On the Outside

“Here’s one from Delilah!” Richard, my little summer student, calls to me as I sweep the yard with my eyes and walk over with my shovel to where he is standing, pointing to a pile of dog-doo which we are cleaning up in preparation for my summer writing camp. Hot as it’s been we will still have our recess out here in the yard, and I can’t have the children stepping into anything as unpleasant as dog poop, even though the Great Gulf Coast Hot, as I think of it, emanating from the damp, fetid, feminine crotch of this animal-shaped continent, dries it into crumbly, scentless husks almost immediately, and renders it harmless. Richard has been to my house before and knows my animals. Delilah, the sheltie, has considerably smaller, more compact turds than my big yellow lab, Genevieve. Genevieve’s are easier to spot, but not so easy to pick up.

This is all very different from the dog poop of my youth. I grew up in Washington state in the sixties. There were four seasons and real, green grass grown from seed, none of this St. Augustine weed. Dog poop stayed brown and soft for a long time, darkening the already green grass into fertilized, verdant islands that dotted the lawn. Memories of my childhood in Washington spring up daily, unbidden, still, and I expect, they always will.

I pause and look at my yard with the flowers drying up in this god-awful heat and drought. It still makes me happy to survey this property and know that it is mine, humble and in Houston though it may be. The house is just an old piece of junk, but it’s been lovingly cared for and repainted, some flower boxes added to the windows, and it’s quite charming and interesting now. It’s my old piece of junk, and I love it.

I still wonder at the success of my summer programs. I began a creative writing workshop four years ago in a desperate effort to supplement my teacher salary. I never meant for it to be anything else. Now, here I am, with parents clamoring to get their children into one of my four classes, and more work than I really want during my cherished summers. I accept children from kindergarten through fifth grade. To say that I don’t always feel like I know what I’m doing is an understatement. Why do parents seem to have such faith in me? How did that happen?

My mother was a teacher, as was her mother and father and their parents too. I have brilliant uncles and cousins who retired from their high-paying jobs in the science/engineering/medical professions in order to teach. None of them cared about anything like tenure, they just were compelled to teach, so they did. It seems to be embedded in our genes, this teaching business. Maybe I’m just a natural. . . but no, there’s more to it.

My mother would never have held a private workshop at her house, but those were different times. We kids ran wild and free, in packs, all summer long. A few may have received private piano or dance lessons, and some of us may have even gone to a camp, but it would have been a real camp, somewhere in the mountains, with cabins and sleeping bags and a mess hall. My mother had a sense of her innate boundaries and wouldn’t suffer a student or the parent of a student looking her up in the phone book and calling her at home, that’s not to say that she never compromised those boundaries. You never knew when she would bring one of her poorer students home for us to play with while she found the child some hand-me-down clothes.

