For more information, visit http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/hvd/

What Is Heart Valve Disease?

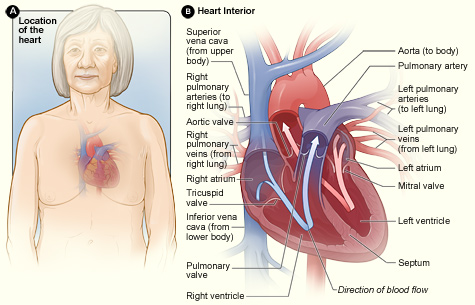

Heart valve disease occurs if one or more of your heart valves don't work well. The heart has four valves: the tricuspid (tri-CUSS-pid), pulmonary (PULL-mun-ary), mitral (MI-trul), and aortic (ay-OR-tik) valves.

These valves have tissue flaps that open and close with each heartbeat. The flaps make sure blood flows in the right direction through your heart's four chambers and to the rest of your body.

Healthy Heart Cross-Section

Figure A shows the location of the heart in the body. Figure B shows a cross-section of a healthy heart and its inside structures. The blue arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-poor blood flows through the heart to the lungs. The red arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-rich blood flows from the lungs into the heart and then out to the body.

Birth defects, age-related changes, infections, or other conditions can cause one or more of your heart valves to not open fully or to let blood leak back into the heart chambers. This can make your heart work harder and affect its ability to pump blood.

Overview

How the Heart Valves Work

At the start of each heartbeat, blood returning from the body and lungs fills the atria (the heart's two upper chambers). The mitral and tricuspid valves are located at the bottom of these chambers. As the blood builds up in the atria, these valves open to allow blood to flow into the ventricles (the heart's two lower chambers).

After a brief delay, as the ventricles begin to contract, the mitral and tricuspid valves shut tightly. This prevents blood from flowing back into the atria.

As the ventricles contract, they pump blood through the pulmonary and aortic valves. The pulmonary valve opens to allow blood to flow from the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery. This artery carries blood to the lungs to get oxygen.

At the same time, the aortic valve opens to allow blood to flow from the left ventricle into the aorta. The aorta carries oxygen-rich blood to the body. As the ventricles relax, the pulmonary and aortic valves shut tightly. This prevents blood from flowing back into the ventricles.

For more information about how the heart pumps blood and detailed animations, go to the Health Topics How the Heart Works article.

Heart Valve Problems

Heart valves can have three basic kinds of problems: regurgitation (re-GUR-jih-TA-shun), stenosis (ste-NO-sis), and atresia (a-TRE-ze-ah).

Regurgitation, or backflow, occurs if a valve doesn't close tightly. Blood leaks back into the chambers rather than flowing forward through the heart or into an artery.

In the United States, backflow most often is due to prolapse. "Prolapse" is when the flaps of the valve flop or bulge back into an upper heart chamber during a heartbeat. Prolapse mainly affects the mitral valve.

Stenosis occurs if the flaps of a valve thicken, stiffen, or fuse together. This prevents the heart valve from fully opening. As a result, not enough blood flows through the valve. Some valves can have both stenosis and backflow problems.

Atresia occurs if a heart valve lacks an opening for blood to pass through.

Some people are born with heart valve disease, while others acquire it later in life. Heart valve disease that develops before birth is called congenital (kon-JEN-ih-tal) heart valve disease. Congenital heart valve disease can occur alone or with other congenital heart defects.

Congenital heart valve disease often involves pulmonary or aortic valves that don't form properly. These valves may not have enough tissue flaps, they may be the wrong size or shape, or they may lack an opening through which blood can flow properly.

Acquired heart valve disease usually involves aortic or mitral valves. Although the valves are normal at first, problems develop over time.

Both congenital and acquired heart valve disease can cause stenosis or backflow.

Outlook

Many people have heart valve defects or disease but don't have symptoms. For some people, the condition mostly stays the same throughout their lives and doesn't cause any problems.

For other people, heart valve disease slowly worsens until symptoms develop. If not treated, advanced heart valve disease can cause heart failure, stroke, blood clots, or death due to sudden cardiac arrest (SCA).

