12

Co-Lead Agencies: | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

[Note: The National Library of Medicine has provided PubMed links to available references that appear at the end of this focus area document.]

Contents

Interim Progress Toward Year 2000 Objectives

Healthy People 2010—Summary of Objectives

Healthy People 2010 Objectives

Related Objectives From Other Focus Areas

Improve cardiovascular health and quality of life through the prevention, detection, and treatment of risk factors; early identification and treatment of heart attacks and strokes; and prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death for all people in the United States. Stroke is the third leading cause of death. Heart disease and stroke continue to be major causes of disability and significant contributors to increases in health care costs in the United States.[1]

Epidemiologic and statistical studies have identified a number of factors that increase the risk of heart disease and stroke. In addition, clinical trials and prevention research studies have demonstrated effective strategies to prevent and control these risk factors and thereby reduce illnesses, disabilities, and deaths caused by heart disease and stroke.

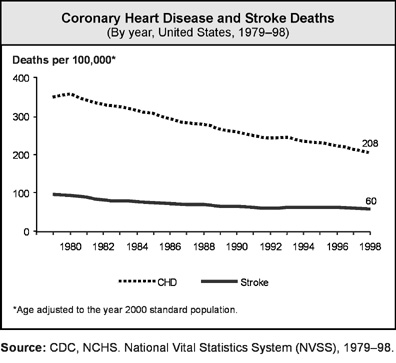

Coronary heart disease (CHD) accounts for the largest proportion of heart disease. About 12 million people in the United States have CHD.1 The CHD death rate peaked in the mid-1960s and has declined in the general population over the past 35 years. This decline began in females in the 1950s and in males in the 1960s. Although absolute declines have been much greater in males than in females, rates of decline also have been greater in males, but in recent years they have been greater in females.

Since 1950, there has been a clear rise and fall in CHD death rates for each racial and gender group. Although the age-adjusted death rate for CHD continues to decline each year, declines in the unadjusted death rate and in the number of deaths have slowed because of an increase in the number of older people in the United States, who have higher rates of CHD.

High blood cholesterol is a major risk factor for CHD that can be modified. More than 50 million U.S. adults have blood cholesterol levels that require medical advice and treatment.[2] More than 90 million adults have cholesterol levels that are higher than desirable. Experts recommend that all adults aged 20 years and older have their cholesterol levels checked at least once every 5 years to help them take action to prevent or lower their risk of CHD.[3] Lifestyle changes that prevent or lower high blood cholesterol include eating a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol, increasing physical activity, and reducing excess weight.3

About 4 million persons have cerebrovascular disease,1 a major form of which is stroke. About 600,000 strokes occur each year in the United States, resulting in about 158,000 deaths. Death rates for stroke are highest in the southeastern United States. Like CHD death rates, stroke death rates have declined over the past 30 years. The decline accelerated in the 1970s for whites and African Americans. The rate of decline, however, has slowed in recent years. The overall decline has occurred mainly because of improvements in the detection and treatment of high blood pressure (hypertension).

High blood pressure is known as the “silent killer” and remains a major risk factor for CHD, stroke, and heart failure. About 50 million adults in the United States have high blood pressure. High blood pressure also is more common in older persons. Comparing the 1976–80 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II) and the 1988–91 survey (NHANES III, phase 1) reveals an increase from 51 to 73 percent in the proportion of persons who were aware that they had high blood pressure.[4], [5] Nevertheless, a large proportion of persons with high blood pressure still are unaware that they have this disorder.4, 5

The age composition of the U.S. population changed dramatically during the 20th century and will continue to change during the 21st century. By the end of the 1990s, one in every four persons was aged 50 years or older. By 2030, about one in three will be aged 50 years or older. Most significant has been the increase in the size of the population aged 65 years and older. In addition, the percentage of persons aged 85 years and older has increased significantly. Heart disease and stroke deaths rise significantly after age 65 years, accounting for more than 40 percent of all deaths among persons aged 65 to 74 years and almost 60 percent of those aged 85 years and older. In the 1980s and 1990s, heart failure emerged as a major chronic disease for older adults.[6], [7], [8], [9] Almost 75 percent of the nearly 5 million patients with heart failure in the United States are older than 65 years.8 Hospitalization rates for heart failure continue to increase significantly in those aged 65 years and older.9

Atrial fibrillation (AF) affects close to 2 million people in the United States. The number of existing cases of AF increases with age and is more common in males than in females.[10] Even though prevalence of AF is greater in males than in females, the absolute number of males and females with AF is about equal. About 70 percent of persons with AF are between age 65 and 85 years. About 15 percent of strokes occur in persons with AF.10 Because females have a longer life expectancy than males, the actual number of cases in elderly females (older than 75 years) is greater than in elderly males. Cases of AF may continue to rise as persons live longer and as more persons survive a first heart attack.

Because national data systems will not be available in the first half of the decade for tracking progress, two subjects of interest are not addressed in this focus area’s objectives. Representing a research and data collection agenda for the coming decade, the topics are related to provider counseling and increasing awareness of cardiovascular disease (CVD) as the leading cause of death for all females. The first topic coversinstruction of high-risk patients and family members or significant others in preparing appropriate heart attack and stroke action plans for seeking rapid emergency care, including when to call 911 or the local emergency number. The second topic deals with increasing awareness among all females that CVD is their leading cause of death.

In general, the heart disease death rate has been consistently higher in males than in females and higher in the African American population than in the white population. In addition, over the past 30 years the CHD death rate has declined differentially by gender and race. In the 1970s, African American females experienced the greatest decline in CHD. This steep decline leveled off in the 1980s, when rates of decline for white males and females exceeded those for African American males and females, and African American females had the lowest rate of decline.[11] In the 1980s, males had a steeper rate of decline than females. Between 1980 and 1995, the percentage declines were greater in males than in females and greater in whites than in African Americans. In 1995, the age-adjusted death rate for heart disease was 42 percent higher in African American males than in white males, 65 percent higher in African American females than in white females, and almost twice as high in males as in females.

Disparities also exist in treatment outcomes for patients who have heart attacks. Females, in general, have poorer outcomes following a heart attack than do males: 44 percent of females who have a heart attack die within a year, compared with 27 percent of males. At older ages, females who have a heart attack are twice as likely as males to die within a few weeks.[12] These differences are explained, in part, by the presence of coexisting conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and congestive heart failure. After controlling for such factors, however, studies indicate an association remains between female gender and death following a heart attack. Complications are more frequent in females than in males after coronary intervention procedures, such as angioplasty or bypass surgery, are performed. Additional studies are needed to evaluate specific interventions and determine whether gender-specific interventions may be beneficial. In general, factors such as age (older), gender (female), race or ethnicity, low socioeconomic status, and prior medical conditions (previous heart attack, history of angina or diabetes) have been associated with longer prehospital delays in seeking care for symptoms of a heart attack.[13]

The male-female disparity in stroke deaths widened from the 1970s until the 1980s and then narrowed. Although stroke death rates have been decreasing, the decline among African Americans has not been as substantial as the decline in the total population. The racial differences in the number of new cases of stroke and deaths due to stroke are even greater than those found in CHD. Stroke deaths are highest in African American females born before 1950 and in African American males born after 1950. Among the racial and gender groups, declines in the stroke death rate are smallest in African American males. When adjusted for age, stroke deaths are almost 80 percent higher in African Americans than in whites and about 17 percent higher in males than in females. Moreover, age-specific stroke deaths are higher in African Americans than in whites in all age groups up to age 84 years and higher in males than in females throughout all adult age groups.

