About This Booklet

This National Cancer Institute (NCI) booklet (NIH Publication No. 06-1561) is about ovarian epithelial cancer. It is the most common type of ovarian cancer. It begins in the tissue that covers the ovaries.

You will read about possible causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. You will also find lists of questions to ask your doctor. It may help to take this booklet with you to your next appointment.

This booklet is not about ovarian germ cell tumors or other types of ovarian cancer. To find out about these types of ovarian cancer, please visit our Web site at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/ovarian. Or, contact our Cancer Information Service. We can answer your questions about cancer. We can send you NCI booklets, fact sheets, and other materials. You can call 1-800-4-CANCER or instant message us at LiveHelp (http://www.cancer.gov/livehelp).

The Ovaries

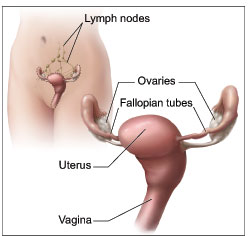

The ovaries are part of a woman's reproductive system. They are in the pelvis. Each ovary is about the size of an almond.

The ovaries make the female hormones — estrogen and progesterone. They also release eggs. An egg travels from an ovary through a fallopian tube to the womb (uterus).

When a woman goes through her "change of life" (menopause), her ovaries stop releasing eggs and make far lower levels of hormones.

|

| This picture is of the ovaries and nearby organs. |

Understanding Cancer

Cancer begins in cells, the building blocks that make up tissues. Tissues make up the organs of the body.

Normally, cells grow and divide to form new cells as the body needs them. When cells grow old, they die, and new cells take their place.

Sometimes, this orderly process goes wrong. New cells form when the body does not need them, and old cells do not die when they should. These extra cells can form a mass of tissue called a growth or tumor.

Tumors can be benign or malignant:

- Benign tumors are not cancer:

- Benign tumors are rarely life-threatening.

- Generally, benign tumors can be removed. They usually do not grow back.

- Benign tumors do not invade the tissues around them.

- Cells from benign tumors do not spread to other parts of the body.

- Malignant tumors are cancer:

- Malignant tumors are generally more serious than benign tumors. They may be life-threatening.

- Malignant tumors often can be removed. But sometimes they grow back.

- Malignant tumors can invade and damage nearby tissues and organs.

- Cells from malignant tumors can spread to other parts of the body. Cancer cells spread by breaking away from the original (primary) tumor and entering the lymphatic system or bloodstream. The cells invade other organs and form new tumors that damage these organs. The spread of cancer is called metastasis.

Benign and Malignant Cysts

An ovarian cyst may be found on the surface of an ovary or inside it. A cyst contains fluid. Sometimes it contains solid tissue too. Most ovarian cysts are benign (not cancer).

Most ovarian cysts go away with time. Sometimes, a doctor will find a cyst that does not go away or that gets larger. The doctor may order tests to make sure that the cyst is not cancer.

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer can invade, shed, or spread to other organs:

- Invade: A malignant ovarian tumor can grow and invade organs next to the ovaries, such as the fallopian tubes and uterus.

- Shed: Cancer cells can shed (break off) from the main ovarian tumor. Shedding into the abdomen may lead to new tumors forming on the surface of nearby organs and tissues. The doctor may call these seeds or implants.

- Spread: Cancer cells can spread through the lymphatic system to lymph nodes in the pelvis, abdomen, and chest. Cancer cells may also spread through the bloodstream to organs such as the liver and lungs.

When cancer spreads from its original place to another part of the body, the new tumor has the same kind of abnormal cells and the same name as the original tumor. For example, if ovarian cancer spreads to the liver, the cancer cells in the liver are actually ovarian cancer cells. The disease is metastatic ovarian cancer, not liver cancer. For that reason, it is treated as ovarian cancer, not liver cancer. Doctors call the new tumor "distant" or metastatic disease.

