-

Video Post: Chilean Teacher Shares IceBridge Experience

-

Posted on Nov 09, 2012 09:14:51 AM | George Hale

0 Comments

| Permalink

|

-

By George Hale, IceBridge Science Outreach Coordinator, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

On Nov. 1, 2012, two science teachers from Punta Arenas, Chile, accompanied IceBridge researchers on a survey flight over Antarctica. Below are videos from one of these teachers, Mario Esquivel of the Colegio Francés (French School) in Punta Arenas.

The first video, Operación Icebridge en Antartica 2012 (Viaje Profesores Chilenos con la NASA), shows photographs Esquivel took during the Nov. 1, 2102 survey of the Ronne Ice Shelf.

The second video,

Xchat between NASA Icebridge from DC-8 over Antarctica and Colegio Francés Punta Arenas Chile, shows photographs from a Chilean classroom and quotes from online chat question and answer sessions between students and IceBridge personnel on the NASA DC-8.

Video showing students communicating with IceBridge personnel on the NASA DC-8 via online chat. Credit: Mario Esquivel

-

Scientific Snapshots: Using IceBridge Data in the Field

-

Posted on Nov 08, 2012 10:20:05 AM | George Hale

0 Comments

| Permalink

|

-

By George Hale, IceBridge Science Outreach Coordinator, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Every IceBridge flight adds to a growing collection of geophysical data. Gigabytes of information on surface elevation, ice thickness and sub-ice bedrock topography are collected, but collecting the data is only the beginning of the job. After each campaign, information is downloaded from the instruments and processed to be delivered to the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Colorado, who store IceBridge data and make it freely available to the public.

Preparing data to send to NSIDC is a long and painstaking process, usually taking about six months. Before even starting data processing for the Airborne Topographic Mapper, IceBridge's laser altimeter instrument, it's necessary to calculate aircraft position and attitude and even mounting biases on ATM's laser itself. "Once all the calibrations take place, the processing of all the ATM lidar data can take place," said ATM program manager Jim Yungel. After that, processing to remove returns from clouds and ice fog and quality checking takes place. And because there are two ATM lidars, one narrow-band and one medium-band, this process is done twice and the results are compared.

