Alzheimer's Disease Genetics Fact Sheet

Scientists don't yet fully understand what causes Alzheimer's disease. However, the more they learn about this devastating disease, the more they realize that genes* play an important role in its development. Research conducted and funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) at the National Institutes of Health and others is advancing the field of Alzheimer's disease genetics.

*Terms in bold are defined at the end of this fact sheet.

The Genetics of Disease

Some diseases are caused by a genetic mutation, or permanent change in one or more specific genes. If a person inherits from a parent a genetic mutation that causes a certain disease, then he or she will usually get the disease. Sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, and early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease are examples of inherited genetic disorders.

In other diseases, a genetic variant may occur. This change in a gene can sometimes cause a disease directly. More often, it acts to increase or decrease a person's risk of developing a disease or condition. When a genetic variant increases disease risk but does not directly cause a disease, it is called a genetic risk factor.

Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics

Alzheimer's disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disease. It is characterized by the development of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, the loss of connections between nerve cells, or neurons, in the brain, and the death of these nerve cells. There are two types of Alzheimer's—early-onset and late-onset. Both types have a genetic component.

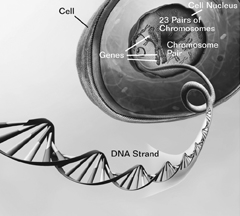

DNA, Chromosomes, and GenesThe nucleus of almost every human cell contains a “blueprint” that carries the instructions a cell needs to do its job. The blueprint is made up of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), which is present in long strands that would stretch to nearly 6 feet in length if attached end to end. The DNA is packed tightly together with proteins into compact structures called chromosomes. Normally, each cell has 46 chromosomes in 23 pairs, which are inherited equally from a father and a mother. The DNA in nearly all cells of an individual is identical. Each chromosome contains many thousands of segments, called genes. People inherit two copies of each gene from their parents, except for genes on the X and Y chromosomes, which, among other functions, determine a person's sex. The genes “instruct” the cell to make unique proteins that, in turn, dictate the types of cells made. Genes also direct almost every aspect of the cell's construction, operation, and repair. Even slight changes in a gene can produce a protein that functions abnormally, which may lead to disease. Other changes in genes may increase or decrease a person's risk of developing a particular disease. |

Early-Onset Alzheimer's Disease

Early-onset Alzheimer's disease occurs in people age 30 to 60. It is rare, representing less than 5 percent of all people who have Alzheimer's. Some cases of early-onset Alzheimer's have no known cause, but most cases are inherited, a type known as familial Alzheimer's disease (FAD).

Familial Alzheimer's disease is caused by any one of a number of different single-gene mutations on chromosomes 21, 14, and 1. Each of these mutations causes abnormal proteins to be formed. Mutations on chromosome 21 cause the formation of abnormal amyloid precursor protein (APP). A mutation on chromosome 14 causes abnormal presenilin 1 to be made, and a mutation on chromosome 1 leads to abnormal presenilin 2.

Scientists know that each of these mutations plays a role in the breakdown of APP, a protein whose precise function is not yet known. This breakdown is part of a process that generates harmful forms of amyloid plaques, a hallmark of the disease. A child whose mother or father carries a genetic mutation for FAD has a 50/50 chance of inheriting that mutation. If the mutation is in fact inherited, the child almost surely will develop FAD.

Critical research findings about early-onset Alzheimer's have helped identify key steps in the formation of brain abnormalities typical of Alzheimer's disease. They have also led to the development of imaging tests that show the accumulation of amyloid in the living brain. In addition, the study of Alzheimer's genetics has helped explain some of the variation in the age at which the disease develops.

NIA-supported scientists are continuing this research through the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN), an international partnership to study families with a genetic mutation that causes early-onset Alzheimer's disease. By observing the biological changes that occur in these families long before symptoms appear, scientists hope to gain insight into how and why the disease develops in both its early- and late-onset forms. In addition, scientists are attempting to develop tests that will enable diagnosis of Alzheimer's before clinical signs and symptoms appear, as it is likely that early treatment will be critical as therapies become available.

Late-Onset Alzheimer's Disease

Most cases of Alzheimer's are the late-onset form, which develops after age 60. The causes of late-onset Alzheimer's are not yet completely understood, but they likely include a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that influence a person's risk for developing the disease.

