Featured Article

New Therapies Offer Much-Needed Options for Patients with Melanoma

More than 25,000 physicians, researchers, and health care professionals from more than 100 countries attended the 2011 American Society for Clinical Oncology annual meeting. (Image courtesy of ASCO)

More than 25,000 physicians, researchers, and health care professionals from more than 100 countries attended the 2011 American Society for Clinical Oncology annual meeting. (Image courtesy of ASCO)The much-anticipated findings from two phase III clinical trials of new therapies for patients with metastatic melanoma did not disappoint those in attendance at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting in Chicago last week.

The trials confirmed that the molecularly targeted agent vemurafenib and the immunotherapy agent ipilimumab (Yervoy) offer valuable new options for a disease in which effective treatments have been lacking.

Promising data on melanoma were also seen in a small clinical trial that identified a potential approach to preventing a key side effect of agents with the same molecular target as vemurafenib, a mutated form of the BRAF gene. (See the box at the bottom of the page.) And other lab-based studies identified potential biomarkers that may predict which tumors are more likely to respond to vemurafenib and ipilimumab.

After decades of almost no progress, this new research represents a welcome and long-awaited change, remarked Dr. Lynn Schuchter leader of the melanoma program at the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center.

"I think it's a time for celebration for our patients," she said, "for hope."

Vemurafenib: Early Phase III Results Again Show Strong, Rapid Responses

The vemurafenib trial, called BRIM3, enrolled 675 patients with newly diagnosed, inoperable metastatic melanoma, all of whom had tumors with the BRAF mutation. The patients were randomly assigned to receive either vemurafenib or the chemotherapy drug dacarbazine, the standard treatment for most patients with advanced disease. At the first planned interim analysis of trial data at 3 months, there were already statistically significant reductions in the risk of death (63 percent) and disease progression (74 percent) in patients being treated with vemurafenib compared with patients receiving dacarbazine.

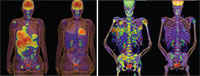

Before and after images of two patients treated for 2 weeks with vemurafenib (Images courtesy of Plexxikon) [Enlarge]

Before and after images of two patients treated for 2 weeks with vemurafenib (Images courtesy of Plexxikon) [Enlarge]Almost half of the patients taking vemurafenib had substantial tumor regressions, compared with fewer than 6 percent of the patients being treated with dacarbazine. Because of the dramatic effect on tumors, patients receiving dacarbazine were switched to vemurafenib, which may complicate the trial's overall survival analysis, several researchers noted.

At the time of the first interim analysis, "we had just finished accrual to the trial," explained the trial's lead investigator, Dr. Paul Chapman of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. "So this is unprecedented to report a trial this early…and yet [the survival] curves separated very early."

However, the trial hasn't gone on long enough to calculate a median overall survival, he noted.

The tumor response rate, although strong, was substantially less than what had been seen in the phase I and II trials of vemurafenib. Even though patients who respond to the treatment typically do so within 2 months of beginning treatment, that is not always the case, Dr. Chapman noted. And given the short follow up, he believes the response rate "will creep up."

The results also confirm that most tumor responses peak after approximately 6 months and that the disease will return. So a priority will be identifying therapies that can help overcome tumor resistance, he said.

Serious toxicities occurred in fewer than 10 percent of patients on vemurafenib, and common side effects of the drug included joint pain; sun sensitivity; and forms of nonmelanoma skin cancer, primarily squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which occurred in 18 percent of patients. SCC lesions can easily be excised by dermatologists, Dr. Chapman explained, and there have been no cases of metastatic SCC in any of the vemurafenib trials.

Nevertheless, nearly 40 percent of patients taking vemurafenib in the phase III trial had to stop treatment temporarily or have their dose reduced because of side effects.

Ipilimumab: A Subset of Patients Have Prolonged Responses

Results from the ipilimumab trial were far more mature than those from the vemurafenib trial. Five hundred and two patients with metastatic melanoma were randomly assigned to receive the immunotherapy in combination with dacarbazine or dacarbazine alone. Median overall survival improved by just 2 months: 11.2 months versus 9.1 months.

But those figures don't tell the whole story, said the trial's lead investigator, Dr. Jedd Wolchok, also of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. He pointed to the 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rates, which were all superior in patients who received ipilimumab. At 3 years, approximately 21 percent of patients were still alive in the ipilimumab arm compared with 12 percent in the chemotherapy-only arm.

There was also a 24 percent improvement in progression-free survival in the ipilimumab group, but no statistically significant difference in tumor shrinkage was found between the groups. The length of time for which patients maintained a tumor response was 19.3 months in the ipilimumab arm and 8.1 months in the dacarbazine arm. The greater response duration and survival at 3 years is "consistent with an immunotherapy," Dr. Wolchok said, because immunotherapies are more likely to keep tumors in check rather than produce significant tumor shrinkage.

