For more information, visit http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/ipf/

What Is Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis?

Pulmonary fibrosis (PULL-mun-ary fi-BRO-sis) is a disease in which tissue deep in your lungs becomes thick and stiff, or scarred, over time. The formation of scar tissue is called fibrosis.

As the lung tissue thickens, your lungs can't properly move oxygen into your bloodstream. As a result, your brain and other organs don't get the oxygen they need. (For more information, go to the "How the Lungs Work" section of this article.)

Sometimes doctors can find out what's causing fibrosis. But in most cases, they can't find a cause. They call these cases idiopathic (id-ee-o-PATH-ick) pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

IPF is a serious disease that usually affects middle-aged and older adults. IPF varies from person to person. In some people, fibrosis happens quickly. In others, the process is much slower. In some people, the disease stays the same for years.

IPF has no cure yet. Many people live only about 3 to 5 years after diagnosis. The most common cause of death related to IPF is respiratory failure. Other causes of death include pulmonary hypertension (HI-per-TEN-shun), heart failure, pulmonary embolism (EM-bo-lizm), pneumonia (nu-MO-ne-ah), and lung cancer.

Genetics may play a role in causing IPF. If more than one member of your family has IPF, the disease is called familial IPF.

Research has helped doctors learn more about IPF. As a result, they can more quickly diagnose the disease now than in the past. Also, researchers are studying several medicines that may slow the progress of IPF. These efforts may improve the lifespan and quality of life for people who have the disease.

How the Lungs Work

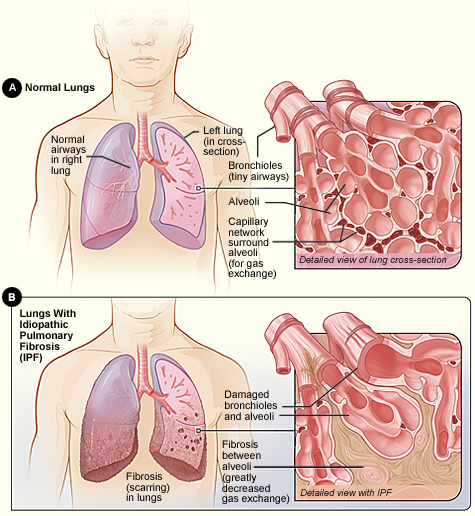

To understand idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), it helps to understand how the lungs work. The air that you breathe in through your nose or mouth travels down through your trachea (windpipe) into two tubes in your lungs called bronchial (BRONG-ke-al) tubes or airways.

The airways are shaped like an upside-down tree with many branches. The windpipe is the trunk. It splits into two bronchial tubes, or bronchi. Thinner tubes called bronchioles branch out from the bronchi.

The bronchioles end in tiny air sacs called alveoli (al-VEE-uhl-eye). These air sacs have very thin walls, and small blood vessels called capillaries run through them. There are about 300 million alveoli in a normal lung.

When the air that you've just breathed in reaches these air sacs, the oxygen in the air passes through the air sac walls into the blood in the capillaries. At the same time, carbon dioxide (a waste gas) moves from the capillaries into the air sacs. This process is called gas exchange.

The oxygen-rich blood in the capillaries then flows into larger veins, which carry it to the heart. Your heart pumps the oxygen-rich blood to all your body's organs. These organs can't function without an ongoing supply of oxygen.

The animation below shows how the lungs work. Click the "start" button to play the animation. Written and spoken explanations are provided with each frame. Use the buttons in the lower right corner to pause, restart, or replay the animation, or use the scroll bar below the buttons to move through the frames.

The animation shows how the lungs inhale oxygen and transfer it to the blood. It also shows how carbon dioxide (a waste product) is removed from the blood and exhaled.

In IPF, scarring begins in the air sac walls and the spaces around them. The scarring makes the walls of the air sacs thicker. This makes it harder for oxygen to pass through the air sac walls into the bloodstream.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

Figure A shows the location of the lungs and airways in the body. The inset image shows a detailed view of the lung's airways and air sacs in cross-section. Figure B shows fibrosis (scarring) in the lungs. The inset image shows a detailed view of the fibrosis and how it damages the airways and air sacs.

For more information about lung function, go to the Health Topics How the Lungs Work article.

Other Names for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Idiopathic diffuse interstitial pulmonary fibrosis

- Pulmonary fibrosis of unknown cause

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis

- Usual interstitial pneumonitis

- Diffuse fibrosing alveolitis

What Causes Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis?

