Goal

Promote the health of people with disabilities, prevent secondary conditions, and eliminate disparities between people with and without disabilities in the U.S. population.

Because disability status has been traditionally equated

with health status, the health and well-being of people with disabilities has

been addressed primarily in a medical care, rehabilitation, and long-term care

financing context. Four main misconceptions emerge from this contextual

approach: (1) all people with disabilities automatically have poor health, (2)

public health should focus only on preventing disabling conditions, (3) a

standard definition of “disability” or “people with disabilities” is not needed

for public health purposes, and (4) the environment plays no role in the

disabling process. These misconceptions have led to an underemphasis of health

promotion and disease prevention activities targeting people with disabilities

and an increase in the occurrence of secondary conditions (medical, social,

emotional, family, or community problems that a person with a primary disabling

condition likely experiences).

Challenging these misconceptions will help to clarify the

health status of people with disabilities and address the environmental

barriers that undermine their health, well-being, and participation in life

activities. A broad array of health promotion activities are relevant to all

people experiencing a disability, whether they are categorized by racial or

ethnic group, gender, and primary conditions or diagnoses, such as major

depression, cerebral palsy, diabetes, spinal cord injury, or fetal alcohol

syndrome. The similarities among people with disabilities are as important as

or more important than the differences among clinical diagnostic groups.

Caregiver issues also have been considered, as well as environmental barriers.

Environmental factors affect the health and well-being of people with disabilities

in many ways. For example, weather can hamper wheelchair mobility, medical

offices and equipment may not be accessible, and shelters or fitness centers

may not be staffed or equipped for people with disabilities. Compliance with

the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) would help overcome some of these

barriers. A crosscutting goal is to eliminate disparities with the nondisabled

population.

The International Classification of Functioning and

Disability (ICIDH-2), developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) with

the input of numerous nations—including the United States—provides uniform

language and a framework for describing functioning, health, and disability

status among all people.[1] This framework

clarifies definitional issues and includes environmental factors.

An estimated 54 million persons in the United States, or

nearly 20 percent of the population, currently live with disabilities.[2] Data for the period 1970 to 1994 suggest

that the proportion is increasing.[3] The increase in

disability among all age groups indicates a growing need for public health

programs serving people with disabilities.

From 1990 to 1994, disability rates increased among youth

under age 18 years.3

There was a 33 percent increase in activity limitations among girls, from 4.2

percent to 5.6 percent, and a 40 percent increase in activity limitations among

boys, from 5.6 percent to 7.9 percent.

Among adults aged 18 to 44 years, there was a 16 percent

increase in activity limitations, from 8.8 percent in 1990 to 10.3 percent in

1994.3

This increase suggests that 3.1 million more people aged 18 to 44 years were

limited in 1994 than in 1990.

The absolute number of adults aged 65 years and older with

disabilities increased from 26.9 million in 1982 to 34.1 million in 1996. Because the total number of adults aged 65

years and older increased even faster, the proportion of those with

disabilities declined from 24.9 percent in 1982 to 21.3 percent in 1994.3

However, the rise in numbers indicates a growing need for programs and services

to serve this older population.

The direct medical and indirect annual costs associated with

disability are more than $300 billion, or 4 percent of the gross domestic product.[4]

This total cost includes $160 billion in medical care expenditures (1994

dollars) and lost productivity costs approaching $155 billion.

The health promotion and disease prevention needs of people

with disabilities are not nullified because they are born with an impairing

condition or have experienced a disease or injury that has long-term

consequences.[5] People with

disabilities have increased health concerns and susceptibility to secondary

conditions. Having a long-term condition increases the need for health

promotion that can be medical, physical, social, emotional, or societal.

People who have activity limitations report having had more

days of pain, depression, anxiety, and sleeplessness and fewer days of vitality

during the previous month than people not reporting activity limitations.[6]

Increased emotional distress, however, does not arise directly from the

person’s limitations. The distress is likely to stem from encounters with

environmental barriers that reduce the individual’s ability to participate in

life activities and that undermine physical and emotional health. In view of

the increased rates of disability among youth, it is particularly important to

target activities and services that address all aspects of health and

well-being, including promoting health, preventing secondary conditions, and

removing environmental barriers, as well as providing access to medical care.

For an older person with a disability, it is important to target worsening

coexisting conditions that may intensify and thus threaten general well-being.

For example, declining vision combined with declining hearing can greatly

impair mobility, nutrition, and fitness.[7]

Disability can be viewed as a universal phenomenon everyone

experiences at some time.[8]

Disability also can be viewed as representing a minority of the population, in

that people with disabilities may be less visible, undercounted, and underserved.[9]

As a potentially underserved group, people with disabilities would be expected

to experience disadvantages in health and well-being compared with the general

population. People with disabilities may experience lack of access to health

services and medical care and may be considered at increased risk for various

conditions.

Few data systems identify people with disabilities as a subpopulation.

Disparities need to be identified to plan appropriate public health programs.

Despite the paucity of data, some disparities between people with and without

disabilities have been noted. These disparities include excess weight, reduced

physical activity, increased stress, and less frequent mammograms for women

over age 55 years with disabilities.[10]

Health promotion programs that focus on improving

functioning across a spectrum of diagnoses and a range of age groups are

effective in reducing secondary conditions and outpatient physician visits

among people with disabilities.[11], [12],

[13]

For example, a focus on improving muscle tone, flexibility, and strength can accrue

benefits for mobility-impaired people in wheelchairs and mobility-impaired

people with arthritis.[14]

For people with communication disabilities and disorders, interventions can

improve access to health-enhancement programs. People with sight impairments

can have access to readable job applications, food labels, and medications.

People with hearing impairments can have access to televised or videotaped

exercise programs that are captioned or signed by interpreters depicted within

an inset of a video screen. Often, the most effective interventions may be environmental

rather than medical.

