Genomics in Action: Ellen Sidransky, M.D.

Gaucher Disease: Opening a Window Into More Common Disorders

Ellen Sidransky, M.D., senior investigator in the National Human Genome Research Institute's Medical Genetics Branch, has been studying a genetic disorder known as Gaucher disease for 18 years, yet it still intrigues her.

Ellen Sidransky, M.D., senior investigator in the National Human Genome Research Institute's Medical Genetics Branch, has been studying a genetic disorder known as Gaucher disease for 18 years, yet it still intrigues her.

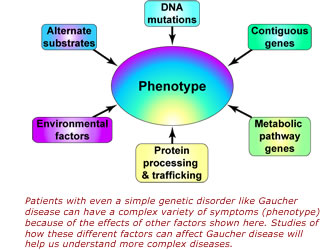

Because Gaucher disease produces a wide range of symptoms, almost every patient's problems are unique in some way. Complicating the picture further is the fact that patients with similar symptoms can have very different genetic mutations and, conversely, that patients with the same genetic mutation can experience very different symptoms.

So, Dr. Sidransky must be prepared for anything and everything when she sees someone with Gaucher disease. It's an endless puzzle that she finds endlessly fascinating.

"There are people who have had Gaucher disease all their lives and never know it until it is diagnosed coincidentally in their 70s or 80s," Dr. Sidransky said. "Some infants with the disease die soon after birth, and there are children whose spleen and liver are so enlarged that they look like teddy bears." Symptoms range from brittle bones and yellowish-brown skin to seizures and dementia.

Like cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia, Gaucher (pronounced go-SHAY) disease is caused by mutations in a single gene, called GBA. Gaucher disease is a recessive genetic disorder, meaning that a person must inherit a mutated copy of the GBA gene from both parents in order to become ill.

Dr. Sidransky often wonders how just one altered gene can produce so many different problems. "A seemingly simple disease like Gaucher disease is proving more complex than I ever anticipated," she remarked. "When we finally find out why, we will understand aspects of genetics that are now no more than guesswork. Gaucher disease will give us a window into more complicated genetic problems and a whole range of more common genetic disorders."

GBA is considered a "housekeeping" gene that handles basic cell maintenance. It helps produce the enzyme glucocerebrosidase, which breaks down a fat, called glucocerebroside, that is part of all cell membranes. When cells die, the body has no further use for glucocerebroside and it is tagged as waste to be picked up by scavenger white blood cells, called macrophages.

Macrophages (Greek for "big eaters") develop from a type of white blood cell, called a monocyte, that is produced in the spleen, liver and bone marrow. Their job is to engulf and break down cellular debris and pathogens, such as bacteria and viruses. They do this by sending the unwanted items into tiny organelles in their cytoplasm called lysosomes, where they are destroyed.

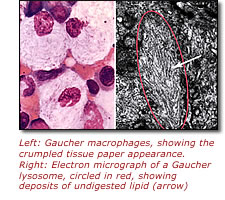

In people with Gaucher disease, macrophages produce defective or insufficient amounts of glucocerebrosidase, which means they cannot digest glucocerebroside. Instead, the fatty substance builds up inside the lysosomes, which get larger and larger until the macrophage looks like it is filled with crumpled tissue paper with its nucleus pushed to one side.

In people with Gaucher disease, macrophages produce defective or insufficient amounts of glucocerebrosidase, which means they cannot digest glucocerebroside. Instead, the fatty substance builds up inside the lysosomes, which get larger and larger until the macrophage looks like it is filled with crumpled tissue paper with its nucleus pushed to one side.

This build-up of glucocerebroside causes problems in the spleen, liver and bone marrow. Without treatment, the liver can expand to two or three times its normal size, and the size of the spleen can increase up to 20 times.

"We tell kids with Gaucher disease that having a lysosomal enzyme deficiency is like having a garbage strike in their cells," Dr. Sidransky said. "Unwanted 'stuff' just keeps accumulating until their yard fills up and becomes unpleasant."

Before the gene responsible for Gaucher disease was discovered, doctors tried to classify patients based on their symptoms. The disorder usually is divided into three types, although Sidransky says she has observed so many atypical presentations that she now considers the disease a continuum.

Before the gene responsible for Gaucher disease was discovered, doctors tried to classify patients based on their symptoms. The disorder usually is divided into three types, although Sidransky says she has observed so many atypical presentations that she now considers the disease a continuum.

The vast majority of people with Gaucher disease are classified as type 1, a variation seen most frequently in Jewish people of eastern and central European ancestry, or Ashkenazi Jews. Symptoms can begin at any age and include bruising, fatigue, bleeding problems, enlarged livers and spleens, osteoporosis, skeletal deformities and sometimes lung impairment.