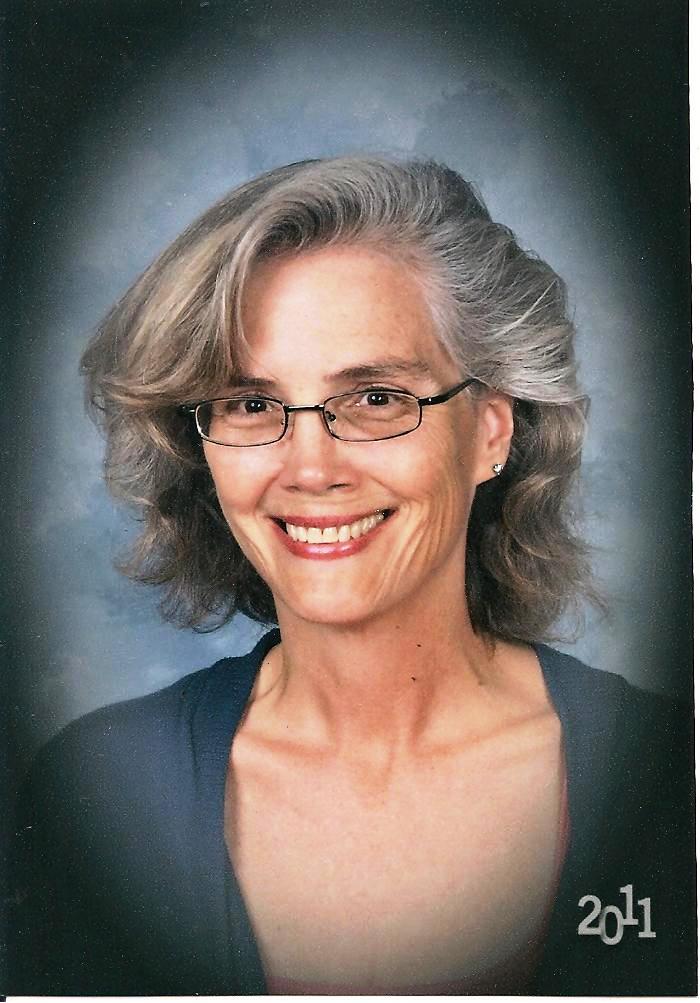

I loved my mom and never took her for granted. She had black curly hair and pale, creamy skin, and with her signature red lipstick, my sister and I thought she looked like Snow White or maybe Elizabeth Taylor. I never got into trouble because I couldn’t stand the thought of her disapproval, or of breaking her heart.

The one object I remember best when I think of my mother is her white, terrycloth bathrobe - the look, feel, and smell of it. Her face is a hazy blob for some reason, but I remember every detail of that robe. Many mornings I would get up early to find her blessedly alone in the kitchen, fixing our large, blended family the morning pot of oatmeal and drinking tea. “Morning Mama,” I would say and run into her arms. I can still feel the roughness of the terrycloth on my cheek, and smell her warm smell. Out we would go to the front porch in time to see the Washington sun rising over the mountains in the east, streaking the desert sky purple and pink before lightening it to a brilliant blue. I knew as sure as I was alive and standing on that porch that that sun would follow its arc along the Columbia River, which flowed in a perfect east/west direction below the bluffs behind our house, before it set behind Rattlesnake Mountain in the west. These were my stolen moments with my beautiful, but distracted mother, and we needed no words.

I was on the uneven parallel bars in my seventh grade PE class, and Mrs. Carlson was having me demonstrate a rather complicated dismount. Teachers often used me as a model, in every class, but on the bars I was in my element, proud and confident, when the vice principal, Mr. Eiredam, came to the door of the girls’ gym, where no men were usually allowed. He and Mrs Carlson told me to get down and called my step-sister, Frieda, and I to the locker room to change into our regular clothes. I knew immediately that something was up. I kept saying, “Just tell me what’s wrong!” But no one would look me in the eyes. Mr. Eiredam drove us to Aunt Retha’s house (our family friends), trying to act like nothing was unusual. He kept tapping his hand against the back of the front seat of the old Buick, in time to the music he had turned up in an effort at acting nonchalant. I sank back into the old upholstery and felt like the earth was swallowing me whole. No one spoke. We saw our next door neighbor’s black Chevy parked in front. What in the world were they doing here? The air around me became heavy and oppressive, and taking a step was curiously and absurdly difficult. I no longer wanted anyone to speak; I didn’t want to know.

Somehow we got inside the house. Aunt Retha was crying and when she said, “Your mother has been killed,” I collapsed on the floor. But it wasn’t any better down there. I looked around at the crowded room; at the neighbors standing awkwardly in a corner, at a loss as to what to do, my step-father, Fred, who was intermittently crying and talking on the phone, but who still seemed to retain his natural power and control, my step-sisters, whose tear-stained cheeks seemed so insufficient to this catastrophe, and my sister, Janie, whose nylons were strangely shredded. She had run through the sage brush trying to get help after the train dragged the Plymouth she was riding in with our mother off the road. Someone was crying, “No, no, no!” and I realized with a shock that it was me.

