Report to the President and the Congress on Comparative Effectiveness ResearchEXECUTIVE SUMMARYAcross the United States, clinicians and patients confront important health care decisions without adequate information. What is the best pain management regimen for disabling arthritis in an elderly African-American woman with heart disease? For neurologically impaired children with special health care needs, what care coordination approach is most effective at preventing hospital readmissions? What treatments are most beneficial for patients with depression who have other medical illnesses? Can physicians tailor therapy to specific groups of patients using their history or special diagnostic tests? What interventions work best to prevent obesity or tobacco use? Unfortunately, the answer to these types of comparative, patient-centered questions in health care is often, “We don’t really know.” Thousands of health care decisions are made daily; patient-centered comparative effectiveness research focuses on filling gaps in evidence needed by clinicians and patients to make informed decisions. Physicians and other clinicians see patients every day with common ailments, and they sometimes are unsure of the best treatment because limited or no evidence comparing treatment options for the condition exists. As a result, patients seen by different clinicians may get different treatments and unknowingly be receiving less effective care. Patients and their caregivers search in vain on the Internet or elsewhere for evidence to help guide their decisions. They often fail to find this information either because it does not exist or because it has never been collected and synthesized to inform patients and/or their caregivers in patient-friendly language. When they do find information, it may be informed by marketing objectives, not the best evidence. Due to astonishing achievements in biomedical science, clinicians and patients often have a plethora of choices when making decisions about diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, but it is frequently unclear which therapeutic choice works best for whom, when, and in what circumstances. The purpose of comparative effectiveness research (CER) is to provide information that helps clinicians and patients choose which option best fits an individual patient's needs and preferences. It also can inform the health choices of those Americans who cannot or choose not to access the health care system. Clinicians and patients need to know not only that a treatment works on average but also which interventions work best for specific types of patients (e.g. the elderly, racial and ethnic minorities). Policy makers and public health professionals need to know what approaches work to address the prevention needs of those Americans who do not access health care. This information is essential to translating new discoveries into better health outcomes for Americans, accelerating the application of beneficial innovations, and delivering the right treatment to the right patient at the right time. Examples of successful CER include summaries of evidence from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) on numerous conditions, such as prostate cancer and osteoporosis, as well as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) diabetes prevention trial that demonstrated lifestyle change was superior to metformin and placebo in preventing onset of type 2 diabetes. Additionally, the Veterans Affairs (VA) COURAGE trial demonstrated that patients treated with optimal medical therapy alone did just as well as patients who received percutaneous coronary intervention plus medical therapy in preventing heart attack and death. These exemplars show the power of CER to inform patient and clinician decisions and improve health outcomes. Patients increasingly and appropriately want to take responsibility for their care. Therefore we have a responsibility to provide comparative information to enable informed decision-making. This patient-centered, pragmatic, “real world” research is a fundamental requirement for improving care for all Americans. Comparative effectiveness differs from efficacy research because it is ultimately applicable to real-world needs and decisions faced by patients, clinicians, and other decision makers. In efficacy research, such as a drug trial for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, the question is typically whether the treatment is efficacious under ideal, rather than real-world, settings. The results of such studies are therefore not necessarily generalizable to any given patient or situation. But what patients and clinicians often need to know in practice is which treatment is the best choice for a particular patient. In this way, comparative effectiveness is much more patient-centered. Comparative effectiveness has even been called patient-centered health research or patient-centered outcomes research to illustrate its focus on patient needs. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) provided $1.1 billion for comparative effectiveness research. The Act allocated $400 million to the Office of the Secretary in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), $400 million to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and $300 million to the HHS Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It also established the Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness Research (the Council) to foster optimum coordination of CER conducted or supported by Federal departments and agencies. Furthermore, the legislation indicated that “the Council shall submit to the President and the Congress a report containing information describing current Federal activities on comparative effectiveness research and recommendations for such research conducted or supported from funds made available for allotment by the Secretary for comparative effectiveness research in this Act” by June 30, 2009. Transparent, Open Process Seeking Public Input From the outset, the Council recognized the importance of establishing a transparent, collaborative process for making recommendations and sought the input of the American people on this important topic. The Council held three public listening sessions, two in the District of Columbia and one in Chicago. The Council also received comments for two months on its public Web site. Importantly, the open process allowed the Council to hear from hundreds of diverse stakeholders who represent views across the spectrum. Many patients expressed their need for this type of research; one of the most emotional and moving testimonies came from the mother of a child with a seizure disorder in Chicago who had struggled to find the best treatment for her child. A physician from the American Board of Orthopedics summarized many physicians’ testimony by saying, “developing high quality, objective information will improve informed patient choice, shared decision-making, and the clinical effectiveness of physician treatment recommendations.” The Council heard repeatedly at the listening sessions that the Federal Government must use this investment to lay the foundation for informing decisions and improving the quality of health care. In addition, the Council posted interim working documents for feedback, including the definition of CER, the prioritization criteria, and the strategic framework, and modified these based on the feedback. Comments from the listening sessions and via the Web site significantly influenced Council discussion and decisions. Indeed, this entire report is influenced by the public input—and Appendix A elaborates on the key themes that ran through the public comments. Vision The Council’s vision for the investment in comparative effectiveness research focuses on laying the foundation for this type of research to develop and prosper so it can inform decisions by patients and clinicians. This research is critical to transforming our health care system to deliver higher quality and more value to all Americans. The Council specifically focused on recommendations for use of the Office of Secretary (OS) funds to fill high priority gaps that were less likely to be funded by other organizations and therefore represent unique opportunities for these funds.

