Genomics in Action: Colleen McBride, Ph.D.

Social Science Meets the Genome

They don't peer through microscopes, clone genes or analyze readouts from robotic DNA sequencers. Yet, Colleen McBride, Ph.D., and colleagues at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) are conducting groundbreaking research in the field of genomics.

They don't peer through microscopes, clone genes or analyze readouts from robotic DNA sequencers. Yet, Colleen McBride, Ph.D., and colleagues at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) are conducting groundbreaking research in the field of genomics.

Their tools? Focus groups, models created to understand why people behave as they do, and statistical formulas. Their aim? Exploring how individuals, as well as society as a whole, respond to the discoveries of the genomic era.

The research portfolio overseen by Dr. McBride, who is a Senior Investigator and Chief of the Social and Behavioral Research Branch (SBRB) in NHGRI's Division of Intramural Research (DIR), is firmly seated in two very different worlds of scientific inquiry: molecular genetics and social science. Fittingly, she is convinced that the intersection of these two spheres holds the answers to many urgent questions facing genomics today. Do healthy people want information about their genetic risk for disease? Will people change their behaviors if genetic tests show they are at risk for disease? How will society treat people found to be at genetic risk for disease?

The SBRB fills a unique niche at NHGRI, most famous for the Human Genome Project. Health promotion, disease prevention and healthcare improvements achieved by social and behavioral scientists in virtually all other areas of medical research have great application to research about genetic inheritance and health outcomes.

Along with the requisite resume of social and behavioral science experience, Dr. McBride arrived at the NHGRI in 2002 with credentials for getting a new research program up and running. She has an impressive aptitude for dealing with uncertainty, a strong vision for new opportunities and an inclination for establishing where a new field of social science research might be headed. SBRB was launched under her stewardship in 2003.

"They told me when I got here that I could do whatever I wanted," Dr. McBride said. "That sounds like heaven. But, in reality, it was terrifying. I was new to genetics, and its application to the diseases that I wanted to study was - and still is - an absolutely wide-open landscape."

Dr. McBride previously had heard NHGRI Director Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D., speak about the future of medicine and genetics, and the important role that social and behavioral scientists will play in making this vision a reality. Since Dr. Collins had predicted that one of the great outgrowths of genetics would be personalized medicine tailored to an individual's own genome, she wanted to explore the promises and challenges involved with that idea.

What she discovered was that the majority of the social science research around genetics was related to the ethical, legal and social implications of genetic discovery. Protecting the public from potential abuses of genetic technologies - how these might violate privacy, compromise insurance and employment, and otherwise raise public anxiety - were the hot areas of study.

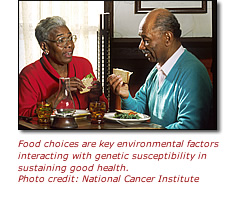

In addition, all the disorders associated with genetic tests were caused by defects in single "high-penetrance" genes that produce serious illnesses no matter what the individual does. These include cystic fibrosis, Huntington's disease and some familial cancer syndromes. Far fewer studies focused on "low-penetrance" genes that work in concert with behavioral and environmental factors to cause such conditions as diabetes, asthma and high blood pressure. No genetic tests for these more common conditions have yet been shown to be clinically useful.

Dr. McBride decided that her mission at NHGRI would be to figure out how to give people information on their genetic susceptibility to common health conditions. The goal was to encourage people to adopt healthy habits, such as eating better, getting more exercise and quitting smoking. She also thought that this new research branch should serve as a model for other programs. In line with NHGRI's traditional leadership role in genetics and genomics, she wanted SBRB to be a leader in creating tools that other social and behavioral scientists could use to advance social science research related to genetics.

Dr. McBride decided that her mission at NHGRI would be to figure out how to give people information on their genetic susceptibility to common health conditions. The goal was to encourage people to adopt healthy habits, such as eating better, getting more exercise and quitting smoking. She also thought that this new research branch should serve as a model for other programs. In line with NHGRI's traditional leadership role in genetics and genomics, she wanted SBRB to be a leader in creating tools that other social and behavioral scientists could use to advance social science research related to genetics.

"Basically, I had to take a deep breath, plug my nose and jump into my first task, which was to begin to assemble a team of full-time researchers," said Dr. McBride, adding "I was fortunate to have local colleagues to give me good advice and help conceptualize a framework for our research mission. And I got a great deal of support from the other leaders at NHGRI who wanted our branch to succeed. But I also felt a lot of pressure and that all eyes were upon me."

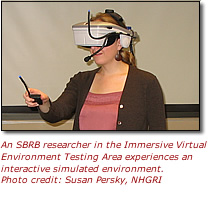

In spite of that pressure, Dr. McBride has met all her original goals. In three years, the branch has grown to a group of almost 50. She has started the Multiplex Initiative, a large, multi-disciplinary research collaboration to examine the effects of genetic susceptibility testing for eight common health conditions: type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, lung cancer, colorectal cancer and malignant melanoma. She also has created a Virtual Environment Lab that uses simulated social scenarios to help address research questions that are important to ask before introducing new genetic technologies.