Currently, no medicines can cure heart valve disease. However, lifestyle changes and medicines can relieve many of its symptoms and complications.

These treatments also can lower your risk of developing a life-threatening condition, such as stroke or SCA. Eventually, you may need to have your faulty heart valve repaired or replaced.

Some types of congenital heart valve disease are so severe that the valve is repaired or replaced during infancy, childhood, or even before birth. Other types may not cause problems until middle-age or older, if at all.

Other Names for Heart Valve Disease

- Aortic regurgitation

- Aortic stenosis

- Aortic sclerosis

- Aortic valve disease

- Bicuspid aortic valve

- Congenital heart defect

- Congenital valve disease

- Mitral regurgitation

- Mitral stenosis

- Mitral valve disease

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Pulmonic regurgitation

- Pulmonic stenosis

- Pulmonic valve disease

- Tricuspid regurgitation

- Tricuspid stenosis

- Tricuspid valve disease

What Causes Heart Valve Disease?

Heart conditions and other disorders, age-related changes, rheumatic fever, or infections can cause acquired heart valve disease. These factors change the shape or flexibility of once-normal valves.

The cause of congenital heart valve disease isn't known. It occurs before birth as the heart is forming. Congenital heart valve disease can occur alone or with other types of congenital heart defects.

Heart Conditions and Other Disorders

Certain conditions can stretch and distort the heart valves, such as:

- Damage and scar tissue due to a heart attack or injury to the heart.

- Advanced high blood pressure and heart failure. These conditions can enlarge the heart or the main arteries.

- Atherosclerosis (ath-er-o-skler-O-sis) in the aorta. Atherosclerosis is a condition in which a waxy substance called plaque (plak) builds up inside the arteries. The aorta is the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood to the body.

Age-Related Changes

Men older than 65 and women older than 75 are prone to developing calcium and other types of deposits on their heart valves. These deposits stiffen and thicken the valve flaps and limit blood flow through the valve (stenosis).

The aortic valve is especially prone to this problem. The deposits look similar to the plaque deposits seen in people who have atherosclerosis. Some of the same processes may cause both atherosclerosis and heart valve disease.

Rheumatic Fever

Untreated strep throat or other infections with strep bacteria that progress to rheumatic fever can cause heart valve disease.

When the body tries to fight the strep infection, one or more heart valves may be damaged or scarred in the process. The aortic and mitral valves most often are affected. Symptoms of heart valve damage often don't appear until many years after recovery from rheumatic fever.

Today, most people who have strep infections are treated with antibiotics before rheumatic fever occurs. If you have strep throat, take all of the antibiotics your doctor prescribes, even if you feel better before the medicine is gone.

Heart valve disease caused by rheumatic fever mainly affects older adults who had strep infections before antibiotics were available. It also affects people from developing countries, where rheumatic fever is more common.

Infections

Common germs that enter the bloodstream and get carried to the heart can sometimes infect the inner surface of the heart, including the heart valves. This rare but serious infection is called infective endocarditis (EN-do-kar-DI-tis), or IE.

The germs can enter the bloodstream through needles, syringes, or other medical devices and through breaks in the skin or gums. Often, the body's defenses fight off the germs and no infection occurs. Sometimes these defenses fail, which leads to IE.

IE can develop in people who already have abnormal blood flow through a heart valve as the result of congenital or acquired heart valve disease. The abnormal blood flow causes blood clots to form on the surface of the valve. The blood clots make it easier for germs to attach to and infect the valve.

IE can worsen existing heart valve disease.

Other Conditions and Factors Linked To Heart Valve Disease

Many other conditions and factors are linked to heart valve disease. However, the role they play in causing heart valve disease often isn't clear.

- Autoimmune disorders. Autoimmune disorders, such as lupus, can affect the aortic and mitral valves.

- Carcinoid syndrome. Tumors in the digestive tract that spread to the liver or lymph nodes can affect the tricuspid and pulmonary valves.

- Metabolic disorders. Relatively uncommon diseases (such as Fabry disease) and other metabolic disorders (such as high blood cholesterol) can affect the heart valves.

- Diet medicines. The use of fenfluramine and phentermine ("fen-phen") has sometimes been linked to heart valve problems. These problems typically stabilize or improve after the medicine is stopped.

