What I need to know about Liver Transplantation

On this page:

- What is liver transplantation?

- What does my liver do?

- What are the signs and symptoms of liver problems?

- What are the reasons for needing a liver transplant?

- How will I know whether I need a liver transplant?

- Can anyone with liver problems get a transplant?

- How long does it take to get a new liver?

- Where do the livers for transplants come from?

- What happens in the hospital?

- What is organ rejection?

- How is organ rejection prevented?

- Do anti-rejection medicines have any side effects?

- What are the signs of organ rejection?

- What other problems can damage my new liver?

- What if the liver transplant doesn’t work?

- How do I take care of my liver after I leave the hospital?

- Can I go back to my daily activities?

- Points to Remember

- Hope through Research

- Pronunciation Guide

- For More Information

- Acknowledgments

What is liver transplantation?

Liver transplantation is surgery to remove a diseased or injured liver and replace it with a healthy one from another person, called a donor. Many people have had liver transplants and now lead normal lives.

[Top]

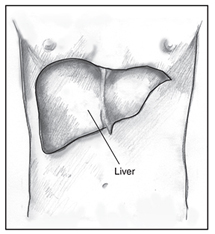

What does my liver do?

Your liver helps fight infections and cleans your blood. It also helps digest food and stores a form of sugar your body uses for energy. The liver is the largest organ in your body.

[Top]

What are the signs and symptoms of liver problems?

Some signs and symptoms of liver problems are

- yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes, a condition called jaundice*

- feeling tired or weak

- losing your appetite

- feeling sick to your stomach

- losing weight

- losing muscle

- itching

- bruising or bleeding easily

- bleeding in the stomach

- throwing up blood

- passing black stools

- having a swollen abdomen

- becoming forgetful or confused

You cannot live without a liver that works. If your liver stops working as it should, you may need a liver transplant.

Losing your appetite can be a sign of liver problems.

*See the Pronounciation Guide for tips on how to say the words in bold type.

[Top]

What are the reasons for needing a liver transplant?

In adults, the most common reason for needing a liver transplant is cirrhosis. Cirrhosis can be caused by many different types of diseases that destroy healthy liver cells and replace them with scar tissue.

Some causes of cirrhosis are

- long-term infection with the hepatitis C virus

- drinking too much alcohol over time

- autoimmune liver diseases

- long-term infection with the hepatitis B virus

- the buildup of fat in the liver

- hereditary liver diseases

Your body’s natural defense system, called the immune system, keeps you healthy by fighting against things that can make you sick, such as bacteria and viruses. Autoimmune liver diseases occur when your immune system doesn’t recognize the liver as a part of your body and attacks it. Hereditary diseases are passed from parents to children through genes.

In children, the most common reason for needing a liver transplant is biliary atresia. In biliary atresia, bile ducts are missing, damaged, or blocked. Bile ducts are tubes that carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder and small intestine. When bile ducts are blocked, bile backs up in the liver and causes cirrhosis.

Other reasons for needing a liver transplant include

- sudden liver failure, called acute liver failure, most often caused by taking too much acetaminophen (Tylenol)

- liver cancers that have not spread outside the liver

Liver transplants can help children and adults.

[Top]

How will I know whether I need a liver transplant?

Your doctor will decide whether you need to go to a liver transplant center to be evaluated by a liver transplant team. The team will include liver transplant surgeons; liver specialists, called hepatologists; nurses; social workers; and other health care professionals. The transplant team will examine you and run blood tests, x rays, and other tests to help decide whether you would benefit from a transplant.

The transplant team will also check to see if

- your heart, lungs, kidneys, and immune system are strong enough for surgery

- you are mentally and emotionally ready to have a transplant

- you have family members or friends who can care for you before and after the transplant

Even if you are approved for a transplant, you may choose not to have it. To help you decide, the transplant team will explain the

- patient selection process

- operation and recovery

- long-term demands of living with a liver transplant, such as taking medicines for the rest of your life

During your evaluation, and while waiting for a transplant, you should take care of your health. Your doctor will tell you what you can do to stay strong while you wait for a new liver.