The number of existing cases of high blood pressure is nearly 40 percent higher in African Americans than in whites (an estimated 6.4 million African Americans have high blood pressure),[14] and its effects are more frequent and severe in the African American population.

Other racial and ethnic CHD and stroke data indicate that among U.S. adults aged 20 years and older, the age-adjusted (year 2000) prevalence of heart attacks is 5.2 percent for non-Hispanic white males and 2.0 percent for females; 4.3 percent for non-Hispanic black males and 3.3 percent for females; 4.1 percent for Mexican American males and 1.9 percent for females. Among American Indians aged 65 to 74 years the rates (per 1,000) of new and recurrent heart attacks are 25.1 for males and 9.1 for females. The average annual CHD incidence rate (per 1,000) in Japanese American males living in Hawaii was 4.6 for ages 45 to 49 years, 6.0 for ages 50 to 54 years, 7.2 for ages 55 to 59 years, 8.8 for ages 60 to 64 years, and 10.5 for ages 65 to 68 years.10

For stroke, other data show that the estimated age-adjusted (2000 standard) prevalence of stroke for persons aged 20 years and older in the United States was 2.2 percent for non-Hispanic white males and 1.5 percent for females; for non-Hispanic blacks, 2.5 percent for males and 3.2 percent for females; and for Mexican Americans, 2.3 percent for males and 1.3 percent for females. The rates (per 1,000) of new and recurrent strokes in American Indians aged 65 to 74 years are 15.2 for males and 7.9 for females. The average annual incidence rates (per 1,000) of stroke in Japanese American males increased with advancing age from 45 to 49 years to 65 to 68 years at the initial examination: 2.1 to 8.2 for total stroke, 1.5 to 6.6 for thromboembolic stroke, and 0.4 to 1.0 for intracerebral hemorrhage.10

Primary prevention. Heart disease and stroke share several risk factors, including high blood pressure, cigarette smoking, high blood cholesterol, and overweight. Physical inactivity and diabetes are additional risk factors for heart disease. (See Focus Area 5. Diabetes.) The lifetime risk for developing CHD is very high in the United States: one of every two males and one of every three females aged 40 years and under will develop CHD sometime in their life. Primary prevention, specifically through lifestyle interventions that promote heart-healthy behaviors, is a major strategy to reduce the development of heart disease or stroke.[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]

A number of studies have shown that lifestyle interventions can help prevent high blood pressure and reduce blood cholesterol levels. For high blood pressure, these interventions include increasing the level of aerobic physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, limiting the consumption of alcohol to moderate levels for those who drink, reducing salt and sodium intake, and eating a reduced-fat diet high in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy food. Moreover, studies show that a diet low in saturated fat, dietary cholesterol, and total fat—with physical activity and weight control—can lower blood cholesterol levels.[20], [21], [22]

Overweight and obesity are growing public health problems, affecting adults, adolescents, and children. Overweight and obesity affect a large proportion of the U.S. population—55 percent of adults. These persons are at increased risk of illness from high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol and other lipid disorders, type 2 diabetes, CHD, stroke, and other diseases. Efforts to prevent overweight and obesity by promoting heart-healthy behaviors—beginning in childhood—are needed to help reverse the trend. Balancing calorie intake with physical activity is critical. Research in the 1990s showed that a wide range of physical activities are beneficial to health and that everyone can benefit from physical activity. Even when physical activity is less than vigorous, it can still produce health benefits, including a decreased risk of CHD.[23], [24], [25], [26] (See Focus Area 19. Nutrition and Overweight.)

Nonetheless, increasing the level of physical activity remains a challenge. Furthermore, according to the 1996 surgeon general’s report on physical activity and health,[27] the percentage of people who say they engage in no leisure-time physical activity is higher among females than males, among African Americans and Hispanics than whites, among older adults than younger adults, and among the less affluent than the more affluent. (See Focus Area 22. Physical Activity and Fitness.)

Progress on smoking cessation will play a critical role in achieving the Healthy People 2010 objective for heart disease reduction. Smoking cessation has major and immediate health benefits for men and women of all ages. For example, people who quit smoking before age 50 years have half the risk of dying in the next 15 years, compared with people who continue to smoke.[28]

Studies have shown that risk factors for heart disease and stroke develop early in life: atherosclerosis already is present in late adolescence, diabetes in overweight children is on the rise, and hypertension can begin in the early teens.[29], [30] Tobacco use also begins in adolescence; therefore, primary prevention efforts should be expanded in elementary and secondary schools and at the college level. Nationwide mass media campaigns, community-based programs, and other communication efforts should be expanded to give groups better access to information and programs. These programs should promote heart-healthy behaviors at the community level as well as detect and treat existing risk factors.

Risk factor detection and treatment. Screening for risk factors, particularly for high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol, is an important step in identifying individuals whose risk factors may be undiagnosed and referring them to ongoing care. A host of studies has shown that dietary and pharmacologic therapy can reduce CHD and stroke risk factors, especially high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol. These interventions, coupled with other lifestyle changes, such as stopping smoking, increasing physical activity, and maintaining a healthy weight, can be even more effective in lowering the risk of a heart attack or stroke.[31], [32], [33], [34]

Research showing the importance of blood pressure to health led to the introduction by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program (NHBPEP) in 1972.[35] NHBPEP is the first large-scale public outreach and education campaign to reduce high blood pressure. Its promotion of the detection, treatment, and control of high blood pressure has been credited with influencing the dramatic increase in the public’s understanding of hypertension and its role in heart attacks and strokes, as well as related declines in deaths. The percentage of people who were able to control their high blood pressure through lifestyle changes and through antihypertensive drug therapy rose from about 16 percent in 1971–72 to about 65 percent in 1988–94.1 About 90 percent of all adults now have their blood pressure measured at least once every 2 years. Average blood pressure levels have fallen by 10 to 12 mmHg since the advent of NHBPEP.[36] A slowly changing issue has been the recognition of systolic blood pressure as a more important predictor of CHD than diastolic blood pressure, especially in older adults.[37], [38]

Research reported in the 1980s showed for the first time that lowering high blood cholesterol significantly reduces the risk for heart attacks and heart attack deaths. This research led to the creation of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) in 1985.[39] Clinical trials have proved that lowering cholesterol in persons with and without existing CHD reduces illness and death from CHD and even reduces overall death rates. Since NCEP was launched, the percentage of persons who have had their cholesterol checked has more than doubled, from 35 percent in 1983 to 75 percent in 1995.[40] Consumption of saturated fat, total fat, and cholesterol declined during the 1980s and 1990s, average blood cholesterol levels in adults dropped from 213 mg/dL in 1978 to 203 mg/dL in 1991 (age adjusted to 1980 population), and the prevalence of high blood cholesterol requiring medical advice and treatment fell from 36 percent to 29 percent.39 These results reflect the impact of NCEP’s population and high-risk strategies for lowering cholesterol.

The NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative, in cooperation with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, released in 1998 the first Federal guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults.[41] These clinical practice guidelines are designed to help physicians in their identification and treatment of overweight and obesity, a growing public health problem. Persons who are overweight or obese are at increased risk of illness from high blood pressure, lipid disorders, type 2 diabetes, CHD, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea and other respiratory problems, and certain cancers. The total cost attributable to obesity-related diseases in the United States is nearly $100 billion annually. The guidelines present a new approach to the assessment of overweight and obesity and establish principles of safe and effective weight loss. According to the guidelines, the assessment of overweight involves three key measures—body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and risk factors for diseases and conditions associated with obesity. The definitions in the guidelines are based on research that relates body mass index to the risk of death and illness, with overweight defined as a BMI of 25 to 29.9 and obesity as a BMI of 30 and above.41

As BMI levels rise, the average blood pressure and total cholesterol levels increase, and average high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (good cholesterol) levels decrease. Males in the highest obesity category have more than twice the risk of high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, or both, compared to males of normal weight. Females in the highest obesity category have four times the risk of either or both of these risk factors, compared to normal weight females. Therefore, the guidelines recommend weight loss to reduce high total cholesterol, raise low levels of HDL, reduce high blood pressure, and reduce elevated blood glucose in overweight persons who have two or more risk factors and in obese persons. Overweight persons without other risk factors are advised to prevent further weight gain.

The clinical practice guideline on smoking cessation issued by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) clearly shows that a variety of interventions are effective and concludes that improvements in cessation will require active participation of health care systems.[42]

These national education efforts have changed the way people think about their health. More people than ever are having their blood pressure and their cholesterol levels checked and are taking action to keep them under control. Individuals are aware of preventive measures and health promotion behaviors that can reduce their risk of developing CHD- and stroke-related illnesses. In addition, improved pharmacologic therapies are available to treat and control major CHD risk factors, such as high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, and obesity. These therapies however, may be underutilized by health care providers.

Early identification and treatment. Each year in the United States, about 1.1 million persons experience a heart attack (acute myocardial infarction [AMI]). In 1996, 476,000 persons died from heart attacks—about 51 percent were males and 49 percent were females. More than half of these deaths occurred suddenly, within 1 hour of symptom onset, outside the hospital.1, [43] For those patients who survive a heart attack, delay in treatment can mean increased damage to the heart muscle and poorer outcomes.

The benefits of rapid identification and treatment of heart attacks are clear. Early treatment of heart attack patients reduces heart-muscle damage, improves heart muscle function, and lowers the heart attack death rate.[44], [45]

Controlled trials of clot-dissolving (thrombolytic) agents used during the acute phase of a heart attack have demonstrated the benefits of opening the affected coronary artery and reestablishing blood flow. The results from these trials have been incorporated into the current treatment model for early intervention during the acute phase of a heart attack.44 Patients who receive clot-dissolving agents in the first and second hours after the onset of heart attack symptoms experience significant reductions in disability and death when compared to patients who are treated in the third to sixth hours.[46] Even patients who are treated between 6 and 12 hours after the onset of symptoms show modest but significant benefits when compared to patients whose treatment is delayed more than 12 hours.[47] Other acute interventions for heart attack patients include balloon angioplasty, coronary stenting, and coronary artery bypass surgery.45, [48] The importance of early treatment has generated a growing interest in detecting the earliest warning, or “prodromal,” symptoms of a heart attack, thus providing the lead time needed to treat heart attack patients as quickly and effectively as possible.[49]

As with heart attacks, deaths from stroke can be reduced or delayed by preventing and controlling risk factors and using the most effective therapies in a timely manner. Functional limitations can be minimized when patients are treated with clot-dissolving therapy within 3 hours of a thrombotic stroke.[50] As therapies have become increasingly more effective, delays in treatment initiation and lack of implementation of therapies pose major barriers to improving outcomes. Thus far, efforts to provide appropriate access to timely and optimal care to patients with acute coronary syndromes and thrombotic stroke generally are not organized into a unified, cohesive system in communities across the United States.[51]

Early access to emergency health care services is also a critical determinant of outcome for victims of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. For out-of-hospital cardiac arrest where bystanders are present, a key factor is minimizing the time from the moment the collapse is recognized to the delivery of a short burst of electrical current. Collapse recognition occurs when a bystander notices that the affected individual is unresponsive, has slowed or stopped breathing, or lacks a detectable pulse.51 As soon as the emergency is recognized, the bystander should call 911 or the local emergency number. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is critical and should begin immediately. The sooner CPR and defibrillation are given to a person in cardiac arrest or ventilation is given for respiratory arrest, the greater the chances of survival.[52] (See Focus Area 1. Access to Quality Health Services.)

Despite evidence that effective treatment depends on rapid response to the patient, only a minority of individuals who can benefit from defibrillatory shock or thrombolytic agents are treated early enough for them to work.[53] The public health challenge is to develop and maintain programs for easier identification and treatment of individuals with AMI and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Counseling by health care providers could help to increase awareness of the symptoms and signs of a heart attack or stroke and the appropriate actions to take, such as accessing emergency medical services. It also can help reduce and control factors that increase the risk of a heart attack or a stroke. To focus resources where they might derive the greatest benefit, education should be, at a minimum, aimed at reducing delays in seeking treatment for those individuals who are at high risk for a future cardiovascular event—for example, those with existing CHD and multiple CHD risk factors.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) recurrence. Patients with CHD, atherosclerotic disease of the aorta or peripheral arteries, or carotid artery disease are at high risk for heart attack and CHD death.[54], [55] About 50 percent of all heart attacks and at least 70 percent of CHD deaths occur in individuals with prior symptoms of CVD.[56], [57] The risk for heart attack and death among persons with established CHD (or other atherosclerotic disease) is five to seven times higher than among the general population.3

Risk factor control can greatly reduce the risk of subsequent cardiovascular problems in patients with CHD. For example, clinical trials have proved that lowering low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels in CHD patients dramatically reduces heart attacks, CHD and CVD deaths, and total deaths.[58], [59], [60] Clinical trials have also demonstrated that lowering blood pressure in such patients reduces CVD endpoints (such as heart disease, stroke, heart attacks, and coronary artery disease) and deaths from all causes.[61], [62], [63] Adequate control of risk factors in the 12 million adults with CHD could reduce the overall rate of heart attacks and CHD deaths in the United States by over 20 percent. Many CHD patients, however, are not getting the aggressive risk factor management they need.

Clinical trials also show that therapeutic interventions can relieve symptoms, reduce deaths, reduce the number of rehospitalizations, and improve the quality of life for older adults with heart failure. Despite the development and promotion of clinical practice guidelines, physicians are continuing to underutilize recommended therapies. As the number of older adults who experience heart failure rises (expected to double by about 2040), these guidelines will need to be incorporated into clinical practice.[64], [65]

Adherence and compliance. There currently exist a number of well-established recommendations for preventing and treating cardiovascular disease and its associated risk factors.[66], [67], [68] However, the potential benefits to be gained from applying these science-based recommendations often are not realized because of the multiple factors involved in adherence to such recommendations. The ability or willingness of the patient to carry out a treatment program successfully is of critical importance.