- Radiation therapy. Radiation therapy to the chest area can cause heart valve disease. This therapy is used to treat cancer. Heart valve disease due to radiation therapy may not cause symptoms until years after the therapy.

- Marfan syndrome. Congenital disorders, such as Marfan syndrome and other connective tissue disorders, can affect the heart valves.

Who Is at Risk for Heart Valve Disease?

Older age is a risk factor for heart valve disease. As you age, your heart valves thicken and become stiffer. Also, people are living longer now than in the past. As a result, heart valve disease has become an increasing problem.

People who have a history of infective endocarditis (IE), rheumatic fever, heart attack, or heart failure—or previous heart valve disease—also are at higher risk for heart valve disease. In addition, having risk factors for IE, such as intravenous drug use, increases the risk of heart valve disease.

You're also at higher risk for heart valve disease if you have risk factors for coronary heart disease. These risk factors include high blood cholesterol, high blood pressure, smoking, insulin resistance, diabetes, overweight or obesity, lack of physical activity, and a family history of early heart disease.

Some people are born with an aortic valve that has two flaps instead of three. Sometimes an aortic valve may have three flaps, but two flaps are fused together and act as one flap. This is called a bicuspid or bicommissural aortic valve. People who have this congenital condition are more likely to develop aortic heart valve disease.

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Heart Valve Disease?

Major Signs and Symptoms

The main sign of heart valve disease is an unusual heartbeat sound called a heart murmur. Your doctor can hear a heart murmur with a stethoscope.

However, many people have heart murmurs without having heart valve disease or any other heart problems. Others may have heart murmurs due to heart valve disease, but have no other signs or symptoms.

Heart valve disease often worsens over time, so signs and symptoms may occur years after a heart murmur is first heard. Many people who have heart valve disease don't have any symptoms until they're middle-aged or older.

Other common signs and symptoms of heart valve disease relate to heart failure, which heart valve disease can cause. These signs and symptoms include:

- Unusual fatigue (tiredness)

- Shortness of breath, especially when you exert yourself or when you're lying down

- Swelling in your ankles, feet, legs, abdomen, and veins in the neck

Other Signs and Symptoms

Heart valve disease can cause chest pain that may happen only when you exert yourself. You also may notice a fluttering, racing, or irregular heartbeat. Some types of heart valve disease, such as aortic or mitral valve stenosis, can cause dizziness or fainting.

How Is Heart Valve Disease Diagnosed?

Your primary care doctor may detect a heart murmur or other signs of heart valve disease. However, a cardiologist usually will diagnose the condition. A cardiologist is a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating heart problems.

To diagnose heart valve disease, your doctor will ask about your signs and symptoms. He or she also will do a physical exam and look at the results from tests and procedures.

Physical Exam

Your doctor will listen to your heart with a stethoscope. He or she will want to find out whether you have a heart murmur that's likely caused by a heart valve problem.

Your doctor also will listen to your lungs as you breathe to check for fluid buildup. He or she will check for swollen ankles and other signs that your body is retaining water.

Tests and Procedures

Echocardiography (echo) is the main test for diagnosing heart valve disease. But an EKG (electrocardiogram) or chest x ray commonly is used to reveal certain signs of the condition. If these signs are present, echo usually is done to confirm the diagnosis.

Your doctor also may recommend other tests and procedures if you're diagnosed with heart valve disease. For example, you may have cardiac catheterization, (KATH-eh-ter-ih-ZA-shun), stress testing, or cardiac MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). These tests and procedures help your doctor assess how severe your condition is so he or she can plan your treatment.

EKG

This simple test detects and records the heart's electrical activity. An EKG can detect an irregular heartbeat and signs of a previous heart attack. It also can show whether your heart chambers are enlarged.

An EKG usually is done in a doctor's office.

Chest X Ray

This test can show whether certain sections of your heart are enlarged, whether you have fluid in your lungs, or whether calcium deposits are present in your heart.

A chest x ray helps your doctor learn which type of valve defect you have, how severe it is, and whether you have any other heart problems.

Echocardiography

Echo uses sound waves to create a moving picture of your heart as it beats. A device called a transducer is placed on the surface of your chest.