Risk Factors

Doctors cannot always explain why one woman develops ovarian cancer and another does not. However, we do know that women with certain risk factors may be more likely than others to develop ovarian cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of developing a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for ovarian cancer:

- Family history of cancer: Women who have a mother, daughter, or sister with ovarian cancer have an increased risk of the disease. Also, women with a family history of cancer of the breast, uterus, colon, or rectum may also have an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

If several women in a family have ovarian or breast cancer, especially at a young age, this is considered a strong family history. If you have a strong family history of ovarian or breast cancer, you may wish to talk to a genetic counselor. The counselor may suggest genetic testing for you and the women in your family. Genetic tests can sometimes show the presence of specific gene changes that increase the risk of ovarian cancer. - Personal history of cancer: Women who have had cancer of the breast, uterus, colon, or rectum have a higher risk of ovarian cancer.

- Age over 55: Most women are over age 55 when diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

- Never pregnant: Older women who have never been pregnant have an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

- Menopausal hormone therapy: Some studies have suggested that women who take estrogen by itself (estrogen without progesterone) for 10 or more years may have an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

Having a risk factor does not mean that a woman will get ovarian cancer. Most women who have risk factors do not get ovarian cancer. On the other hand, women who do get the disease often have no known risk factors, except for growing older. Women who think they may be at risk of ovarian cancer should talk with their doctor.

Symptoms

Early ovarian cancer may not cause obvious symptoms. But, as the cancer grows, symptoms may include:

- Pressure or pain in the abdomen, pelvis, back, or legs

- A swollen or bloated abdomen

- Nausea, indigestion, gas, constipation, or diarrhea

- Feeling very tired all the time

- Shortness of breath

- Feeling the need to urinate often

- Unusual vaginal bleeding (heavy periods, or bleeding after menopause)

Most often these symptoms are not due to cancer, but only a doctor can tell for sure. Any woman with these symptoms should tell her doctor.

Diagnosis

If you have a symptom that suggests ovarian cancer, your doctor must find out whether it is due to cancer or to some other cause. Your doctor may ask about your personal and family medical history.

You may have one or more of the following tests. Your doctor can explain more about each test:

- Physical exam: Your doctor checks general signs of health. Your doctor may press on your abdomen to check for tumors or an abnormal buildup of fluid (ascites). A sample of fluid can be taken to look for ovarian cancer cells.

- Pelvic exam: Your doctor feels the ovaries and nearby organs for lumps or other changes in their shape or size. A Pap test is part of a normal pelvic exam, but it is not used to collect ovarian cells. The Pap test detects cervical cancer. The Pap test is not used to diagnose ovarian cancer.

- Blood tests: Your doctor may order blood tests. The lab may check the level of several substances, including CA-125. CA-125 is a substance found on the surface of ovarian cancer cells and on some normal tissues. A high CA-125 level could be a sign of cancer or other conditions. The CA-125 test is not used alone to diagnose ovarian cancer. This test is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for monitoring a woman's response to ovarian cancer treatment and for detecting its return after treatment.

- Ultrasound: The ultrasound device uses sound waves that people cannot hear. The device aims sound waves at organs inside the pelvis. The waves bounce off the organs. A computer creates a picture from the echoes. The picture may show an ovarian tumor. For a better view of the ovaries, the device may be inserted into the vagina (transvaginal ultrasound).

- Biopsy: A biopsy is the removal of tissue or fluid to look for cancer cells. Based on the results of the blood tests and ultrasound, your doctor may suggest surgery (a laparotomy) to remove tissue and fluid from the pelvis and abdomen. Surgery is usually needed to diagnose ovarian cancer. To learn more about surgery, see the "Treatment" section.

Although most women have a laparotomy for diagnosis, some women have a procedure known as laparoscopy. The doctor inserts a thin, lighted tube (a laparoscope) through a small incision in the abdomen. Laparoscopy may be used to remove a small, benign cyst or an early ovarian cancer. It may also be used to learn whether cancer has spread.

A pathologist uses a microscope to look for cancer cells in the tissue or fluid. If ovarian cancer cells are found, the pathologist describes the grade of the cells. Grades 1, 2, and 3 describe how abnormal the cancer cells look. Grade 1 cancer cells are not as likely as to grow and spread as Grade 3 cells.

Staging

To plan the best treatment, your doctor needs to know the grade of the tumor (see Diagnosis) and the extent (stage) of the disease. The stage is based on whether the tumor has invaded nearby tissues, whether the cancer has spread, and if so, to what parts of the body.

Usually, surgery is needed before staging can be complete. The surgeon takes many samples of tissue from the pelvis and abdomen to look for cancer.