Definition and Criteria The Council first established a definition, building on previous definitions, for comparative effectiveness research: Comparative effectiveness research is the conduct and synthesis of research comparing the benefits and harms of different interventions and strategies to prevent, diagnose, treat and monitor health conditions in “real world” settings. The purpose of this research is to improve health outcomes by developing and disseminating evidence-based information to patients, clinicians, and other decision-makers, responding to their expressed needs, about which interventions are most effective for which patients under specific circumstances.

The Council needed explicit criteria to make recommendations for priorities. Therefore, the Council’s second step was to establish minimum threshold criteria that must be met and prioritization criteria. Minimum Threshold Criteria (i.e. must meet these to be considered):

The prioritization criteria for scientifically meritorious research and investments are:

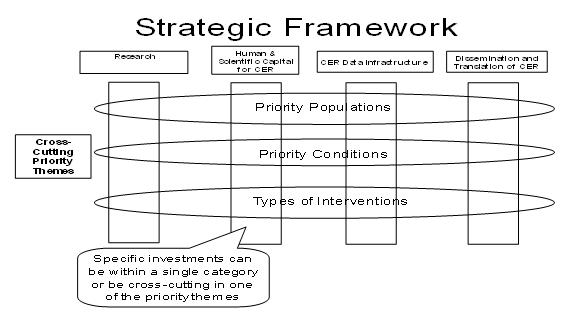

Importance of Priority Populations and Patient Sub-Groups One important consideration for comparative effectiveness research is addressing the needs of priority populations and sub-groups, i.e., those often underrepresented in research. The priority populations specifically include, but are not limited to, racial and ethnic minorities, persons with disabilities, children, the elderly, and patients with multiple chronic conditions. These groups have been traditionally under-represented in medical research. In addition, comparative effectiveness should complement the trend in medicine to develop personalized medicine—the ability to customize a drug and dose based on individual patient and disease characteristics. One of the advantages of large comparative effectiveness studies is the power to investigate effects at the sub-group level that often cannot be determined in a randomized trial. This power needs to be harnessed so personalized medicine and comparative effectiveness complement each other. Strategic Framework After completing the draft definition and criteria for prioritization of potential CER investments, the Council recognized the need to develop a strategic framework for CER activity and investments to categorize current activity, identify gaps, and inform decisions on high-priority recommendations. This framework represents a comprehensive, coordinated approach to CER priorities. It is intended to support immediate decisions for investment in CER priorities and to provide a comprehensive foundation for longer-term strategic decisions on CER priorities and the related infrastructure. At the framework’s core is responsiveness to expressed needs for comparative effectiveness research to inform health care decision-making by patients, clinicians, and others in the clinical and public health communities. Types of CER investments and activities can be grouped into four major categories:

