Genomics in Action: Donna Krasnewich, M.D., Ph.D.

Refining the Genomics of Rare Sugar Metabolism Disorders

The way sugar behaves in the body is not always sweet. No one knows this better than the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) Deputy Clinical Director Donna Krasnewich, M.D., Ph.D. She is one of the world's foremost experts in the study and treatment of a group of rare genetic diseases collectively dubbed congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG).

The way sugar behaves in the body is not always sweet. No one knows this better than the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) Deputy Clinical Director Donna Krasnewich, M.D., Ph.D. She is one of the world's foremost experts in the study and treatment of a group of rare genetic diseases collectively dubbed congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG).

Dr. Krasnewich, who came to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1989, also is an associate investigator in the Division of Intramural Research's Medical Genetics Branch and head of the Medical Genetics Clinic. Trained as a pediatrician, with a specialty in clinical biochemical genetics, her research focuses on metabolic disorders.

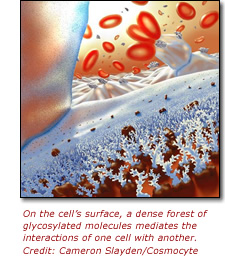

CDG are caused by genetic mutations that disrupt particular aspects of sugar metabolism. Sugar is well known for its role as an essential nutrient, but it also has important structural functions. Simple sugars are joined together to form complex branched sugars, or oligosaccharides, which are linked to the amino acid asparagine (whose single-letter amino acid code is N). These oligosaccharides are attached to proteins inside and on the surface of the cell and play a vital role in the growth and functioning of many tissues in the body.

Hundreds of different enzymes are required to construct these elaborate tree-like structures. A genetic mutation in any one of these can cause an enzyme to malfunction and prevent the cell from manufacturing the correct sugar chain. This can cause many clinical problems in children, with the range of symptoms and the severity of the disease depending on which enzyme is damaged. This makes CDG tricky to diagnose.

The underlying metabolic causes in CDG have been clear for many years. "If you can't make N-linked oligosaccharides then you have CDG," said Dr. Krasnewich. A lab test called transferrin isoform analysis can determine whether an individual has CDG, but does not reveal which enzyme in the glycosylation pathway is damaged. To date, 16 types of CDG have been identified. Only one of these disorders - CDG Type 1b - can be treated.

The underlying metabolic causes in CDG have been clear for many years. "If you can't make N-linked oligosaccharides then you have CDG," said Dr. Krasnewich. A lab test called transferrin isoform analysis can determine whether an individual has CDG, but does not reveal which enzyme in the glycosylation pathway is damaged. To date, 16 types of CDG have been identified. Only one of these disorders - CDG Type 1b - can be treated.

The spectrum of symptoms ranges from children with severe developmental issues, liver disease, neurological dysfunction, and eye and endocrine problems, to children who only have diarrhea and "failure to thrive" but are otherwise cognitively normal. "So the spectrum is enormous," said Dr. Krasnewich, "If you asked: 'What are the signs that a child has CDG?' The answer is: just about anything."

To illustrate her point, she grabbed a picture showing a group of children with CDG. "This boy is in a wheelchair; this one is walking around; this one is mildly cognitively impaired. In this group photo the children range from very growth impaired to average size kids," she explained.

Then, pointing to a picture of adults with CDG Type 1a, she added, "This man has an IQ of about 70. They all read at about a second or third grade level ... they are incredibly happy all the time, which just happens to be a constituency of their personalities. This young woman is pretty spirited and went to her senior prom ... these two people have neurological problems similar to being severely drunk because they have cerebellar issues." The cerebellum hones movement. When it doesn't function correctly an individual can generate movements but can't fine-tune them - making it difficult for children and adults with CDG to walk.

CDG cases are extremely rare, with only 100 to 150 in the United States and about 400 to 500 worldwide. Over the past 10 years of studying this disorder while at NHGRI, Dr. Krasnewich has met and examined many of the children with CDG in the United States, making her an invaluable hub of knowledge for families around the world.

"Genetics, in general, is a very holistic practice," said Dr. Krasnewich. Typically the children will spend up to four days with the NHGRI clinical researcher and her team. "We spend a lot of time addressing whatever is going on with the child. The families basically use me as their medical coordinator so that they can make judgments about management."

Dr. Krasnewich doesn't just work with the families; she often schools the family physicians and pediatricians who must learn how to care for a child with a form of CDG. About 10 to 12 times a month she gets a call from a physician who is caring for an affected child and needs to talk through things.

In many cases, Dr. Krasnewich is the key to connecting families and seemingly unrelated cases to enable everyone to share information about the disease. "How else can you do this unless you have a central person who is interested in the disorder? When you have a rare disease, you need someone to make it their baby and take it under their wing - that person has a collective knowledge that allows them to synergize with other people."

For Dr. Krasnewich, her goal is to understand the full range of disease symptoms and develop management strategies for patients along the entire CDG spectrum. "Some of these kids have a failure to thrive, so what's the best way to manage their feeding problems? That's something I'm specifically interested in right now."

About 25 percent of children with CDG Type 1a, which is the most common form of the disease, die in infancy. Why do they die? What is a predictor of a child who will never be hospitalized versus one who will? Is there some clinical marker that can identify children at particular risk? These are all issues that Dr. Krasnewich is trying to address through her research.

These days, Dr. Krasnewich doesn't need to see every case of CDG because many patients can receive good medical care from their physicians. She wants to focus on the more unusual cases. Understanding the clinical issues and therapeutic responses of children and adults with rare diseases not only helps an often neglected small group of patients, but frequently gives insight into common medical problems in larger populations.

"Here at the NIH, we only see extraordinary things - it's a wonderful place to practice medicine," said Dr. Krasnewich. "I have the luxury of time to spend with families. So if I have a child with CDG, I'll spend four or five hours with them at the beginning of the visit figuring out what's going on, priorities, sequence of events and their questions. That's very difficult to do in any other place."

Ultimately, Dr. Krasnewich hopes that her understanding of disease symptoms will converge with the identification of the genes causing the various forms of CDG. This would further illuminate the roles that oligosaccharides play in the body, and perhaps reveal therapeutic options for this group of diseases.

Last Reviewed: March 13, 2012