I got up and went outside in an effort to find some air, but something weird had happened to the horizon. My love of the mountains and rivers and seasons had always been a natural connection, but suddenly the horizon was no longer the same; it was not horizontal, but tilted, at a slant. Nobody else seemed to notice that the world wasn’t right, and that was as disturbing as anything.

From that moment on I had to learn to stand on the world differently, walk through my life at an angle. My prowess in gymnastics would serve me well. Yet my sense of direction has remained messed up to this day. I can’t seem to find my way anywhere, even with a GPS.

As we continue combing my yard, my mind wanders to the previous week and the exceptional group of first-graders with which I’ve just finished. Ramiz, my moody little rager, no longer throws tantrums like he did at the beginning of the year. An accomplished rager, myself, I so understand that tantrum stuff. Actually, I understand most everything my kids present me with. I think my favorite girl this past year was Lily, my little brilliant gymnast. I will miss the way she stood to take her spelling tests, right foot raised high behind her in a perfect arabesque, but head tucked obediently behind her carrel, brow furrowed, concentrating. My favorite boy was Silas, truly an exceptional child, but he always had to be first. He would never use the Boys’ room during our restroom breaks just so he could be the first one in line. He’d hold that pee all day long. I so get that too. I made the mistake of making Silas cry early in the year, and it about killed me. Not that I’m opposed to making children cry, mind you, but not this one. Tears are not something that he shares freely or easily, like most children do. I went out of my way never to do that again. Then there was Alex, with his exaggerated version of even the most mundane event. He’s probably been the most difficult one to like this year. I can’t stand lying in a six-year-old. The thing is, I understood them all, nothing ever fazes me. There is no experience that they can bring me that can shock me. Margaret loved me so much that she liked to take things from my desk and turn off the computers when I was not looking. She was a regular stalker. I have that t-shirt too.

The petunias and the ivy in the window boxes look spectacular to me as Richard and I set out pencils and journals on the picnic table. My cluttered mind hurtles me back to another memory of a place with hanging plants, and I am somewhere in 1998, in my old house in Montrose, stumbling around the kitchen while my baby girl sleeps in the other room. It was mid-morning, but I was already too drunk. I hadn’t paced myself properly. Earlier in the day I had found the unexpected prize of a frozen bottle of Stoli in the un-defrosted freezer, and I had almost polished it off. It was not like me to forget about a bottle, especially Stoli, which was a little more expensive and a rare treat. I decided to call my step-father, Fred, with whom I hadn’t spoken for years. We all knew why, even if no one wanted to talk about it. So I called him, in what felt like a perfect moment of bullet-proof clarity, thinking that he was going to be thrilled to hear from his long-lost daughter. This time, I was sure he would own up to the incest and apologize. Of course it didn’t go the way I imagined. He denied it all. I sat down hard and stupidly on the dirty kitchen floor, bottle of vodka in one hand, dead phone in the other. I was truly puzzled.

My bullet-proof haze of vodka-induced grace faded, and I was suddenly angry, humiliated. How did I get here? I began looking for the half-pint of Smirnoff that might have been hidden in the utility drawer. It wasn’t there. I would have to figure something out, get to the liquor store somehow, but which was the next one on my circuit? I had to be careful and weigh things against one another, like not wanting liquor store owners to know what a drunk I was by showing up too soon, again, with how quickly could I get there and back without the baby waking up. Or maybe, I thought, I should take her with me?

What I did find was my Big Book from Alcoholics Anonymous. AA-ers! What do they know? And who wrote that hideous book? How was I supposed to get sober if I had to read bad writing like this? Surely Bill W. and Dr. Bob could have found someone who could write better than this to reach all the drunks in the world. I’m way too smart to read this stuff, I thought, as I stumbled drunkenly around the room. I was also way too low on the pint which I was swinging around and taking long pulls off of as I paced and imagined brilliant conversations with various people in my life.