Experience with the long-term management of asymptomatic CHD risk factors such as hypertension indicates that a sizable number of patients do not successfully carry out their prescribed treatment regimen. The reasons vary: the patient may choose not to have the initial prescription filled, may successfully initiate therapy only to abandon it after a few weeks or months, or may comply with only part of the regimen and thus fail to achieve optimal control. Continued efforts are needed to better understand the determinants of adherence to ensure that patients stay with their prescribed therapy.[69], [70] Also, health care providers and the health care systems in which they work are critical factors in determining whether established interventions are prescribed and patients adequately educated and monitored for therapeutic response.[71], [72] Finally, support from the patient’s community and greater use of technology such as the Internet also have an increasingly important role in promoting long-term adherence to lifestyle and pharmacologic regimens. Achieving long-term control of CHD risk factors requires that the same interest and attention given to initial evaluation and treatment decisions also be given to long-term management issues.

Future efforts. Population studies and public outreach are two of the most important areas of future research. Advanced technology allows researchers to screen persons noninvasively and painlessly for signs of developing atherosclerosis. Eventually, when their role in medical practice has been better delineated, noninvasive methods (such as magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound) may be used to determine the number of persons in the population who have heart disease or are at risk of developing heart disease.

Many people know what a desirable cholesterol level is, what their blood pressure should be, and that these factors relate to a risk of heart disease and stroke. The average person can expect to live 5.5 years longer today than he or she did 30 years ago, and nearly 4 years of that gain in life expectancy can be attributed to progress against CVD, including CHD and stroke. However, much remains to be done to ensure that all segments of the population share in these benefits. Although national health data on African Americans and Hispanics have been collected since the early 1980s, data on heart disease and stroke risk factors are sparse for other population groups, including American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, Asians, and Pacific Islanders. Adequate national data on all these populations will enable researchers to examine racial and ethnic differences more fully.

Public outreach and community health intervention efforts, such as those that encourage persons to lower their high blood pressure or to get their cholesterol checked or to help people stop smoking, are important parts of health care in the United States. Culturally and linguistically appropriate counseling by health care providers is important to those efforts. New coalitions between health care providers and individual communities are forming to focus on the prevention and management of chronic CVD throughout all stages of life. Emerging areas of research include the effect of socioeconomic status on health and access to care; health status in rural populations, which often have low income and education levels; and quality of life as a criterion for evaluating treatment. With the knowledge gained through these efforts, communities will be able to use well-tested health promotion, disease prevention, and early management strategies to lower their costs and begin to extend the benefits of improved health to all persons in the United States.[73]

Extensive progress has been made in reducing deaths from and risk factors for heart disease and stroke, but significant challenges remain. Between 1987 and 1996, the age-adjusted death rate for CHD declined by 22.2 percent, and for stroke, it declined by 13.2 percent. Despite these achievements, the Healthy People 2000 objectives on CHD and stroke did not reach the year 2000 targets, and the disparities between African Americans and whites were not reduced.

However, progress occurred in reducing high blood cholesterol and controlling high blood pressure. Average total cholesterol declined from 213 mg/dL in 1976–80 to 203 mg/dL in 1988–94, and the prevalence of high blood cholesterol declined from 26 percent to 19 percent, thereby achieving the year 2000 target. In the same time period, control rates among persons who have high blood pressure increased from 11 percent to 29 percent. However, levels fell short of year 2000 targets. The age-adjusted prevalence of overweight or obesity increased from 26 percent in 1976–80 to 35 percent in 1988–94.

The percentage of the population who engaged in light to moderate physical activity remained stable at around 22 percent between 1985 and 1995. Caloric intake from fat as a percentage of total calories consumed declined from 36 percent in 1976–80 to 34 percent in 1988–94, but fell short of the target of 30 percent. Smoking among adults declined steadily from the mid-1960s through the late 1980s, and has leveled off in the 1990s. In 1998, median adult smoking prevalence for all 50 States and the District of Columbia was 22.9 percent—25.3 percent for men and 21.0 percent for women.73

Note: Unless otherwise noted, data are from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Healthy People 2000 Review, 1998–99.

Heart Disease and Stroke

Goal: Improve cardiovascular health and quality of life through the prevention, detection, and treatment of risk factors; early identification and treatment of heart attacks and strokes; and prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events.

|

Number |

Objective Short Title |

|

|

Heart Disease |

||

|

12-1 |

Coronary heart disease (CHD) deaths |

|

|

12-2 |

Knowledge of symptoms of heart attack

and importance |

|

|

12-3 |

Artery-opening therapy |

|

|

12-4 |

Bystander response to cardiac arrest |

|

|

12-5 |

Out-of-hospital emergency care |

|

|

12-6 |

Heart failure hospitalizations |

|

|

Stroke |

||

|

12-7 |

Stroke deaths |

|

|

12-8 |

Knowledge of early warning symptoms of stroke |

|

|

Blood Pressure |

||

|

12-9 |

High blood pressure |

|

|

12-10 |

High blood pressure control |

|

|

12-11 |

Action to help control blood pressure |

|

|

12-12 |

Blood pressure monitoring |

|

|

Cholesterol |

||

|

12-13 |

Mean total blood cholesterol levels |

|

|

12-14 |

High blood cholesterol levels |

|

|

12-15 |

Blood cholesterol screening |

|

|

12-16 |

LDL-cholesterol level in CHD patients |

|

12-1. | Reduce coronary heart disease deaths. |

Target: 166 deaths per 100,000 population.

Baseline: 208 coronary heart disease deaths per 100,000 population in 1998 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting method: 20 percent improvement.

Data source: National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), CDC, NCHS.

|

Total Population, 1998 |

Coronary Heart Disease Deaths |

|

Rate per 100,000 |

|

|

TOTAL |

208 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

126 |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

123 |

|

Asian |

DNC |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

DNC |

|

Black or African American |

252 |

|

White |

206 |

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino |

145 |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

211 |

|

Black or African American |

257 |

|

White |

208 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

165 |

|

Male |

265 |

|

Education level (aged 25 to 64 years) |

|

|

Less than high school |

96 |

|

High school graduate |

80 |

|

At least some college |

38 |

|

Disability status |

|

|

Persons with disabilities |

DNC |

|

Persons without disabilities |

DNC |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

12-2. | (Developmental) Increase the proportion of adults aged 20 years and older who are aware of the early warning symptoms and signs of a heart attack and the importance of accessing rapid emergency care by calling 911. |

Potential data source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

12-3. | (Developmental) Increase the proportion of eligible patients with heart attacks who receive artery-opening therapy within an hour of symptom onset. |

Potential data source: National Registry of Myocardial Infarction, National Acute Myocardial Infarction Project, HCFA.

12-4. | (Developmental) Increase the proportion of adults aged 20 years and older who call 911 and administer cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) when they witness an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. |

Potential data source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

12-5. | (Developmental) Increase the proportion of eligible persons with witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who receive their first therapeutic electrical shock within 6 minutes after collapse recognition. |

Potential data source: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), AHRQ.