Dr. Sidransky calls type 1 Gaucher a "sigh of relief disease" because people with these symptoms are often told they might have cancer before a diagnosis of Gaucher disease is made. In fact, when French medical student Philippe Gaucher first described the problem in 1882, he thought he had found a form of cancer of the spleen. The true nature of the disorder wasn't understood until 1965, when the enzyme deficiency that causes Gaucher disease was discovered at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) by Roscoe Brady, M.D. Currently, type 1 Gaucher disease is treated with enzyme replacement therapy, delivered intravenously every two weeks for life at a cost of around $250,000 per year.

The most severe form of Gaucher disease is type 2, for which no treatment has so far been successful. Infants with this form of the disorder develop enlarged livers and spleens several months after birth, experiencing problems with movement, breathing and growth. These children suffer progressive and extensive brain and nervous system damage, usually dying before age 3.

In contrast, type 3 Gaucher disease can appear at any age. Its symptoms include all the problems seen in patients with type 1 Gaucher disease, as well as brain and nervous system involvement. While enzyme replacement therapy is useful for the type 1 symptoms, no treatment to date has had any effect on type 3's neurologic difficulties.

Gaucher disease affects men and women equally. About 20,000 people in the United States have type 1, and about 4,000 are receiving treatment. Types 2 and 3 are much rarer, and only a few thousand cases have been reported worldwide.

Dr. Sidransky and her colleagues at NIH are considered leaders in the Gaucher disease research community. Not only was the enzyme deficiency responsible for the disorder discovered at NIH, researchers at NIH also pinpointed the GBA gene, identified the first mutations in GBA associated with Gaucher disease, developed the first enzyme replacement therapy for the disorder and initiated the first gene therapy studies for Gaucher disease.

NIH scientists also created the first mouse model that mimics the disease, paving the way for efforts to study the problem more closely than is possible in humans. Using these mice, Dr. Sidransky discovered a previously unrecognized form of type 2 Gaucher disease in which both mice and humans develop a cellophane-like membrane over their skin when in the uterus and die either before or shortly after birth.

Dr. Sidransky and her colleagues are eager to share their knowledge and expertise with other researchers, as well as to raise the profile of the disorder in the medical community. "Even though you can make the diagnosis from a blood sample, many patients must endure painful bone marrow or liver biopsies before Gaucher disease is identified," said Dr. Sidransky. "That is one of the reasons greater physician awareness is so important."

Dr. Sidransky understands this lack of knowledge because she only began working on Gaucher disease by chance. A pediatrician by training, she became interested in genetics in the late 1980s and applied for a fellowship at NIH to study clinical genetics and molecular biology in a way that was relevant to disease. As her mentor, she selected Edward Ginns, M.D., Ph.D., former chief of the Clinical Neuroscience Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health, who happened to be investigating Gaucher disease. He and his research group had just cloned the GBA gene and found the first Gaucher mutations, so it was an exciting time to join the team.

After she became a senior investigator at NIH, Dr. Sidransky continued her pursuit of Gaucher disease. She views her approach to research as a two-way street: sometimes her experience in the clinic drives the research and sometimes her research determines what she explores in the clinic.

Her current work focuses on understanding why each GBA mutation can produce such a wide array of symptoms. She thinks that interactions between glucocerebrosidase and other genes or proteins may be responsible, and her laboratory is searching for these potential partners. She is also looking into new treatments for the disease that are more effective, less costly, easier to administer or that can prevent or lessen neurological symptoms.

In addition, Dr. Sidransky is exploring a link between Gaucher disease and a far more common disorder, Parkinson's disease. Gaucher disease patients with unusual problems are often referred to the NIH, and one of these patients also had symptoms of progressive Parkinson's disease. When Dr. Sidransky and her colleagues at other institutions looked at their patient pools more closely, they found more people with signs of both disorders. They also discovered that people with Gaucher disease had more relatives with Parkinson's disease than the general public. Dr. Sidransky's lab searched for GBA mutations in brain samples of patients who died of different forms of Parkinson's, and discovered them in about 10 percent of this population.

"I'm currently studying older adults with Parkinson's disease because that is where the story has taken me," Dr. Sidransky said. "Only a small number of patients with Gaucher disease also have Parkinson's disease. Their Parkinson's symptoms can be mild to severe, and treatment responses differ widely as well. Although one problem does not cause the other, there is definitely a connection and we are trying to discover what it is."

Dr. Sidransky finds the link between the two diseases a rewarding example of how studying a rare disorder can produce insights that help people with far more common illnesses. "The more deeply you study this dual problem, the more variations in the symptoms, the mutations and the disease course you find," she concluded. "You never know where these studies will lead."

Last Reviewed: March 13, 2012