Fairway Liquor – that’s where I’d go next. That weird little Vietnamese guy who ran it and owned it would just gaze inscrutably at me when I went in there. He would never say a word to me, just hold up a pint of Smirnoff in one hand and a half pint in the other, letting me choose by pointing which it would be. It wasn’t too far. I could get there and back inside of ten minutes. I could even bring the baby in and set her on the counter while we conducted our fast, silent transaction.

Oh here’s my problem, I thought, as I took another swig and read from the Big Book: I’m not going to be able to stop drinking until I have this spiritual experience they’re talking about. It didn’t occur to me that I was not open to any real spirituality when I was pouring such alarming quantities of false spirits into myself on a daily basis. Vodka was my god and there was no room for anything else, even though I would have argued that I was a very spiritual person, a believer in God. Alcohol sang through my veins, and I was sure my blood was pale pink with all the vodka that was mixed in with it. I no longer got sick from drinking too much. I got sick if there was nothing to drink.

This was the state I was in when the postman rang the doorbell and delivered a cylindrical mailing tube. Inside was my diploma for my recently earned Master’s degree in education. I continued celebrating, a party of one, and making my intricate plans for obtaining another bottle.

***

The arrival of my first students pulls me back to the present. These are my big kids. Most of them are going into fifth grade now and have been coming to write with me since they were first-graders. I don’t know why they want to keep coming back. There are no frills here. There is a pretty cool tire swing hanging from the water oak, lemonade, and fudgesicles. It is charming, but still. We simply write together and talk about our writing. In the summer I can actually write in my home with these kids instead of walking around monitoring them, and that delights me. I charge an outrageous fee - $200.00/week for each child for two hours every day, but it is in keeping with current tutorial rates. The pretension of it is embarrassing and causes me some anxiety, but they and their parents keep asking me for more. And I need the money, always.

When we’re done with this first day I know we will have established our routine; I have faith in the process and have learned to let it lead us. It‘s a good thing because I have so much going on today that I need not only to take it just “one day at a time,” but one moment at a time. I’m taking my lovely, sixteen-year-old daughter, Anna Rose, to a psychiatrist to see about her depression. My heart has been in my mouth over this, and I’m sweating as Dr. Silverman calls us into his office. Psychiatry and therapy have played their roles in my tattered life, but the jury’s still out as far as my opinion about it goes. I am still a loner and feel like an outcast, rather like the Little Match Girl from Hans Christian Andersen’s story, standing cold and barefoot, outside in the snow (in Houston?!), nose pressed up against the window of a sumptuous room filled with the warm and abundant lives of the golden people. Besides, as an alcoholic in long-time recovery, I am not a big believer in treating every mood plunge with a pill. We say you have to “feel your feelings”. But Anna Rose’s depression has brought me to my knees, and with all the singleness of purpose of a mother tiger, I am bent on doing whatever it takes to get my baby girl some relief, including putting her on an anti-depressant.

How can this be? I wonder. All these sober years I’ve worked so hard doing “the next right thing”, building a home and a life for us all. I have stepped back from the abyss, in recovery from a well-advanced alcoholism. I am a teacher and have earned no small amount of respect and recognition. More than anything else is the house I’ve managed to buy with my own money and work, making it into a real home, secure and comfortable with dogs and cats, books, and home-made quilts. I’ve been told that it looks like the Weasely’s house in the Harry Potter books, and that pleases me. I thought I was doing everything I was supposed to be doing, building a life for my daughter the best way I knew how, from the ruins of my own wasted past. Even if I wasn’t exactly happy, particularly with my so-called life partner, what right did I really have to expect all that? At least my daughter had a father, and I always made her my priority. Our misery didn’t matter so much, or so I thought. Wrong!

When I was drunk I used to think that as long as I could speak intelligently, without slurring (and I could do this quite well), convince you that I was okay, then everything was okay, no matter how screwed up I was or the shambles my life was in. I didn’t exist except in the impression I could create in your head. I’ve taken great pride in recognizing this about my past self and not being like that anymore. What crap! I haven’t changed at all.

