Issues in Labor Statistics | Summary 10-05 | June 2010

PDF file of this Issue in Labor Statistics | Other Issues in Labor Statistics

Long-term unemployment experience of the jobless

by Randy Ilg

By the end of 2009, the jobless rate stood at 10.0 percent and the number of unemployed persons at 15.3 million. Among the unemployed, 4 in 10 (6.1 million) had been jobless for 27 weeks or more, by far the highest proportion of long-term unemployment on record, with data back to 1948. This brief report compares the incidence of long-term joblessness among different age groups during the current recession. To be classified as unemployed for more than half a year, individuals must persevere in their job search, and this persistence varies among age groups. For this reason, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) uses labor force flows to gain insight into whether the unemployed in some age groups are more likely than others to find jobs, continue to search for jobs, or leave the labor force altogether. Labor force flows can be used to calculate the probability of individuals moving between each of the labor force classifications—employment, unemployment, and not in the labor force—from one month to the next.

By the end of 2009, the jobless rate stood at 10.0 percent and the number of unemployed persons at 15.3 million. Among the unemployed, 4 in 10 (6.1 million) had been jobless for 27 weeks or more, by far the highest proportion of long-term unemployment on record, with data back to 1948. This brief report compares the incidence of long-term joblessness among different age groups during the current recession. To be classified as unemployed for more than half a year, individuals must persevere in their job search, and this persistence varies among age groups. For this reason, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) uses labor force flows to gain insight into whether the unemployed in some age groups are more likely than others to find jobs, continue to search for jobs, or leave the labor force altogether. Labor force flows can be used to calculate the probability of individuals moving between each of the labor force classifications—employment, unemployment, and not in the labor force—from one month to the next.

During the current recession, rising unemployment has led to record high levels of long-term joblessness. A relatively simple measure of a group’s exposure to long-term unemployment is its long-term jobless rate, or the proportion of the group’s labor force total that has been unemployed for 27 weeks or more.[1] As shown in table 1, the long-term unemployment rate for all persons increased from 0.8 percent in 2007 to a high of 2.9 percent in 2009. Moreover, upswings in the measure were pervasive across all age groups. While young workers had the higher nominal increase in their long-term unemployment rate, prime-age and older workers had a somewhat larger increase on a percent basis. (Unless otherwise noted, comparisons herein focus on annual average data for 2007, most of which occurred just prior to the onset of the recession in December of that year, and 2009, the most recent annual average data available.)[2]

Younger workers were overrepresented among the long-term jobless in 2009, making up 19.5 percent of all persons unemployed for 27 weeks or more, compared with 13.9 percent of the labor force. This is not unusual, because youths have made up a disproportionately larger share of the long-term jobless in every recession but one since 1976.

At first glance, it appears that younger workers in the current economic downturn have been hit particularly hard by long-term unemployment because of their high long-term unemployment rate and their disproportionate share of the long-term jobless. Once unemployed, however, younger workers actually have a relatively low probability of remaining jobless for a half year or more. As shown in table 1, only 23.3 percent of unemployed youths were jobless for 27 weeks or more in 2009, compared with 33.4 percent of prime-age workers and 39.4 percent of older workers. Furthermore, the share of long-term unemployed made up of youths declined between 2007 and 2009, while the share made up of older workers rose. Older workers also experienced an average duration spell of 29.5 weeks of unemployment, the longest among the groups.[3]