Many health promotion interventions already in place for the

population at large may be easily adapted to the needs of people with

disabilities. New strategies can be influenced by results from studies that

describe risk factors for secondary conditions or protective factors against

additional impairments. For example, the number of cases of secondary

osteoporosis among able-bodied women and their range of bone mineral density

deficits can be estimated by using existing Federal data sets. The degree to

which women exercise and ingest calcium or estrogen supplements also can be

estimated, leading to measurements of the influence of both risk and protective

factors associated with osteoporosis in the able-bodied population. Because

women with mobility impairments experience an elevated risk for secondary

osteoporosis at earlier ages, their risk factors, including diminished bone

mineral density, and their potential protective factors, including optimal

calcium or estrogen supplementation and types of exercise, become critically

important epidemiologic parameters.[15], [16] The results of investigations of secondary osteoporosis

already influence health promotion strategies among able-bodied women. Similar

investigations can augment the development of health promotion strategies among

women with disabilities.

Current guidelines provide opportunity to design health

promotion interventions targeting people with disabilities that accommodate

ongoing evidence-based evaluation[17]

and demonstrate cost-effectiveness.[18], [19] For example, clinical interventions that focus on

appropriate and timely medical care can be equally accessible for people with

and without disabilities. Mammography screening is recommended every 1 to 2

years, with or without an annual clinical breast examination, for able-bodied

women aged 50 to 69 years.[20]

This recommendation also can be adapted for women with disabilities. Clinical

providers, however, must first recognize the reasons women with disabilities

often refrain from seeking mammography services, such as the lack of adaptive

equipment on mammography screening machines or unfamiliarity with the

needs of people with disabilities expressed by clinicians. Counseling to

prevent injuries among all adults also is recommended. For example, men and

women with disabilities, especially those with skeletal insufficiencies or

calcium deficits, are at increased risk for fractures. Adding bone mineral

screening and fitness counseling during clinical encounters may be beneficial

in preventing injuries. In these ways, evidence-based health promotion and

disease prevention programs can be developed, implemented, and evaluated to

target the health and injury disparities between people with and without

disabilities.

Health promotion interventions for people with

disabilities—in the community, clinical settings, or elsewhere—should include

culturally and linguistically appropriate elements.

Healthy People 2000 did not have a chapter specifically establishing

health objectives for people with disabilities. However, some objectives

targeted people with disabilities, including leisure-time physical activity,

use of community support programs by people with severe mental disorders,

treatment for depression, activity limitations associated with chronic

conditions and back conditions, and receipt of recommended clinical preventive

services. A progress review held in January 1997 showed that none of these

specific objectives relevant to people with disabilities had been met,10

and parity with the nondisabled population will continue to be monitored.

People with disabilities reporting no leisure-time physical

activity declined from the 1985 baseline of 35 percent to 29 percent in 1995,

short of the target of 20 percent for 2000. In addition, the review noted

several disparities: 40 percent of people with disabilities aged 20 years and

older reported being overweight compared with 35 percent of the general

population and short of the goal of 25 percent; 49 percent of people aged 18

years and older with disabilities reported adverse health effects from stress

compared with 34 percent of the general population; and clinical preventive

services showed disparities for data on tetanus boosters (56 percent versus 59

percent for the general population), Pap tests (69 percent versus 77 percent of

women aged 18 years and over in 1994), and breast exams and mammograms (50

percent versus 56 percent for women aged 50 years and over).

Note: Unless otherwise

noted, data are from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Healthy People 2000

Review, 1998–99.

Disability and Secondary Conditions

Goal: Promote the health of people with disabilities,

prevent secondary conditions, and eliminate disparities between people with and

without disabilities in the U.S. population.

|

Number

|

Objective Short Title

|

|

6-1

|

Standard definition of people with

disabilities in data sets

|

|

6-2

|

Feelings and depression among

children with disabilities

|

|

6-3

|

Feelings and depression interfering

with activities among adults with disabilities

|

|

6-4

|

Social participation among adults

with disabilities

|

|

6-5

|

Sufficient emotional support among

adults with disabilities

|

|

6-6

|

Satisfaction with life among adults

with disabilities

|

|

6-7

|

Congregate care of children and

adults with disabilities

|

|

6-8

|

Employment parity

|

|

6-9

|

Inclusion of children and youth with

disabilities in regular education

programs

|

|

6-10

|

Accessibility of health and wellness

programs

|

|

6-11

|

Assistive devices and technology

|

|

6-12

|

Environmental barriers affecting

participation in activities

|

|

6-13

|

Surveillance and health promotion

programs

|

Target: 100

percent.

Baseline: No

Healthy People 2010 surveillance instruments include a standard set of

questions that identify people with disabilities in 1999.

Target setting

method: Total coverage.

Data source:

CDC, NCEH.

The call for statistics on people with disabilities is

longstanding and increasing. Various Federal agencies have attempted to collect

these data in several research areas.[21] Two separate issues exist regarding

data collection: (1) using different operational definitions of disability and

(2) not collecting information from people with disabilities during surveys.

None of the federally funded surveys attempting to collect data on people with

disabilities is using the same definition of disability. This lack of

standardization has made it difficult to (1) identify and include individuals

with a disability, (2) measure the nature and extent of disability in the

United States, (3) assess the impact of various disabilities on the person’s

ability to participate in society, (4) assess the extent of secondary

conditions among people with disabilities, and (5) identify environmental

barriers to participation and risk factors for poor health in this population.

The issue of not including people with disabilities is

reflected in the initial survey design. Most studies are not designed to

include, target, and analyze data on people with disabilities. People with disabilities

could be included as a select population if, for example, the data collection

method ensured appropriate access and outreach.

