Dr. Victoria Cargill talks to students about HIV and AIDS at the opening of a National Library of Medicine exhibition entitled, "Against the Odds: Making a Difference in Global Health."

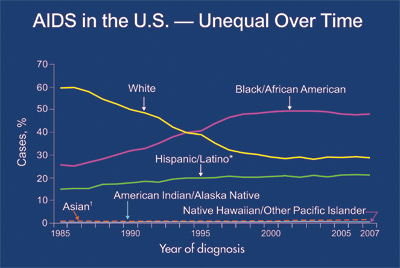

In the United States, the groups that AIDS affects have changed since the beginning of the epidemic. The percentage of new AIDS cases among whites has decreased, but the percentages among African Americans and Hispanics have increased, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (See interview with Dr. Anthony Fauci, starting on page 11.)

"There is a grossly disproportionate impact of the epidemic upon those who are already marginalized—the poor, the disenfranchised, and racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities," says Victoria Cargill, M.D., M.S.C.E., Director of Clinical Studies and Director of Minority Research at the NIH Office of AIDS Research (OAR).

Of adults and adolescents diagnosed with AIDS during 2007 (the most recent CDC data):

- 48% were black

- 28% were white

- 21% were Hispanic

- 1% were Asian

- Less than 1% each was Native American/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander.

- In 2007, an estimated 26,111 AIDS cases were diagnosed in U.S. minority races and ethnicities. That accounted for 71 percent of all AIDS cases diagnosed that year in the U.S.

"The HIV epidemic in many of our cities has rates of infection that rival some third-world nations," says Dr. Cargill. "We need only look at Washington, D.C., to see that. Sadly, while it may have some of the worst numbers, it is not alone."

In addition to her NIH work, Dr. Cargill sees the challenges first-hand at a clinic she runs in the District of Columbia. In addition to being HIV-positive, patients are often fighting other health challenges, as well as cultural and economic hardships. "Many of our patients are obese, HIV-infected, and have developed diabetes," she says.

These other issues make the HIV challenges even harder. Dr. Cargill encourages her patients to work with her and to be partners in recovering their own health. She is now starting an incentives program that she hopes will give her patients the tools they need to change their behaviors and live healthier lives.

"There is a clear gap between knowledge and behavior," she adds, "and when survival is added to the equation, that widens the gap. The exchange of sex for money, drugs, shelter, and safety is not a new transaction. HIV infection has just made the transaction more fraught with danger—and fatality."

HIV: Getting Tested Is the First Step

"Being tested for HIV infection is so important, but it isn't the end of the line," says Dr. Cargill. "It is just the beginning of the journey."

Once a person is tested for HIV, there is an immediate fork in the road, she adds. "You're either HIV-infected (tested positive) or HIV-uninfected (tested negative). Both groups need our attention," she says. "If the person tests positive, there is a critical need to not only engage the person in medical care, but to also get them to examine their social and sexual networks to look for other infections. They also need to start making behavior changes that are a central part of treatment, reducing transmission risk to others, and remaining an active participant in HIV care.

"If the person is HIV-negative, then it's critical to review the behaviors that might place him or her at risk. You have to go beyond that and explore the thinking that allows people to conclude that an HIV-negative result means whatever they have been doing up to that point is OK. That's false. It just may mean that they have not encountered an HIV infected partner yet."

For those at high risk of HIV infection, testing must be paired with behavior changes that take them out of the high-risk category, emphasizes Dr. Cargill.

Photo: iStock

HIV and Pregnancy

Are there ways to help HIV-infected women keep from passing HIV to their newborns? The answer is usually yes.

Today, HIV-infected women receive a combination of highly active AIDS drugs throughout pregnancy. HIV infection of newborns has shrunk to less than 2 percent of births by HIV-positive women in the United States. This is done through a combination of drug therapy, universal prenatal HIV counseling and testing, cesarean delivery, and avoidance of breastfeeding.

"We now have a series of guidelines to prevent the perinatal (around the time of birth) transmission of HIV infection, and a sizable number of agents to prevent HIV transmission—not just relying on a single agent," says Dr. Victoria Cargill of the NIH Office of AIDS Research.