The single-gene mutations directly responsible for early-onset Alzheimer's disease do not seem to be involved in late-onset Alzheimer's. Researchers have not found a specific gene that causes the late-onset form of the disease. However, one genetic risk factor does appear to increase a person's risk of developing the disease. This increased risk is related to the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene found on chromosome 19. APOE contains the instructions for making a protein that helps carry cholesterol and other types of fat in the bloodstream. APOE comes in several different forms, or alleles. Three forms—APOE ε2, APOE ε3, and APOE ε4—occur most frequently.

- APOE ε2 is relatively rare and may provide some protection against the disease. If Alzheimer's disease occurs in a person with this allele, it develops later in life than it would in someone with the APOE ε4 gene.

- APOE ε3, the most common allele, is believed to play a neutral role in the disease—neither decreasing nor increasing risk.

- APOE ε4 is present in about 25 to 30 percent of the population and in about 40 percent of all people with late-onset Alzheimer's. People who develop Alzheimer's are more likely to have an APOE ε4 allele than people who do not develop the disease.

Dozens of studies have confirmed that the APOE ε4 allele increases the risk of developing Alzheimer's, but how that happens is not yet understood. These studies also help explain some of the variation in the age at which Alzheimer's disease develops, as people who inherit one or two APOE ε4 alleles tend to develop the disease at an earlier age than those who do not have any APOE ε4 alleles.

APOE ε4 is called a risk-factor gene because it increases a person's risk of developing the disease. However, inheriting an APOE ε4 allele does not mean that a person will definitely develop Alzheimer's. Some people with one or two APOE ε4 alleles never get the disease, and others who develop Alzheimer's do not have any APOE ε4 alleles.

Using a relatively new approach called genome-wide association study (GWAS), researchers have identified a number of genes in addition to APOE ε4 that may increase a person's risk for late-onset Alzheimer's, including BIN1, CLU, PICALM, and CR1. Finding genetic risk factors like these helps scientists better understand how Alzheimer's disease develops and identify possible treatments to study.

Genetic Testing

Although a blood test can identify which APOE alleles a person has, it cannot predict who will or will not develop Alzheimer's disease. It is unlikely that genetic testing will ever be able to predict the disease with 100 percent accuracy because too many other factors may influence its development and progression.

At present, APOE testing is used in research settings to identify study participants who may have an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's. This knowledge helps scientists look for early brain changes in participants and compare the effectiveness of treatments for people with different APOE profiles. Most researchers believe that APOE testing is useful for studying Alzheimer's disease risk in large groups of people but not for determining any one person's specific risk.

In doctors' offices and other clinical settings, genetic testing is used for people with a family history of early-onset Alzheimer's disease. However, it is not generally recommended for people at risk of late-onset Alzheimer's.

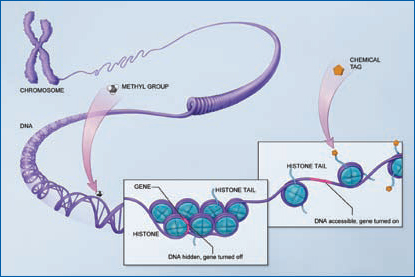

Epigenetics: Nature Meets NurtureScientists have long thought that genetic and environmental factors interact to influence a person's biological makeup, including the predisposition to different diseases. More recently, they have discovered the biological mechanisms for those interactions. The expression of genes (when particular genes are “switched” on or off) can be affected—positively and negatively—by environmental factors, such as exercise, diet, chemicals, or smoking, to which an individual may be exposed, even in the womb. Epigenetics is an emerging frontier of science focused on how and when particular genes are expressed. Diet and exposure to chemicals in the environment, among other factors, throughout all stages of life can alter a cell's DNA in ways that affect the activity of genes. That can make people more or less susceptible to developing a disease later in life. There is some emerging evidence that epigenetic mechanisms contribute to Alzheimer's disease. Epigenetic changes, whether protective, benign, or harmful, may help explain, for example, why one family member develops the disease and another does not. Research supported by the National Institutes of Health continues to explore this avenue.