To remedy these gaps, a set of survey questions has been

developed and is being tested to identify individuals with varying degrees of

disability in terms of activity limitations.[22]

This short set of questions may be placed in the core of all Healthy People

surveillance instruments that collect demographic data to include and standardize

information on people with disabilities. On the basis of standardization and

inclusion in the Nation’s disability data collection activities, the call for

disability statistics may be satisfied. Once collected, these data will help

government policymakers, consumers and advocates, researchers, and clinicians

make better informed choices to promote the health status and well-being of

people with disabilities.

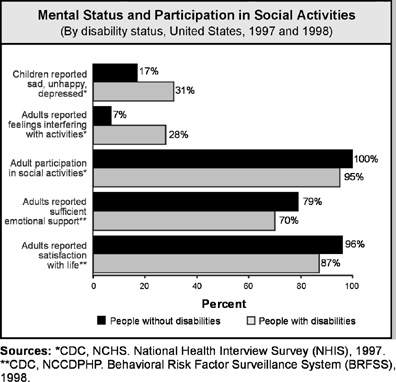

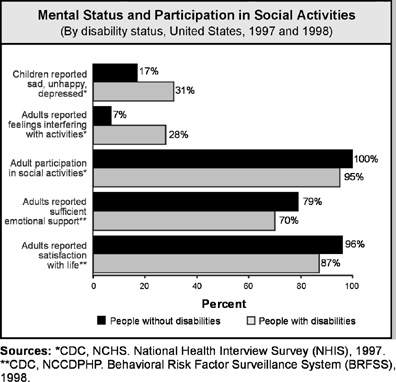

Target: 17

percent.

Baseline: 31

percent of children and adolescents aged 4 to 11 years with disabilities were reported

to be sad, unhappy, or depressed in 1997.

Target setting

method: 45 percent improvement (parity with children and

adolescents without disabilities in 1997).

Data source:

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

|

Children and Adolescents Aged 4 to 11 Years,

1997

|

Reported

To Be Sad,

Unhappy, or Depressed

|

|

With

Disabilities

|

Without

Disabilities*

|

|

Percent

|

|

TOTAL

|

31

|

17

|

|

Race and ethnicity

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native

|

DSU

|

DSU

|

|

Asian or Pacific Islander

|

DSU

|

13

|

|

Asian

|

DSU

|

16

|

|

Native Hawaiian and other

Pacific

Islander

|

DSU

|

DSU

|

|

Black or African American

|

DSU

|

16

|

|

White

|

31

|

17

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

32

|

16

|

|

Not Hispanic or Latino

|

30

|

17

|

|

Black or African American

|

DSU

|

17

|

|

White

|

31

|

18

|

|

Gender

|

|

Female

|

32

|

16

|

|

Male

|

30

|

18

|

|

Family income level

|

|

Poor

|

37

|

20

|

|

Near Poor

|

31

|

17

|

|

Middle/high income

|

27

|

17

|

|

Geographic location

|

|

Urban

|

27

|

17

|

|

Rural

|

39

|

16

|

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

*The total represents the target. Data for population

groups by race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and geographic

location are displayed to further characterize the issue.

Target: 7

percent.

Baseline: 28

percent of adults aged 18 years and older with disabilities reported feelings

that prevented them from being active in 1997 (age adjusted to the year 2000

standard population).

Target setting

method: 75 percent improvement (parity with adults aged 18 years and older

without disabilities in 1997).

Data source:

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults Aged 18 Years and

Older, 1997

|

Reported

Feelings That

Prevent Activity

|

|

With

Disabilities

|

Without

Disabilities*

|

|

Percent

|

|

TOTAL

|

28

|

7

|

|

Race and ethnicity

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native

|

22

|

15

|

|

Asian or Pacific Islander

|

30

|

7

|

|

Asian

|

DSU

|

6

|

|

Native Hawaiian and other

Pacific

Islander

|

DSU

|

14

|

|

Black or African American

|

31

|

8

|

|

White

|

28

|

7

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

40

|

9

|

|

Not Hispanic or Latino

|

27

|

7

|

|

Black or African American

|

31

|

8

|

|

White

|

27

|

6

|

|

Gender

|

|

Female

|

30

|

8

|

|

Male

|

26

|

6

|

|

Family income level

|

|

Poor

|

38

|

13

|

|

Near Poor

|

30

|

10

|

|

Middle/high income

|

21

|

6

|

|

Education level (aged 25 years and older)

|

|

Less than high school

|

34

|

10

|

|

High school graduate

|

29

|

7

|

|

At least some college

|

25

|

5

|

|

Geographical location

|

|

Urban

|

29

|

7

|

|

Rural

|

26

|

6

|

|

|

|

|

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

*The total represents the target. Data for population groups

by race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and geographic location are

displayed to further characterize the issue.

Children and adults with

disabilities and their families face issues of coping, adapting, adjusting, and

learning to live well with the disability—a dynamic, ongoing process. Good

mental health, including refusing to internalize the social stigma of

disability and developing a positive attitude and strong self-esteem, is a key

ingredient to overcoming these issues.[23]

Improving mental health status among people with disabilities and their

families will help address psychological barriers and enhance their ability to

participate fully in society.[24]

Target: 100

percent.

Baseline:

95.4 percent of adults aged 18 years and older with disabilities participated

in social activities in 1997 (age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting

method: Total participation (parity with adults aged 18 years and older

without disabilities in 1997).