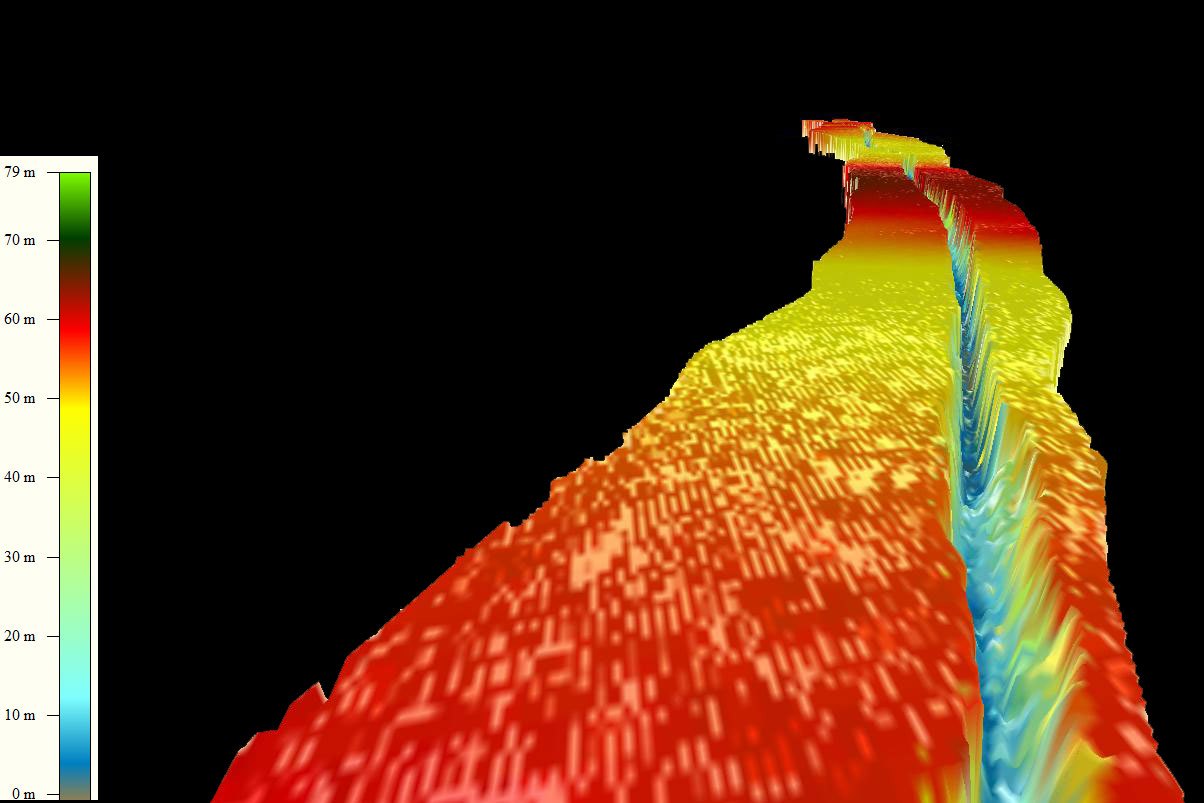

But sometimes researchers want a visual representation of something interesting in the field. By combining lidar data with rough GPS trajectories and information from the aircraft's inertial navigation system, researchers like Yungel can use a custom-built graphics program to create visual representations of the ice. These snapshots of the surface aren't meant to be precise, but to give IceBridge scientists a rough idea of what was seen, and when combined with images from the aircraft's Digital Mapping System, it's easy to see side-by-side, a representation of what information the instruments collect. Below are a few representations of features seen during 2012 Antarctic campaign flights.

A graphical representation of processed Airborne Topographic Mapper data from the 2011 Antarctic campaign showing the rift in Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier. Credit: NASA / ATM Team

Animation showing a 2012 ATM data representation of Pine Island Glacier rift and images from the Digital Mapping System. Credit: NASA / ATM and DMS teams

Crevasses in a glacier seen from the DC-8 near the Ronne Ice Shelf on Nov. 1. Credit: NASA / Jim Yungel

ATM data representation of the glacier crevasses seen on the Nov. 1, 2012 flight. Credit: NASA / ATM

-

IceBridge Guests Get Behind the Scenes View

-

Posted on Nov 05, 2012 08:12:13 AM | George Hale

0 Comments

| Permalink

|

-

By Maria Jose Viñas, Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory Outreach Coordinator, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

We sure had a packed plane on today’s flight, with visitors from the U.S. Embassy in Santiago, the Nathaniel B. Palmer, a Punta Arenas newspaper and two local schools. The Chilean teachers are the first to ever accompany IceBridge on an Antarctic mission (five docents had a chance to go on Arctic flights last spring). Carmen Gallardo, who teaches biology at Punta Arenas’ Colegio Alemán (German School) to kids ages 13 to 18 and Mario Esquivel, an astronomy teacher for students ages 9 to 14 at the local Colegio Francés (French School), were selected by the American Embassy in Santiago to fly on the DC-8 based on their English skills and, more importantly, on their plans to share their IceBridge experience with their classrooms and colleagues.

Visitors to IceBridge prior to a survey flight on Nov. 1. Credit: NASA / Maria Jose Viñas

“From the point of the U.S. Government, what we want the most is to reach the Chilean youth – and we do it through their educators," said Dinah Arnett, public affairs representative from the U.S. Embassy in Santiago.

Arnett was impressed with the enthusiasm and commitment of both teachers: they thoroughly researched the IceBridge mission beforehand and patiently went through two last-minute flight cancellations. But, as Gallardo said after yesterday’s flight was scrubbed: “Third time’s the charm!”

At the end of the almost 12-hour flight, both teachers were in awe of the sights they had enjoyed over the Antarctic Peninsula and the Ronne Ice Shelf during the Ronne Grounding Line mission. And they both thanked the researchers for their willingness to share their science. In turn, the educators plan on spreading the IceBridge word: both will be creating multimedia exhibits and giving talks to students from and beyond their schools.

