MORGANTOWN, W.Va. (AP) — It stretches nearly 2,200 miles, a ribbon of mountains and meadows, forests and fauna. But scientists, hikers and land managers say the Appalachian Trail is more than a footpath.

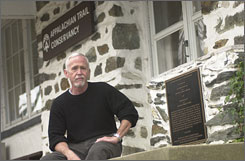

Passing through 14 states and eight national forests from Georgia to Maine — including a 90-mile stretch through Massachusetts — it's also a living laboratory that could help warn 120 million people along the Eastern Seaboard of looming environmental problems. That's why a diverse group of organizations has launched a project to begin long-term monitoring of the environmental health of the trail, with plans to tap into an army of volunteer "citizen scientists" and their professional counterparts. Together, they will collect information about plants and animals, air and water quality, visibility and migration patterns to build an early warning system for the non-hiking public. "It's somewhat like the canary in the coal mine in the sense of using it as a barometer for environmental and human health conditions," says Gregory Miller, president of the Maryland-based American Hiking Society. The Appalachian Mountains are ideal for the project because they are home to one of the richest collections of temperate zone species in the world, and the trail has a natural diversity that is nearly unsurpassed in the national park system. It also has different ecosystems that blend into one another — hardwood forests next to softwood forests next to alpine forests. The idea for the Appalachian Trail Mega-Transect is in its infancy but it already has support from the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service, Cornell University, National Geographic Society and the earth-conscious beauty products company, Aveda Corp. "We're really after two things," says Brian Mitchell, a coordinator with the park service's Northeast Temperate Network in Woodstock, Vt. "We want to get a better understanding of what's happening on the trail so we can better manage it. The other side is we want to take the lessons we learn from the trail and show people that what's happening on the trail does actually affect us." Scientists will periodically issue reports aimed at helping the average American understand the gradual trickle-down effect of environmental problems. High ozone levels, for example, can reduce photosynthesis and growth, and speed up aging and leaf loss in plants. In humans, it can affect the lungs, respiratory tract and eyes, and increase susceptibility to allergens. Atmospheric deposition — airborne sulfur and nitrogen that drop from rain and snow into soil — can affect farming and crop growth. Dave Startzell, executive director of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy in Harpers Ferry, says smog and air quality in the Great Smoky Mountains are good examples of what people need to know. "People will read that on 25 or 30 days in a given year, it's considered unhealthy to walk on the Appalachian Trail, and we think that's going to grab people's attention more than if they just read about air quality trends in general," he said. That's also why volunteers will be critical to the project's success. "It's one thing for people to read about the decline of neotropical migratory bird species or acid deposition or determining air quality and visibility in the abstract. We think it's another thing when people learn about that firsthand by actually helping to collect that information," Startzell says. Environmental change is slow and can be hard to grasp, agrees Mitchell. But people need to look only at rising sea levels to see the potential human impact. "If you have somebody actually going out and seeing where high tide is every year, you can have a measuring point and tell if sea levels are rising," he says. "People don't think that a foot of sea level rise is a big deal — until it's combined with storm surge and a hurricane." The same concepts would apply to the trail, where Mitchell says volunteers could help with such tasks as measuring tree diameters, taking photographs to illustrate visibility, tracking the arrival times of migratory birds and dating the blooming and leaf loss of trees. Mitchell hopes that within the next year, the partners will have at least two flagship programs for volunteers. Advocates of the monitoring plan hope the project will help drive changes in public policy and personal behavior. Earlier this month, United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan lamented "a frightening lack of leadership" in fashioning steps to reduce pollution that scientists believe contributes to global warming. The United States and Australia are the only major industrialized countries to reject the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which requires 35 nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 5% below 1990 levels by 2012. President Bush says it would harm the U.S. economy, and it should have required cutbacks in poorer nations as well. "Part of our hope is that as people become more aware of trends affecting those lands, they'll be motivated to take action," Startzell says, "whether that means switching to a hybrid car or just conducting their own way of life in a little more energy efficient manner, or going to a town hall meeting and advocating for more open space." Miller, of the American Hiking Society, says the trail also could inspire more people to get outdoors and become active at a time when the nation is coping with epidemic levels of childhood obesity and other health problems. "It is both ecologically as well as culturally a ribbon that binds us and connects us," he says. "It reflects the pioneer nature of all our peoples — the connection to the land that maybe some of us have not maintained. "It's something we hope everyone will buy into."

Copyright 2007 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This

material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||