Data source:

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

|

Adults Aged 18 Years and Older, 1997

|

Participation

in Social Activity

|

|

With

Disabilities

|

Without

Disabilities*

|

|

Percent

|

|

TOTAL

|

95.4

|

100.0

|

|

Race and ethnicity

|

|

American Indian or Alaska

Native

|

87.4

|

100.0

|

|

Asian or Pacific Islander

|

99.6

|

100.0

|

|

Asian

|

99.5

|

100.0

|

|

Native Hawaiian and other

Pacific

Islander

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

|

Black or African American

|

95.0

|

99.8

|

|

White

|

95.6

|

100.0

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

93.9

|

100.0

|

|

Not Hispanic or Latino

|

95.5

|

100.0

|

|

Black or African American

|

95.0

|

99.8

|

|

White

|

95.7

|

100.0

|

|

Gender

|

|

Female

|

95.2

|

99.9

|

|

Male

|

95.7

|

100.0

|

|

Family income level

|

|

Poor

|

93.1

|

99.9

|

|

Near Poor

|

95.8

|

99.9

|

|

Middle/high income

|

96.5

|

100.0

|

|

Education

level (aged 25 years and

older)

|

|

Less

than high school

|

94.1

|

99.9

|

|

High

school graduate

|

94.8

|

99.9

|

|

At

least some college

|

96.0

|

100.0

|

|

Geographic location

|

|

Urban

|

95.3

|

100.0

|

|

Rural

|

95.6

|

99.9

|

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

*The total represents the target. Data for population groups

by race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and geographic location are

displayed to further characterize the issue.

People with disabilities

report significantly lower levels of social participation compared with people

without disabilities.[25]

Participating in social activities routinely requires personal interaction with

the environment, a component of life that is vital to the well-being of all

humanity. ICIDH-2, the International Classification of Functioning and Disability,

highlights the importance of participating in social activities as a measurable

outcome of living well with a disability.1

The ICIDH-2 framework indicates that the environment should be examined as a barrier

to participation.

Social participation can

include activities such as volunteering, shopping, going to the movies, or

attending sporting events. Targeting increased participation in regular social

activities such as traveling, socializing with friends and family, attending

church or community events, and voting can result in improved functional status

and well-being.

Target: 79

percent.

Baseline: 71

percent of adults aged 18 years and older with disabilities reported sufficient

emotional support in 1998 (data from 11 States and the District of

columbia; age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting

method: 11 percent improvement (parity with adults aged 18 years and older

without disabilities in 1998).

Data source:

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), CDC, NCCDPHP.

|

Adults Aged 18 Years and

Older, 1998

|

Reported

Sufficient

Emotional Support*

|

|

With

Disabilities

|

Without

Disabilities**

|

|

Percent

|

|

TOTAL

|

71

|

79

|

|

Race and ethnicity

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native

|

56

|

72

|

|

Asian or Pacific Islander

|

49

|

66

|

|

Asian

|

DSU

|

DSU

|

|

Native Hawaiian and other

Pacific

Islander

|

DSU

|

DSU

|

|

Black or African American

|

53

|

68

|

|

White

|

74

|

82

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

44

|

68

|

|

Not Hispanic or Latino

|

72

|

80

|

|

Black or African American

|

DNA

|

DNA

|

|

White

|

DNA

|

DNA

|

|

Gender

|

|

Female

|

70

|

79

|

|

Male

|

70

|

78

|

|

Education level (aged 25 years and older)

|

|

Less than high school

|

58

|

70

|

|

High school graduate

|

74

|

76

|

|

At least some college

|

74

|

83

|

|

|

|

|

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

*Data are from 11 States and the District of Columbia.

**The total represents the target. Data for population groups by race, ethnicity, gender,

socioeconomic status, and geographic location are displayed to further

characterize the issue.

Emotional support often is

derived from a person’s social support systems. Two hypotheses suggest that

social support helps a person cope with stress and that supportive

relationships are a protective factor in various life situations.[26]

With the information gained by monitoring the personal perspective, the United

States may better meet the needs of people with disabilities.

Target: 96

percent.

Baseline: 87

percent of adults aged 18 years and older with disabilities reported

satisfaction with life in 1998 (data from 11 States and the District of Columbia;

age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population).

Target setting

method: 10 percent improvement (parity with adults without

disabilities in 1998).

Data source: Behavioral

Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), CDC, NCCDPHP.

|

Adults Aged 18 Years and Older, 1998

|

Reported

Satisfaction

With Life*

|

|

With

Disabilities

|

Without

Disabilities**

|

|

Percent

|

|

TOTAL

|

87

|

96

|

|

Race and ethnicity

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native

|

78

|

92

|

|

Asian or Pacific Islander

|

78

|

98

|

|

Asian

|

DSU

|

DSU

|

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander

|

DSU

|

DSU

|

|

Black or African American

|

83

|

92

|

|

White

|

88

|

96

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

80

|

93

|

|

Not Hispanic or Latino

|

87

|

96

|

|

Black or African American

|

DNA

|

DNA

|

|

White

|

DNA

|

DNA

|

|

Gender

|

|

Female

|

87

|

95

|

|

Male

|

86

|

96

|

|

Education

level (aged 25 years and

older)

|

|

Less

than high school

|

84

|

94

|

|

High

school graduate

|

87

|

95

|

|

At

least some college

|

89

|

97

|

|

|

|

|

DNA = Data have not been

analyzed. DNC = Data are not collected. DSU = Data are statistically

unreliable.

Note: Age adjusted to the year 2000 standard population.

*Data are from 11 States and

the District of Columbia.

**The

total represents the target. Data for population groups by race, ethnicity,

gender, socioeconomic status, and geographic location are displayed to further

characterize the issue.

Satisfaction

with life is associated with the more general term “quality of life,” which is

a personal evaluation of one’s own position in numerous dimensions of life,

including physical, emotional, social, spiritual, environmental support, and

level of independence.[27]

Monitoring the life satisfaction of people with disabilities, as well as that

of the broader population, allows an opportunity to evaluate society’s progress

in accommodating the needs of people with disabilities.

