It’s one of the pressing questions of cancer research: Does screening reduce mortality? In 1993, the National Cancer Institute launched one of the largest cancer screening trials ever planned in the United States, in an effort to answer the question of screening efficacy in four cancers: prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian. Ten centers across the country ultimately accrued more than 150,000 men and women in a study that “mimicked how people actually get tested—by looking at their overall health and then getting screened for a number of cancers —to see whether these techniques worked in detecting cancers early and lowering chances of death, when compared to the entire range of options patients are presented by community physicians” said Christine Berg, M.D., chief of NCI’s Early Detection Research Group and project officer for the Prostate Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian (PLCO) screening trial. Nineteen years after it began, PLCO has now released the trial’s last major outcome finding, for colorectal cancer.

It’s one of the pressing questions of cancer research: Does screening reduce mortality? In 1993, the National Cancer Institute launched one of the largest cancer screening trials ever planned in the United States, in an effort to answer the question of screening efficacy in four cancers: prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian. Ten centers across the country ultimately accrued more than 150,000 men and women in a study that “mimicked how people actually get tested—by looking at their overall health and then getting screened for a number of cancers —to see whether these techniques worked in detecting cancers early and lowering chances of death, when compared to the entire range of options patients are presented by community physicians” said Christine Berg, M.D., chief of NCI’s Early Detection Research Group and project officer for the Prostate Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian (PLCO) screening trial. Nineteen years after it began, PLCO has now released the trial’s last major outcome finding, for colorectal cancer.

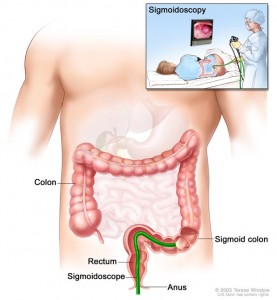

The investigators found that, overall, colorectal cancer mortality was reduced by 26 percent and incidence was reduced by 21 percent as a result of screening with flexible sigmoidoscopy. In absolute terms, this translates three fewer colorectal cancers, and one less death from colorectal cancer, per 1,000 people screened, over a 10 year period. This technique has fewer side effects, requires less bowel preparation, and has a lower risk of bowel perforation (when the screening instrument pokes a hole in the intestine) than colonoscopy.

“This study shows that an invasive procedure used as a first line of screening can be beneficial,” said Berg.

The history of the PLCO trial is a reminder, as well, of the time and commitment it often takes to obtain important information about cancer screening, detection, and treatment. It is the kind of study that few organizations other than NCI could have helped to organize.

NCI chose PLCO sites based on their ability to recruit, screen, and follow up participants. The centers were distributed across the U.S. so that the trial population represented a wide a range as possible of ethnicities and communities. “To really get answers to the questions posed by this trial, it was imperative that the number of participants was high,” said Berg.

The Ten PLCO screening centers:

|

About 78,000 women and 77,000 men were enrolled in the trial. Of those, 39,105 women and 38,340 men were randomized to the intervention arm of the study, where the men received screening for prostate, lung, and colorectal cancers during their first six years and follow-up for the last seven years of the trial. The women in the intervention arm received the same amount of screening for the lung, colorectal and ovarian cancers. The remaining participants were enrolled in the control arm, where they received standard, usual care from their healthcare providers and were followed for 13 years. The intervention arm of the study represented “an organized, controlled, multi-faceted screening program,” said Berg. Usual care, while difficult to precisely quantify, represents the range of options offered in community healthcare settings, which are less well coordinated and where screening techniques may vary greatly. All participants had no previous history of a type of cancer that was being screened in the PLCO, and the data collected from them included dietary information, health status, screening information, and blood samples. The screening component of the trial was completed in 2006.

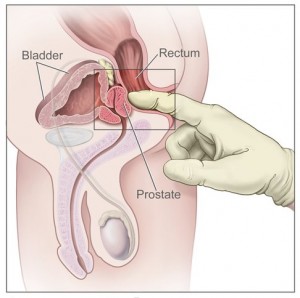

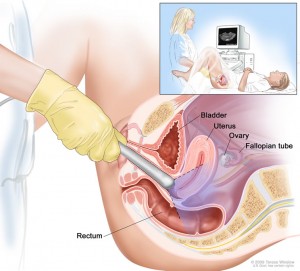

For prostate cancer, PLCO centers screened men with a digital rectal exam (DRE) and a blood test for prostate-specific antigen (PSA). For lung cancer, centers screened both men and women with a chest X-ray. For colorectal cancer, men and women were screened with flexible sigmoidoscopy. For ovarian cancer, women were screened with both a blood test for the tumor marker known as CA-125, and a technique known as transvaginal ultrasound.

PROSTATE

In the prostate part of the trial, 38,343 men were randomly assigned to six annual screenings (six PSA tests and four DREs). The other 38,350 men were randomly assigned to usual care, as recommended by their doctors, but received no recommendations for or against annual prostate cancer screening. After 13 years of follow-up, men who underwent prostate cancer screening with a PSA test administered in tandem with a DRE had a 12 percent higher incidence of prostate cancer than men in the control group, but similar rate of death from the disease. Mortality outcomes are the most important measures of screening efficacy.