The transducer sends sound waves through your chest wall to your heart. Echoes from the sound waves are converted into pictures of your heart on a computer screen.

Echo can show:

- The size and shape of your heart valves and chambers

- How well your heart is pumping blood

- Whether a valve is narrow or has backflow

Your doctor may recommend transesophageal (tranz-ih-sof-uh-JEE-ul) echo, or TEE, to get a better image of your heart.

During TEE, the transducer is attached to the end of a flexible tube. The tube is guided down your throat and into your esophagus (the passage leading from your mouth to your stomach). From there, your doctor can get detailed pictures of your heart.

You'll likely be given medicine to help you relax during this procedure.

Cardiac Catheterization

For this procedure, a long, thin, flexible tube called a catheter is put into a blood vessel in your arm, groin (upper thigh), or neck and threaded to your heart. Your doctor uses x-ray images to guide the catheter.

Through the catheter, your doctor does diagnostic tests and imaging that show whether backflow is occurring through a valve and how fully the valve opens. You'll be given medicine to help you relax, but you will be awake during the procedure.

Your doctor may recommend cardiac catheterization if your signs and symptoms of heart valve disease aren't in line with your echo results.

The procedure also can help your doctor assess whether your symptoms are due to specific valve problems or coronary heart disease. All of this information helps your doctor decide the best way to treat you.

Stress Test

During stress testing, you exercise to make your heart work hard and beat fast while heart tests and imaging are done. If you can't exercise, you may be given medicine to raise your heart rate.

A stress test can show whether you have signs and symptoms of heart valve disease when your heart is working hard. It can help your doctor assess the severity of your heart valve disease.

Cardiac MRI

Cardiac MRI uses a powerful magnet and radio waves to make detailed images of your heart. A cardiac MRI image can confirm information about valve defects or provide more detailed information.

This information can help your doctor plan your treatment. An MRI also may be done before heart valve surgery to help your surgeon plan for the surgery.

How Is Heart Valve Disease Treated?

Currently, no medicines can cure heart valve disease. However, lifestyle changes and medicines often can successfully treat symptoms and delay problems for many years. Eventually, though, you may need surgery to repair or replace a faulty heart valve.

The goals of treating heart valve disease might include:

- Preventing, treating, or relieving the symptoms of other related heart conditions.

- Protecting heart valves from further damage.

- Repairing or replacing faulty valves when they cause severe symptoms or become life threatening. Replacement valves can be man-made or biological.

Preventing, Treating, or Relieving the Symptoms of Other Related Heart Conditions

To relieve the symptoms of heart conditions related to heart valve disease, your doctor may advise you to quit smoking and follow a healthy diet.

A healthy diet includes a variety of vegetables and fruits. It also includes whole grains, fat-free or low-fat dairy products, and protein foods, such as lean meats, poultry without skin, seafood, processed soy products, nuts, seeds, beans, and peas.

A healthy diet is low in sodium (salt), added sugars, solid fats, and refined grains. Solid fats are saturated fat and trans fatty acids. Refined grains come from processing whole grains, which results in a loss of nutrients (such as dietary fiber).

For more information about following a healthy diet, go to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's "Your Guide to Lowering Your Blood Pressure With DASH" and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's ChooseMyPlate.gov Web site. Both resources provide general information about healthy eating.

Your doctor may ask you to limit physical activities that make you short of breath and tired. He or she also may ask that you limit competitive athletic activity, even if the activity doesn't leave you unusually short of breath or tired.

Your doctor may prescribe medicines to:

- Treat heart failure. Heart failure medicines widen blood vessels and rid the body of excess fluid.

- Lower high blood pressure or high blood cholesterol.

- Treat coronary heart disease (CHD). CHD medicines can reduce your heart's workload and relieve symptoms.

- Prevent arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats).

- Thin the blood and prevent clots (if you have a man-made replacement valve). These medicines also are prescribed for mitral stenosis or other valve defects that raise the risk of blood clots.

Protecting Heart Valves From Further Damage

If you've had previous heart valve disease and now have a man-made valve, you may be at risk for a heart infection called infective endocarditis (IE). This infection can worsen your heart valve disease.