Sometimes doctors can find out what is causing pulmonary fibrosis (lung scarring). For example, exposure to environmental pollutants and certain medicines can cause the disease.

Environmental pollutants include inorganic dust (silica and hard metal dusts) and organic dust (bacteria and animal proteins).

Medicines that are known to cause pulmonary fibrosis in some people include nitrofurantoin (an antibiotic), amiodarone (a heart medicine), methotrexate and bleomycin (both chemotherapy medicines), and many other medicines.

In most cases, however, the cause of lung scarring isn’t known. These cases are called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). With IPF, doctors think that something inside or outside of the lungs attacks them again and again over time.

These attacks injure the lungs and scar the tissue inside and between the air sacs. This makes it harder for oxygen to pass through the air sac walls into the bloodstream.

The following factors may increase your risk of IPF:

- Cigarette smoking

- Viral infections, including Epstein-Barr virus (which causes mononucleosis), influenza A virus, hepatitis C virus, HIV, and herpes virus 6

Genetics also may play a role in causing IPF. Some families have at least two members who have IPF.

Researchers have found that 9 out of 10 people who have IPF also have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). GERD is a condition in which acid from your stomach backs up into your throat.

Some people who have GERD may regularly breathe in tiny drops of acid from their stomachs. The acid can injure their lungs and lead to IPF. More research is needed to confirm this theory.

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis?

The signs and symptoms of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) develop over time. They may not even begin to appear until the disease has done serious damage to your lungs. Once they occur, they're likely to get worse over time.

The most common signs and symptoms are:

- Shortness of breath. This usually is the main symptom of IPF. At first, you may be short of breath only during exercise. Over time, you'll likely feel breathless even at rest.

- A dry, hacking cough that doesn't get better. Over time, you may have repeated bouts of coughing that you can't control.

Other signs and symptoms that you may develop over time include:

- Rapid, shallow breathing

- Gradual, unintended weight loss

- Fatigue (tiredness) or malaise (a general feeling of being unwell)

- Aching muscles and joints

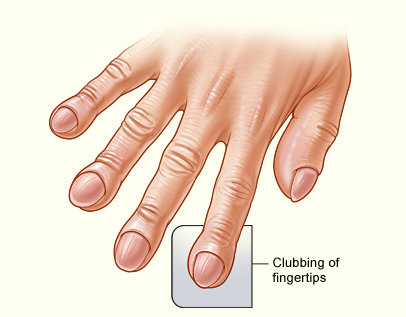

- Clubbing, which is the widening and rounding of the tips of the fingers or toes

Clubbing

The illustration shows clubbing of the fingertips associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

IPF may lead to other medical problems, including a collapsed lung, lung infections, blood clots in the lungs, and lung cancer.

As the disease worsens, you may develop other potentially life-threatening conditions, including respiratory failure, pulmonary hypertension, and heart failure.

How Is Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Diagnosed?

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) causes the same kind of scarring and symptoms as some other lung diseases. This makes it hard to diagnose.

Seeking medical help as soon as you have symptoms is important. If possible, seek care from a pulmonologist. This is a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating lung problems.

Your doctor will diagnose IPF based on your medical history, a physical exam, and test results. Tests can help rule out other causes of your symptoms and show how badly your lungs are damaged.

Medical History

Your doctor may ask about:

- Your age

- Your history of smoking

- Things in the air at your job or elsewhere that could irritate your lungs

- Your hobbies

- Your history of legal and illegal drug use

- Other medical conditions that you have

- Your family's medical history

- How long you've had symptoms

Diagnostic Tests

No single test can diagnose IPF. Your doctor may recommend several of the following tests.

Chest X Ray

A chest x ray is a painless test that creates a picture of the structures in your chest, such as your heart and lungs. This test can show shadows that suggest scar tissue. However, many people who have IPF have normal chest x rays at the time they're diagnosed.

High-Resolution Computed Tomography

A high-resolution computed tomography scan, or HRCT scan, is an x ray that provides sharper and more detailed pictures than a standard chest x ray.

HRCT can show scar tissue and how much lung damage you have. This test can help your doctor spot IPF at an early stage or rule it out. HRCT also can help your doctor decide how likely you are to respond to treatment.