“So, why are you here?” Silverman says. This guy has a powerful manner and a forceful way of coming straight to the point, and it’s a little intimidating.

“I think my daughter is depressed,” I say, very carefully, timidly. But really, this began months ago, shortly after Anna Rose began seeing, and fell in love with, a sweet beautiful boy named Gabriel. She came rushing into my bedroom one night after having spent the evening at his mother’s house. “Mom, guess what? Gabe’s aunt just read my palm!” Her enthusiasm was remarkable, and she was flushed and alive with excitement, which was all too rare with her these days, I realized with sudden awareness. This daughter of mine is lovely to look at, and in her excitement, her beauty was stunning, and I was arrested, gazing at her.

“She said that I was a romantic, but that I try to hide it, and that is so true! She said that my grandparents on the other side were unusually involved in my life, and that they were watching out for me. I didn’t really get that. Do you, Mom?”

“Yes,” I say, “I do.” And I did know what she meant. I went on listening, stunned at what she was telling me. It was as if this psychic woman, Gabe’s aunt, whom I had never met, had been reading my mail, like she was “killing me softly with her song” as Roberta Flack would have it.

“Tell me more, Sweetie.”

“I don’t know, there was so much, and I wished that I could’ve written it all down, because it made so much sense; it was so true! She said there was a shadow over my life from a father or grandfather presence. But I didn’t know who she meant. I couldn’t keep all my grandparents straight because I never knew them.”

“What else, Honey?” I whisper.

“Oh, she said that there was something wrong with my heart, that there was a pressure on it. That was the only bad thing. She said that there was a very powerful, dark force pressing on my heart, and that I needed to tell you, so that you could take me to the doctor. She said that something is very wrong, and she wouldn’t let it go. Gabe wants you to take me to have my heart checked out, but I don’t think there’s anything wrong with my heart, do you?”

“No, Anna, there’s nothing wrong with your heart, not physically. It’s something else, Honey.” Suddenly I knew it was true. There was something very, very wrong, some kind of disease of the spirit. The foreboding of a truth not yet understood washed over me like a wave. I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but her general sadness and her frustration with her weight and food rose up before me, and eating disorder! sprang to my mind as I thought, “What am I going to do? This is too much for me.” But I knew I needed to do something. All of her issues glimpsed by me in little worried moments of awareness were presenting themselves. Gabriel the angel and his psychic aunt had turned my life upside-down, forcing me to look squarely into the face of my denial to the truth of our lives through my daughter’s palm.

It occurs to me that we don’t even notice the small miracles in our lives, we’re so blind. Sometimes truth reveals itself to us in such bizarre and whimsical ways, no one could make it up as a story. I couldn’t have written a stranger piece of fiction. I remember once having a vivid dream about my cat – a lone, inside-the-house kind of cat – that she was hugely pregnant and giving birth to numerous kittens. Upon awakening I had the sure and sudden knowledge that that cat was, indeed, pregnant, impossible as that seemed. I immediately took her to the vet who confirmed the truth of my dream; the cat was in the earliest stages of pregnancy. I have never been one to ignore the knowledge that comes from dreams and other unlikely sources, intuitive that I am. This practice has never failed to serve me.

Even Anna Rose’s birth is a miracle that I’ve never understood. She came to me late in my thirties, after years of no birth control, the answer to a suddenly fervent prayer – “God, if I am meant to be a mother, please let me be one soon!” I didn’t expect it to be answered, but it was, quickly. She was born late, after I carried her for ten months, on the anniversary of my mother’s death. It’s always kept its feel of a miracle. We have always lit a Yartzheit candle on her birthday, and Gary has said the kaddish mourner’s prayer in Hebrew. Then, a few days later he does the same thing for his own father. Her grandparents on the other side . . . That would be my mother and Gary’s father. Go figure, I think. Of course. She was sent by them. Even though I have never pretended to understand this mystery, I have always felt like Anna Rose was sent to me, and that part of her mission was to save my sorry life.