One of the most common causes of IE is poor dental hygiene. To prevent this serious infection, floss and brush your teeth and regularly see a dentist. Gum infections and tooth decay can increase the risk of IE.

Let your doctors and dentists know if you have a man-made valve or if you've had IE before. They may give you antibiotics before dental procedures (such as dental cleanings) that could allow bacteria to enter your bloodstream. Talk to your doctor about whether you need to take antibiotics before such procedures.

Repairing or Replacing Heart Valves

Your doctor may recommend repairing or replacing your heart valve(s), even if your heart valve disease isn't causing symptoms. Repairing or replacing a valve can prevent lasting damage to your heart and sudden death.

Having heart valve repair or replacement depends on many factors, including:

- The severity of your valve disease.

- Your age and general health.

- Whether you need heart surgery for other conditions, such as bypass surgery to treat CHD. Bypass surgery and valve surgery can be done at the same time.

When possible, heart valve repair is preferred over heart valve replacement. Valve repair preserves the strength and function of the heart muscle. People who have valve repair also have a lower risk of IE after the surgery, and they don't need to take blood-thinning medicines for the rest of their lives.

However, heart valve repair surgery is harder to do than valve replacement. Also, not all valves can be repaired. Mitral valves often can be repaired. Aortic and pulmonary valves often have to be replaced.

Repairing Heart Valves

Heart surgeons can repair heart valves by:

- Separating fused valve flaps

- Removing or reshaping tissue so the valve can close tighter

- Adding tissue to patch holes or tears or to increase the support at the base of the valve

Sometimes cardiologists repair heart valves using cardiac catheterization. Although catheter procedures are less invasive than surgery, they may not work as well for some patients.

Work with your doctor to decide whether repair is appropriate. If so, your doctor can advise you on the best procedure for doing it.

Balloon valvuloplasty. Heart valves that don't fully open (stenosis) can be repaired with surgery or with a less invasive catheter procedure called balloon valvuloplasty (VAL-vyu-lo-plas-tee). This procedure also is called balloon valvotomy (val-VOT-o-me).

During the procedure, a catheter (thin tube) with a balloon at its tip is threaded through a blood vessel to the faulty valve in your heart. The balloon is inflated to help widen the opening of the valve. Your doctor then deflates the balloon and removes both it and the tube.

You're awake during the procedure, which usually requires an overnight stay in a hospital.

Balloon valvuloplasty relieves many of the symptoms of heart valve disease, but it may not cure it. The condition can worsen over time. You still may need medicines to treat symptoms or surgery to repair or replace the faulty valve.

Balloon valvuloplasty has a shorter recovery time than surgery. The procedure may work as well as surgery for some patients who have mitral valve stenosis. Thus, for these people, balloon valvuloplasty often is preferred over surgical repair or replacement.

Balloon valvuloplasty doesn't work as well as surgery for adults who have aortic valve stenosis.

Doctors often use balloon valvuloplasty to repair valve stenosis in infants and children.

Replacing Heart Valves

Sometimes heart valves can't be repaired and must be replaced. This surgery involves removing the faulty valve and replacing it with a man-made or biological valve.

Biological valves are made from pig, cow, or human heart tissue and may have man-made parts as well. These valves are specially treated, so you won't need medicines to stop your body from rejecting the valve.

Man-made valves last longer than biological valves and usually don't have to be replaced. Biological valves usually have to be replaced after about 10 years, although newer ones may last 15 years or longer.

Unlike biological valves, however, man-made valves require you to take blood-thinning medicines for the rest of your life. These medicines prevent blood clots from forming on the valve. Blood clots can cause a heart attack or stroke. Man-made valves also raise your risk of IE.

You and your doctor will decide together whether you should have a man-made or biological replacement valve.

If you're a woman of childbearing age or if you're athletic, you may prefer a biological valve so you don't have to take blood-thinning medicines. If you're elderly, you also may prefer a biological valve, as it will likely last for the rest of your life.

Other Approaches for Repairing and Replacing Heart Valves

Some newer forms of heart valve repair and replacement surgery are less invasive than traditional surgery. These procedures use smaller incisions (cuts) to reach the heart valves. Hospital stays for these newer types of surgery usually are 3–5 days, compared with 5-day stays for traditional heart valve surgery.