High-grade adverse events occurred in nearly twice as many patients in the ipilimumab arm (56 percent) as the dacarbazine alone arm (27 percent). Although fewer patients receiving ipilimumab had high-grade diarrhea and colitis (swelling of the large intestine) than in previous trials, Dr. Wolchok explained, liver toxicity was substantially more frequent than previously seen, which he said was likely due to the combination with dacarbazine.

Which Treatment When?

Until the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ipilimumab in March, there were essentially two options for treating advanced melanoma: dacarbazine, which in most patients produces at most modest improvements in survival or symptomatic benefit, and interleukin-2, a highly toxic therapy that induces long-term remissions in only a small percentage of patients.

Roche and Plexxikon, the companies that co-developed vemurafenib, submitted an application for approval to the FDA last month and are expecting a decision some time this year. So, although both ipilimumab and vemurafenib will be options for patients with metastatic disease, a key clinical question remains: Which therapy should be used first in patients whose tumors have a BRAF mutation?

Because vemurafenib can lead to such rapid tumor regression, many researchers at the meeting suggested that vemurafenib would typically be the preferred first-line option for these patients.

During the meeting's plenary session, Dr. Kim A. Margolin of the University of Washington laid out a potential pattern of use for these patients. "Vemurafenib is appropriate for patients who have symptoms and need to respond fast," she said. "For those with limited tumor burden, limited symptoms, and whose long-term goal is durable benefit and who are not in urgent need of the physical and emotional relief associated with quick tumor regression, ipilimumab may well be the preferred choice."

Because of the serious liver side effects attributed to dacarbazine in the trial, however, she advised that ipilimumab be used alone.

Dr. Schuchter was quick to respond with how she will handle such patients. "I'll put them on a trial," she said. With studies rapidly identifying mechanisms of tumor resistance and potentially effective combinations of therapies, she continued, "we can further characterize patient tumors" by their different genetic abnormalities "and direct them to [trials testing] the right targeted therapies."

A clinical trial "is clearly the top priority," agreed Dr. Sekwon Jang, a medical oncologist at Washington Hospital Center who primarily treats melanoma patients. "We're going to have many more clinical trial options for patients," he said.

On the day before the ASCO meeting began, in fact, Roche and Bristol-Myers Squibb, the manufacturers of vemurafenib and ipilimumab, announced that they had entered into a collaborative agreement to conduct clinical trials testing the agents in combination.

If a patient cannot be enrolled in a clinical trial for some reason, Dr. Schuchter said, vemurafenib would likely be her first-line therapy of choice for most patients with BRAF mutations.

During an education session on melanoma therapy, Dr. Antoni Ribas of UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, who has been involved in studies of both agents, said he hoped that ipilimumab's less robust response rate compared with that of vemurafenib will not deter oncologists from using it. "It's unquestionable that ipilimumab has a positive impact on overall survival," he said.

Based on the clinical trial data, he continued, it's clear that a modest proportion of patients will have long, objective responses "and are probably cured."

Treating Melanoma: One Drug is Good, Two May Be Safer

Treating patients with advanced melanoma whose tumors have BRAF mutations with a BRAF inhibitor plus another targeted therapy appears to be at least as effective as using the BRAF inhibitor alone, and the combined therapy substantially reduces some of the side effects of each agent used alone, researchers reported at the ASCO annual meeting.

The findings come from a phase I clinical trial in which patients systematically received escalating doses of the experimental BRAF-targeted agent, GSK436, and a different experimental agent, GSK212, that targets a protein called MEK, which is in the same molecular signaling pathway as BRAF.

In earlier phase I trials, both drugs produced strong tumor responses in patients with advanced melanoma with BRAF mutations, but both had toxicities, including the development of squamous cell carcinomas in patients treated with GSK436 and an acne-like rash in patients treated with GSK212.

Among the 109 patients in the trial who have received both drugs together, only one developed a squamous cell carcinoma and the incidence of skin rashes was substantially reduced, reported Dr. Jeffrey Infante of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, TN. Only rarely did the dose of the drugs have to be reduced because of side effects, he added.

Of the 71 patients in the trial who had not yet been treated with a BRAF inhibitor, Dr. Infante said, between 55 and 77 percent had stable disease or some tumor shrinkage—including five patients who had complete responses—after receiving both drugs simultaneously, depending on the dose of the drugs used.

"The addition of a MEK inhibitor is clearly one of the logical next steps to improve upon the efficacy of single-agent BRAF inhibitors," he said.