cutaneous fungal infections of this sort are rare in warm-blooded birds and mammals, they occur more frequently in “cold-blooded” animals (e.g., chytridiomycosis in amphibians, and crayfish plague). The cold-loving fungus seems to be infecting bats when they reduce their body temperatures during hibernation to levels characteristic of “cold-blooded” animals. Fungal infiltration of the wing membranes of bats may be particularly problematic. Wing membranes represent about 85 percent of a bat’s total surface area and play a critical role in balancing complex physiological processes. Healthy wing membranes are vital to bats, as they help regulate body temperature, blood pressure, water balance, and gas exchange—not to mention the ability to fly and to feed. Although white-nose syndrome was named after the obvious sign of white noses on affected bats, bat wings may indeed be the most vulnerable point of infection.

Because the newly identified fungus represents a potential biological invasion or emerging disease, with severe implications for hibernating bats in North America, it is important to focus on the history of its geographic distribution in the context of the distributions of affected species and those of federal concern that are potentially in harm’s way.

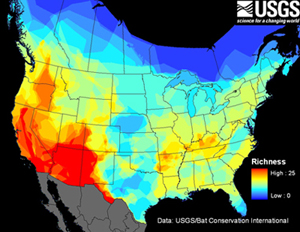

Forty-five species of bats occur in the United States and Canada, and bats represent more than 10 percent of mammalian species diversity in the region. The map at right shows bat species richness in the continental United States and Canada. Warmer colors represent higher species richness, cooler colors represent fewer species.

More than half of the species of insectivorous bats that occur in the U.S. rely on hibernation as a primary strategy for surviving the winter when insect prey is not available. The table at right lists all 45 species of bats known to occur in the continental United States and Canada. Species in the upper list are those that in most areas rely on hibernation to survive the winter. Species in the lower list are those that generally do not rely on hibernation as a winter survival strategy. Those highlighted in yellow text are species currently known to be affected by white-nose syndrome.

The emergence and spread of a pathogenic fungus that infects hibernating bats has the potential to undermine the basic survival strategy of more than half the bat species in the U.S. and all species of bats that occur in the higher latitudes of North America. With the exception of 4 species of migratory tree bats, the other 18 bat species that occur above 40ºN in North America (roughly a line running from the top of California across Nebraska to Virginia) hibernate to survive the winter.

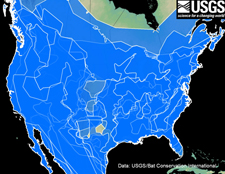

The shaded red areas on the map below represent the overlapping distributions of 19 species of bats occurring in the U.S. that do not rely on hibernation as a strategy for surviving the winter. The blue shaded areas of the map below represent the overlapping distributions of 25 species of bats occurring in the U.S. that rely on hibernation to survive the winter. The distributions of four species of migratory tree bats are not shown.

