Aortic Aneurysm Fact Sheet

Download this fact sheet [PDF–336K]

An aortic aneurysm (AA) is a ballooning or dilatation of the aorta, the large artery that carries blood from the heart through the chest and abdomen. AAs are classified according to their location; in the chest, it is called a thoracic AA, in the abdomen an abdominal AA (AAA), and across both areas a thoracoabdominal AA.

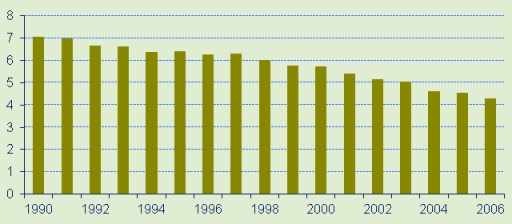

This graph shows the age-adjusted mortality rates from all aortic aneurysms (thoracic, abdominal, and thoracoabdominal). The rates prior to 1990 were stable near 7 per 100,000, but have declined over the past 15 years.1,2 Age-adjusted Mortality Rates for Aortic Aneurysm per 100,000.

Risk Factors for aortic aneurysm

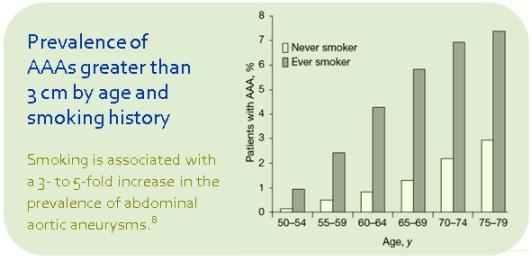

- History of smoking.

- Family history of aortic aneurysm.

- High blood pressure.

- High cholesterol.

- Atherosclerosis.

- Inherited conditions such as Marfan’s syndrome.

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms (AAA)

In addition to the risk factors noted above, infection and trauma can also cause AAA, although most are associated with atherosclerosis.3 A normal abdominal aorta is approximately 2.0 cm in diameter. An abdominal aneurysm places stress on the wall of the aorta. The risk of rupture for an AAA over 5cm in diameter is approximately 20%, over 6cm approximately 40%, and over 7cm over 50%. Rupture of an AAA carries a risk of death up to 90%.4

AAA is more common in men and in individuals aged 65 years and older. AAA is less common in women and with black race/ethnicity.5 AAA (from 2.9–4.9cm diameter) are present in 1.3% of men aged 45–54 years and 12.5% of men aged 75–84 years. Equivalent figures for women are 0% and 5.2% in each age group, respectively.6

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Aortic Dissection

Thoracic aortic aneurysms occur equally among men and women, and increase in frequency with older age.4 Thoracic aortic aneurysms are sometimes associated with inherited conditions involving connective tissue, including Marfan’s syndrome and, less frequently, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Marfan’s syndrome has an incidence of 1 of 10,000 persons. In persons with Marfan’s syndrome, the wall of the aorta weakens and stretches. Thoracic AA are also associated with high blood pressure. The incidence rate of thoracic aortic aneurysms is approximately 10.4 per 100,000 person-years.7

Aortic dissection occurs when a tear develops in the lining of the wall of the aorta. This can occur anywhere in the aorta but occurs more often in the thoracic aorta. It is associated with high blood pressure but can also occur from trauma. Aortic dissection can lead to aneurysm formation. The incidence rate of aortic dissection is estimated at 2.9 to 3.5 per 100,000 person-years. Approximately two-thirds of those with an aortic dissection are male.7

Figure A shows a normal aorta. Figure B shows a thoracic aortic aneurysm (which is located behind the heart). Figure C shows an abdominal aortic aneurysm located below the arteries that supply blood to the kidneys. (Courtesy NHLBI, http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/)

Figure A shows a normal aorta. Figure B shows a thoracic aortic aneurysm (which is located behind the heart). Figure C shows an abdominal aortic aneurysm located below the arteries that supply blood to the kidneys. (Courtesy NHLBI, http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/)

Symptoms of Aortic Aneurysms

The most common symptom associated with AA is pain in the affected region: thoracic AA causes pain in the chest or upper back, and AAA results in pain in the abdomen or lower back.

Sudden pain in the chest or upper back for thoracic AA, and in the abdomen or lower back that may radiate to the buttocks, groin, or legs for AAA, may signal growth, dissection, or rupture.9

Other Types of Aneurysms

Aneurysms can occur in many other parts of the body besides the aorta, such as in the brain (cerebral aneurysm), in the groin (femoral aneurysm), or behind the knee (popliteal aneurysm). Cerebral aneurysms can rupture and cause a stroke. Popliteal aneurysms can often be felt as a pulsatile bulge behind the knee. Aneurysms can also be caused by serious infections. Specific treatment is determined by your physician, based on your particular medical history and the size and location of the aneurysm.

Prevention and Treatment of Aortic Aneurysms

Prevention/Treatment: The most effective means of AA prevention is reduction of risk factors: smoking cessation, and control of high blood pressure and high cholesterol. Medications may help reduce the risk of complications with AA. When AA reach a certain size or interfere with surrounding blood vessels or organs, surgical repair or placement of a stent in the aorta may become necessary.9, 10

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for AAA using ultrasound imaging one-time for men aged 65–75 years that have ever smoked, even if they have no symptoms.5 Men aged 60 years and older with a family history of AAA may also be tested.9

Diagnosing Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

AAA can be diagnosed with noninvasive imaging tests including ultrasound and computed tomography (CT).

For More Information

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed Mortality File 1999–2006. CDC WONDER On-line Database, compiled from Compressed Mortality File 1999-2006 Series 20 No. 2L, 2009. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed Mortality File 1979–1998. CDC WONDER On-line Database, compiled from Compressed Mortality File CMF 1968–1988, Series 20, No. 2A, 2000 and CMF 1989–1998, Series 20, No. 2E, 2003. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd9.html.

- Creager MA, Loscalzo J. Diseases of the Aorta. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al., eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 17e ed.

- Clouse WD, Hallett JW, Jr., Schaff HV, Gayari MM, Ilstrup DM, Melton LJ, 3rd. Improved prognosis of thoracic aortic aneurysms: a population-based study. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1926–1929.

- Guirguis-Blake J, Wolff TA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurism. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(11):2154–2155.

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):e46–e215.

- Ramanath VS, Oh JK, Sundt TM, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes and thoracic aortic aneurysm. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(5):465–481.

- Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Bell TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: A best-evidence systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. AHRQ Pub. No. 05-0569-B. 2005.

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): Circulation. 2006;113(11):e463–654.

- Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(14):e27–e129.

Get email updates

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Contact Us:

- CDC/NCCDPHP/DHDSP

4770 Buford Hwy, NE

Mail Stop F-72

Atlanta, GA 30341-3717 - Call: 800-CDC-INFO

TTY: 800-232-6348

Fax: 770-488-8151 - cdcinfo@cdc.gov