Furthermore, investments or activities related to a specific theme can cut across one or more categories and may include research, human and scientific capital, CER data infrastructure, and/or translation and adoption. These themes could include:

Together, these activities and themes make up the “CER Strategic Framework” (Figure A) Figure A CER Inventory and Priority-Setting Process The Council also conducted an inventory of CER and data infrastructure to help identify gaps in the current CER landscape. Maintaining that inventory and ongoing evaluation of government and private sector (where possible) CER investments and programs across these activities and themes is critical to this framework’s value for decision-making. The first draft Federal Government inventory of CER and data infrastructure is included in this report, but it is critical to note that evaluation of current activities and the identification of gaps in order to inform priority-setting must be iterative and continue in the future. As noted above, the Council’s priority-setting process was informed by public input, and that input had a substantial influence on how the Council formulated its framework and priorities for CER. CER is an important mechanism to improve health and continued public input is vital for agenda setting. Priority Recommendations In developing its recommendations for how to invest the OS ARRA funding of $400 million, the Council sought to respond to patient and physician needs for CER, to balance achieving near-term results with building longer-term opportunities, and to capture the unique value that the Secretary’s ARRA funds could play in filling gaps and building the foundation for future CER. The Council recommended that, among the four major activities and three cross-cutting themes in the CER framework, the primary investment for this funding should be data infrastructure. Data infrastructure could include linking current data sources to enable answering CER questions, development of distributed electronic data networks and patient registries, and partnerships with the private sector. Secondary areas of investment are dissemination and translation of CER findings, priority populations, and priority types of interventions. The priority populations identified that could be the focus of cross-cutting themes were racial and ethnic minorities, persons with disabilities, persons with multiple chronic conditions (including co-existing mental illness), the elderly, and children. CER will be an important tool to inform decisions for these populations and reduce health disparities. High-priority interventions for OS to consider supporting include medical and assistive devices, procedures/surgery, behavioral change, prevention, and delivery systems. For example, behavioral change and prevention have the potential to decrease obesity, decrease smoking rates, increase adherence to medical therapies, and improve many other factors that determine health. Delivery system interventions, such as comparing different discharge and transitions of care processes on hospital readmissions, community-based care models, or testing the effect of different medical home models on health have substantial potential to drive better health outcomes for patients. The OS funds may also play a supporting role in research and human and scientific capital. Because the Council anticipates that AHRQ, NIH, and VA will likely continue to play a major role in these essential activities for the CER enterprise, OS funding would likely only fill gaps in these areas. Longer-Term Outlook and Next Steps This report and an Institute of Medicine report funded by the Department will inform the priority-setting process for CER-related funding. The most immediate next step will be the development of a specific plan, to be submitted by July 30, 2009, from the Secretary of Health and Human Services for the combined $1.1 billion of ARRA CER funding. In addition, an annual report from the Council is required under the ARRA legislation. It will be important for this funding both to accomplish short-term successes and to build the foundation for future CER. The CER activity and investments should be coordinated across the Federal Government and avoid duplicative effort. In addition, the funding should complement and link to activities and funding in the private sector to maximize the benefits to the American people. Clinicians, patients, and other stakeholders greatly need comparative effectiveness research to inform health care decisions. One private citizen unaffiliated with any health care group summarized, “It is more important than ever to engage in robust research on what treatments work and what do not. Doing so empowers doctors and patients, and helps make our practice of medicine more evidence-based.” This is a unique opportunity to invest in the fundamental building blocks for transformation of health care in the United States to improve the quality and value of health care for all Americans. Physicians and patients deserve the best patient-centered evidence on what works, so Americans can have the highest quality care and achieve the best possible outcomes. |

|