IceBridge project scientist Michael Studinger and Chilean teacher Mario Esquivel looking at a map on the NASA DC-8. Credit: NASA / Jefferson Beck

Columbia University geophysicist Kirsty Tinto explains the science behind the gravimeter instrument. Credit: NASA / Jefferson Beck

-

Port of Inquiry: IceBridge visits the Nathaniel B. Palmer

-

Posted on Oct 30, 2012 09:48:21 AM | George Hale

0 Comments

| Permalink

|

-

By George Hale, IceBridge Science Outreach Coordinator, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

With its proximity to the Antarctic Peninsula, Punta Arenas, Chile, a city on the Strait of Magellan in southern South America, is a popular destination for scientists on their way to Antarctica. Not only

does NASA's Operation IceBridge use the Punta Arenas airport as a home base

during its Antarctic campaign in October and November, the city is also a base of operations for a variety of Antarctic science missions. During this year's Antarctic campaign, the IceBridge team got to take a close up look at the United States Antarctic Program's

icebreaker Nathaniel B. Palmer, which calls Punta Arenas home.

On Oct. 24, Jamee Johnson and Chris Linden of the United States

Antarctic Program led a group of IceBridge personnel on a guided tour of the

Palmer. The research vessel is waiting in the port of Punta Arenas until late

December or early January, when it will carry scientists and their equipment to

McMurdo Station in Antarctica, conducting experiments along the way. Once there, passengers will

offload and a new group of people and gear will board the icebreaker for a return

trip to Punta Arenas.

IceBridge personnel on the dock in Punta Arenas in front of the Nathaniel B. Palmer. Credit: NASA / Christy Hanse nand USAP / Jamee Johnson

The Palmer is a 6,500 ton icebreaking research vessel that

travels to and from bases in Antarctica like United States' McMurdo Station.

The vessel sails from one of its home ports, like Punta Arenas, carrying scientists who do research along the way. During the

tour, IceBridge personnel got to see some of the ship's five labs, the galley,

the infirmary and the ship's bridge, where they met Sebastian Paoni, captain of the Palmer since

2007.

Palmer Captain Sebastian Paoni (right) meets visitors on the bridge. Credit: NASA / George Hale

In many ways, the

Palmer is similar to other large, ocean-going research ships. There are places

for crew and passengers to sleep, eat, relax, exercise and socialize. With

trips to sea lasting several weeks at a time, ships like the Palmer need to be

self-contained floating cities, carrying enough food, water, spare parts and

other supplies needed to keep the crew and passengers safe and happy.

The big difference between the Palmer and other research vessels is that it has a reinforced hull designed to let it break through ice, opening a passage to travel through. There are limits to how thick of ice the ship can break through, so planning the ship's route often requires satellite imagery and other data that can show where thinner ice is. Sailing through ice is a slow and often noisy process, but when your path is blocked by sea ice, slow and noisy beats not at

all.

Science By Air and Sea

The Palmer and IceBridge's aircraft both gather geophysical data, and despite the different nature of these platforms the instruments have some similarities. In the labs, Linden, a senior systems analyst

aboard the Palmer, showed IceBridge team members several different instruments, such as including a gravimeter and a sonar system used to map the ocean floor. The

sonar uses a technique to create swaths of data that resemble the

swaths of elevation data produced by IceBridge's Airborne Topographic Mapper

instrument.

Probably the biggest similarities are dealing with motion and the changing array of instruments used. Scientists need to counteract motion from either a rolling ship or vibrating airplane, which is handled in both cases by referencing the instruments with data from GPS and inertial guidance systems. Also, much like on NASA's aircraft, the instruments on the Palmer change depending on what is being studied. Changing the configuration of the ship's equipment is something Johnson said is one of the most interesting parts of the job.

In return for graciously taking visitors on a tour of the ship, IceBridge invited some Palmer personnel to come along on a survey flight. People working on icebreakers rely on information about sea ice to plan their routes and although IceBridge data isn't directly used, flying along will give them a chance to see how the mission measures ice from the air.