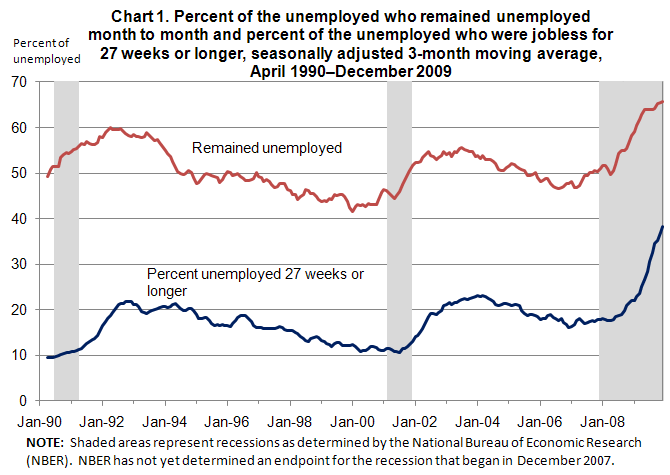

Analysis of labor force status flows can provide some insight into the apparent inconsistencies in the long-term unemployment experience among age groups. Flows capture movements between employment and unemployment as well as entry into and exit out of the labor force. For example, a person who is unemployed in one month may still be jobless the next month, or he or she might be employed or no longer participating in the labor market at all. Thus, labor force flows are a useful tool to assess whether unemployed individuals are more likely to remain unemployed, find a job, or leave the labor force. While the flow data do not indicate the length of time that individuals have been unemployed, there is a strong correlation between the share of the unemployed who have been jobless for 27 weeks or more and the share of unemployed who remain jobless from one month to the next. As chart 1 shows, these two series move in lockstep with each other through recessionary and expansionary periods alike.

As the current recession deepened and job loss intensified, there were significant changes in the flows out of unemployment.[4] Overall, the rate of successful job search (unemployed to employed) plummeted. (See table 2.) In 2009, only 17 percent of all the unemployed in one month found jobs by the next month, compared with about 28 percent of the unemployed in 2007. In 2009, 18 percent of workers ages 25 to 54 were successful in their job search. Younger workers were about as likely as prime-age workers to find work in 2009. Unemployed older workers were the least likely of all to find jobs, with only about 15 percent of jobseekers finding jobs each month in 2009, compared with about 22 percent in 2007.

Similarly, as the likelihood of successful job search declined for each age group during the recession, the probability of remaining unemployed rose sharply. These changes contributed to rising numbers of longterm unemployed. Declines in successful job search and longer periods of unemployment are expected outcomes from such a severe job market downturn. What is less predictable is the extent to which unemployed workers would persevere in their search for employment after failing for so long to find jobs.

As shown in table 2, unemployed prime-age workers and older workers became substantially less inclined to drop out of the labor force between 2007 and 2009.[5] This put upward pressure on both their overall unemployment rates and long-term unemployment rates. In contrast, the share of unemployed youths that left the labor force, which was always high, remained stable over the course of the recession, at about 30 percent.

Thus, as the recession lengthened and unemployment rose, the share of jobless workers ages 25 to 54 and those 55 years and over that remained unemployed from month to month increased, while the share that left the labor force or became employed declined. These changes all contributed to the overall rise in long-term unemployment among those age groups. The share of jobless younger workers that remained unemployed also increased, but they were still as likely to drop out of the labor force as they were before the onset of the recession. If they had been less inclined to leave the labor market, as were the other age groups, long-term joblessness among youth would have increased even more than it did.

This Issues paper was prepared by Randy Ilg, an economist in the Division of Labor Force Statistics, Office of Employment and Unemployment Statistics. E-mail: CPSinfo@bls.gov; Telephone: (202) 691-6378.

Information in this summary will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 691-5200. Federal Relay Service: 1-800-877-8339. This report is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission.

Notes

[1] The labor force is made up of the employed plus the unemployed—those who are actively looking for and are available for work.

[2] The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) determined that the most recent recession began in December 2007. NBER has not yet determined an endpoint for the recession.

[3] The average duration measure represents the length of time that unemployed individuals had been looking for work when surveyed; thus it refers to incomplete spells of joblessness rather than the duration of completed spells.

[4] Seasonally adjusted labor force status flows are not available by age; thus, data presented herein are annualized, not seasonally adjusted.

[5]Individuals leave the labor force for a variety of reasons, including retirement, discouragement over job prospects, school attendance, and family responsibility.