Target and

baseline:

|

Objective

|

Reduction in People With

Disabilities in Congregate

Care Facilities

|

1997

Baseline

|

2010

Target

|

|

|

|

Number of Persons

|

|

6-7a.

|

Persons aged 22 years and older

in 16 or more bed congregate

facilities

|

93,362

|

46,681

|

|

6-7b.

|

Persons aged 21 years and under in congregate care facilities

|

24,300

|

0

|

Target setting method: 50 percent

improvement for 6-7a; total elimination for

6-7b.

Data source: Survey of State

Developmental Disabilities Directors, University of Minnesota.

Many people with activity limitations

or cognitive impairments need ongoing and long-term assistance, yet some do not

require institutional care.[28]

From the 1970s through the 1990s, States began reducing the size of and closing

State institutions that served people with mental retardation or developmental

disabilities. This social, political, and economic movement resulted in a

dramatic growth in the total number of individuals served in community

residential settings—from 5,000 in 1960 to 255,117 in 1996.[29], [30] This movement,

coupled with increases in life expectancy and an expanding elderly population,

resulted in the development of several community-based and in-home assistance

programs, such as home-delivered meals, hospice care, and homemaker and

home-health services. The goal to increase home and community-based care will

broaden health and lifestyle choices for people with disabilities and their

families.[31]

Much of this expansion in community

services is funded through the Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services

(HCBS) Waiver Program, a Federal-State partnership authorized in 1981 under

Title XIX of the Social Security Act. Between 1990 and 1997, the HCBS Program

demonstrated a 25.8 percent increase in benefits per person.30

Despite this dramatic growth to support home and community-based care, in 1993,

only 11 percent of long-term Medicaid expenditures and 5.3 percent of

total Medicaid expenditures went toward community-based care.[32] The other sources of support for

community-based long-term care are Medicare, Title III of the Older Americans

Act, and the Social Services Block Grant.32

Target: 82

percent.

Baseline: 52

percent of adults aged 21 through 64 years with disabilities were employed in

1994–95.

Target setting

method: 58 percent improvement (parity with adults without

disabilities in 1994–95).

Data source:

Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), U.S.

department of commerce, bureau of the census.

|

Adults

Aged 21 through 64 Years, 1994–95

|

Employment of People With

Disabilities

|

Employment of People Without Disabilities*

|

|

Percent

|

|

TOTAL

|

52

|

82

|

|

Race

and ethnicity

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native

|

41

|

77

|

|

Asian or Pacific Islander

|

48

|

78

|

|

Asian

|

DNC

|

DNC

|

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander

|

DNC

|

DNC

|

|

Black

or African American

|

37

|

77

|

|

White

|

DNA

|

DNA

|

|

|

|

Hispanic or Latino

|

45

|

76

|

|

Not Hispanic or Latino

|

DNA

|

DNA

|

|

Black or African American

|

DNA

|

DNA

|

|

White

|

57

|

84

|

|

Gender

|

|

Female

|

46

|

75

|

|

Male

|

60

|

90

|

|

Education level

|

|

Less than high school

|

34

|

69

|

|

High school graduate

|

54

|

81

|

|

At least some college

|

63

|

83

|

DNA = Data have not been analyzed. DNC = Data are not

collected. DSU = Data are statistically unreliable.

*The total represents the target. Data for population groups

by race, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status are displayed to further

characterize the issue.

The ability to work has

implications for economic and social self-sufficiency, for full inclusion and

integration into society, and for personal self-esteem. Work and disability are

understood best within the context of a person’s abilities and the role of

accommodation, accessibility, and legal mandates. The Presidential Task Force

on Employment of Adults with Disabilities emphasized the need for a coordinated

and aggressive national policy to address the many components of work and disability.[33]

Changes in economic policies and benefits underscore the need to continue to

examine and address the structural, social, and psychological deterrents to

work for some persons with disabilities.

In 1994–95, employment rates

varied depending on degree of disability. For persons aged 21 through 64 years

with no disability, the rate was 82 percent, whereas those with a nonsevere

disability had a rate of 77 percent, and those with a severe disability had a

rate of 26 percent. Analyses of rates by gender indicate similar patterns.2

Moreover, employment patterns for persons with disabilities mirror general

social patterns of employment rates for age, race, and ethnicity.[34]

Education has a positive association with employment for all people, although

the association is strongest for adolescents and adults with a “work disability.”

Target: 60

percent.

Baseline: 45

percent of children and youth aged 6 to 21 years with disabilities spent at

least 80 percent of their time in regular education programs in the

1995–96 school year.

Target setting

method: 33 percent improvement. (Better than the best will be used when

data are available.)

Data source:

Data Analysis System (DANS), U.S. Department of Education,

office of special education.

Data for population groups currently are not analyzed. |

This objective aims to improve

the well-being of students with disabilities by encouraging academic and

learning opportunities and nonacademic social and emotional experiences that

can facilitate normal growth and development, postsecondary educational

attainment, independent living skills, and economic participation as adults.

Serving students with disabilities in regular nonspecial education classrooms

is a concern that cuts across the goals of many Federal agencies. The current

target of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services is that

60 percent of children and youth with disabilities aged 6 through 21 years

will be reported by the States as being served in the regular education

classroom at least 80 percent of the time. In support of the target, the 1997

Amendments to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act states that “to

the maximum extent appropriate, children and youth with disabilities, including

children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, are

educated with children who are not disabled.”[35]

Potential data

source: National Independent Living Centers Network.

For people with disabilities to have

the opportunity for healthy lives, both physically and emotionally, programs

and facilities that offer wellness and treatment services must be fully

accessible. Effective enforcement of the Americans with Disabilities Act can improve

services for people with disabilities and help prevent secondary disabilities.

Potential data

source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), CDC, NCHS.