[Top]

Can anyone with liver problems get a transplant?

Each transplant center has rules about who can have a liver transplant. You may not be able to have a transplant if you have

- cancer outside the liver

- serious heart or lung disease

- an alcohol or drug abuse problem

- a severe infection

- AIDS

- trouble following your doctor’s instructions

- no support system

[Top]

How long does it take to get a new liver?

If you need a transplant, your name will be placed on a national waiting list kept by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). Your blood type, body size, and how urgently you need a new liver all play a role in when you will receive a liver. Those with the most urgent need for a liver to prevent death are at the top of the list. Many people have to wait a long time to get a new liver.

Your doctor will tell you what you can do to stay

strong while you wait for a new liver.

For information about the national waiting list, please contact the UNOS. See the For More Information section for contact information.

[Top]

Where do the livers for transplants come from?

Most livers come from people who have just died. This type of donor is called a deceased donor. Sometimes a healthy living person will donate part of his or her liver to a patient, usually a family member. This type of donor is called a living donor. Both types of transplants usually have good results.

All donated livers and living donors are tested before transplant surgery. The testing makes sure the donor liver works as it should, matches your blood type, and is the right size, so it has the best chance of working in your body. Adults usually receive the entire liver from a deceased donor. Sometimes only a portion of a whole liver from a deceased donor is used to fit a smaller person. In some cases, a liver from a deceased donor is split into two parts. The smaller part may go to a child, and the larger part may go to an adult.

Health Insurance

You should check your health insurance policy to be sure it covers a liver transplant and prescription medicines. You will need many prescription medicines after the surgery and for the rest of your life.

[Top]

What happens in the hospital?

When a liver is available, you will need to get to the hospital quickly to be prepared for the surgery. If your new liver is from a living donor, both you and the donor will have surgery at the same time. If your new liver is from a deceased donor, your surgery will start when the new liver arrives at the hospital.

The surgery can take up to 12 hours. The surgeon will remove your liver and then replace it with the donated liver.

After Surgery

You will stay in the hospital about 1 to 2 weeks to be sure your new liver is working. You’ll take medicines to prevent infections and rejection of your new liver. Your doctor will check for bleeding, infections, and liver rejection. During this time, you will learn how to take care of yourself after you go home and about the medicines you’ll need to take to protect your new liver.

After surgery, you will learn how to take care of yourself when you go home.

[Top]

What is organ rejection?

Rejection occurs when your immune system attacks the new liver. After a transplant, it is common for your immune system to try to destroy the new liver.

[Top]

How is organ rejection prevented?

To keep your body from rejecting the new liver, you will take anti-rejection medicines, also called immunosuppressive medicines. You will need to take anti-rejection medicines for the rest of your life.

[Top]

Do anti-rejection medicines have any side effects?

Anti-rejection medicines can have many serious side effects. You can get infections more easily because these medicines weaken your immune system. Other possible side effects include

- weight gain

- high blood pressure

- high blood cholesterol

- diabetes

- brittle bones

- kidney damage

- skin cancer

Your doctor and the transplant team will watch for and treat any side effects.

[Top]

What are the signs of organ rejection?

If your body rejects your new liver, you might feel tired, lose your appetite, or feel sick to your stomach. Other signs might include having

- a fever

- pain around the liver

- jaundice

- dark-colored urine

- light-colored stools

But rejection doesn’t always make you feel ill. Doctors will check your blood for signs of rejection. A liver biopsy is usually needed to tell whether your body is rejecting the new liver. For a biopsy, the doctor takes a small piece of the liver to view with a microscope.

Blood tests can help show if the new liver is being rejected.

[Top]

What other problems can damage my new liver?