Your doctor may order tests to find out whether the cancer has spread:

- CT scan: Doctors often use CT scans to make pictures of organs and tissues in the pelvis or abdomen. An x-ray machine linked to a computer takes several pictures. You may receive contrast material by mouth and by injection into your arm or hand. The contrast material helps the organs or tissues show up more clearly. Abdominal fluid or a tumor may show up on the CT scan.

- Chest x-ray: X-rays of the chest can show tumors or fluid.

- Barium enema x-ray: Your doctor may order a series of x-rays of the lower intestine. You are given an enema with a barium solution. The barium outlines the intestine on the x-rays. Areas blocked by cancer may show up on the x-rays.

- Colonoscopy: Your doctor inserts a long, lighted tube into the rectum and colon. This exam can help tell if cancer has spread to the colon or rectum.

These are the stages of ovarian cancer:

- Stage I: Cancer cells are found in one or both ovaries. Cancer cells may be found on the surface of the ovaries or in fluid collected from the abdomen.

- Stage II: Cancer cells have spread from one or both ovaries to other tissues in the pelvis. Cancer cells are found on the fallopian tubes, the uterus, or other tissues in the pelvis. Cancer cells may be found in fluid collected from the abdomen.

- Stage III: Cancer cells have spread to tissues outside the pelvis or to the regional lymph nodes. Cancer cells may be found on the outside of the liver.

- Stage IV: Cancer cells have spread to tissues outside the abdomen and pelvis. Cancer cells may be found inside the liver, in the lungs, or in other organs.

Treatment

Many women with ovarian cancer want to take an active part in making decisions about their medical care. It is natural to want to learn all you can about your disease and treatment choices. Knowing more about ovarian cancer helps many women cope.

Shock and stress after the diagnosis can make it hard to think of everything you want to ask your doctor. It often helps to make a list of questions before an appointment. To help remember what your doctor says, you may take notes or ask whether you may use a tape recorder. You may also want to have a family member or friend with you when you talk to your doctor-to take part in the discussion, to take notes, or just to listen.

You do not need to ask all your questions at once. You will have other chances to ask your doctor or nurse to explain things that are not clear and to ask for more details.

Your doctor may refer you to a gynecologic oncologist, a surgeon who specializes in treating ovarian cancer. Or you may ask for a referral. Other types of doctors who help treat women with ovarian cancer include gynecologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists. You may have a team of doctors and nurses.

Getting a Second Opinion

Before starting treatment, you might want a second opinion about your diagnosis and treatment plan. Many insurance companies cover a second opinion if you or your doctor requests it.It may take some time and effort to gather medical records and arrange to see another doctor. In most cases, a brief delay in starting treatment will not make treatment less effective. To make sure, you should discuss this delay with your doctor. Sometimes women with ovarian cancer need treatment right away.

There are a number of ways to find a doctor for a second opinion:

- Your doctor may refer you to one or more specialists. At cancer centers, several specialists often work together as a team.

- NCI's Cancer Information Service, at 1-800-4-CANCER, can tell you about nearby treatment centers. Information Specialists also can assist you online at LiveHelp (http://www.cancer.gov/livehelp).

- A local or state medical society, a nearby hospital, or a medical school can usually provide the names of specialists.

- NCI provides a helpful fact sheet called "How To Find a Doctor or Treatment Facility If You Have Cancer."

Treatment Methods

Your doctor can describe your treatment choices and the expected results. Most women have surgery and chemotherapy. Rarely, radiation therapy is used.Cancer treatment can affect cancer cells in the pelvis, in the abdomen, or throughout the body:

- Local therapy: Surgery and radiation therapy are local therapies. They remove or destroy ovarian cancer in the pelvis. When ovarian cancer has spread to other parts of the body, local therapy may be used to control the disease in those specific areas.

- Intraperitoneal chemotherapy: Chemotherapy can be given directly into the abdomen and pelvis through a thin tube. The drugs destroy or control cancer in the abdomen and pelvis.

- Systemic chemotherapy: When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein, the drugs enter the bloodstream and destroy or control cancer throughout the body.

You may want to know how treatment may change your normal activities. You and your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your medical and personal needs.