Lung Function Tests

Your doctor may suggest a breathing test called spirometry (spi-ROM-eh-tree) to find out how much lung damage you have. This test measures how much air you can blow out of your lungs after taking a deep breath. Spirometry also measures how fast you can breathe the air out.

If you have a lot of lung scarring, you won't be able to breathe out a normal amount of air.

Pulse Oximetry

For this test, your doctor attaches a small sensor to your finger or ear. The sensor uses light to estimate how much oxygen is in your blood.

Arterial Blood Gas Test

For this test, your doctor takes a blood sample from an artery, usually in your wrist. The sample is sent to a laboratory, where its oxygen and carbon dioxide levels are measured.

This test is more accurate than pulse oximetry. The blood sample also can be tested to see whether an infection is causing your symptoms.

Skin Test for Tuberculosis

For this test, your doctor injects a substance under the top layer of skin on one of your arms. This substance reacts to tuberculosis (TB). If you have a positive reaction, a small hard lump will develop at the injection site 48 to 72 hours after the test. This test is done to rule out TB.

Exercise Testing

Exercise testing shows how well your lungs move oxygen and carbon dioxide in and out of your bloodstream when you're active. During this test, you walk or pedal on an exercise machine for a few minutes.

An EKG (electrocardiogram) checks your heart rate, a blood pressure cuff checks your blood pressure, and a pulse oximeter shows how much oxygen is in your blood.

Your doctor may place a catheter (a flexible tube) in an artery in one of your arms to draw blood samples. These samples will provide a more precise measure of the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in your blood.

Your doctor also may ask you to breathe into a tube that measures oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in your blood.

Lung Biopsy

For a lung biopsy, your doctor will take samples of lung tissue from several places in your lungs. The samples are examined under a microscope. A lung biopsy is the best way for your doctor to diagnose IPF.

This procedure can help your doctor rule out other conditions, such as sarcoidosis (sar-koy-DO-sis), cancer, or infection. Lung biopsy also can show your doctor how far your disease has advanced.

Doctors use several procedures to get lung tissue samples.

Video-assisted thoracoscopy (thor-ah-KOS-ko-pee). This is the most common procedure used to get lung tissue samples. Your doctor inserts a small tube with an attached light and camera into your chest through small cuts between your ribs. The tube is called an endoscope.

The endoscope provides a video image of the lungs and allows your doctor to collect tissue samples. This procedure must be done in a hospital. You'll be given medicine to make you sleep during the procedure.

Bronchoscopy (bron-KOS-ko-pee). For a bronchoscopy, your doctor passes a thin, flexible tube through your nose or mouth, down your throat, and into your airways. At the tube's tip are a light and mini-camera. They allow your doctor to see your windpipe and airways.

Your doctor then inserts a forceps through the tube to collect tissue samples. You'll be given medicine to help you relax during the procedure.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BRONG-ko-al-VE-o-lar lah-VAHZH). During bronchoscopy, your doctor may inject a small amount of salt water (saline) through the tube into your lungs. This fluid washes the lungs and helps bring up cells from the area around the air sacs. These cells are examined under a microscope.

Thoracotomy (thor-ah-KOT-o-me). For this procedure, your doctor removes a few small pieces of lung tissue through a cut in the chest wall between your ribs. Thoracotomy is done in a hospital. You'll be given medicine to make you sleep during the procedure.

How Is Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Treated?

Doctors may prescribe medicines, oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), and lung transplant to treat idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Medicines

Currently, no medicines are proven to slow the progression of IPF.

Prednisone, azathioprine (A-zah-THI-o-preen), and N-acetylcysteine (a-SEH-til-SIS-tee-in) have been used to treat IPF, either alone or in combination. However, experts have not found enough evidence to support their use.

Prednisone

Prednisone is an anti-inflammatory medicine. You usually take it by mouth every day. However, your doctor may give it to you through a needle or tube inserted into a vein in your arm for several days. After that, you usually take it by mouth.

Because prednisone can cause serious side effects, your doctor may prescribe it for 3 to 6 months or less at first. Then, if it works for you, your doctor may reduce the dose over time and keep you on it longer.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine suppresses your immune system. You usually take it by mouth every day. Because it can cause serious side effects, your doctor may prescribe it with prednisone for only 3 to 6 months.

If you don't have serious side effects and the medicines seem to help you, your doctor may keep you on them longer.

N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine is an antioxidant that may help prevent lung damage. You usually take it by mouth several times a day.