In

1990, a one-time survey showed that 2.5 million people said they needed assistive

technology that they did not have.[36]

The inability to pay for such technology was the main reason given for the

unmet need. Assistive technology can be critical in the lives of people with

disabilities; thus, technology need, availability, and use must be studied.[37]

Technology can aid the independence and self-sufficiency of people with

disabilities and can enable people to work, attend school, and participate in

community life. Without assistive technology, people with disabilities may

become dependent and isolated.

Potential data

source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), CDC, NCCDPHP.

The

focus on measuring the environmental impact on people with disabilities echoes the underlying theme of the disability rights movement and the ADA.[38]

Both argue that the most important outcome for persons with disabilities—in

fact, for all persons in the United States—is their full participation as

active, involved, and productive members of society. Indeed, this participation

is the implicit outcome for the overarching Healthy People goals to achieve a

healthier life and eliminate disparities.

A

special 1999 Colorado Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey

showed that compared to 43 percent of people without disabilities, 55 percent

of adults aged 18 years and older with disabilities reported encountering environmental

barriers daily or weekly and/or barriers that were very problematic.[39]

Similar data will be collected from several other States.

Full

participation cannot be achieved without eliminating environmental barriers

found within architectural structures, technology, organizational policies and

practices, and social attitudes and without moving toward universal design and

nondiscriminatory elements. Thus public health agencies need to measure not

only the nature and extent of disability in the United States but also the

extent to which environmental barriers and universal design elements impede or

facilitate social participation.

Target and

baseline:

|

Objective

|

Increase in Public Health

Surveillance and Health Promotion Programs for People With

Disabilities and Caregivers

|

1999

Baseline

|

2010

Target

|

|

|

|

Number

|

|

6-13a.

|

States and the District

of Columbia

|

14

|

51

|

|

6-13b.

|

Tribes

|

Developmental

|

Target setting

method: Total coverage.

Data sources:

Tribal, State, and District of Columbia reports; Office on Disability and

Health, CDC.

The

needs of people with disabilities and caregivers should be addressed by public

health activities. In a telephone survey, 23 percent of all U.S. households included

at least one caregiver.[40]

While not all people with disabilities are dependent on the services of an

unpaid (usually a family member) or paid caregiver, meeting the needs of those

who benefit from personal assistance cannot be easily separated from the needs

of people who provide assistance.[41] Whether caring for infants,

children, or adults with disabilities or for the increasing number of people

who become activity-limited as they grow older, the caregiver is an important

health component.[42]

|  |

1. |

Access to

Quality Health Services |

|

|

|

|

| 1-1. |  | Persons with

health insurance |

| 1-4. |  | Source of

ongoing care |

| 1-5. |  | Usual primary

care provider |

| 1-6. |  | Difficulties or

delays in obtaining needed health care |

| 1-16. |  | Pressure ulcers

among nursing home residents |

|  |

2. |

Arthritis,

Osteoporosis, and Chronic Back Conditions |

|  |

3. |

Cancer |

|  |

4. |

Chronic

Kidney Disease |

|  |

5. |

Diabetes |

|

|

|

|

| 5-1. |  | Diabetes education |

| 5-2. |  | New cases of diabetes |

| 5-3. |  | Overall cases of diagnosed diabetes |

| 5-4. |  | Diagnosis of diabetes |

| 5-9. |  | Foot ulcers |

| 5-10. |  | Lower extremity amputations |

|  |

7. |

Educational

and Community-Based Programs |

|

|

|

|

| 7-1. |  | High school completion |

| 7-3. |  | Health-risk behavior information for college and university students |

| 7-6. |  | Participation in employer-sponsored health promotion activities |

| 7-11. |  |

Culturally appropriate and linguistically competent community health promotion programs |

| 7-12. |  | Older adult participation in community health promotion activities |

|  |

9. |

Family

Planning |

|  |

12. |

Heart Disease

and Stroke |

|

|

|

|

| 12-1. |  | Coronary heart

disease (CHD) deaths |

| 12-7. |  | Stroke deaths |

| 12-9. |  | High blood

pressure |

| 12-10. |  | High blood

pressure control |

| 12-11. |  | Action to help control blood pressure |

| 12-12. |  | Blood pressure monitoring |

| 12-13. |  | Mean total blood cholesterol levels |

| 12-14. |  | High blood cholesterol levels |

| 12-15. |  | Blood cholesterol screening |

|  |

14. |

Immunization

and Infectious Diseases |

|  |

16. |

Maternal,

Infant, and Child Health |

|

|

|

|

| 16-1. |  | Fetal and infant deaths |

| 16-2. |  | Child deaths |

| 16-3. |  | Adolescent and young adult deaths |

| 16-4. |  | Maternal deaths |

| 16-6. |  | Prenatal care |

| 16-9. |  | Cesarean births |

| 16-10. |  | Low birth weight and very low birth weight |

| 16-11. |  | Preterm births |

| 16-13. |  | Infants put to sleep on their backs |

| 16-16. |  | Optimum folic acid levels |

| 16-17. |  | Prenatal substance exposure |

| 16-19. |  | Breastfeeding |

| 16-21. |  | Sepsis among children with sickle cell disease |

| 16-22. |  | Medical homes for children with special health care needs |

| 16-23. |  | Service systems for children with special health care needs |

|  |

17. |

Medical

Product Safety |

|  |

18. |

Mental Health

and Mental Disorders |

|  |

19. |

Nutrition and

Overweight |

|

|

|

|

| 19-1. |  | Healthy weight in adults |

| 19-2. |  | Obesity in adults |

| 19-3. |  | Overweight or obesity in children and adolescents |

| 19-4. |  | Growth retardation in children |

| 19-5. |  | Fruit intake |

| 19-6. |  | Vegetable intake |

| 19-7. |  | Grain product intake |

| 19-8. |  | Saturated fat intake |

| 19-9. |  | Total fat intake |

| 19-10. |  | Sodium intake |

| 19-11. |  | Calcium intake |

| 19-12. |  | Iron deficiency in young children and in females of childbearing age |