Because cancer treatments often damage healthy cells and tissues, side effects are common. Side effects depend mainly on the type and extent of the treatment. Side effects may not be the same for each woman, and they may change from one treatment session to the next. Before treatment starts, your health care team will explain possible side effects and suggest ways to help you manage them.

You may want to talk to your doctor about taking part in a clinical trial, a research study of new treatment methods. Clinical trials are an important option for women with all stages of ovarian cancer. The section on "The Promise of Cancer Research" has more information about clinical trials.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before your treatment begins:

- What is the stage of my disease? Has the cancer spread from the ovaries? If so, to where?

- What are my treatment choices? Do you recommend intraperitoneal chemotherapy for me? Why?

- Would a clinical trial be appropriate for me?

- Will I need more than one kind of treatment?

- What are the expected benefits of each kind of treatment?

- What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? What can we do to control side effects? Will they go away after treatment ends?

- What can I do to prepare for treatment?

- Will I need to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

- What is the treatment likely to cost? Will my insurance cover the cost?

- How will treatment affect my normal activities?

- Will treatment cause me to go through an early menopause?

- Will I be able to get pregnant and have children after treatment?

- How often should I have checkups after treatment?

Surgery

The surgeon makes a long cut in the wall of the abdomen. This type of surgery is called a laparotomy. If ovarian cancer is found, the surgeon removes:

- both ovaries and fallopian tubes (salpingo-oophorectomy)

- the uterus (hysterectomy)

- the omentum (the thin, fatty pad of tissue that covers the intestines)

- nearby lymph nodes

- samples of tissue from the pelvis and abdomen

If you have early Stage I ovarian cancer, the extent of surgery may depend on whether you want to get pregnant and have children. Some women with very early ovarian cancer may decide with their doctor to have only one ovary, one fallopian tube, and the omentum removed.

You may be uncomfortable for the first few days after surgery. Medicine can help control your pain. Before surgery, you should discuss the plan for pain relief with your doctor or nurse. After surgery, your doctor can adjust the plan if you need more pain relief.

The time it takes to heal after surgery is different for each woman. You will spend several days in the hospital. It may be several weeks before you return to normal activities.

If you haven't gone through menopause yet, surgery may cause hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and night sweats. These symptoms are caused by the sudden loss of female hormones. Talk with your doctor or nurse about your symptoms so that you can develop a treatment plan together. There are drugs and lifestyle changes that can help, and most symptoms go away or lessen with time.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions about surgery:

- What kind of surgery do you recommend for me? Will lymph nodes and other tissues be removed? Why?

- How soon will I know the results from the pathology report? Who will explain them to me?

- How will I feel after surgery?

- If I have pain, how will it be controlled?

- How long will I be in the hospital?

- Will I have any long-term effects because of this surgery?

- Will the surgery affect my sex life?

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses anticancer drugs to kill cancer cells. Most women have chemotherapy for ovarian cancer after surgery. Some women have chemotherapy before surgery.

Usually, more than one drug is given. Drugs for ovarian cancer can be given in different ways:

- By vein (IV): The drugs can be given through a thin tube inserted into a vein.

- By vein and directly into the abdomen: Some women get IV chemotherapy along with intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy. For IP chemotherapy, the drugs are given through a thin tube inserted into the abdomen.

- By mouth: Some drugs for ovarian cancer can be given by mouth.

Chemotherapy is given in cycles. Each treatment period is followed by a rest period. The length of the rest period and the number of cycles depend on the anticancer drugs used.

You may have your treatment in a clinic, at the doctor's office, or at home. Some women may need to stay in the hospital during treatment.

The side effects of chemotherapy depend mainly on which drugs are given and how much. The drugs can harm normal cells that divide rapidly:

- Blood cells: These cells fight infection, help blood to clot, and carry oxygen to all parts of your body. When drugs affect your blood cells, you are more likely to get infections, bruise or bleed easily, and feel very weak and tired. Your health care team checks you for low levels of blood cells. If blood tests show low levels, your health care team can suggest medicines that can help your body make new blood cells.

- Cells in hair roots: Some drugs can cause hair loss. Your hair will grow back, but it may be somewhat different in color and texture.

- Cells that line the digestive tract: Some drugs can cause poor appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or mouth and lip sores. Ask your health care team about medicines that help with these problems.

