Genomics in Action: Julie Segre, Ph.D.

Unlocking The Skin's Many Secrets

The National Human Genome Research Institute's (NHGRI) Julie Segre, Ph.D., is fascinated by how the body responds to the world around it, so she focuses on the body's largest organ: the skin.

The National Human Genome Research Institute's (NHGRI) Julie Segre, Ph.D., is fascinated by how the body responds to the world around it, so she focuses on the body's largest organ: the skin.

"The skin is a major organ system that has to interact with and adapt to the environment," said Dr. Segre. "It's the interface between our complex physiology and an often hostile environment that dries us out and exposes us to chemicals and infectious agents. You don't want kitchen cleanser in your bloodstream and your skin is the way you keep it out."

Although Dr. Segre's research centers on just one organ, what she has discovered gives us more information on every tissue that has contact with the outside world, including the surface of the eye, the intestinal tract, and the mucus membranes in the nose and lungs. Her work may also help create treatments for conditions as diverse as psoriasis, asthma and dehydration in premature babies.

Psoriasis and eczema are the principal disorders that Dr. Segre studies. Both show up first on the skin, but can affect several other areas of the body.

"These disorders are complex, multi-system problems," explained Dr. Segre, who is an investigator in the Genetics and Molecular Biology Branch of NHGRI's Division of Intramural Research. "If we can understand what happens with the skin, we may get clues about their underlying causes and how they create difficulties for us."

"While skin disorders primarily affect the quality of life, they can lead to serious problems if left untreated. Kids with eczema often develop asthma. Is it because the allergens that get in through breaks in the skin travel to the lungs or because one inflammatory process sets off another? We don't know yet, but we hope that if we learn how to manage eczema the patient won't develop asthma down the line. If they already have asthma, we hope that treating the skin problem will cause the asthma to improve."

Eczema starts between six months and one year of age with red, itchy patches that are sometimes mistaken for dry skin. The disorder is chronic, and the skin patches will come and go throughout life. Psoriasis usually develops between the ages of 20 and 30. Silvery patches form at places where the skin bends and breaks, such as knees and elbows. Psoriasis is also a chronic, relapsing condition and involves a lifetime of treatment. In the United States, 20 to 30 percent of the population has developed eczema, and 2 to 3 percent suffer from psoriasis.

Current medical wisdom says that both problems are caused by an overactive immune system that creates an allergic reaction in the skin, but Dr. Segre and her colleagues think that psoriasis and eczema can start with, rather than cause, skin breaks.

Once the skin barrier is broken, usually by a cut or scrape, allergens and infectious agents enter and start an inflammatory process. Most people heal the skin break quickly, and their immune system soon quiets down. However, the skin cells of people who have a genetic tendency towards psoriasis and eczema overreact to the challenge and get stuck in a cycle where the skin cells and the immune system stimulate each other in a continuous loop.

Once the skin barrier is broken, usually by a cut or scrape, allergens and infectious agents enter and start an inflammatory process. Most people heal the skin break quickly, and their immune system soon quiets down. However, the skin cells of people who have a genetic tendency towards psoriasis and eczema overreact to the challenge and get stuck in a cycle where the skin cells and the immune system stimulate each other in a continuous loop.

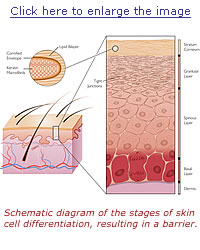

Schematic diagram of the stages of epidermal differentiation, resulting in a permeability barrier. Epidermal keratinocytes undergo a linear program of differentiation from mitotically active basal cells to transcriptionally active spinous cells to enucleated granular cells, resulting finally in differentiated squames in the stratum corneum. As shown in the inset, squames, which provide the primary barrier, are composed of keratin macrofibrils and cross-linked cornified envelopes encased in lipid bilayers. Tight junctions, located in the granular layer, also play an essential role in retaining the water content of the body. |