Recurrence of the disease that caused the need for a transplant can damage a new liver. For example, the hepatitis C virus may return and damage the new liver in a patient who had hepatitis C before the transplant.

Other possible problems include

- blockage of the blood vessels going into or out of the liver

- damage to the bile ducts

[Top]

What if the liver transplant doesn’t work?

Liver transplants usually work. About 80 to 85 percent of transplanted livers are still working after 1 year. If the new liver does not work or if your body rejects it, your doctor and the transplant team will decide whether another transplant is possible.

[Top]

How do I take care of my liver after I leave the hospital?

After you leave the hospital, you will see your doctor often to be sure your new liver is working well. You will have regular blood tests to check that your new liver is not being damaged by rejection, infections, or problems with blood vessels or bile ducts.

To help care for your liver, you will need to

- avoid people who are ill and report any illnesses you have to your doctor

- eat a healthy diet, exercise, not smoke cigarettes, and not drink alcohol

- take prescribed medicines as directed

- ask your doctor before taking any other medicines, including ones you can buy without a prescription

- follow your doctor’s instructions about how to take care of your new liver

- have blood tests and other tests as directed by your doctor

- use sunblock to prevent skin cancer and have cancer screening tests recommended by your doctor

Eating a healthy diet and taking medicines are part of taking care of your new liver.

[Top]

Can I go back to my daily activities?

After a successful liver transplant, most people can go back to their normal daily activities, and many return to work. Getting your strength back may take months, though, especially if you were very sick before the transplant. Your doctor will let you know how long your recovery period will be. Social workers and support groups can help you adjust to life with a new liver.

Work. After recovery, most people are able to return to work. Your doctor will let you know when you can go back to work.

Diet. Most people can go back to eating as they did before the transplant. Some medicines prescribed after your transplant may cause you to gain weight, and others may cause diabetes or raise your cholesterol. Eating a balanced, low-fat diet can help you stay healthy.

Exercise. Most people can be physically active after a liver transplant.

Sex. Most people can have a normal sex life after a liver transplant. For women, avoiding pregnancy in the first year after a transplant is recommended. Talk with your transplant team about when it’s okay to have sex again or get pregnant after your transplant.

If you have any questions, check with your doctor.

[Top]

Points to Remember

- Liver transplantation is surgery to remove a diseased or injured liver and replace it with a healthy one from another person, called a donor.

- If your liver stops working as it should, you may need a liver transplant.

- In adults, the most common reason for needing a liver transplant is cirrhosis. Cirrhosis can be caused by many different types of diseases that destroy healthy liver cells and replace them with scar tissue. Some causes of cirrhosis are long-term infection with the hepatitis C virus, drinking too much alcohol over time, and autoimmune and other liver diseases.

- In children, the most common reason for needing a liver transplant is biliary atresia. In biliary atresia, bile ducts in the liver are missing, damaged, or blocked. As a result, bile backs up in the liver and causes cirrhosis.

- Your doctor will decide whether you need to go to a liver transplant center to be evaluated by a liver transplant team. The transplant team will examine you and run blood tests, x rays, and other tests to help decide whether you would benefit from a transplant.

- People with the most urgent need for a new liver to prevent death are at the top of the national waiting list. Many people have to wait a long time to get a new liver.

- Most livers come from people who have just died. This type of donor is called a deceased donor. Some transplants involve living donors who donate part of their liver, usually to a family member.

- Liver transplant surgery can take up to 12 hours. You will stay in the hospital about 1 to 2 weeks after surgery.

- Problems after surgery may include bleeding, infections, and rejection of the new liver.

- Rejection occurs when your immune system attacks the new liver. After a transplant, it is common for your immune system to try to destroy the new liver.

- After a liver transplant, you must take anti-rejection medicines for the rest of your life to keep your body from rejecting your new liver.

- Liver transplants usually work. Most people are able to return to work and other normal activities after a transplant.