| 19-13. |  | Anemia in low-income pregnant females |

| 19-17. |  | Nutrition counseling for medical conditions |

| 19-18. |  | Food security |

|  |

20. |

Occupational

Safety and Health |

|  |

21. |

Oral Health |

|

|

|

|

| 21-1. |  | Dental caries experience |

| 21-2. |  | Untreated dental decay |

| 21-3. |  | No permanent tooth loss |

| 21-4. |  | Complete tooth loss |

| 21-5. |  | Periodontal disease |

| 21-6. |  | Early detection of oral and pharyngeal cancers |

| 21-8. |  | Dental sealants |

| 21-10. |  | Use of oral health care system |

| 21-15. |  | Referral for cleft lip or palate |

| 21-16. |  | Oral and craniofacial State-based surveillance system |

|  |

22. |

Physical

Activity and Fitness |

|

|

|

|

| 22-1. |  | No leisure-time physical activity |

| 22-2. |  | Moderate physical activity |

| 22-3. |  | Vigorous physical activity |

| 22-4. |  | Muscular strength and endurance |

| 22-5. |  | Flexibility |

|  |

23. |

Public Health

Infrastructure |

|  |

24. |

Respiratory

Diseases |

|

|

|

|

| 24-1. |  | Deaths from asthma |

| 24-2. |  | Hospitalizations for asthma |

| 24-3. |  | Hospital emergency department visits for asthma |

| 24-4. |  | Activity limitations |

| 24-5. |  | School or work days lost |

| 24-6. |  | Patient education |

| 24-7. |  | Appropriate asthma care |

| 24-8. |  | Surveillance systems |

| 24-9. |  | Activity limitations due to chronic lung and breathing problems |

| 24-10. |  | Deaths from COPD |

|  |

27. |

Tobacco Use |

|  |

28. |

Vision and Hearing |

(A listing of abbreviations and acronyms used in this

publication appears in Appendix H.)

Activity limitations: Problems in a person’s performance of everyday

functions such as communication, self-care, mobility, learning, and behavior.

Assistive devices and technology: Under the Assistive

Technology Act of 1998 (Public Law 105-394), “any

item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially,

modified, or customized, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional

capabilities of individuals with disabilities.”

Congregate care facilities: An out-of-home facility

that provides housing for people with disabilities in which rotating staff

members provide care—16 or

more beds when referring to adults and any number of beds when referring to

children and youth under age 21 years. Congregate care excludes foster care,

adoptive homes, residential schools, correctional facilities, and nursing facilities.30

Disability: The general term used to represent the

interactions between individuals with a health condition and barriers in their

environment.

Environmental factors: The policies, systems, social

contexts, and physical barriers or facilitators that affect a person’s participation in activities,

including work, school, leisure, and community events.

Health promotion: Efforts to create healthy

lifestyles and a healthy environment to prevent medical and other secondary

conditions, such as teaching people how to address their health care needs and

increasing opportunities to participate in usual life activities.

ICIDH-2: International Classification of

Functioning and Disability, the World Health Organization’s conceptual and coding framework

for describing a person’s

functioning and disability associated with his or her health condition.

People with disabilities: People identified as having

an activity limitation or who use assistance or who perceive themselves as

having a disability.

Permanency planning: A planning process undertaken by

public and private agencies on behalf of a child with developmental

disabilities and their families with the explicit goal of securing a permanent

living arrangement that enhances the child’s

growth and development.41

Secondary conditions:

Medical, social, emotional, mental, family, or community problems that a person

with a primary disabling condition likely experiences.

[1]

World Health Organization (WHO). International

Classification of Functioning and Disability (ICIDH-2): Beta-1 Draft for Field

Trials. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 1997, 11-21, 206-215, 221-225.

[2]

McNeil, J.M. Americans with disabilities 1994–95. Current

Populations Report P7061:3-6, August 1997.

[3]

National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research. Trends in Disability Prevalence and Their Causes:

Proceedings of the Fourth National Disability Statistics and Policy Forum, May

16, 1997, Washington, DC. San Francisco, CA: The Disability Statistics

Rehabilitation Research and Training Center, 1998.

[4]

Institute of Medicine. Enabling America: Assessing

the Role of Rehabilitation Science and Engineering. Washington, DC:

National Academy Press, 1997, 2.

[5]

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Healthy

People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives.

Pub. No. (PHS) 91-50213. Washington, DC: HHS, Public Health Service (PHS),

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP), 1991, 39-42.

[6]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health-related quality of

life and activity limitation—Eight states, 1995. Morbidity

and Mortality Weekly Report (47):134-140, 1998.

PubMed; PMID 9498296

[7]

Manton, K.; Corder, L.; and Stallard, E. Chronic

Disability Trends in Elderly in United States Populations 1982–1994.

Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, 1997, 2593-2598.

[8]

Zola, I. Disability statistics, what we count and what it tells us, a personal

and political analysis. Journal of Disability Policy

Studies 4(2):10-39, 1993.

[9]

Hahn, H. The political implications of disability definitions and data. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 4(2):42-52,

1993.

[10]

HHS. Healthy People 2000 Progress Review, People With

Disabilities. Washington, DC: HHS, PHS, ODPHP, 1997, 1-3.

[11]

Seekins, T.; White, G.; Ravesloot, C.; et al. Developing and evaluating

community-based health promotion programs for people with disabilities. In: Secondary Conditions Among People With Disabilities:

Current Research and Trends. Pacific Grove, CA: Brookes-Cole Publisher,

in press.

[12]

Lorig, K. A workplace health education program that reduces outpatient visits. Medical Care 9:1044-1054, 1995.