Palmer visitors stand on the helipad on the Palmer's stern. Credit: NASA / Christy Hansen and USAP / Jamee Johnson

For more information about the Nathaniel B. Palmer, visit: http://www.usap.gov/usapgov/vesselScienceAndOperations/index.cfm?m=4

-

A Diplomatic Visit for IceBridge

-

Posted on Oct 28, 2012 07:50:03 AM | George Hale

0 Comments

| Permalink

|

-

By George Hale, IceBridge Science Outreach Coordinator, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

On Oct. 25, IceBridge was joined by U.S. Ambassador to Chile Alejandro Wolff and his Secretary for Economic Affairs Josanda Jinnette. Ambassador Wolff and Ms. Jinnette traveled from Santiago on Oct. 24 and attended IceBridge's evening science meeting that day. The following morning, they sat in on the morning pre-flight meeting and after a short safety briefing they boarded the DC-8 for an 11-hour-long survey of the Ferrigno and Alison ice streams that empty into the Bellingshausen Sea.

In addition to being a distinguished career diplomat, Wolff is interested in science, particularly in international scientific collaboration. "Science cooperation is an important part of the U.S. – Chile relationship," Wolff said. Although this was his first flight with IceBridge, this wasn't the ambassador's first trip to Antarctica. He visited Palmer Station years ago and says that while flying over the continent isn't the same as being on the ground, it does give a better sense of its dimensions.

U.S. Ambassador to Chile Alejandro Wolff in the IceBridge operations center at the Punta Arenas airport on the

morning of Oct. 25. Credit: NASA / George Hale

Ambassador

Wolff in the NASA DC-8 cockpit shortly after takeoff

on Oct. 25. Credit: NASA / George Hale

Ambassador Wolff and Ms. Jinnette exiting the DC-8 after another successful IceBridge

survey flight. Credit: NASA / Jefferson Beck

-

Meet our wildlife liaison

-

Posted on Oct 26, 2012 09:26:34 AM | George Hale

0 Comments

| Permalink

|

-

By George Hale, IceBridge Science Outreach Coordinator, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

The newest addition to the IceBridge team is our stuffed penguin mascot. He was recently selected as IceBridge's wildlife liaison, and after training at NASA's Goddard Spaceflight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, he traveled with IceBridge scientists on the DC-8 to Punta Arenas, Chile. Our stuffed penguin mascot has been very popular with students we have done online chats with during our flights, so we've put together an introduction.

The IceBridge mascot aboard the NASA DC-8. Credit: NASA/Michael Studinger

What is your role with Operation IceBridge?

I'm the IceBridge wildlife liaison and mascot. Animals that live in Earth's polar regions, especially penguins, find it annoying when planes fly over too low. Because of this, IceBridge works hard to avoid areas where penguins live. We work with the National Science Foundation and a group in the United Kingdom called Environmental Research Assessment to carefully plan our flights, and I'm able to give a penguin's point of view on things. I'm also in charge of keeping people happy during the 10 to 12-hour-long flights over the Antarctic so they do their best work.

How long have you been with NASA and IceBridge?

I started working for NASA only a few weeks before the start of our Antarctic campaign. After being hired I started my training at Goddard, and rode to work with IceBridge's project manager Christy Hansen. After a few weeks of hard studying I was ready to start flying, which is something penguins almost never get to do.

Where are you from originally?

My family originally comes from South America, not far from Punta Arenas, Chile, where IceBridge flies out of. I live in Ellicot City, Maryland, now, but I hope I can get a chance to see some of my cousins while I'm in Chile. There are some penguins living just a short drive from Punta Arenas.

What led you to join Operation IceBridge?

Three reasons really. First, I want to know more about what's happening to ice in the Arctic and Antarctic. Changes to the climate in the Antarctic affect how my fellow penguins live: where they eat, where they raise their children and where they migrate every year. By working with IceBridge I can learn more about how things are changing. Second, I think it's important to avoid disturbing wildlife when doing scientific research and this is something I feel I can help out with. And lastly, because even though penguins are birds, we can't fly. I couldn't pass up a chance to fly on NASA aircraft.

The IceBridge penguin mascot using the DC-8's satellite phone headset. Credit: NASA / George Hale

What's it like flying over the Antarctic?