The epigenome can “mark” DNA in two ways, both of which play a role in turning genes off or on. The first occurs when certain chemical tags called methyl groups attach to the backbone of a DNA molecule. The second occurs when a variety of chemical tags attach to the tails of histones, which are spool-like proteins that package DNA neatly into chromosomes. This action affects how tightly DNA is wound around the histones. |

Research Questions

Discovering all that we can about the role of Alzheimer's disease risk-factor genes is an important area of research. Understanding more about the genetic basis of the disease will help researchers:

- Answer a number of basic questions—What makes the disease process begin? Why do some people with memory and other thinking problems develop Alzheimer's while others do not?

- Determine how risk-factor genes may interact with other genes and lifestyle or environmental factors to affect Alzheimer's risk in any one person.

- Identify people who are at high risk for developing Alzheimer's so they can benefit from new interventions and treatments as soon as possible.

- Focus on new prevention and treatment approaches.

Major Alzheimer's Genetics Research Efforts UnderwayAs Alzheimer's disease genetics research has intensified, it has become clear that scientists need many genetic samples to make further progress. The National Institute on Aging supports several major genetics research programs.

The participation of volunteers is a critical part of Alzheimer's disease genetics research. The more genetic information that researchers can gather and analyze from a wide range of individuals and families, the more clues they will have for finding additional risk-factor genes. To learn more about the Alzheimer's Disease Genetics Study or to volunteer, contact NCRAD toll-free at 1-800-526-2839 or visit www.ncrad.org. |

For More Information

Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral (ADEAR) Center

P.O. Box 8250

Silver Spring, MD 20907-8250

1-800-438-4380 (toll-free)

www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers

The National Institute on Aging's ADEAR Center offers information and publications for families, caregivers, and professionals on diagnosis, treatment, patient care, caregiver needs, long-term care, education and training, and research related to Alzheimer's disease. Staff members answer telephone, email, and written requests and make referrals to local and national resources. The ADEAR website provides free, online publications in English and Spanish; email alerts; a clinical trials database; the Alzheimer's Disease Library database; and more.

Additional information about genetics in health and disease is available from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), part of the National Institutes of Health. Visit the NHGRI website at www.genome.gov.

The National Library of Medicine's National Center for Biotechnology Information also provides genetics information at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Alzheimer's Association

225 North Michigan Avenue

Floor 17

Chicago, IL 60601-7633

1-800-272-3900 (toll-free)

1-866-403-3073 (TTY/toll-free)

www.alz.org

Alzheimer's Foundation of America

322 Eighth Avenue, 7th floor

New York, NY 10001

1-866-232-8484 (toll-free)

www.alzfdn.org

Glossary

- Allele—A form of a gene. Each person receives two alleles of a gene, one from each biological parent. This combination is one factor among many that influence a variety of processes in the body. On chromosome 19, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene has three common forms or alleles: ε2, ε3, and ε4.

- Apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene—A gene on chromosome 19 involved in making a protein that helps carry cholesterol and other types of fat in the bloodstream. The APOE ε4 allele is considered a risk-factor gene for Alzheimer's disease and appears to influence the age at which the disease begins.

- Chromosome — A compact structure containing DNA and proteins present in nearly all cells of the body. Chromosomes carry genes, which direct the cell to make proteins and direct a cell's construction, operation, and repair. Normally, each cell has 46 chromosomes in 23 pairs. Each biological parent contributes one of each pair of chromosomes.

- DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid)—The hereditary material in humans and almost all other organisms. Almost all cells in a person's body have the same DNA. Most DNA is located in the cell nucleus.

- Gene—A basic unit of heredity. Genes direct cells to make proteins and guide almost every aspect of cells' construction, operation, and repair.

- Genetic mutation—A permanent change in a gene that can be passed on to children. The rare, early-onset familial form of Alzheimer's disease is associated with mutations in genes on chromosomes 1, 14, or 21.

- Genetic risk factor—A change in a gene that increases a person's risk of developing a disease.

- Genetic variant—A change in a gene that may increase or decrease a person's risk of developing a disease or condition.

- Genome-wide association study (GWAS)—A study approach that involves rapidly scanning complete sets of DNA, or genomes, of many individuals to find genetic variations associated with a particular disease.

- Protein—A substance that determines the physical and chemical characteristics of a cell and therefore of an organism. Proteins are essential to all cell functions and are created using genetic information.

Alzheimer’s Disease Education & Referral (ADEAR) Center

A Service of the National Institute on Aging

National Institutes of Health

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Publication Date: June 2011

Page Last Updated: April 9, 2012