Some drugs used to treat ovarian cancer can cause hearing loss, kidney damage, joint pain, and tingling or numbness in the hands or feet. Most of these side effects usually go away after treatment ends.

You may find it helpful to read NCI's booklet Chemotherapy and You.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions about chemotherapy:

- When will treatment start? When will it end? How often will I have treatment?

- Which drug or drugs will I have?

- How do the drugs work?

- Do you recommend both IV and IP (intraperitoneal) chemotherapy for me? Why?

- What are the expected benefits of the treatment?

- What are the risks of the treatment? What side effects might I have?

- Can I prevent or treat any of these side effects? How?

- How much will it cost? Will my health insurance pay for all of the treatment?

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses high-energy rays to kill cancer cells. A large machine directs radiation at the body.Radiation therapy is rarely used in the initial treatment of ovarian cancer, but it may be used to relieve pain and other problems caused by the disease. The treatment is given at a hospital or clinic. Each treatment takes only a few minutes.

Side effects depend mainly on the amount of radiation given and the part of your body that is treated. Radiation therapy to your abdomen and pelvis may cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or bloody stools. Also, your skin in the treated area may become red, dry, and tender. Although the side effects can be distressing, your doctor can usually treat or control them. Also, they gradually go away after treatment ends.

NCI provides a booklet called Radiation Therapy and You.

Supportive Care

Ovarian cancer and its treatment can lead to other health problems. You may receive supportive care to prevent or control these problems and to improve your comfort and quality of life.

Your health care team can help you with the following problems:

- Pain: Your doctor or a specialist in pain control can suggest ways to relieve or reduce pain. You may want to read the NCI booklet Pain Control.

- Swollen abdomen (from abnormal fluid buildup called ascites): The swelling can be uncomfortable. Your health care team can remove the fluid whenever it builds up.

- Blocked intestine: Cancer can block the intestine. Your doctor may be able to open the blockage with surgery.

- Swollen legs (from lymphedema): Swollen legs can be uncomfortable and hard to bend. You may find exercises, massages, or compression bandages helpful. Physical therapists trained to manage lymphedema can also help.

- Shortness of breath: Advanced cancer can cause fluid to collect around the lungs. The fluid can make it hard to breathe. Your health care team can remove the fluid whenever it builds up.

- Sadness: It is normal to feel sad after a diagnosis of a serious illness. Some people find it helpful to talk about their feelings. See the "Sources of Support" section for more information.

You can get information about supportive care on NCI's Web site at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/coping and from NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER or LiveHelp (http://www.cancer.gov/livehelp).

Nutrition and Physical Activity

It's important for women with ovarian cancer to take care of themselves. Taking care of yourself includes eating well and staying as active as you can.

You need the right amount of calories to maintain a good weight. You also need enough protein to keep up your strength. Eating well may help you feel better and have more energy.

Sometimes, especially during or soon after treatment, you may not feel like eating. You may be uncomfortable or tired. You may find that foods do not taste as good as they used to. In addition, the side effects of treatment (such as poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, or mouth sores) can make it hard to eat well. Your doctor, a registered dietitian, or another health care provider can suggest ways to deal with these problems. Also, the NCI booklet Eating Hints has many useful ideas and recipes.

Many women find they feel better when they stay active. Walking, yoga, swimming, and other activities can keep you strong and increase your energy. Whatever physical activity you choose, be sure to talk to your doctor before you start. Also, if your activity causes you pain or other problems, be sure to let your doctor or nurse know about it.

Follow-up Care

You will need regular checkups after treatment for ovarian cancer. Even when there are no longer any signs of cancer, the disease sometimes returns because undetected cancer cells remained somewhere in your body after treatment.

Checkups help ensure that any changes in your health are noted and treated if needed. Checkups may include a pelvic exam, a CA-125 test, other blood tests, and imaging exams.

If you have any health problems between checkups, you should contact your doctor.

You may wish to read the NCI booklet Facing Forward: Life After Cancer Treatment. It answers questions about follow-up care and other concerns. It also suggests ways to talk with your doctor about making a plan of action for recovery and future health.

Complementary Medicine

It's natural to want to help yourself feel better. Some people with cancer say that complementary medicine helps them feel better. An approach is called complementary medicine when it is used along with standard cancer treatment. Acupuncture, massage therapy, herbal products, vitamins or special diets, and meditation are examples of such approaches.

