Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center (NOROCK)

Home | About Us | Science | Product Library | News & Events | Staff | Students | Partners | Contact Us

Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center (NOROCK)

Home | About Us | Science | Product Library | News & Events | Staff | Students | Partners | Contact Us

Information Sheet l Overview l Objectives l History l Research & Monitoring l Other Research

The Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST) is an interdisciplinary group of scientists and biologists responsible for long-term monitoring and research efforts on grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). The team is composed of representatives from the U.S. Geological Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, Montana State University, and the states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. This interagency approach ensures consistency in data collection and allows for combining limited resources to address information needs throughout the ecosystem.

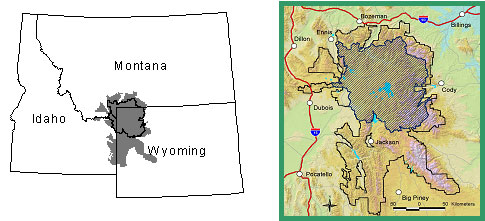

Figure 1. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (left, gray shading). The Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone is defined by the black line on the left and the crosshatched pattern on the right.

A heated debate began in the 1960s and 1970s and grew to a national scope concerning the grizzly bears in the GYE. For decades, grizzly bears were allowed to rummage through garbage dumps searching for food. As early as the 1940s, some researchers suggested closing the open-pit dumps within Yellowstone National Park. In 1963, the Advisory Board on Wildlife Management in the National Parks released the “Leopold Report” which recommended that natural ecosystems should be recreated, including predator/prey relationships.

By 1967, Yellowstone National Park’s Superintendent Anderson began to implement recommendations of the Leopold Report. The Park began closing the open-pit dumps and bears were to be weaned off garbage. Some researchers suggested gradually phasing out the dumps, but the Park staff closed everything, rationalizing that there were enough backcountry bears that did not use dumps to sustain the mortality. The controversy continued because grizzly bear mortality increased substantially as dumps were closed. Between 1967 and 1972, a minimum of 229 Yellowstone ecosystem grizzlies died.

By 1967, Yellowstone National Park’s Superintendent Anderson began to implement recommendations of the Leopold Report. The Park began closing the open-pit dumps and bears were to be weaned off garbage. Some researchers suggested gradually phasing out the dumps, but the Park staff closed everything, rationalizing that there were enough backcountry bears that did not use dumps to sustain the mortality. The controversy continued because grizzly bear mortality increased substantially as dumps were closed. Between 1967 and 1972, a minimum of 229 Yellowstone ecosystem grizzlies died.

The IGBST was formed by the Department of Interior in 1973 as a direct result of this controversy. The high mortality that followed dump closure and concerns for the population’s future led to its listing as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1975. Early research by the team indicated that following listing, the population continued to decline into the 1980s. This information was the foundation and impetus for the formation of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) in 1983. The IGBC, represented by administrators from federal and state agencies, implemented several regulations on federal lands designed to reduce human-caused grizzly bear mortality. These management policies, in concert with favorable environmental conditions, halted the population’s decline. Grizzly bear numbers have increased since the mid-1980s and today bears again occupy historical range well beyond Yellowstone National Park.

We annually monitor the grizzly bear population and ecological components of their habitats in the GYE. Examples include:

Adult females are considered the most important segment of the population and consequently are a major focus of our monitoring effort. Our efforts to document the distribution and abundance of females with cubs within the GYE began in 1973. During the past 6 years (2000-2005) we have counted an average of 42 unique females with cubs of the year in the GYE. Although these counts are not a pure index of bear abundance, when summed over 3 consecutive years (the average reproductive interval for adult females) they approximate a minimum estimate of adult females in the population. These counts and the minimum population estimates derived from them are also used to establish annual quotas for human-caused mortality.

Whitebark pine seeds are arguably the most important fattening food available to grizzly bears during late summer and fall. We annually monitor cone production throughout the GYE on 19 transects. Cone production is highly variable from year to year. Our studies have demonstrated a relationship between cone counts and bear mortality. In years of poor cone production, bear conflicts and deaths increase. Understanding such relationships is useful in predicting and preventing future problems. Ironically, whitebark pine is potentially threatened in the GYE by an introduced fungus, white pine blister rust, which could significantly reduce pine abundance. Blister rust has already decimated whitebark pine in northwest Montana. Infection occurs in the GYE, but as yet has not caused extensive tree mortality.

We began radio-marking bears in 1975. Since then we have monitored over 500 individuals for varying periods. Our trapping and monitoring program changed in 1986 based on directions from the IGBC Population Task Force. They recommended we maintain and monitor a minimum of 15 adult females annually; this target was increased to 25 in 1994. During the past 5 years, we have averaged 25 adult females monitored annually. Data collected from these marked bears provide the information necessary for tracking key population parameters. By observing collared bears, we document age of first reproduction, average litter size, how often a female produces a litter, and causes of mortality. These data allow us to estimate survival among different sex and age classes of bears. This information is used in conjunction with other estimates (i.e. unduplicated females) to assess population trend and help focus management activities toward issues that impact bears.

We began radio-marking bears in 1975. Since then we have monitored over 500 individuals for varying periods. Our trapping and monitoring program changed in 1986 based on directions from the IGBC Population Task Force. They recommended we maintain and monitor a minimum of 15 adult females annually; this target was increased to 25 in 1994. During the past 5 years, we have averaged 25 adult females monitored annually. Data collected from these marked bears provide the information necessary for tracking key population parameters. By observing collared bears, we document age of first reproduction, average litter size, how often a female produces a litter, and causes of mortality. These data allow us to estimate survival among different sex and age classes of bears. This information is used in conjunction with other estimates (i.e. unduplicated females) to assess population trend and help focus management activities toward issues that impact bears.

Identifying the locations and causes of grizzly bear mortality is another key component in understanding the dynamics of this population. Over 80% of all documented bear mortality is human-caused. Tracking human-caused bear deaths helps define patterns and trends that can direct management programs designed to reduce bear mortality.

Contact:

Mark Haroldson

Phone: 406-994-5042

Fax: 406-994-6416

Email: mark_haroldson@usgs.gov