Genomics in Action: Donald W. Hadley, M.S., C.G.C.

Getting Ahead of the Curve on Genetic Tests

By Jim Swyers, NHGRI Staff Writer

The sequencing of the human genome has accelerated the discovery of genes responsible

for a wide range of diseases, fueling an explosion in the development and marketing

of new genetic tests. At present, more than 800 genetic tests are available

for a variety of conditions - ranging from cancer to cystic fibrosis - and hundreds

more are in the developmental pipeline. To date, however, technological advances

have far outpaced our understanding of the most appropriate ways to use genetic

tests in real-life settings.

The sequencing of the human genome has accelerated the discovery of genes responsible

for a wide range of diseases, fueling an explosion in the development and marketing

of new genetic tests. At present, more than 800 genetic tests are available

for a variety of conditions - ranging from cancer to cystic fibrosis - and hundreds

more are in the developmental pipeline. To date, however, technological advances

have far outpaced our understanding of the most appropriate ways to use genetic

tests in real-life settings.

To help people better understand their rapidly expanding options in the genomic

era, a group at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), led by

genetic counselor and researcher Donald W. Hadley, M.S., C.G.C., is pursuing

"best practices" for genetic counseling and education. Mr. Hadley's

group also is exploring innovative approaches for educating the relatives of

patients who test positive for a genetic disease, which is an important step

because they also are at risk.

"Research is just beginning to identify the most effective and efficient

approaches to counsel patients and their families about genetic risk, the results

of genetic tests, and the clinical relevance of these technologies," said

Mr. Hadley, who is an associate investigator in the Social and Behavioral Research

Branch (SBRB) of the NHGRI Division of Intramural Research.

Mr. Hadley's particular area of focus is genetic testing for hereditary nonpolyposis

colorectal cancer (HNPCC), which is the most common inherited form of colon

cancer. About 145,000 new cases of colon cancer are diagnosed in the United

States each year. Although HNPCC is responsible for only about 5 percent of

those cases, it usually strikes at a much earlier age than non-inherited forms

of the disease. Regular screenings by colonoscopy and the removal of colon polyps

are critical for increasing the survival of people at risk for HNPCC.

Mr. Hadley's particular area of focus is genetic testing for hereditary nonpolyposis

colorectal cancer (HNPCC), which is the most common inherited form of colon

cancer. About 145,000 new cases of colon cancer are diagnosed in the United

States each year. Although HNPCC is responsible for only about 5 percent of

those cases, it usually strikes at a much earlier age than non-inherited forms

of the disease. Regular screenings by colonoscopy and the removal of colon polyps

are critical for increasing the survival of people at risk for HNPCC.

HNPCC can be caused by mutations in any one of at least a half dozen genes

whose encoded proteins are responsible for repairing mistakes that occur during

the process of DNA replication. Tests that detect mutations in these "DNA

mismatch repair genes" have emerged as important tools for identifying

individuals at risk for developing this disease.

People who have an HNPCC mutation face an 80 percent increased risk of developing

colon or rectal cancer by the time they are 70. They also have a significantly

greater risk for developing a number of other cancers, including those of the

uterus, stomach, ovaries, small intestine, biliary system and urinary tract.

This wide range of cancers makes it very challenging to counsel patients who

have a positive test for HNPCC.

"We cannot just discuss colon cancer risks with patients that test positive

for HNPCC mutations. We also have to tell them about their risk of a host of

other cancers and complications. In the case of a woman, we have the added responsibility

of educating and counseling her about an increased risk for endometrial (uterine)

and ovarian cancer," explained Mr. Hadley. "That is why research into

appropriate genetic counseling approaches for HNPCC and other types of genetic

testing is so critical."

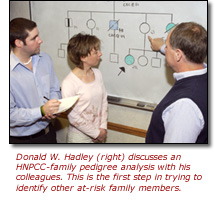

To investigate the effectiveness of genetic counseling and patient education

with HNPCC, Mr. Hadley has collaborated with researchers at the National Cancer

Institute and other institutions with access to large registries of cancer patients.

In one study, he and his collaborators offered genetic testing to 111 parents,

siblings and children of individuals with a diagnosis of HNPCC. The testing

was preceded by an educational session on HNPCC and followed by a genetic counseling

session.

To investigate the effectiveness of genetic counseling and patient education

with HNPCC, Mr. Hadley has collaborated with researchers at the National Cancer

Institute and other institutions with access to large registries of cancer patients.

In one study, he and his collaborators offered genetic testing to 111 parents,

siblings and children of individuals with a diagnosis of HNPCC. The testing

was preceded by an educational session on HNPCC and followed by a genetic counseling

session.

About half of the family members chose to undergo genetic testing and participate in the education and counseling sessions. The more first degree relatives a person had that experienced cancer, the more likely the person was to participate and pursue genetic testing. Other motivating factors for undergoing genetic testing were a desire to learn about their children's risks and an interest in knowing whether they needed to pursue cancer screening earlier and at more frequent intervals than the general population.

The researchers also found a significant amount of apprehension about genetic testing. The main concern was the potential for genetic discrimination by insurance companies, followed by concerns about the emotional aspects associated with the test outcome and the emotional effects it would have on other family members.

These findings illustrate how the prospect of facing multiple cancer risks can challenge individuals on personal, family and societal levels, making the genetic counseling process quite complicated. Research, therefore, cannot be focused only on those testing positive or negative for a mutation. "We are equally as interested in potentially at-risk individuals who choose not to undergo genetic testing as those who do. Information about the former could contribute important insight into concerns, attitudes and outcomes for those who are uninterested, afraid or untrusting of this technology," Mr. Hadley said.

Past research has not been successful in determining why some at-risk individuals choose to undergo genetic testing while others do not. According to Mr. Hadley, this is because genetic counseling researchers traditionally have relied on the family member with the initial diagnosis as the point of contact for the entire family. However, little is known about how effective these individuals are at communicating the necessary yet complicated information to their relatives. Likewise, there is little data on why some people decide not to share information about their genetic risk to other potentially at-risk relatives and what factors influence such decisions. "We believe it is extremely important to understand how families function, communicate, and act upon genetic information," said Mr. Hadley.

Equally important is understanding what people do once they know their genetic risk. In a study designed to provide some insights into whether genetic information affects health screening practices, Mr. Hadley and colleagues recently analyzed the use of colon cancer screening services by those with and without HNPCC mutations within families known to carry a HNPCC mutation. In a paper published in the January 1, 2004, issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology, the NHGRI group was encouraged to find that the use of colon cancer screening services decreased significantly and appropriately among those who tested negative for their family's HNPCC mutation, while it increased among those testing positive for the family mutation. Further research efforts are necessary to assess how women within these families fair in pursuing and obtaining screening for endometrial and ovarian cancers in addition to colon cancer.

Although the NHGRI group is making significant strides in closing the knowledge gap between genetic testing technology and genetic counseling, Mr. Hadley cautions that recent developments are threatening to widen that gap again. One particular challenge is a new type of assay that tests for hundreds of gene mutations at one time. Currently, genetic counselors spend an hour or more with each patient and their family discussing the implications of a mutation in a single gene. Counseling to discuss the results of a multi-gene test is likely to require even more intensive interactions.

"We are only beginning to scratch the surface of how to handle these more complicated situations," said Mr. Hadley. "Our ultimate goal is to be able to develop genetic counseling interventions for a variety of contexts that can then be used in a variety of clinical environments. To do that, however, we really need to get ahead of the curve, and soon."

Last Reviewed: March 13, 2012