For more information, visit http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/pda/

What Is Patent Ductus Arteriosus?

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a heart problem that affects some babies soon after birth. In PDA, abnormal blood flow occurs between two of the major arteries connected to the heart. These arteries are the aorta and the pulmonary (PULL-mun-ary) artery.

Before birth, these arteries are connected by a blood vessel called the ductus arteriosus. This blood vessel is a vital part of fetal blood circulation.

Within minutes or up to a few days after birth, the ductus arteriosus closes. This change is normal in newborns.

In some babies, however, the ductus arteriosus remains open (patent). The opening allows oxygen-rich blood from the aorta to mix with oxygen-poor blood from the pulmonary artery. This can strain the heart and increase blood pressure in the lung arteries.

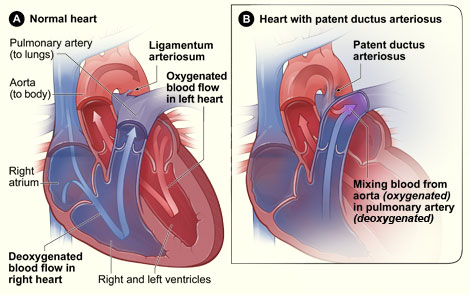

Normal Heart and Heart With Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Figure A shows a cross-section of a normal heart. The arrows show the direction of blood flow through the heart. Figure B shows a heart with patent ductus arteriosus. The defect connects the aorta and the pulmonary artery. This allows oxygen-rich blood from the aorta to mix with oxygen-poor blood in the pulmonary artery.

Go to the "How the Heart Works" section of this article for more details about how a normal heart works compared with a heart that has PDA.

Overview

PDA is a type of congenital (kon-JEN-ih-tal) heart defect. A congenital heart defect is any type of heart problem that's present at birth.

If your baby has a PDA but an otherwise normal heart, the PDA may shrink and go away. However, some children need treatment to close their PDAs.

Some children who have PDAs are given medicine to keep the ductus arteriosus open. For example, this may be done if a child is born with another heart defect that decreases blood flow to the lungs or the rest of the body.

Keeping the PDA open helps maintain blood flow and oxygen levels until doctors can do surgery to correct the other heart defect.

Outlook

PDA is a fairly common congenital heart defect in the United States. Although the condition can affect full-term infants, it's more common in premature infants.

On average, PDA occurs in about 8 out of every 1,000 premature babies, compared with 2 out of every 1,000 full-term babies. Premature babies also are more vulnerable to the effects of PDA.

PDA is twice as common in girls as it is in boys.

Doctors treat the condition with medicines, catheter-based procedures, and surgery. Most children who have PDAs live healthy, normal lives after treatment.

How the Heart Works

To understand patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), it helps to know how a normal heart works. Your child's heart is a muscle about the size of his or her fist. The heart works like a pump and beats 100,000 times a day.

The heart has two sides, separated by an inner wall called the septum. The right side of the heart pumps blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen. The left side of the heart receives the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and pumps it to the body.

The heart has four chambers and four valves and is connected to various blood vessels. Veins are blood vessels that carry blood from the body to the heart. Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart to the body.

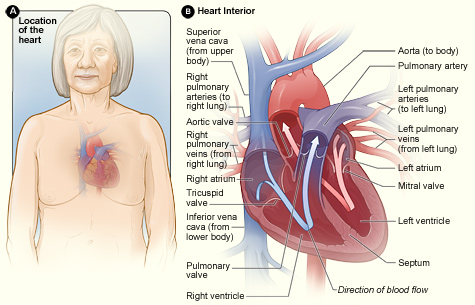

A Healthy Heart Cross-Section

Figure A shows the location of the heart in the body. Figure B shows a cross-section of a healthy heart and its inside structures. The blue arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-poor blood flows through the heart to the lungs. The red arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-rich blood flows from the lungs into the heart and then out to the body.

Heart Chambers

The heart has four chambers or "rooms."

- The atria (AY-tree-uh) are the two upper chambers that collect blood as it flows into the heart.

- The ventricles (VEN-trih-kuhls) are the two lower chambers that pump blood out of the heart to the lungs or other parts of the body.

Heart Valves

Four valves control the flow of blood from the atria to the ventricles and from the ventricles into the two large arteries connected to the heart.

- The tricuspid (tri-CUSS-pid) valve is in the right side of the heart, between the right atrium and the right ventricle.

