A federal government Website managed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

200 Independence Avenue, S.W.

Washington, D.C. 20201

Related Websites

Additional Information

Long ago, physicians realized that people who had recovered from the plague would never get it again—they had acquired immunity. This is because some of the activated T and B cells had become memory cellsmemory cells. Memory cells ensure that the next time a person meets up with the same antigen, the immune system is already set to demolish it.

Immunity can be strong or weak, short-lived or long-lasting, depending on the type of antigen it encounters, the amount of antigen, and the route by which the antigen enters the body. Immunity can also be influenced by inherited genes. When faced with the same antigen, some individuals will respond forcefully, others feebly, and some not at all.

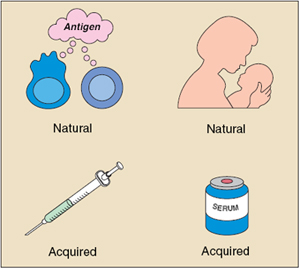

An immune response can be sparked not only by infection but also by immunization with vaccines. Some vaccines contain microorganisms—or parts of microorganisms— that have been treated so they can provoke an immune response but not full-blown disease.

Immunity can also be transferred from one individual to another by injections of serum rich in antibodies against a particular microbe (antiserum). For example, antiserum is sometimes given to protect travelers to countries where hepatitis A is widespread. The antiserum induces passive immunity against the hepatitis A virus. Passive immunity typically lasts only a few weeks or months.

Infants are born with weak immune responses but are protected for the first few months of life by antibodies they receive from their mothers before birth. Babies who are nursed can also receive some antibodies from breast milk that help to protect their digestive tracts.

Immune tolerance is the tendency of T or B lymphocytes to ignore the body’s own tissues. Maintaining tolerance is important because it prevents the immune system from attacking its fellow cells. Scientists are hard at work trying to understand how the immune system knows when to respond and when to ignore an antigen.

Tolerance occurs in at least two ways—central tolerance and peripheral tolerance. Central tolerance occurs during lymphocyte development. Very early in each immune cell’s life, it is exposed to many of the self molecules in the body. If it encounters these molecules before it has fully matured, the encounter activates an internal self-destruct pathway, and the immune cell dies. This process, called clonal deletion, helps ensure that “self-reactive” T cells and B cells, those that could develop the ability to destroy the body’s own cells, do not mature and attack healthy tissues.

Because maturing lymphocytes do not encounter every molecule in the body, they must also learn to ignore mature cells and tissues. In peripheral tolerance, circulating lymphocytes might recognize a self molecule but cannot respond because some of the chemical signals required to activate the T or B cell are absent. So-called clonal anergy, therefore, keeps potentially harmful lymphocytes switched off. Peripheral tolerance may also be imposed by a special class of regulatory T cells that inhibits helper or cytotoxic T-cell activation by self antigens.

For many years, healthcare providers have used vaccination to help the body’s immune system prepare for future attacks. Vaccines consist of killed or modified microbes, parts of microbes, or microbial DNA that trick the body into thinking an infection has occurred.

A vaccinated person’s immune system attacks the harmless vaccine and prepares for invasions against the kind of microbe the vaccine contained. In this way, the person becomes immunized against the microbe. Vaccination remains one of the best ways to prevent infectious diseases, and vaccines have an excellent safety record. Previously devastating diseases such as smallpox, polio, and whooping cough (pertussis) have been greatly controlled or eliminated through worldwide vaccination programs.

Last syndicated: April 16, 2012

This content is brought to you by: National Institute of Allergy Infectious Diseases