[Top]

Hope through Research

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) conducts and supports research on liver diseases and liver transplantation. Researchers are working to find better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat liver diseases and to improve liver transplantation outcomes.

Participants in clinical trials can play a more active role in their own health care, gain access to new research treatments before they are widely available, and help others by contributing to medical research. For information about current studies, visit www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

[Top]

Pronunciation Guide

acetaminophen (uh-SEE-tuh-MIH-noh-fen)

autoimmune (AW-toh-ih-MYOON)

biliary atresia (BIL-ee-air-ee) (uh-TREE-zee-uh)

biopsy (BY-op-see)

cirrhosis (sur-ROH-siss)

hepatologists (hep-uh-TAW-loh-jists)

hereditary (huh-RED-ih-TAIR-ee)

immunosuppressive (IM-yoo-noh-soo-PRESS-iv)

jaundice (JAWN-diss)

[Top]

For More Information

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

1001 North Fairfax, Suite 400

Alexandria, VA 22314

Phone: 703–299–9766

Fax: 703–299–9622

Email: aasld@aasld.org

Internet: www.aasld.org ![]()

American Liver Foundation

75 Maiden Lane, Suite 603

New York, NY 10038–4810

Phone: 1–800–GO–LIVER (1–800–465–4837) or 212–668–1000

Fax: 212–483–8179

Internet: www.liverfoundation.org ![]()

Hepatitis Foundation International

504 Blick Drive

Silver Spring, MD 20904

Phone: 1–800–891–0707 or 301–622–4200

Fax: 301–622–4702

Email: hfi@comcast.net

Internet: www.hepfi.org ![]()

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

Internet: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov

United Network for Organ Sharing

P.O. Box 2484

Richmond, VA 23218

Phone: 1–888–894–6361 or 804–782–4800

Fax: 804–782–4817

Internet: www.unos.org ![]()

This publication may contain information about medications. When prepared, this publication included the most current information available. For updates or for questions about any medications, contact the U.S. Food and Drug Administration toll-free at 1–888–INFO–FDA (1–888–463–6332) or visit www.fda.gov. Consult your doctor for more information.

[Top]

Acknowledgments

Publications produced by the Clearinghouse are carefully reviewed by both NIDDK scientists and outside experts. The National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse would like to thank the following individuals for assisting with the scientific and editorial review of either the original version or the 2010 version of this publication, or both:

Ann Harper

United Network for Organ Sharing

Michael R. Lucey, M.D.

University of Wisconsin–Madison

John M. Vierling, M.D.

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston

Jay H. Hoofnagle, M.D.

NIDDK

Thank you also to Jane Gerber, L.C.S.W.-C., University of Maryland Medical System, and Ann Payne, M.S.W., Inova Fairfax Hospital, for facilitating field-testing of the original version of this publication.

The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. Trade, proprietary, or company names appearing in this document are used only because they are considered necessary in the context of the information provided. If a product is not mentioned, the omission does not mean or imply that the product is unsatisfactory.

National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

2 Information Way

Bethesda, MD 20892–3570

Phone: 1–800–891–5389

TTY: 1–866–569–1162

Fax: 703–738–4929

Email: nddic@info.niddk.nih.gov

Internet: www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

The National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NDDIC) is a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The NIDDK is part of the National Institutes of Health of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Established in 1980, the Clearinghouse provides information about digestive diseases to people with digestive disorders and to their families, health care professionals, and the public. The NDDIC answers inquiries, develops and distributes publications, and works closely with professional and patient organizations and Government agencies to coordinate resources about digestive diseases.

Publications produced by the Clearinghouse are carefully reviewed by both NIDDK scientists and outside experts.

This publication is not copyrighted. The Clearinghouse encourages users of this publication to duplicate and distribute as many copies as desired.

NIH Publication No. 10–4941

June 2010

[Top]

Page last updated May 10, 2012