12-6. | Reduce hospitalizations of older adults with congestive heart failure as the principal diagnosis. |

Target and baseline:

|

Objective |

Reduction in Hospitalizations of Older Adults With Congestive Heart Failure as the Principal Diagnosis |

1997 |

2010 |

|

Per 1,000 Population |

|||

|

12-6a. |

Adults aged 65 to 74 years |

13.2 |

6.5 |

|

12-6b. |

Adults aged 75 to 84 years |

26.7 |

13.5 |

|

12-6c. |

Adults aged 85 years and older |

52.7 |

26.5 |

Target setting method: Better than the best.

Data source: National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults With Congestive Heart Failure as Principal Diagnosis, 1997 |

Heart Failure Hospitalizations |

||

|

12-6a. |

12-6b. |

12-6c. |

|

|

Rate per 1,000 |

|||

|

TOTAL |

13.2 |

26.7 |

52.7 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|||

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

DSU |

DSU |

DSU |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

DSU |

DSU |

DSU |

|

Asian |

DNC |

DNC |

DNC |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

DNC |

DNC |

DNC |

|

Black or African American |

20.0 |

21.4 |

47.0 |

|

White |

9.9 |

21.4 |

41.8 |

|

|

|||

|

Hispanic or Latino |

DSU |

DSU |

DSU |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

DSU |

DSU |

DSU |

|

Black or African American |

DSU |

DSU |

DSU |

|

White |

DSU |

DSU |

DSU |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Female |

11.5 |

25.0 |

50.2 |

|

Male |

15.3 |

29.2 |

58.8 |

|

Education level |

|||

|

Less than high school |

DNC |

DNC |

DNC |

|

High school graduate |

DNC |

DNC |

DNC |

|

At least some college |

DNC |

DNC |

DNC |

|

Disability status |

|||

|

People with disabilities |

DNC |

DNC |

DNC |

|

People without disabilities |

DNC |

DNC |

DNC |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

12-7. | Reduce stroke deaths. |

Target: 48 deaths per 100,000 population.

Baseline: 60 deaths from stroke per 100,000 population occurred in 1998 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting method: 20 percent improvement.

Data source: National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), CDC, NCHS.

|

Total Population, 1998 |

Stroke Deaths |

|

Rate per 100,000 |

|

|

TOTAL |

60 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

38 |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

51 |

|

Asian |

DNC |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

DNC |

|

Black or African American |

80 |

|

White |

58 |

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino |

39 |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

60 |

|

Black or African American |

82 |

|

White |

58 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

58 |

|

Male |

60 |

|

Education level (aged 25 to 64 years) |

|

|

Less than high school |

22 |

|

High school graduate |

17 |

|

At least some college |

8 |

|

Disability status |

|

|

Persons with disabilities |

DNC |

|

Persons without disabilities |

DNC |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

12-8. | (Developmental) Increase the proportion of adults who are aware of the early warning symptoms and signs of a stroke. |

Potential data source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

12-9. | Reduce the proportion of adults with high blood pressure. |

Target: 16 percent.

Baseline: 28 percent of adults aged 20 years and older had high blood pressure in 1988–94 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting method: Better than the best.

Data source: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults Aged 20 Years and Older, 1988–94 (unless noted) |

High Blood |

|

Percent |

|

|

TOTAL |

28 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

DSU |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

DSU |

|

Asian |

DNC |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

DNC |

|

Black or African American |

40 |

|

White |

27 |

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino |

DSU |

|

Mexican American |

29 |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

28 |

|

Black or African American |

40 |

|

White |

27 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

26 |

|

Male |

30 |

|

Family income level |

|

|

Poor |

32 |

|

Near poor |

30 |

|

Middle/high income |

27 |

|

Disability status |

|

|

Persons with disabilities |

32 (1991–94) |

|

Persons without disabilities |

27 (1991–94) |

|

Select populations |

|

|

Persons with diabetes |

DNA |

|

Persons without diabetes |

DNA |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

Increase the proportion of adults with high blood pressure whose blood pressure is under control. |

Target: 50 percent.

Baseline: 18 percent of adults aged 18 years and older with high blood pressure had it under control in 1988–94 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting method: Better than the best.

Data source: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults Aged 18 Years and Older With High Blood Pressure, 1988–94 (unless noted) |

Blood Pressure Controlled |

|

Percent |

|

|

TOTAL |

18 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

DSU |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

DSU |

|

Asian |

DNC |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

DNC |

|

Black or African American |

19 |

|

White |

18 |

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino |

DSU |

|

Mexican American |

13 |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

DNA |

|

Black or African American |

19 |

|

White |

18 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

28 |

|

Male |

13 |

|

Family income level |

|

|

Poor |

25 |

|

Near poor |

20 |

|

Middle/high income |

16 |

|

Disability status (aged 20 years and older) |

|

|

Persons with disabilities |

24 (1991–94) |

|

Persons without disabilities |

16 (1991–94) |

|

Select populations |

|

|

Persons with diabetes |

DNA |

|

Persons without diabetes |

DNA |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

12-11. | Increase the proportion of adults with high blood pressure who are taking action (for example, losing weight, increasing physical activity, or reducing sodium intake) to help control their blood pressure. |

Target: 95 percent.

Baseline: 82 percent of adults aged 18 years and older with high blood pressure were taking action to control it in 1998 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting method: Better than the best.

Data source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults Aged 18 Years and

Older With |

Taking

Action |

|

Percent |

|

|

TOTAL |

82 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

DSU |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

76 |

|

Asian |

75 |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

DSU |

|

Black or African American |

86 |

|

White |

80 |

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino |

74 |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

83 |

|

Black or African American |

87 |

|

White |

81 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

83 |

|

Male |

80 |

|

Family income level |

|

|

Poor |

80 |

|

Near poor |

79 |

|

Middle/high income |

81 |

|

Disability status |

|

|

Persons with activity limitations |

84 (1994) |

|

Persons without activity limitations |

76 (1994) |

|

Geographic variation |

|

|

Urban |

83 |

|

Rural |

80 |

|

Select populations |

|

|

Persons with diabetes |

DNA |

|

Persons without diabetes |

DNA |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

12-12. | Increase the proportion of adults who have had their blood pressure measured within the preceding 2 years and can state whether their blood pressure was normal or high. |

Target: 95 percent.

Baseline: 90 percent of adults aged 18 years and older had their blood pressure measured in the past 2 years and could state whether it was normal or high in 1998 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting method: Better than the best.

Data source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults Aged 18 Years and Older, 1998 (unless noted) |

Had

Blood Pressure |

|

Percent |

|

|

TOTAL |

90 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

89 |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

86 |

|

Asian |

86 |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

86 |

|

Black or African American |

92 |

|

White |

90 |

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino |

84 |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

91 |

|

Black or African American |

92 |

|

White |

91 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

92 |

|

Male |

87 |

|

Education level (aged 25 years and older) |

|

|

Less than high school |

84 |

|

High school graduate |

90 |

|

At least some college |

93 |

|

Disability status |

|

|

Persons with activity limitations |

90 (1994) |

|

Persons without activity limitations |

84 (1994) |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

Reduce the mean total blood cholesterol levels among adults. |

Target: 199 mg/dL (mean).

Baseline: 206 mg/dL was the mean total blood cholesterol level for adults aged 20 years and older in 1988–94 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting method: Better than the best.