A short time after the palm reading one of my student’s parents offered me the use of their beach house on Bolivar Peninsula. It was close to the end of the school year and inconvenient to go that weekend, but how could I say no to such an unexpected and rare opportunity? I decided to go and take the two lovebirds with me. It was a no-brainer. I wouldn’t have to do anything to entertain them; in fact any effort on my part along those lines would have been absurdly unwelcome. I could simply take some light reading and the quilt I was sewing and have some quality alone time by the sea, while providing my ocean-loving daughter with the perfect setting for an awesome weekend with her Gabe.

We arrived at the beach house late, exhausted because I managed to get lost on a sliver of land with only one thoroughfare – a peninsula, for God’s sake. The whole ordeal had been too much for us, and I realized that sixteen-year-olds, brilliant though they may be, are not adults and cannot be counted on as such. My daughter exploded out of the pick-up and ran screaming in the darkness towards the water. Her reaction seemed over the top to me, but I was too tired and stiff to respond. I simply said to Gabe: “She’s always been like that about the sea. Why don’t you go make sure she’s okay.” And he went, gladly.

I drew the line at the two of them sleeping in the same room, so she came to visit me in mine after tucking him in for the night. As we reclined on the bed, resting and talking, her shirt rode up and I saw a mark on her hip. “A hickey,” I thought, and then, “This has gone further than I thought,” in regard to their relationship. It was a bit of a shock because my impression had been that this love affair had been fairly chaste up to this point. Hickeys on the hip would not indicate chastity in my mind, and I resolved to talk to her about it, after I’d taken the time to process this new information. My years in AA have taught me to “pause when agitated.” I am grateful for such simple but powerful little lessons.

When we returned to Houston after this special weekend I fully expected to be lauded as the “cool mom,” riding that wave of popularity well into the summer months and beyond. This was not to be. When I approached Anna Rose, gently and lovingly, I thought, about the hickey on her hip, she screamed at me: “It’s not a hickey, Mom! We’re not having sex or anything like that. I cut myself, okay? Are you satisfied? I’m a cutter!” And with that my careful little world, built on the sands of denial, crumbled completely.

Of course, it was time to do something, but I didn’t even know where to begin. I called my friend, Anastasia, who’s a therapist and whom I know from the rooms of AA. Even though I knew Anastasia was “safe” I didn’t like to reveal too much or ask for help. But I was desperate; my heart felt like it was in a vice. In spite of my feelings I made a point of trying to act and sound rationally. That’s the thing about being a teacher: no matter how badly your life seems to be falling apart, you have to keep it together for the sake of the kids. I did confide in my partner teacher, Jennifer, because I just couldn’t keep it in, and Jen has a good ear. We understand each other, being in the trenches of school warfare and all.

As it happened, I couldn’t use either of their suggestions, but I found a path through my health insurance provider. It was through a phone call to Aetna and a visit to their website that I found Dr. Silverman. We were looking for a woman, but none of the available choices had room in their practices. Seth Silverman sounded like a good Jewish name; Anna Rose and I were instantly in agreement about this. He was also a real psychiatrist which indicated lots of education, and could provide pharmaceutical solutions if necessary. We were both open to this option. Dr. Silverman could see us, so that was the deal-breaker. We were to see him on the first day of summer vacation, the same day I would begin my summer workshops. My life was a roller coaster, and all I could do was hang on for the ride.

He launches into a litany of questions, like he has some kind of proscribed list for teenaged-girls-with-their-mothers. “In your opinion, is your daughter sexually active?”

“No,” I say, carefully, again. “Not yet, but she does have a boyfriend, and I think they are very much in love.” This fact seems to matter little to him, while I, on the other hand, am amazed at how purely these two sweet kids seem to love each other so effortlessly. Where’d she learn that, and how can she be depressed and still be able to love that way? She certainly never had it modeled for her by her father and me.

Silverman continues: “In your opinion, does your daughter drink alcohol or do drugs?”

“No,” I say, very carefully, again, “but she is the daughter of an alcoholic – me. I have thirteen years sober, and she’s sixteen. You can do the math.” I’m unable to look up at him.