Role of barrier acquisition in the epidermal response to wound healing. Under normal conditions the epidermis serves as a barrier to retain water within the body and prevent the entry of infectious agents (e.g., microbes) or chemical agents. Dendritic Langerhans cells, resident in the epidermis, recognize, process, and present antigens to T lymphocytes. In response to trauma to the epidermis, depicted as a full-thickness epidermal wound, keratinocytes increase their proliferation rate and cytokine release. Keratinocytes proliferate and migrate to re-epithelialize the wounded area. T lymphocytes are recruited into the damaged skin. As part of the normal process, keratinocytes initiate the process of terminal differentiation to restore the epidermal barrier. However, if the process of terminal differentiation or barrier recovery is impaired, the skin can enter an inflammatory state. |

Although calming the immune system has been the major focus of most therapies for these disorders, Dr. Segre's laboratory made the practical discovery that healing the skin break is just as important as immune modulation for a good outcome. The group hopes that re-establishing the skin barrier, perhaps with a protective lotion or lipid bandage, will break the inflammatory loop and allow the immune system to stop reacting. That might mean that people with psoriasis and eczema would need lower doses of drugs and less treatment.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation (Connexin 26 regulates epidermal barrier and wound remodeling and promotes psoriasiform response), Segre and her colleagues recently found an important key to determining who will develop psoriasis and eczema by studying a protein called connexin 26 (Cx26). Cx26 forms communication channels that allow cells around a wound edge to tell each other to make more cells to close the wound; that tell cells in the underlying, undamaged skin layers that an emergency situation exists and ask them to make more cells; and that alert and attract immune cells to the damaged area to fight off pathogens while the wound heals. The skin produces large amounts of Cx26 when it is developing before birth, and also increases Cx26 production when tissues are damaged so they can regenerate.

Problems arise when the body does not turn off Cx26 production after a wound has healed. This puts the affected epithelial cells into an overdrive state called hyperproliferation, which stimulates the immune system. Dr. Segre hopes that finding ways to help the skin barrier heal quickly and efficiently in people with a genetic tendency to overproduce Cx26 will encourage Cx26 production to shut down in a timely manner and make it possible to minimize or eliminate psoriatic flares.

Premature babies are another group Dr. Segre and her colleagues hope they can help. They are studying how skin develops in the womb and establishes its marvelous protective barrier, and hope their new understanding will teach them how to speed up that process in premature infants, who are born before their skin is ready to keep bacteria out or body fluids in.

Premature babies are another group Dr. Segre and her colleagues hope they can help. They are studying how skin develops in the womb and establishes its marvelous protective barrier, and hope their new understanding will teach them how to speed up that process in premature infants, who are born before their skin is ready to keep bacteria out or body fluids in.

"Premature infants lose fluid at an alarming rate," said Dr. Segre. "If they are born before 34 weeks, so much fluid leaks out through their immature skin that they need to take in three times the amount of liquid of a baby born after 34 weeks just to keep their red blood cells, oxygen, electrolytes and nutrients circulating. We want to change that."

Learning how the skin develops will also help researchers create a synthetic barrier for thermal and chemical burn patients, whose damaged skin must be covered until new skin can regenerate. Dr. Segre said that people with severe burns have the same problems as premature infants, including difficulty maintaining body temperature, fluid loss and infection. Creating a synthetic barrier that can be put in place immediately may be crucial to surviving these acute injuries.

"Petroleum jelly just doesn't mimic skin," Dr. Segre said. "When we understand how skin truly works, we hope people will be able to design a synthetic barrier that can perform all the functions of the real one until the skin can heal itself."

Intriguingly, the past, not the present, may hold the key to much of Dr. Segre's research.

"You can't look at the world today and understand why our bodies respond the way they do," Dr. Segre remarked, "because our bodies are still programmed for earlier conditions. Antibiotics were only discovered in 1928, so strong, even drastic responses to breaks in our skin are still encoded in our genome to correct what would have been a life-threatening situation in the past."

Dr. Segre said that the rate of eczema in children is increasing, and may be due to the fact that our skin is programmed to coexist with dirt and farm animals, not clean suburban lawns.

"This is called the hygiene hypothesis," she explained. "It's not a fully developed story, but a number of disorders, including eczema, are becoming more common as people move into increasingly urban environments. It takes thousands, maybe millions of years to change our genome from an evolutionary standpoint. Society is evolving faster than our genome can respond."

Last Reviewed: March 13, 2012