The Multiplex Initiative was formulated by Dr. McBride and Larry Brody, Ph.D., a Senior Investigator in NHGRI's Genome Technology Branch, to explore outcomes of offering genetic susceptibility testing for common health conditions to the general public. Dr. Brody is a geneticist, and Dr. McBride says that the fact that he thinks very differently than she does is a tremendous advantage to the project. She also has worked with Andy Baxevanis, Ph.D., NHGRI's Deputy Scientific Director and Director of DIR's Computational Genomics Program, on the informatics aspects of this large, multi-center project, bringing yet another critical point-of-view to the table.

Participants in the Multiplex Initiative will come from a large primary health care system in the Midwest. The researchers hope to recruit 1,000 of these individuals to undergo genetic testing. "A basic question that we know surprisingly little about," said Dr. McBride, "is whether people actually are interested in having genetic testing to find out more about their level of genetic risk for health conditions such as heart disease, Type II diabetes, osteoporosis and various cancers."

The planning for the Multiplex Initiative has been immense. The genes included on the multiplex genetic test had to be selected carefully, so Drs. McBride and Brody worked for a year with a team of 30 scientific advisors to arrive at an accepted list of validated genetic tests. Half of these advisors were from outside NIH, and the group included epidemiologists, genetic counselors, oncologists, health psychologists, bioethicists, physicians and public health researchers.

NHGRI's Bioinformatics and Scientific Programming Core, under Dr. Baxevanis's leadership, created a Web-based program to help participants decide whether or not they wanted to be tested. This program will also play a key role in the collection of behavioral data, coordinating the flow of data between the individual research and testing centers.

These online tools are groundbreaking. The pros and cons of genetic susceptibility testing will be presented to research participants via an interactive interface that also will track what information they seek out, in what order they seek it, and how long they spend at each area of the site. Dr. McBride hopes the data will help her branch find the best way to offer genetic testing and what resources people need to make good use of it.

"The Multiplex Initiative online tools will give us objective measures of our outcomes," Dr. McBride explained. "Rather than people telling us what they did, which is influenced by what they think we want to hear, we can see for ourselves what actually happened. This increases the rigor of the science."

Recruitment for the Multiplex Initiative began Feb. 1 and Dr. McBride hopes to reach the project's enrollment goals by February 2008. "This is a quick turn-around project," said Dr. McBride. "We intentionally planned this study as a modest first step to jump start this line of research. So we hope to have a story to tell early next year - at least part of the story about how patients might respond to multiplex genetic testing."

Innovative research tools are being generated elsewhere at SBRB too. A case in point: the Virtual Environment Laboratory, which grew out of the branch's frustration with the fact that so little of the genetic technology forecast for the future is currently available. Because of this, the field of genetic testing research has had to rely on hypothetical scenarios about future technologies. "Obviously, this has a lot of limitations and relies heavily on our ability to vividly describe these hypothetical scenarios and our research subjects' abilities to imagine the scenarios we describe," said Dr. McBride.

Innovative research tools are being generated elsewhere at SBRB too. A case in point: the Virtual Environment Laboratory, which grew out of the branch's frustration with the fact that so little of the genetic technology forecast for the future is currently available. Because of this, the field of genetic testing research has had to rely on hypothetical scenarios about future technologies. "Obviously, this has a lot of limitations and relies heavily on our ability to vividly describe these hypothetical scenarios and our research subjects' abilities to imagine the scenarios we describe," said Dr. McBride.

By using computer technology to construct virtual worlds, Dr. McBride and colleagues can construct vivid and realistic scenarios that involve genetic technology that is not currently available. One such study seeks to understand how doctors interact with obese patients if they believe that the obesity has a genetic contribution. In the research, medical students will don elaborate headsets that enable them to become completely immersed in what feels to them like a true clinical scenario. The researchers can control every aspect of the virtual patient, down to facial expressions. This will allow the researchers to observe how the medical students act in response to genetic information, while factoring out distractions and situational variations that may influence their behavior.

"If we are going to move towards personalized medicine, these are important interactions to understand," explained Dr. McBride. "With common health conditions, the explanation will never be completely genetic. Since behavior and environment will always play an important role, we want to be able to help physicians present the data in a way that inspires people to take charge of their health."

Another priority is to determine the best way to present a new medical technology to the public. Dr. McBride said, "We already know a lot about why technologies take off and where they get stuck. We want to apply this information to clinical applications of genomic information, so that genetic testing technologies that have potential clinical value can be moved into the public domain." She added that one particular concern is that genetic and genomic technologies be distributed in ways that benefit all sectors of society.

According to Dr. McBride, many medical technologies and procedures have been developed with little forethought about how they would be received by target populations. For example, she notes that colonoscopies have not been well accepted by the public, even though the procedures are known to be effective in saving lives by detecting colon cancer early. The development of an effective test, therefore, is only part of the challenge. Dr. McBride wants to see behavioral and social outcomes considered from the start in shaping clinical applications of genomics for common health conditions.

Buoyed by the progress already made by her branch, Dr. McBride looks forward to opportunities to more closely align its research portfolio with the health questions of greatest concern to the general public. "What we've accomplished so far greatly exceeds my expectations, and we are incredibly well-positioned to do even more exciting research in the future."

Last Reviewed: March 13, 2012