It's something I've dreamed about since the day I hatched. Being able to see so much of the ice from above is really cool. I've seen big glaciers, giant sheets of ice that stretch off as far as you can see and tall mountains. Seeing these things from the air when I'm used to seeing everything from on the ground and under water is amazing.

Have you seen any other penguins on the mission?

Some of the people with IceBridge went to see penguins the other day, but I was busy with work, but my new friends took lots of pictures for me. I think I'll get to go with them soon though. I won't see any from the plane though as long as I do my job right.

Editor's note: Our mascot still needs a name. Please Tweet your suggestions to our Twitter feed @NASA_ICE by Nov. 2.

-

To the Ends of the Earth

-

Posted on Oct 13, 2012 09:33:50 AM | George Hale

0 Comments

| Permalink

|

-

By Christy Hansen, IceBridge Project Manager, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

If somebody had told me that 2012 would bring with it a deployment to Greenland, Chile, and possibly Antarctica, I never would have believed them. But here I am reflecting back on my three weeks in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, as I pack for Punta Arenas, Chile. These experiences have been made possible by my new assignment as the project manager of a NASA airborne geophysical project called Operation IceBridge (OIB).

Christy Hansen in Kanger, Greenland, after one of Operation IceBridge’s science flights. Behind her is the air traffic control tower, as well as the P-3B propellers. Credit: Christy Hansen

I started full-time work with OIB this past March. What I truly enjoy about this project is the remarkably talented and extensive team I work with. As the project manager, I must coordinate and help lead a vast team of experts spread out across the country. This team includes polar scientists, instrument engineers, educational/outreach teams, logistics teams, data centers, and aircraft offices. I have to utilize good leadership and communications skills to help my integrated team work together smoothly to achieve a common goal and meet all of our science objectives.

Christy Hansen stands in front of an airplane at Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia. This plane took her to Greenland this past April. Credit: Matt Linkswiler

Twice a year, the OIB team travels to Earth’s polar regions to collect data on the changing ice sheets, glaciers, and sea ice. For the Arctic campaign, we use the P-3B 4-engine turbo-prop airplane at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center's Wallops Flight Facility. It has been modified to carry nine different science instruments, including laser altimeters, which measure the different heights of the terrain from aircraft, and various types of radar systems that can actually penetrate the thick ice sheets.

Just four weeks after I started as project manager, I found myself landing in a small Southwestern Greenlandic town called Kangerlussuaq. There was snow on the runway and everyone was bundled in coats. The majority of the buildings looked like military barracks. Most of the OIB team was already there, and they greeted me at the plane. At the time, I knew only one person, the project scientist, and we had only spoken a few times! What an adventure awaited me!

A view of sea ice with open leads of water. Credit: Christy Hansen

An image of a glacier’s calving front, where it flows and loses ice to the sea. Credit: Christy Hansen

Each day, we flew at 1500 feet, seemingly scraping the surface of the massive Greenland ice sheet. I felt as though I could have touched it with my fingers if I had just stretched out my hand. It was beautiful.

Watching the team work together like a well-oiled machine, for almost 8 hours at a time, was simply awesome. The pilots, the aircraft maintenance team, and the instrument experts, who collect gigabytes and terabytes of data per flight, collect the invaluable data that tells us what is happening at our poles, and how much the ice is changing each year.

The plane flies over sea ice. The P-3B propeller can be seen out the window of the plane. Credit: Christy Hansen

Christy Hansen sits on a toolbox while she working on the Operation IceBridge flight. She is surrounded by various scientific instruments. Credit: Christy Hansen

My second trip to collect data with the OIB team began last September. For the Antarctic campaign, we use NASA Dryden Flight Research Center’s DC-8 aircraft and operate out of Punta Arenas, Chile. During this Chilean campaign, we will actually fly from Chile, over specific science target regions in Antarctica, and then land back in Chile! That’s an 11-hour round trip flight almost every day!

Christy Hansen hugs the Russell glacier, part of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Credit: Christy Hansen

Isn’t this exciting? If you want to learn more about what I do and Operation IceBridge’s current Antarctic campaign, join my Google+ Hangout on Wednesday, October 17th from 1-2pm EST. I look forward to talking to you from Chile.

Editors note: This feature was originally posted on NASA's Earth Science Week Blog.