Data source: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults Aged 20 Years and Older, 1988–94 (unless noted) |

Mean Cholesterol Level |

|

mg/dL |

|

|

TOTAL |

206 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

DSU |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

DSU |

|

Asian |

DNC |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

DNC |

|

Black or African American |

204 |

|

White |

206 |

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino |

DSU |

|

Mexican American |

205 |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

206 |

|

Black or African American |

204 |

|

White |

206 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

207 |

|

Male |

204 |

|

Family income level |

|

|

Poor |

205 |

|

Near poor |

204 |

|

Middle/high income |

206 |

|

Disability status |

|

|

Persons with disabilities |

208 (1991–94) |

|

Persons without disabilities |

204 (1991–94) |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

Reduce the proportion of adults with high total blood cholesterol levels. |

Target: 17 percent.

Baseline: 21 percent of adults aged 20 years and older had total blood cholesterol levels of 240 mg/dL or greater in 1988–94 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting method: Better than the best.

Data source: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults Aged 20 Years and Older, 1988–94 (unless noted) |

Total

Blood |

|

Percent |

|

|

TOTAL |

21 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

DSU |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

DSU |

|

Asian |

DNC |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

DNC |

|

Black or African American |

19 |

|

White |

21 |

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino |

DNC |

|

Mexican American |

18 |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

DNA |

|

Black or African American |

19 |

|

White |

21 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

22 |

|

Male |

19 |

|

Education level |

|

|

Less than high school |

22 |

|

High school graduate |

22 |

|

At least some college |

19 |

|

Disability status |

|

|

Persons with disabilities |

24 (1991–94) |

|

Persons without disabilities |

19 (1991–94) |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

12-15. | Increase the proportion of adults who have had their blood cholesterol checked within the preceding 5 years. |

Target: 80 percent.

Baseline: 67 percent of adults aged 18 years and older had their blood cholesterol checked within the preceding 5 years in 1998 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting method: Better than the best.

Data source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults Aged 18 Years and Older, 1998 (unless noted) |

Blood Cholesterol Checked in Past 5 Years |

|

Percent |

|

|

TOTAL |

67 |

|

Race and ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

58 |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander |

68 |

|

Asian |

69 |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

65 |

|

Black or African American |

67 |

|

White |

67 |

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino |

59 |

|

Not Hispanic or Latino |

68 |

|

Black or African American |

67 |

|

White |

70 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

70 |

|

Male |

64 |

|

Education level (aged 25 years and older) |

|

|

Less than high school |

58 |

|

High school graduate |

69 |

|

At least some college |

78 |

|

Disability status |

|

|

Persons with activity limitations |

72 (1993) |

|

Persons without activity limitations |

66 (1993) |

|

Geographic variation |

|

|

Urban |

68 |

|

Rural |

63 |

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

12-16. | (Developmental) Increase the proportion of persons with coronary heart disease who have their LDL-cholesterol level treated to a goal of less than or equal to 100 mg/dL. |

Potential data source: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), CDC, NCHS.

(A listing of acronyms and abbreviations used in this publication appears in Appendix H.)

Angina (angina pectoris): A pain or discomfort in the chest that occurs when some part of the heart does not receive enough blood. Angina is a common symptom of coronary heart disease. It often recurs in a regular or characteristic pattern. However, it may first appear as a very severe episode or as frequently recurring bouts. When an established stable pattern of angina changes sharply—for example, it may be provoked by far less exercise than in the past, or it may appear at rest—it is referred to as unstable angina.

Angioplasty: A nonsurgical procedure used to treat blockages in blood vessels, particularly the coronary arteries that feed the heart. Also known as percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). An inflatable balloon or other device on a thin tube (catheter), fed through blood vessels to the point of blockage, is used to open the artery.

Anticoagulants: Drugs that delay the clotting (coagulation) of blood. When a blood vessel is plugged up by a clot and an anticoagulant is given, it tends to prevent new clots from forming or the existing clot from enlarging. An anticoagulant does not dissolve an existing blood clot.

Arrhythmia: A change in the regular beat or rhythm of the heart. The heart may seem to skip a beat, or beat irregularly, or beat very fast or very slowly.

Atherosclerosis: A type of hardening of the arteries in which cholesterol and other substances in the blood are deposited in the walls of arteries, including the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart. In time,narrowing of the coronary arteries by atherosclerosis may reduce the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the heart.

Atrial fibrillation (AF): The most common sustained irregular heart rhythm encountered in clinical practice. AF occurs when the two small upper chambers of the heart (the atria) quiver instead of beating effectively, and blood cannot be pumped completely out of them when the heart beats, allowing the blood to pool and clot. If a piece of the blood clot in the atria becomes lodged in an artery in the brain, a stroke may result. AF is a risk factor for stroke and heart failure.

Blood pressure: The force of the blood pushing against the walls of arteries. Blood pressure is given as two numbers that measure systolic pressure (the first number, which measures the pressure while the heart is contracting) and diastolic pressure(the second number, which measures the pressure when the heart is resting between beats). Blood pressures of 140/90 mmHg or above are considered high, while blood pressures in the range of 130–139/85–89 are high normal. Less than 130/85 mmHg is normal.

Body mass index (BMI): Weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of height (in meters), or weight (in pounds) divided by the square of height (in inches) times 704.5. Because it is readily calculated, BMI is the measurement of choice as an indicator of healthy weight, overweight, and obesity.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD): Includes a variety of diseases of the heart and blood vessels, coronary heart disease (coronary artery disease, ischemic heart disease), stroke (brain attack), high blood pressure (hypertension), rheumatic heart disease, congestive heart failure, and peripheral artery disease.

Cerebrovascular disease: Affects the blood vessels supplying blood to the brain. Stroke occurs when a blood vessel bringing oxygen and nutrients to the brain bursts or is clogged by a blood clot. Because of this rupture or blockage, part of the brain does not get the flow of blood it needs, and nerve cells in the affected area die. Small stroke-like events, such as transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), which resolve in a day or less, are symptoms of cerebrovascular disease.

Cholesterol: A waxy substance that circulates in the bloodstream. When the level of cholesterol in the blood is too high, some of the cholesterol is deposited in the walls of the blood vessels. Over time, these deposits can build up until they narrow the blood vessels, causing atherosclerosis, which reduces the blood flow. The higher the blood cholesterol level, the greater is the risk of getting heart disease. Blood cholesterol levels of less than 200 mg/dL are considered desirable. Levels of 240 mg/dL or above are considered high and require further testing and possible intervention. Levels of 200–239 mg/dL are considered borderline. Lowering blood cholesterol reduces the risk of heart disease.

Congestive heart failure (or heart failure): A condition in which the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the needs of the body’s other organs. Heart failure can result from narrowed arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle and from other factors. As the flow of blood out of the heart slows, blood returning to the heart through the veins backs up, causing congestion in the tissues. Often swelling (edema) results, most commonly in the legs and ankles, but possibly in other parts of the body as well. Sometimes fluid collects in the lungs and interferes with breathing, causing shortness of breath, especially when a person is lying down.