A common treatment for IPF is a combination of prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine. However, this treatment was recently found harmful in a study funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

If you have IPF and take this combination of medicines, talk with your doctor. Do not stop taking the medicines on your own.

The NHLBI currently supports research to compare N-acetylcysteine treatment with placebo treatment (sugar pills) in patients who have IPF.

New Medicines Being Studied

Researchers, like those in the Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Network, are studying new treatments for IPF. With the support and guidance of the NHLBI, these researchers continue to look for new IPF treatments and therapies.

Some of these researchers are studying medicines that may reduce inflammation and prevent or reduce scarring caused by IPF.

If you're interested in joining a research study, talk with your doctor. For more information about ongoing research, go to the "Clinical Trials" section of this article.

Other Treatments

Other treatments that may help people who have IPF include the following:

- Flu and pneumonia vaccines may help prevent infections and keep you healthy.

- Cough medicines or oral codeine may relieve coughing.

- Vitamin D, calcium, and a bone-building medicine may help prevent bone loss if you're taking prednisone or another corticosteroid.

- Anti-reflux therapy may help control gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Most people who have IPF also have GERD.

Oxygen Therapy

If the amount of oxygen in your blood gets low, you may need oxygen therapy. Oxygen therapy can help reduce shortness of breath and allow you to be more active.

Oxygen usually is given through nasal prongs or a mask. At first, you may need it only during exercise and sleep. As your disease worsens, you may need it all the time.

For more information, go to the Health Topics Oxygen Therapy article.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

PR is now a standard treatment for people who have chronic (ongoing) lung disease. PR is a broad program that helps improve the well-being of people who have breathing problems.

The program usually involves treatment by a team of specialists in a special clinic. The goal is to teach you how to manage your condition and function at your best.

PR doesn't replace medical therapy. Instead, it's used with medical therapy and may include:

- Exercise training

- Nutritional counseling

- Education on your lung disease or condition and how to manage it

- Energy-conserving techniques

- Breathing strategies

- Psychological counseling and/or group support

For more information, go to the Health Topics Pulmonary Rehabilitation article.

Lung Transplant

Your doctor may recommend a lung transplant if your condition is quickly worsening or very severe. A lung transplant can improve your quality of life and help you live longer.

Some medical centers will consider patients older than 65 for lung transplants if they have no other serious medical problems.

The major complications of a lung transplant are rejection and infection. ("Rejection" refers to your body creating proteins that attack the new organ.) You will have to take medicines for the rest of your life to reduce the risk of rejection.

Because the supply of donor lungs is limited, talk with your doctor about a lung transplant as soon as possible.

For more information, go to the Health Topics Lung Transplant article.

Living With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

No cure is available for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) yet. Your symptoms may get worse over time. As your symptoms worsen, you may not be able to do many of the things that you did before you had IPF.

However, lifestyle changes and ongoing care can help you manage the disease.

Lifestyle Changes

If you're still smoking, the most important thing you can do is quit. Talk with your doctor about programs and products that can help you quit. Also, try to avoid secondhand smoke. Ask family members and friends not to smoke in front of you or in your home, car, or workplace.

If you have trouble quitting smoking on your own, consider joining a support group. Many hospitals, workplaces, and community groups offer classes to help people quit smoking.

For more information about how to quit smoking, go to the Health Topics Smoking and Your Heart article and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's (NHLBI's) "Your Guide to a Healthy Heart." Although these resources focus on heart health, they include general tips on how to quit smoking.

Staying active can help with both your physical and mental health. Physical activity can help you maintain your strength and lung function and reduce stress. Try moderate exercise, such as walking or riding a stationary bike. Ask your doctor about using oxygen while exercising.

As your condition advances, use a wheelchair or motorized scooter, or stay busy with activities that aren't physical in nature.

You also should follow a healthy diet. A healthy diet includes a variety of fruits and vegetables. It also includes whole grains, fat-free or low-fat dairy products, and protein foods, such as lean meats, poultry without skin, seafood, processed soy products, nuts, seeds, beans, and peas.

A healthy diet is low in sodium (salt), added sugars, solid fats, and refined grains. Solid fats are saturated fat and trans fatty acids. Refined grains come from processing whole grains, which results in a loss of nutrients (such as dietary fiber).

Eating smaller, more frequent meals may relieve stomach fullness, which can make it hard to breathe. If you need help with your diet, ask your doctor to arrange for a dietitian to work with you.