PubMed; PMID 4033235

[13]

Research and Training Center on Rural Rehabilitation. Cost Containment Through Disability Prevention: Preliminary

Results of a Health Promotion Workshop for People With Physical Disabilities.

Missoula, MT: University of Montana, the Center, 1996.

[14] Lorig, K.; Lubeck, D.; Kraines, R.; et

al. Outcomes of self-help education for patients with arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatism 28(6):680-685, 1985.

PubMed; PMID 4004977

[15]

National Osteoporosis Foundation. Physician Guide to

Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: the

Foundation, 1998.

[16]

Melnikova, N; Hough, J.; and Lollar, D. Osteoporosis among women with physical

disabilities: Risk factors and protective factors. Paper presented at 126th

Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association, Disability Forum

Special Interest Group in Washington, DC, November 17, 1998.

[17]

HHS. Healthy People in Healthy Communities: A Guide

for Community Leaders. Washington, DC: HHS, PHS, Office of Public Health

and Science (OPHS), ODPHP, 1998.

[18]

HHS. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Guide to

Clinical Preventive Services. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: HHS, OPHS, ODPHP,

1995, Chapter V.

[19]

HHS. Task Force on Community Preventive Services:

Guide to Community Preventive Services. Washington, DC: HHS, in press.

[20]

U.S. Public Health Service. Putting Prevention Into

Practice: Clinicians Handbook of Preventive Services. 2nd ed. McLean,

VA: International Medical Publishing, Inc., 1998, Chapter 36.

[21]

National Council on Disability. Reorienting

Disability Research: Letter to the United States President. Washington,

DC: the Council, 1998, 1-17.

[22]

Office on Disability and Health. 1999 Behavioral Risk

Factor Surveillance System Disability Module. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 1999.

[23]

Tuttle, D. Self Esteem and Adjusting With Blindness:

The Process of Responding to Life Demands. Springfield, IL: Charles C.

Thomas Publisher, 1984, 61, 145-158.

[24]

Sowers, J., and Powers, L. Enhancing the participation and independence of

students with severe and multiple disabilities in performing community

activities. Mental Retardation 33(4):209-220,

1995.

PubMed; PMID 7565143

[25]

Kaye, S. Is the status of people with disabilities improving? Disability Status Abstract (21):3-4, May 1998.

[26]

Novack, T., and Gage, R. Assessment of family functioning and social support.

In: Cushman, L., and Scherer, M., eds. Psychological

Assessment in Medical Rehabilitation. Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association, 1995, 286-297.

[27]

Patrick, D. Rethinking prevention for people with disabilities part 1: A

conceptual model for promoting health. American

Journal of Health Promotion 11(4):25-260, 1997.

PubMed; PMID 10172932

[28]

Swain, P. Helping disabled people: The users view. British

Medical Journal 306(6883):990-992, 1993.

PubMed; PMID 8490483

[29]

Braddock, D.; Hemp, R.; Parish, S.; et al. The State

of the States in Developmental Disabilities. 5th ed. Washington, DC:

American Association on Mental Retardation, 1998, 9-10.

[30]

Prouty, R., and Lakin, K. Residential Services for

Persons With Developmental Disabilities: Status and Trends Through 1997.

Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, Research Training Center on Community

Living, Institute on Community Integration, 1998, xii, 47, 53, 58, 60, 65-67,

76, 88, 101.

[31]

Kane, R. Expanding the home care concept: Blurring distinctions among home

care, institutional care and other long-term care facilities. Milbank Quarterly 73(2):161-186, 1995.

PubMed; PMID 7776944

[32]

Hardwick, S.; Pack, J.; Donohoe, E.; et al. Across

the States 1994: Profiles of Long-Term Care Systems. Washington, DC:

American Association of Retired Persons, Center on Elderly People Living Alone,

Public Policy Institute, 1994, 5-7.

[33]

Presidential Task Force on Employment of Adults with Disabilities. Recharting the Course: First Report. Washington, DC:

the Task Force, 1998.

[34] Stoddard, S.; Jans, L.; Ripple, J.; et

al. Chartbook on Work and Disabilities in the

United States, 1998. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education (DoE),

National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation, 1998.

[35]

DoE. To Assure the Free Appropriate Public Education

of All Children with Disabilities: Nineteenth Annual Report to Congress on the

Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Section 618.

Washington, DC: DoE, 1997.

[36]

Laplante, M.; Hendershot, G.; and Moss, A. Assistive technology devices and

home accessibility features: Prevalence, payment, need, and trends. In: Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics: No. 217.

Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1992.

[37]

National Council on Disability. Study on Financing of

Assistive Technology Devices and Services for Individuals With Disabilities.

Washington, DC: the Council, 1993.

[38]

National Council on Disability. Equality of

Opportunity: The Making of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Washington, DC: the Council, 1997, 9-21.

[39]

Craig Hospital and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

Craig Hospital Inventory of Environmental Factors. Short form (CHIEF SF). Colorado 1999 Behavioral Risk Surveillance System

Disability Study. Englewood, CO: Craig Hospital, Denver, CO, and

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Survey Research Unit.

[40]

National Alliance for Caregiving and the American Association of Retired

Persons. Family Caregiving in the U.S.: Findings From

a National Survey. Bethesda, MD: American Association of Retired

Persons, Washington, DC, 1997, 8.

[41]

Singer, G., and Irvin, L. Support for Caregiving

Families: Enabling Positive Adaptation to Disability. Baltimore, MD:

Paul H. Brooks Publishing Company, 1989, 44.

[42]

Pugliese, J.M.; Ingram, T.O.; and Edwards, G. Stability

of Employment Status of Caregivers Who Have a Child With a Disability.

Birmingham, AL: United Cerebral Palsy of Greater Birmingham, Inc., 1998.