Coronary heart disease (CHD): A condition in which the flow of blood to the heart muscle is reduced. Like any muscle, the heart needs a constant supply of oxygen and nutrients that are carried to it by the blood in the coronary arteries. When the coronary arteries become narrowed or clogged, they cannot supply enough blood to the heart. If not enough oxygen-carrying blood reaches the heart, the heart may respond with pain called angina. The pain usually is felt in the chest or sometimes in the left arm or shoulder. When the blood supply is cut off completely, the result is a heart attack. The part of the heart muscle that does not receive oxygen begins to die, and some of the heart muscle is permanently damaged.

Coronary stenting: A procedure that uses a wire mesh tube (a stent) to prop open an artery that recently has been cleared using angioplasty. The stent remains in the artery permanently, holding it open to improve blood flow to the heart muscle and relieve symptoms, such as chest pain.

HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol: The so-called good cholesterol. Cholesterol travels in the blood combined with protein in packages called lipoproteins. HDL is thought to carry cholesterol away from other parts of the body back to the liver for removal from the body. A low level of HDL increases the risk for CHD, whereas a high HDL level helps protect against CHD.

Heart attack (also called acute myocardial infarction): Occurs when a coronary artery becomes completely blocked, usually by a blood clot (thrombus), resulting in lack of blood flow to the heart muscle and therefore loss of needed oxygen. As a result, part of the heart muscle dies (infarcts). The blood clot usually forms over the site of a cholesterol-rich narrowing (or plaque) that has burst or ruptured.

Heart disease: The leading cause of death and a common cause of illness and disability in the United States. Coronary heart disease and ischemic heart disease are specific names for the principal form of heart disease, which is the result of atherosclerosis, or the buildup of cholesterol deposits in the coronary arteries that feed the heart.

High blood pressure: A systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or greater or a diastolic pressure of 90 mmHg or greater. With high blood pressure, the heart has to work harder, resulting in an increased risk of a heart attack, stroke, heart failure, kidney and eye problems, and peripheral vascular disease.

Ischemic heart disease: Includes heart attack and related heart problems caused by narrowing of the coronary arteries and therefore a decreased supply of blood and oxygen to the heart. Also called coronary artery disease and coronary heart disease.

LDL (low-density lipoprotein): The so-called bad cholesterol. LDL contains most of the cholesterol in the blood and carries it to the tissues and organs of the body, including the arteries. Cholesterol from LDL is the main source of damaging buildup and blockage in the arteries. The higher the level of LDL in the blood, the greater is the risk for CHD.

Lipid: Fat and fat-like substances such as cholesterol that are present in blood and body tissues.

Peripheral vascular disease: Refers to diseases of any blood vessels outside the heart and to diseases of the lymph vessels. It is often a narrowing of the blood vessels that carry blood to leg and arm muscles. Symptoms include leg pain (for example, in the calves) when walking and ulcers or sores on the legs and feet.

Stroke: A form of cerebrovascular disease that affects the arteries of the central nervous system. A stroke occurs when blood vessels bringing oxygen and nutrients to the brain burst or become clogged by a blood clot or some other particle. Because of this rupture or blockage, part of the brain does not get the flow of blood it needs. Deprived of oxygen, nerve cells in the affected area of the brain cannot function and die within minutes. When nerve cells cannot function, the part of the body controlled by these cells cannot function either.

[1] National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Morbidity and Mortality: 1998 Chartbook on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases. Bethesda, MD: Public Health Service (PHS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), NHLBI, October 1998.

[2] Sempos, C.T.; Cleeman, J.I.; Carroll, M.K.; et al. Prevalence of high blood cholesterol among U.S. adults: An update based on guidelines from the second report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel. Journal of the American Medical Association 269:3009-3014, 1993. PubMed; PMID 8501843

[3] Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. National Cholesterol Education Program: Second report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II). Circulation 89:1329-1445, 1994. PubMed; PMID 8124825

[4] The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Archives of Internal Medicine 157(21):2413-2446, 1997. PubMed; PMID 9385294

[5] Burt, V.L.; Culter, J.A.; Higgins, M.; et al. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult U.S. population. Hypertension 26:60-69, 1995. PubMed; PMID 7607734

[6] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Mortality from congestive heart failure—United States, 1980–1990. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 43(5):77-78, 1994. PubMed; PMID 8295629

[7] Gillum, R.F. Epidemiology of heart failure in the United States. American Heart Journal 126:1042-1047, 1993. PubMed; PMID 8213434

[8] Lenfant, C. Fixing the failing heart. Circulation 95:771-772, 1997. PubMed; PMID 9054724

[9] Croft, J.B.; Giles, W.H.; Pollard, R.A.; et al. National trends in the initial hospitalizations for heart failure. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45:270-275, 1997. PubMed; PMID 9063270

[10] American Heart Association (AHA). 2000 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. Dallas, TX: AHA, 2000.

[11] Huston, S.L.; Lengerich, E.J.; Conlisk, E.; et al. Trends in ischemic heart disease death rates for blacks and whites—United States, 1981–1995. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review 47:945-949, 1998. PubMed; PMID 9832470

[12] Gillum, R.F.; Muscolino, M.F.; and Madans, J.A. Fatal MI among black men and women. Annals of Internal Medicine 127:111-118, 1997.

[13] National Heart Attack Alert Program Coordination Committee. Working Group Report on Educational Strategies To Prevent Prehospital Delay in Patients at High Risk for Acute Myocardial Infarction. NIH Pub. No. 97-3787. Bethesda, MD: NIH, NHLBI, 1997.

[14] Burt, V.; Whelton, P.; and Roccella, E.J. Prevalence of hypertension in the U.S. adult population. Hypertension 25:305-313, 1995. PubMed; PMID 7875754

[15] Stone, N.J. Primary prevention of coronary disease. Clinical Cornerstone 1(1):31-49, 1998. PubMed; PMID 10682162

[16] Benson, R.T., and Sacco, R.L. Stroke prevention: Hypertension, diabetes, tobacco, and lipids. Neurologic Clinics 18(2):309-319, 2000. PubMed; PMID 10757828

[17] Paffenbarger, Jr., R.S.; Hyde, R.T.; Wing, A.; et al. The association of changes in physical activity levels and other lifestyle characteristics with mortality among men. New England Journal of Medicine 328:538-545, 1993. PubMed; PMID 8426621

[18] Blair, S.N.; Kampert, J.B.; Kohl, H.W.; et al. Influences of cardiopulmonary fitness and other precurors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. Journal of the American Medical Association 276:205-210, 1996. PubMed; PMID 9624649

[19] American Diabetes Association (ADA). Diabetes 1996: Vital Statistics. Alexandria, VA: ADA, 1996.

[20] He, J.; Whelton, P.K., Appel, L.J.; et al. Long-term effects of weight loss and dietary sodium reduction on incidence of hypertension. Hypertension 35(2):544-549, 2000. PubMed; PMID 10679495

[21] Leiter, L.A.; Abbott, D.; Campbell, N.R.; et al. Lifestyle modifications to prevent and control hypertension. 2. Recommendations on obesity and weight loss. Canadian Hypertension Society, Canadian Coalition for High Blood Pressure Prevention and Control, Laboratory Centre for Disease Control at Health Canada, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal 160(Suppl. 9):S7-12, 1999. PubMed; PMID 10333848

[22] Hooper, L.; Summerbell, C.D.; Higgins, J.P.; et al. Reduced or modified dietary fat for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database System Review 2:CD002137, 2000.