“Congratulations,” he says unexpectedly. I look up, surprised. I am hardly looking for praise here, and I wave it away.

Then he’s firing off questions at me: Do I have a sponsor? How many meetings do I go to a week? Have I worked the steps? And it occurs to me again that he must be working off some obscure, approved list. It’s suddenly funny to me, and I smile. I want to say so much more, about the miraculous (to me) circumstances of this child’s birth; how she saved my life, simply by being born; that it’s complicated. But I am rendered mute by this overwhelming situation, because my string of answers sounds so bad in my ears, my life reduced to a few disconnected sentences. Finally, all I can manage to say is: “It’s not as bad as it sounds,” and “We love her so.”

He looks up at me, directly in the eye, and says: “I don’t think it sounds so bad at all.” And with that, I leave her in his hands, walking out into the waiting room with my heart lightened from the crushing guilt I’ve been experiencing, and hope washing over me like a balm on my soul, that “thing with feathers” that Emily Dickenson expresses for us so eloquently.

***

My yard is immaculately poop-free for my second group of students. I am ready as the golden people begin dropping off their children at my gate. It occurs to me that everything, all of my experience, has come together in a perfect storm to make me the teacher and mother that I am today. When a child cries at the beginning of first grade, “I want my mommy!” I understand and have to refrain from replying “Me too!” As I hug that child in an effort to comfort, I am comforting and healing myself. It’s such a revelation, and I feel so grown up, finally, after so many years.

One of the golden moms hands her daughter, Claire, through my gate and says, “Oh Ms. Rhea, please let us know if you’re doing anything else this summer or ever. Claire is just loving this!”

I’m flabbergasted, but manage to retain my poise as I say, “I’m so glad she likes it, but I don’t get it. We’re just writing.” I see the tire swing hanging close by and realize its draw.

“Don’t you know?” she replies with her radiant, golden smile. “We would follow you anywhere, Ms. Rhea. You’re the kid-whisperer.”

***

Three weeks later the anti-depressants seem to be working. My summer is busy and hectic, but do-able. The workshops and tutoring are going well. Then, Gary’s birthday arrives, and with it, another bombshell. I found a bottle of brandy in the shed that he had hidden in what he felt like was a justifiable gift to himself. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing and was virtually dumb with shock. An incredulous “How could you?” is all I could manage, as I gingerly picked up and examined the bottle, my old lover.

“It’s not that big of a deal, Sandi,” he argued back, but I could see that he knew it was a losing battle, that he was worried – a rare state of mind for him. I have drawn the line on all drinking, including his usual daily beer, since he got drunk on vodka at Christmas when his sister was here. The daily beer has been a source of contention for some time, but hard liquor has been a big NO for years. I have even gone to the extreme of telling him that I want him to talk to one of my friends in AA if we’re to stand a snowball’s chance in hell. It seemed to me that he had agreed to this, but then reneged on it. Whatever. I know he’s snuck a few beers, but there has been no obvious drunkenness in six months. I was beyond words, and he knew that I was ready to pull out the big guns and threaten to throw him out. This tactic has lost some of its punch from having been overplayed over the years. Once again, we were thrown into our familiar dance of passive/aggressive silence on my part and stony indifference on his.

As I respond to Gary with silent anger, so Anna Rose responds with disdain towards me. She is still out with Gabe at 10:30 at night after having texted me much earlier to renegotiate her curfew to 10:00. I text her angrily: “Where r u? U’r taking advantage.”

“Sorry,” she texts back. She repeats this word flippantly to me as she climbs the stairs a few minutes later, me following behind.

“Not good enough, Anna Rose. You’re not being fair.”

“You’re not being fair!” she shouts back at me.

“What would be fair?” I try to say calmly.

“I wish I could stay with him ‘til four!” she cries.

“Why are you talking to me like this? How can you treat me this way?” my voice is rising now.

“How can you treat people the way you do?” she responds.