|

|

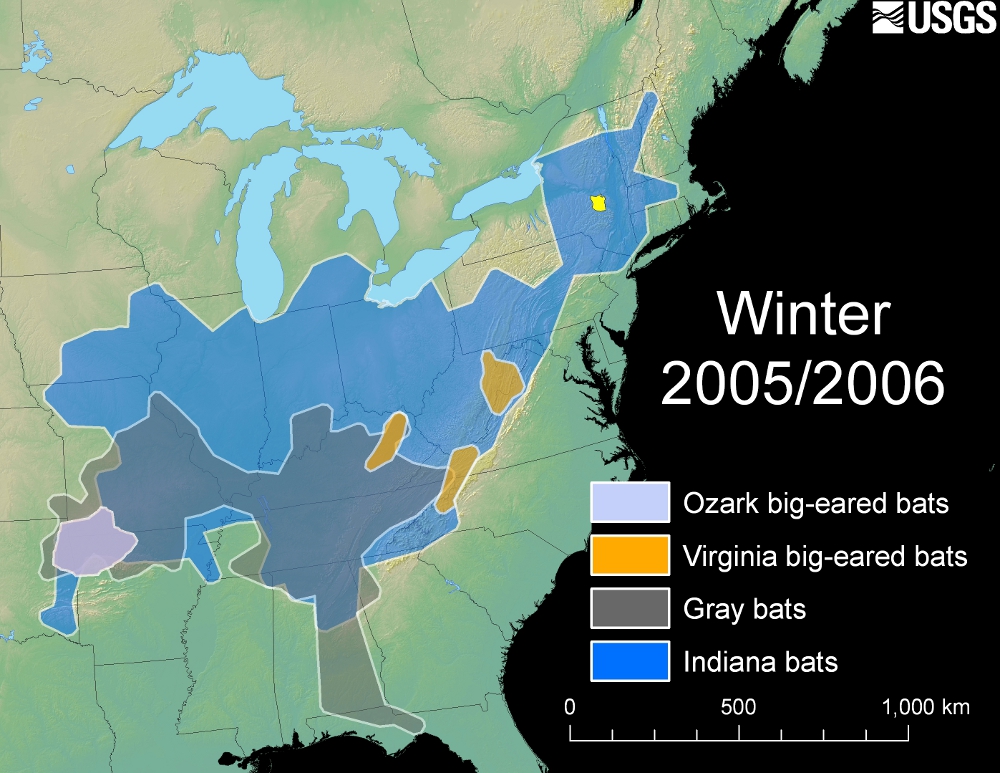

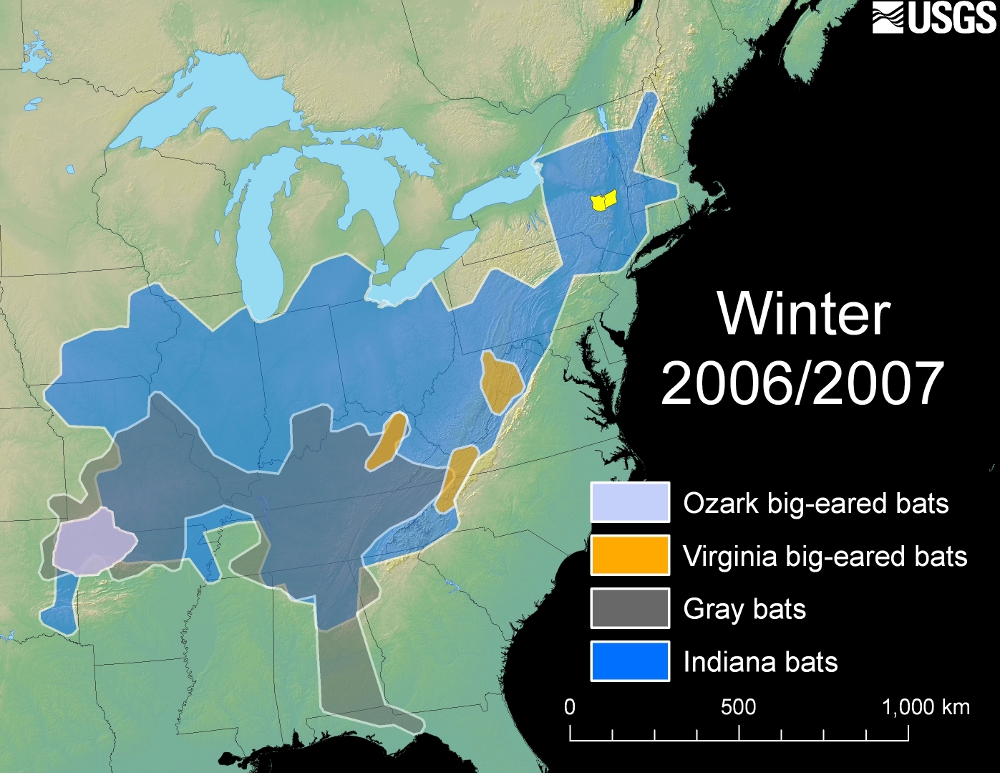

Among the 25 species of bats that hibernate across North America, 4 species and subspecies are federally listed as endangered and an additional 13 are federal species of concern (former Category 2 candidates for listing under the U.S. Endangered Species Act). All four endangered species and subspecies of hibernating bats in the U.S., which rely on undisturbed caves or mines for successful hibernation, are at risk from white-nose syndrome. Three of these species are currently within the affected area, and the remaining subspecies may be affected in the next few years, if not sooner.