New surgeries tend to cause less pain and have a lower risk of infection. Recovery time also tends to be shorter—2–4 weeks versus 6–8 weeks for traditional surgery.

Some cardiologists and surgeons are exploring catheter procedures that involve threading clips or other devices through blood vessels to faulty heart valves. The clips or devices are used to reshape the valves and stop the backflow of blood.

People who receive these clips recover more easily than people who have surgery. However, the clips may not treat backflow as well as surgery. Researchers are still studying this treatment method.

Doctor also may use catheters to replace faulty aortic valves. This procedure is called transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).

For this procedure, the catheter usually is inserted into an artery in the groin (upper thigh) and threaded to the heart. At the end of the catheter is a deflated balloon with a folded replacement valve around it.

Once the replacement valve is properly placed, the balloon is used to expand the new valve so it fits securely within the old valve. The balloon is then deflated, and the balloon and catheter are removed.

A replacement valve also can be inserted in an existing replacement valve that is failing. This is called a valve-in-valve procedure.

Catheter procedures may be an option for patients who have conditions that make open-heart surgery too risky. Only a few medical centers have experience with these fairly new procedures.

Doctors also treat faulty aortic valves with a procedure called the Ross operation. During this operation, your doctor removes your faulty aortic valve and replaces it with your pulmonary valve. Your pulmonary valve is then replaced with a pulmonary valve from a deceased human donor.

This is more involved surgery than typical valve replacement, and it has a greater risk of complications.

The Ross operation may be especially useful for children because the surgically replaced valves continue to grow with the child. Also, lifelong treatment with blood-thinning medicines isn't required.

But in some patients, one or both valves fail to work well within a few years of the surgery. Experts continue to debate and study the usefulness of this procedure.

Serious risks from all types of heart valve surgery vary according to your age, health, the type of valve defect(s) you have, and the surgical procedures used.

How Can Heart Valve Disease Be Prevented?

To prevent heart valve disease caused by rheumatic fever, see your doctor if you have signs of a strep infection. These signs include a painful sore throat, fever, and white spots on your tonsils.

If you do have a strep infection, be sure to take all medicines prescribed to treat it. Prompt treatment of strep infections can prevent rheumatic fever, which damages the heart valves.

It's possible that exercise, a healthy diet, and medicines that lower cholesterol might prevent aortic stenosis (thickening and stiffening of the aortic valve). Researchers continue to study this possibility.

A healthy diet, physical activity, other lifestyle changes, and medicines aimed at preventing a heart attack, high blood pressure, or heart failure also may help prevent heart valve disease.

If you've had previous heart valve disease and now have a man-made valve, you're at risk for a heart infection called infective endocarditis (IE).

One of the most common causes of IE is poor dental hygiene. Thus, to prevent this serious infection, floss and brush your teeth and regularly see a dentist. Gum infections and tooth decay can increase the risk of IE.

Let your doctors and dentists know if you have a man-made valve or if you've had IE before. They may give you antibiotics before dental procedures (such as dental cleanings) that could allow bacteria to enter your bloodstream. Talk to your doctor about whether you need to take antibiotics before such procedures.

Living With Heart Valve Disease

Heart valve disease is a lifelong condition. However, many people have heart valve defects or disease but don't have symptoms. For some people, the condition mostly stays the same throughout their lives and doesn't cause any problems.

For other people, the condition slowly worsens until symptoms develop. If not treated, advanced heart valve disease can cause heart failure or other life-threatening conditions.

Eventually, you may need to have your faulty heart valve(s) repaired or replaced. After repair or replacement, you'll still need certain medicines and regular checkups with your doctor.

Ongoing Care

If you have heart valve disease, see your doctor regularly for checkups and for echocardiography or other tests. This will allow your doctor to check the progress of your heart valve disease.

Call your doctor if your symptoms worsen or you have new symptoms. Also, discuss with your doctor whether lifestyle changes might benefit you. Ask him or her which types of physical activity are safe for you.