Talk with your doctor if you are thinking about trying anything new. Things that seem safe, such as certain herbal teas, may change the way your cancer treatment works. These changes could be harmful. And certain complementary approaches could be harmful even if used alone.

You may find it helpful to read the NCI booklet Thinking About Complementary & Alternative Medicine: A Guide for People with Cancer.

You also may request materials from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, which is part of the National Institutes of Health. You can reach their clearinghouse at 1-888-644-6226 (voice) and 1-866-464-3615 (TTY). Also, you can visit their Web site at http://www.nccam.nih.gov.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before you decide to use complementary medicine:

- What benefits can I expect from this approach?

- What are its risks?

- Do the expected benefits outweigh the risks?

- What side effects should I watch for?

- Will the approach change the way my cancer treatment works? Could this be harmful?

- Is this approach under study in a clinical trial?

- How much will it cost? Will my health insurance pay for this approach?

- Can you refer me to a complementary medicine practitioner?

Sources of Support

Learning you have ovarian cancer can change your life and the lives of those close to you. These changes can be hard to handle. It is normal for you, your family, and your friends to have many different and sometimes confusing feelings.

You may worry about caring for your family, keeping your job, or continuing daily activities. Concerns about treatments and managing side effects, hospital stays, and medical bills are also common. Doctors, nurses, and other members of your health care team can answer questions about treatment, working, and other activities. Meeting with a social worker, counselor, or member of the clergy can be helpful if you want to talk about your feelings or concerns. Often, a social worker can suggest resources for financial aid, transportation, home care, or emotional support.

Support groups also can help. In these groups, patients or their family members meet with other patients or their families to share what they have learned about coping with the disease and the effects of treatment. Groups may offer support in person, over the telephone, or on the Internet. You may want to talk with a member of your health care team about finding a support group.

It is natural for you to be worried about the effects of ovarian cancer and its treatment on your sexuality. You may want to talk with your doctor about possible sexual side effects and whether these effects will be permanent. Whatever happens, it may be helpful for you and your partner to talk about your feelings and help one another find ways to share intimacy during and after treatment.

For tips on coping, you may want to read the NCI booklet Taking Time: Support for People With Cancer. NCI's Information Specialists at 1-800-4-CANCER and at LiveHelp (http://www.cancer.gov/livehelp) can help you locate programs, services, and publications. They can send you a list of organizations that offer services to women with cancer.

The Promise of Cancer Research

Doctors all over the country are conducting many types of clinical trials (research studies in which people volunteer to take part). They are studying new and better ways to prevent, detect, and treat ovarian cancer.

Clinical trials are designed to answer important questions and to find out whether new approaches are safe and effective. Research already has led to advances, and researchers continue to search for more effective methods.

Women who join clinical trials may be among the first to benefit if a new approach is effective. And even if the women in a trial do not benefit directly, they may still make an important contribution by helping doctors learn more about ovarian cancer and how to control it. Although clinical trials may pose some risks, researchers do all they can to protect their patients.

Researchers are conducting studies with women across the country:

- Prevention studies: For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer, the risk of developing the disease may be reduced by removing the ovaries before cancer is detected. This surgery is called prophylactic oophorectomy. Women who are at high risk of ovarian cancer are taking part in trials to study the benefits and harms of this surgery. Other doctors are studying whether certain drugs can help prevent ovarian cancer in women at high risk.

- Screening studies: Researchers are studying ways to find ovarian cancer in women who do not have symptoms.

- Treatment studies: Doctors are testing novel drugs and new combinations. They are studying biological therapies, such as monoclonal antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies can bind to cancer cells. They interfere with cancer cell growth and the spread of cancer.

If you are interested in being part of a clinical trial, talk with your doctor. You may want to read the NCI booklet Taking Part in Cancer Treatment Research Studies. It explains how clinical trials are carried out and explains their possible benefits and risks.

NCI's Web site includes a section on clinical trials at http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials. It has general information about clinical trials as well as detailed information about specific ongoing studies of ovarian cancer. NCI's Information Specialists at 1-800-4-CANCER and at LiveHelp (http://www.cancer.gov/livehelp) can answer questions and provide information about clinical trials.