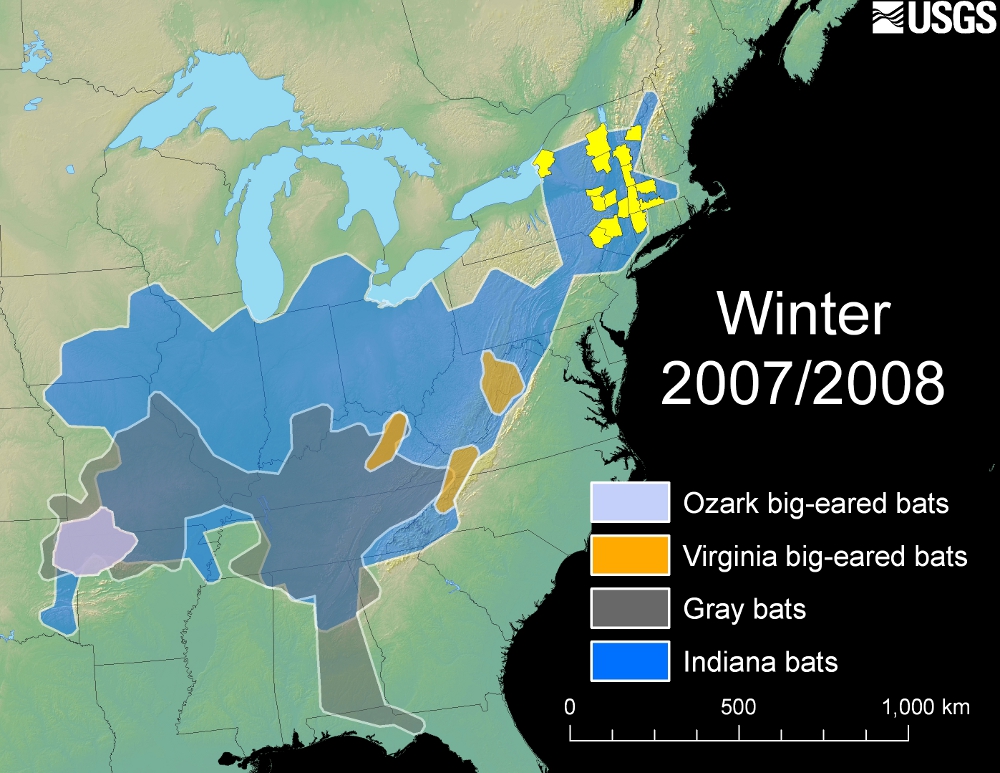

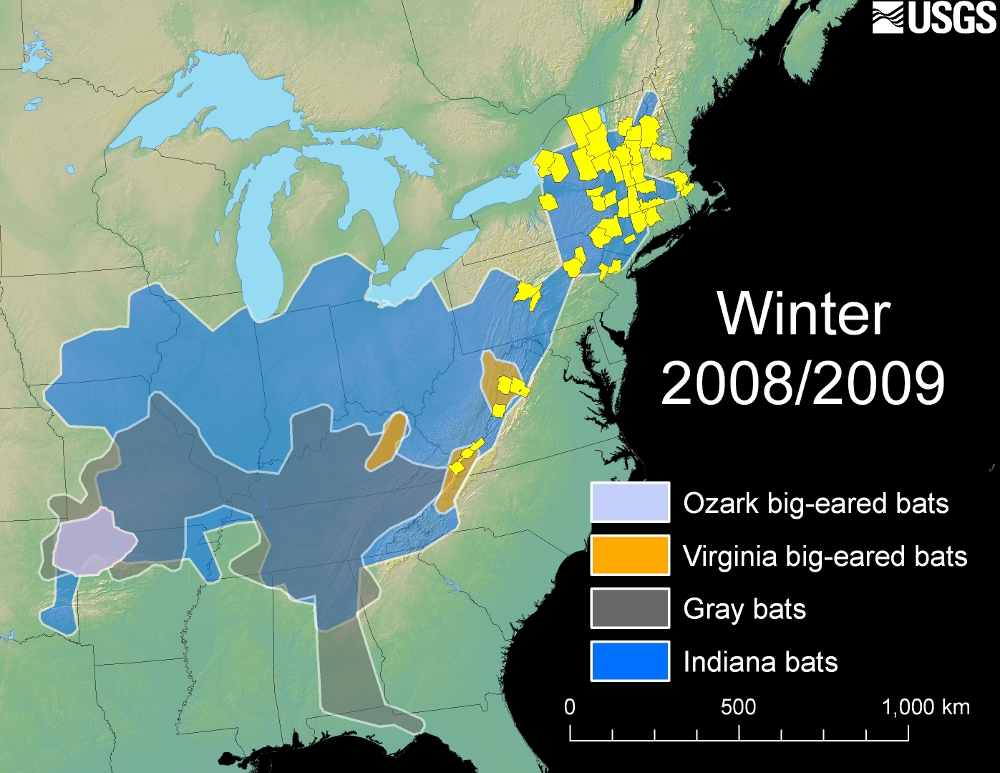

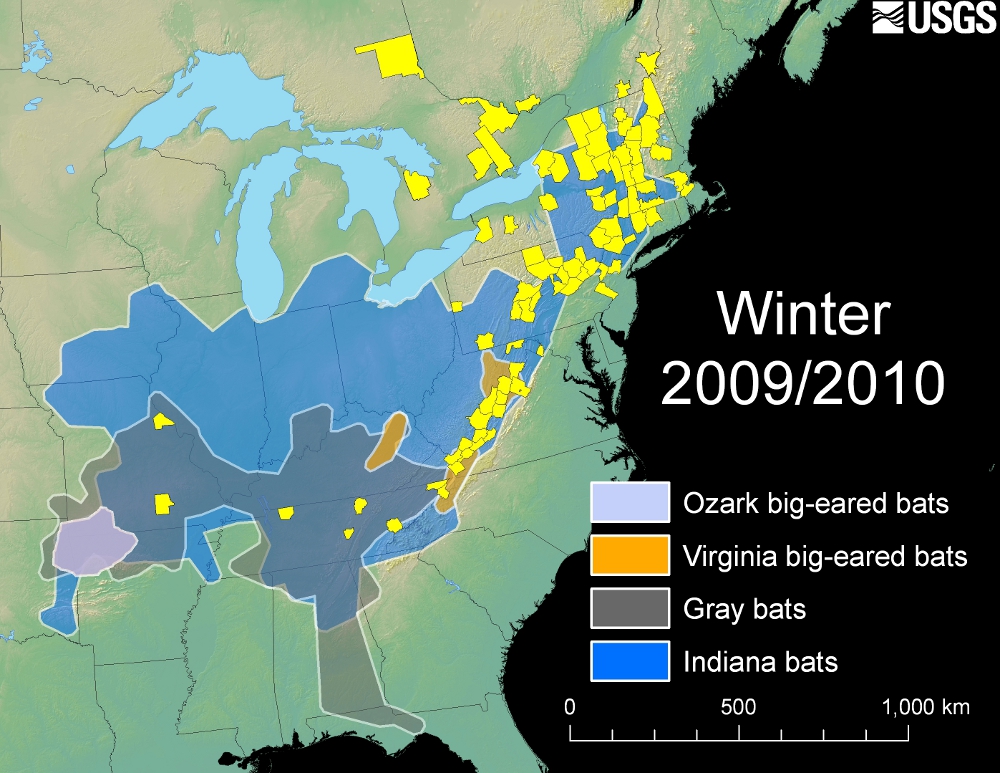

The map below shows the distribution of endangered species of hibernating bats (shaded areas) in relation to the expanding distribution of the fungus (Geomyces destructans) and the disease white-nose syndrome (yellow counties). Endangered species include Ozark big-eared bats (Corynorhinus townsendii ingens), Virginia big-eared bats (C. t. virginianus), Indiana bats (M. sodalis), and gray bats (M. grisescens). For an updated map of sites affected by WNS see http://www.fws.gov/whitenosesyndrome/.

Although the true potential for this fungus to spread is unknown, the possibility of it undermining the ubiquitous survival strategy of bats at higher latitudes has enormous implications. We are just beginning to appreciate the roles that bats play in North American ecosystems, and it is clear that threats like white-nose syndrome have the potential to influence ecosystem function in ways that we currently do not understand.

Since white-nose syndrome emerged during the winter of 2006–2007, a diverse group of scientists, resource managers, and conservation groups have worked diligently to establish its cause. Efforts are now being directed toward developing solutions to the WNS crisis and minimizing its impact on populations of hibernating bats in North America.

USGS scientists at the National Wildlife Health Center and Fort Collins Science Center are supporting the research needs of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal and state agencies as they respond to the developing situation.

Paul Cryan

USGS Fort Collins Science Center

2150 Centre Ave., Bldg. C

Fort Collins, CO 80526-8118

cryanp@usgs.gov

© Photos by Alan Hicks, New York Department of Environmental Conservation