For more information about following a healthy diet, go to the NHLBI's "Your Guide to Lowering Your Blood Pressure With DASH" and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's ChooseMyPlate.gov Web site. Both resources provide general information about healthy eating.

Getting plenty of rest can increase your energy and help you deal with the stress of living with a serious condition like IPF.

Try to maintain a positive attitude; relaxation techniques may help you do this. These techniques also may help you avoid excessive oxygen intake caused by tension or overworked muscles.

Avoid situations that can make your symptoms worse. For example, avoid traveling by air or living at or traveling to high altitudes where the air is thin and the amount of oxygen in the air is low.

Ongoing Care

If you have IPF, you will need ongoing medical care. If possible, seek treatment from a doctor who specializes in IPF. These specialists often are located at major medical centers.

Treatment may relieve your symptoms and even slow or stop the fibrosis (scarring). Follow your treatment plan as your doctor advises. For example:

- Take your medicines as your doctor prescribes

- Make any changes in diet or exercise that your doctor recommends

- Keep all of your appointments with your doctor

- Enroll in pulmonary rehabilitation

As your condition worsens, you may need oxygen therapy full time. Some people who have IPF carry portable oxygen when they go out.

Emotional Issues and Support

Living with IPF may cause fear, anxiety, depression, and stress. Talk about how you feel with your health care team. Talking to a professional counselor also can help. If you're very depressed, your doctor may recommend medicines or other treatments that can improve your quality of life.

Joining a patient support group may help you adjust to living with IPF. You can see how other people who have the same symptoms have coped with them. Talk with your doctor about local support groups or check with an area medical center.

Support from family and friends also can help relieve stress and anxiety. Let your loved ones know how you feel and what they can do to help you.

Clinical Trials

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) is strongly committed to supporting research aimed at preventing and treating heart, lung, and blood diseases and conditions and sleep disorders.

NHLBI-supported research has led to many advances in medical knowledge and care. For example, this research has uncovered some of the causes of chronic lung diseases, as well as ways to prevent and treat these diseases.

Many more questions remain about lung diseases, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The NHLBI continues to support research aimed at learning more about these diseases. For example, NHLBI-supported research on IPF includes studies that explore:

- The natural history of familial IPF and its underlying causes

- How well N-acetylcysteine works alone and with other medicines to treat IPF

- The benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation for people who have IPF

Much of this research depends on the willingness of volunteers to take part in clinical trials. Clinical trials test new ways to prevent, diagnose, or treat various diseases and conditions.

For example, new treatments for a disease or condition (such as medicines, medical devices, surgeries, or procedures) are tested in volunteers who have the illness. Testing shows whether a treatment is safe and effective in humans before it is made available for widespread use.

By taking part in a clinical trial, you can gain access to new treatments before they're widely available. You also will have the support of a team of health care providers, who will likely monitor your health closely. Even if you don't directly benefit from the results of a clinical trial, the information gathered can help others and add to scientific knowledge.

If you volunteer for a clinical trial, the research will be explained to you in detail. You'll learn about treatments and tests you may receive, and the benefits and risks they may pose. You'll also be given a chance to ask questions about the research. This process is called informed consent.

If you agree to take part in the trial, you'll be asked to sign an informed consent form. This form is not a contract. You have the right to withdraw from a study at any time, for any reason. Also, you have the right to learn about new risks or findings that emerge during the trial.

For more information about clinical trials related to IPF, talk with your doctor. You also can visit the following Web sites to learn more about clinical research and to search for clinical trials:

- http://clinicalresearch.nih.gov

- www.clinicaltrials.gov

- www.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/index.htm

- www.researchmatch.org

Links to Other Information About Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

NHLBI Resources

- How the Lungs Work (Health Topics)

- Lung Diseases Information for the Public

- Lung Transplant (Health Topics)

- Oxygen Therapy (Health Topics)

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation (Health Topics)

- Respiratory Failure (Health Topics)

- Pulmonary Hypertension (Health Topics)

Non-NHLBI Resources

- Pulmonary Fibrosis (MedlinePlus)

Clinical Trials

- Clinical Trials (Health Topics)

- Current Research (ClinicalTrials.gov)

- NHLBI Clinical Trials

- NIH Clinical Research Trials and You (National Institutes of Health)

- Patient Recruitment for Studies Conducted by the NHLBI

- ResearchMatch (funded by the National Institutes of Health)