Since the difference between the numbers of deaths in the two groups was not statistically significant, there was no detectable mortality benefit for prostate cancer screening vs. usual care. Due to the large number of men in the control arm who received prostate cancer screening it was not possible to make a definitive statement about the impact of screening on mortality. “This trial contributed to answering a very pressing question about prostate cancer screening and important issues about the effects of PSA testing were brought to light,” said Barnett Kramer, M.D., director of NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention. Because NCI’s mission is cancer research, it will fall to others to determine whether PSA should continue to be recommended as a screening technique. The U.S. Preventive Task Force, supported by the U.S. government’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality issues screening guidelines.

LUNG

Chest X-ray technology was commonly used for lung cancer screening at the time the PLCO trial began. Previous studies had not shown a benefit from this screening method, but those trials had limitations due to small size and results that were not definitive. Participants received annual screening with chest radiographs, or X-rays, for four years vs. usual medical care. Compared with usual care, the use of annual chest radiographs as a screening tool for lung cancer did not reduce lung cancer mortality, even in smokers. These findings were published soon after the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) results, since the intervention arm of this trial was used as the control arm for NLST. These results not only provided important information about the benefits and harms of annual chest radiographic screening, but also were a key component in facilitating the NLST trial. The NLST found that participants who were heavy smokers and who received low-dose helical CT scans as part of the trial had a 20 percent lower relative risk of dying from lung cancer than participants who received standard chest X-rays. The PLCO therefore acted as a stepping stone upon which other technologies, like helical CT used in NLST, could be evaluated.

COLORECTAL

Flexible sigmoidoscopy was a big improvement from previous sigmoidoscopy techniques, since older scopes were rigid and did not bend. However, in the intervening years since the PLCO study began, colonoscopy has become a more widespread screening tool. This became apparent when individuals in the control arm were getting more colonoscopies as part of their regular care. To address this, a sub-study called Study of Colonoscopy Utilization was initiated to help evaluate patterns of colonoscopy care.

The PLCO also confirmed results from similar studies that were previously done in the United Kingdom and Italy. There are additional ongoing studies in Europe that are looking at colorectal screening options that show promise to provide clearer evidence.

Recently, a new radiologic technique called virtual colonoscopy has been developed. This method examines the inside of the colon by taking a series of X-rays. A computer is used to make 2-dimensional (2-D) and 3-D pictures of the colon from these X-rays. The pictures can be saved, changed to give better viewing angles, and reviewed after the procedure, even years later. Virtual colonoscopy most frequently involves the same preparation as a regular colonoscopy, although new techniques are under investigation to image the colon without the bowel preparation. With virtual colonoscopy, if an abnormality is found, a regular colonoscopy has to be performed, which is a more invasive procedure.

OVARIAN

Women in the screening arm were offered annual screening with transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125, whereas those randomized to the control group received their usual care, which usually did not involve screening for ovarian cancer. Trial results showed that simultaneous screening with a blood test for the biomarker CA-125 along with a transvaginal ultrasound, compared with usual care, did not reduce ovarian cancer mortality in women. The results also showed that diagnostic evaluation following a false-positive result was associated with potentially harmful complications. “These results made it clear that more research is needed when it comes to ovarian cancer screening. Based on these findings, CA-125 and transvaginal ultrasound should not be used for ovarian cancer routine screening,” said Berg. “Certain groups, who are at higher risk, should see specialists to discuss their options.”

Most women with ovarian cancer are diagnosed with advanced stage disease, making the need to find a test that can detect the disease at an early stage a high priority.

BIOMARKERS

Another important aspect of the PLCO trial is The Etiology and Early Marker Studies. By collecting biospecimens, such as blood samples, from trial participants, a valuable resource for cancer research, cancer etiology and early markers has been established. In addition to blood specimens being collected, tumors diagnosed in individuals were also retrieved from the pathology departments (after appropriate permissions were granted), along with adenomas from those participants diagnosed with colorectal cancer. This collection of tumors, adenomas and blood samples provides an invaluable biospecimen resource for cancer researchers. These tools can be looked at to see the types of molecular changes in tumors and look at blood specimens to search for biomarkers for early detection. “This resource will be a major lasting contribution of PLCO to cancer research,” said Berg.

Perhaps, still to be determined, is the effect of the PLCO trial on public health. “This trial yielded some definitive health outcomes, both positive and negative,” said Kramer. “This is the most efficient type of study design, where you can directly compare the benefits and harms of a given screening test. In addition, the data collected can be used to discover markers to predict risk for cancer and potentially help design screening tests for the future.”

More insights from Dr. Kramer are available in the video posted below:

Print This Post

Print This Post

NCI NewsCenter

NCI NewsCenter NCI Budget Data

NCI Budget Data Visuals Online

Visuals Online NCI Fact Sheets

NCI Fact Sheets Understanding Cancer Series

Understanding Cancer Series