[23] Pate, R.R.; Pratt, M.; Blair, S.N.; et al. Physical activity and public health: A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association 273:402-407, 1995. PubMed; PMID 7823386

[24] Physical activity and cardiovascular health. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health. Journal of the American Medical Association 276(3):241-246, 1996. PubMed; PMID 8667571

[25] Dunn, A.L.; Marcus, B.H.; Kampert, J.B.; et al. Comparison of lifestyle and structured interventions to increase physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 281:327-334, 1999. PubMed; PMID 9929085

[26] Manson, J.A.; Hu, F.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; et al. A prospective study of walking as compared with vigorous exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease in women. New England Journal of Medicine 341:650-658, 1999. PubMed; PMID 10460816

[27] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: HHS, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), 1996.

[28] HHS. The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General. HHS Pub. No. CDC 90-8416. Atlanta, GA: HHS, PHS, CDC, NCCDPHP, Office on Smoking and Health, 1990.

[29] Freedman, D.S.; Dietz, W.H.; Srinivasan, S.R.; et al. The relation of overweight to cardiovascular risk factors among children and adolescents: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics 103:1175-1182, 1999. PubMed; PMID 10353925

[30] Winkleby, M.; Robinson, T.; Sundquist, J.; et al. Ethnic variations in cardiovascular disease risk factors among children and young adults: Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1998–1994. Journal of the American Medical Association 281(11):1006-1013, 1999. PubMed; PMID 10086435

[31] Leon, A.S.; Cornett, J.; Jacobs, Jr., D.R.; et al. Leisure time physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease and death: The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 258:2388-2395, 1987. PubMed; PMID 3669210

[32] O’Connor, G.T.; Hennekens, C.H.; Willett, W.H.; et al. Physical exercise and reduced risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction. American Journal of Epidemiology 142:1147-1156, 1995. PubMed; PMID 7485061

[33] Blair, S.N.; Kohl, III, H.W.; Barlow, C.E.; et al. Changes in physical fitness and all cause mortality: A prospective study of healthy and unhealthy men. Journal of the American Medical Association 273:1093-1098, 1995. PubMed; PMID 7707596

[34] Willett, W.H.; Dietz, W.H.; and Colditz, G.A. Primary care: Guidelines for healthy weight. New England Journal of Medicine 341:427-434, 1999. PubMed; PMID 10432328

[35] Roccella, E.J., and Horan, M.J. The National High Blood Pressure Education Program: Measuring progress and assessing its impact. Health Psychology (Suppl. 7):237-303, 1998. PubMed; PMID 3243223

[36] National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Health, United States, 1998. Hyattsville, MD: HHS, CDC, NCHS, 1998.

[37] Kannel, W.B.; Dawber, T.R.; and McGee, D.L. Perspectives on systolic hypertension, the Framingham Study. Circulation 61:1179-82, 1980. PubMed; PMID 7371130

[38] Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the SHEP. Journal of the American Medical Association 265:3255-3264, 1991. PubMed; PMID 2046107

[39] Cleeman, J.I., and Lenfant, C. The National Cholesterol Education Program: Progress and prospects. Journal of the American Medical Association 280:2099-2104, 1998. PubMed; PMID 9875878

[40] NHLBI. Cholesterol Awareness Surveys. Press conference. Bethesda, MD: NHLBI, December 4, 1995.

[41] Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: Evidence report. Journal of Obesity Research (Suppl. 2):51S-204S, 1998. PubMed; PMID 9813653

[42] HHS. Smoking Cessation. Clinical Practice Guidelines No. 18. HHS Pub. No. (AHCPR) 96-0692. Washington, DC: HHS, PHS, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1996.

[43] Benson, V., and Marano, M.A. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), 1995. Vital and Health Statistics 10(199):1-428, 1998.

[44] National Heart Attack Alert Program Coordinating Committee, 60 Minutes to Treatment Working Group. Emergency Department: Rapid identification and treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Annals of Emergency Medicine 23:311-329, 1994. PubMed; PMID 8304613

[45] Ryan, T.J.; Antman, E.M.; Brooks, N.H.; et al. 1999 update: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction). Journal of the American College of Cardiology 34:890-911, 1999. PubMed; PMID 10483976

[46] Boersma, E.; Maas, A.C.P.; Deckers, J.W.; et al. Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: Reappraisal of the golden hour. Lancet 348:771-775, 1996. PubMed; PMID 8813982

[47] Betts, J.H. Late assessment of thrombolytic efficacy with altiplase (rt-PA) 6-24 hours after onset of acute myocardial infarction. Australian New Zealand Journal of Medicine 23:745-748, 1993.

[48] Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndrome’s (GUSTO IIb) Angioplasty Substudy Investigators. A clinical trial comparing primary coronary angioplasty with tissue plasminogen activator for acute myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine 336:1621-1628, 1997. PubMed; PMID 9173270

[49] Bahr, R.D. Introduction: community message in acute myocardial ischemia. Clinician 14:1, 1996.

[50] National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. New England Journal of Medicine 333(24):1581-1587, 1995. PubMed; PMID 7477192

[51] ADA. Emergency Cardiovascular Care Programs. Chain of Survival. Links in the Chain. <http://www.proed.net/ecc/chain/links.htm>June 1999.

[52] National Heart Attack Alert Program Coordinating Committee, Access to Care Subcommittee. Access to timely and optimal care of patients with acute coronary syndromes—Community planning considerations: Report by the National Heart Attack Alert Program. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis 6:19-46, 1998. PubMed; PMID 10753312

[53] National Heart Attack Alert Program. Patient/Bystander Recognition and Action: Rapid Identification and Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction. NIH Pub. No. 93-3303 Bethesda, MD: NHLBI, NIH, 1993.

[54] Criqui, M.H.; Langer, R.D.; Fronek, A.; et al. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. New England Journal of Medicine 326(6):381-386, 1992. PubMed; PMID 1729621

[55] Salonen, J.T., and Salonen, R. Ultrasonographically assessed carotid morphology and the risk of coronary heart disease. Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis 11(5):1245-1249, 1991. PubMed; PMID 1911709

[56] Kannel, W.B., and Schatzkin, A. Sudden death: Lessons from subsets in population studies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 5(Suppl. 6):141-149B, 1985. PubMed; PMID 3889106

[57] Kuller, L.; Perper, J.; and Cooper, M. Demographic characteristics and trends in arteriosclerotic heart disease mortality: Sudden death and myocardial infarction. Circulation 51(Suppl. 1):III-1-III-15, 1975. PubMed; PMID 1182964

[58] Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomized trial of cholesterol lowering in 4,444 patients with coronary heart disease: The Scandinavian Simvastat in Survival Study (4S). Lancet 334:1383-1389, 1994. PubMed; PMID 7968073

[59] Sacks, F.M.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Moye, L.A.; et al., for the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. New England Journal of Medicine 335:1001-1009, 1996. PubMed; PMID 8801446

[60] Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. New England Journal of Medicine 339:1349-1357, 1998. PubMed; PMID 9841303