“What are you talking about?” I’m shaking now, but we both know this is about her father. “You can just consider yourself grounded for that,” I say, turning on my heel and seething back to my own room.

“I hate you!” she screams, and the words hit me like blows. “That’s not fair! You can’t keep me away from my significant other!” And she slams her door, not once, but three times.

Impossibly, I want to giggle momentarily. Significant other?! But the situation is just too horrible.

With all this escalating physicality, Gary comes nervously up the stairs. “What’s going on?” he asks.

“This is all your fault,” I cry, my voice rough and low as I turn away.

He goes to down the hall to his daughter’s room, but gets nothing more than “Leave me alone!” screamed through the slammed door.

I am so distraught that sleep is impossible, and I have eight students coming in the morning. I can’t even think about that, that’s the door to true hell. I’ll make it, somehow. I always do. This isn’t the first time a scene like this has played out. I remind myself that I used to have to wait tables after being up all night on cocaine and vodka. I can do anything. In the wee hours of the morning I just give up. There is no obvious answer. I am powerless over this. I finally sleep. When I wake up in the morning, I think of Dr. Silverman and wonder if he can help us all. He seems to have had some success with Anna Rose. It is so clear to me that we all need help. We are a family, but we’re not functioning. We’re just limping along, and Anna deserves better than that. We all do. Perhaps, once more, it will be this daughter of mine who will lead me to salvation.

I’ve often heard it said, in and out of the rooms of AA, that God doesn’t give you more than you can handle. I wonder about that. It’s a comforting thought, and I certainly hope it’s true, but I have my doubts. Anyway, what is “more than you can handle”? I frequently get way more than I want to handle. I’m often overwhelmed by my life. I can handle a lot. This I know to be true: I am as tough as nails. It’s a fairly new realization that I’ve come to in sobriety. I don’t always feel that way, and I know people don’t perceive me that way, but I am tough. So when I’m told that God won’t give me more than I can handle, I think: “So? What does that mean?” After all, what’s the alternative?

My summers are often fraught with grand epiphanies and “growth opportunities.” It’s like God, or the universe, or what have you, is just waiting until I have time to “handle it.” This summer is proving to be typical in that regard. I should be grateful for all this awareness, this chance to make things better, but really I’m just scared. For all of my toughness and scrambling, my life never seems to measure up. I always seem to end up here at a screeching halt before the edge of a great chasm, ready to be silently swallowed whole. I think I will never be one of the golden people, which is fine with me. But I would like to live a golden life, and that seems to be forever out of my reach. At the very least, I would like to be able to give that life to my daughter, and I’d like her to love me, always. But who knows? At this point I wonder if she’ll even want to come home, ever, after she’s grown.

It is in this state of mind that I go shopping, one of my many strategies for temporarily filling the Great Void in my soul. I have a few bucks left on my Coldwater Creek credit card. I find a pale green summer cardigan and a charcoal t-shirt dress for forty percent off. At the checkout counter I see a bowl of river rocks with words engraved on them. The word “Hope” jumps out at me against the perfect white smoothness of the stone on which it is inscribed. I hold the rock in my palm and feel it’s smooth weight and ancient promise of longevity. I see the river that rushed endlessly across it. Hope, I think. Yes. It’s what I always tell my students. “You must never, ever give up hope, boys and girls.” That and “Just do the next right thing, and your lives will unfold in grace. Don’t you want to live in grace?”

“Yes, Ms. Rhea,” they always say solemnly, eyes wide. And then they often remind me of my own words by repeating them back to me throughout the year.

I pay the $5.95 for the stone, impulse buyer that I am, and walk out into the bright, but oppressive Houston sunshine and heat, somewhat lifted. Is it my temporary fix of retail therapy? Is it the Hope stone? Wryly, I don’t really know. But the stone stays with me and feels good in my hand, all day long. The feeling of hope flutters feebly in my heart and refuses to fade. I hold onto that feeling as I squeeze the rock.

-Sandra Rhea