Call your doctor if you have symptoms of infective endocarditis (IE). Symptoms of this heart infection include fever, chills, muscle aches, night sweats, problems breathing, fatigue (tiredness), weakness, red spots on the palms and soles, and swelling of the feet, legs, and belly.

Let your doctors and dentists know if you have a man-made valve or if you've had IE before. They may give you antibiotics before dental procedures (such as dental cleanings) that could allow bacteria to enter your bloodstream. Talk to your doctor about whether you need to take antibiotics before such procedures.

Take all of your medicines as prescribed.

Pregnancy and Heart Valve Disease

Mild or moderate heart valve disease during pregnancy usually can be managed with medicines or bed rest. With proper care, the disease usually won't pose heightened risks to the mother or fetus.

Doctors can treat most heart valve conditions with medicines that are safe to take during pregnancy. Your doctor can advise you on which medicines are safe for you.

Severe heart valve disease can make pregnancy or labor and delivery risky. If you have severe heart valve disease, consider having your heart valves repaired or replaced before getting pregnant. This treatment also can be done during pregnancy, if needed. However, this surgery poses danger to both the mother and fetus.

Clinical Trials

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) is strongly committed to supporting research aimed at preventing and treating heart, lung, and blood diseases and conditions and sleep disorders.

NHLBI-supported research has led to many advances in medical knowledge and care. For example, this research has uncovered some of the causes of heart diseases and conditions, as well as ways to prevent or treat them.

Many more questions remain about heart diseases and conditions, including heart valve disease. Thus, the NHLBI continues to support research to learn more. For example, NHLBI-supported research on heart valve disease includes studies that explore:

- New techniques to evaluate mitral valve backflow

- Whether mitral valve repair or replacement works better for people who have severe backflow through their mitral valves

- Whether coronary artery bypass grafting alone or with mitral valve repair works better for treating people who have moderate mitral valve backflow and coronary heart disease

Much of this research depends on the willingness of volunteers to take part in clinical trials. Clinical trials test new ways to prevent, diagnose, or treat various diseases and conditions.

For example, new treatments for a disease or condition (such as medicines, medical devices, surgeries, or procedures) are tested in volunteers who have the illness. Testing shows whether a treatment is safe and effective in humans before it is made available for widespread use.

By taking part in a clinical trial, you can gain access to new treatments before they're widely available. You also will have the support of a team of health care providers, who will likely monitor your health closely. Even if you don't directly benefit from the results of a clinical trial, the information gathered can help others and add to scientific knowledge.

If you volunteer for a clinical trial, the research will be explained to you in detail. You'll learn about treatments and tests you may receive, and the benefits and risks they may pose. You'll also be given a chance to ask questions about the research. This process is called informed consent.

If you agree to take part in the trial, you'll be asked to sign an informed consent form. This form is not a contract. You have the right to withdraw from a study at any time, for any reason. Also, you have the right to learn about new risks or findings that emerge during the trial.

For more information about clinical trials related to heart valve disease, talk with your doctor. You also can visit the following Web sites to learn more about clinical research and to search for clinical trials:

- http://clinicalresearch.nih.gov

- www.clinicaltrials.gov

- www.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/index.htm

- www.researchmatch.org

For more information about clinical trials for children, visit the NHLBI's Children and Clinical Studies Web page.

Links to Other Information About Heart Valve Disease

NHLBI Resources

- Congenital Heart Defects (Health Topics)

- Endocarditis (Health Topics)

- Heart Murmur (Health Topics)

- Heart Surgery (Health Topics)

- Mitral Valve Prolapse (Health Topics)

- "Your Guide to Living Well With Heart Disease"

Non-NHLBI Resources

- Endocarditis (MedlinePlus)

- Heart Valve Disease (MedlinePlus)

- Heart Valve Surgery (MedlinePlus)

Clinical Trials

- Children and Clinical Studies

- Clinical Trials (Health Topics)

- Current Research (ClinicalTrials.gov)

- NHLBI Clinical Trials

- NIH Clinical Research Trials and You (National Institutes of Health)

- Pediatric Cardiac Genomic Consortium (NHLBI)

- Pediatric Heart Network (NHLBI)

- ResearchMatch (funded by the National Institutes of Health)