- The pulmonary (PULL-mun-ary) valve is in the right side of the heart, between the right ventricle and the entrance to the pulmonary artery. This artery carries blood from the heart to the lungs.

- The mitral (MI-trul) valve is in the left side of the heart, between the left atrium and the left ventricle.

- The aortic (ay-OR-tik) valve is in the left side of the heart, between the left ventricle and the entrance to the aorta. This artery carries blood from the heart to the body.

Valves are like doors that open and close. They open to allow blood to flow through to the next chamber or to one of the arteries. Then they shut to keep blood from flowing backward.

When the heart's valves open and close, they make a "lub-DUB" sound that a doctor can hear using a stethoscope.

- The first sound—the "lub"—is made by the mitral and tricuspid valves closing at the beginning of systole (SIS-toe-lee). Systole is when the ventricles contract, or squeeze, and pump blood out of the heart.

- The second sound—the "DUB"—is made by the aortic and pulmonary valves closing at the beginning of diastole (di-AS-toe-lee). Diastole is when the ventricles relax and fill with blood pumped into them by the atria.

Arteries

The arteries are major blood vessels connected to your heart.

- The pulmonary artery carries blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs to pick up a fresh supply of oxygen.

- The aorta is the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood from the left side of the heart to the body.

- The coronary arteries are the other important arteries attached to the heart. They carry oxygen-rich blood from the aorta to the heart muscle, which must have its own blood supply to function.

Veins

The veins also are major blood vessels connected to your heart.

- The pulmonary veins carry oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to the left side of the heart so it can be pumped to the body.

- The superior and inferior vena cavae are large veins that carry oxygen-poor blood from the body back to the heart.

For more information about how a healthy heart works, go to the Health Topics How the Heart Works article. The article contains animations that show how your heart pumps blood and how your heart's electrical system works.

The Heart With Patent Ductus Arteriosus

The ductus arteriosus is a blood vessel that connects the aorta and pulmonary artery in unborn babies. This vessel allows blood to be pumped from the right side of the heart into the aorta, without stopping at the lungs for oxygen.

While a baby is in the womb, only a small amount of his or her blood needs to go to the lungs. This is because the baby gets oxygen from the mother's bloodstream.

After birth, the baby no longer is connected to the mother's bloodstream. Thus, the baby's blood must travel to his or her own lungs to get oxygen. As the baby begins to breathe on his or her own, the pulmonary artery opens to allow blood into the lungs. Normally, the ductus arteriosus closes because the infant no longer needs it.

Once the ductus arteriosus closes, blood leaving the right side of the heart no longer goes into the aorta. Instead, the blood travels through the pulmonary artery to the lungs. There, the blood picks up oxygen. The oxygen-rich blood returns to the left side of the heart and is pumped to the rest of the body.

Sometimes the ductus arteriosus remains open (patent) after birth. A PDA allows blood to flow from the aorta into the pulmonary artery and to the lungs. The extra blood flowing into the lungs strains the heart. It also increases blood pressure in the lung's arteries.

Effects of Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Full-term infants. A small PDA might not cause any problems, but a large PDA likely will cause problems. The larger the PDA, the greater the amount of extra blood that passes through the lungs.

A large PDA that remains open for an extended time can cause the heart to enlarge, forcing it to work harder. Also, fluid can build up in the lungs.

A PDA can slightly increase the risk of infective endocarditis (IE). IE is an infection of the inner lining of the heart chambers and valves.

In PDA, increased blood flow can irritate the lining of the pulmonary artery, where the ductus arteriosus connects. This irritation makes it easier for bacteria in the bloodstream to collect and grow, which can lead to IE.

Premature infants. PDA can be more serious in premature infants than in full-term infants. Premature babies are more likely to have lung damage from the extra blood flowing from the PDA into the lungs. These infants may need to be put on ventilators. Ventilators are machines that support breathing.

Increased blood flow through the lungs also can reduce blood flow to the rest of the body. This can damage other organs, especially the intestines and kidneys.

What Causes Patent Ductus Arteriosus?

If your child has patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), you may think you did something wrong during your pregnancy to cause the problem. However, the cause of patent ductus arteriosus isn't known.

Genetics may play a role in causing the condition. A defect in one or more genes might prevent the ductus arteriosus from closing after birth.

Who Is at Risk for Patent Ductus Arteriosus?

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a fairly common congenital heart defect in the United States. Although the condition can affect full-term infants, it's more common in premature infants.

On average, PDA occurs in about 8 out of every 1,000 premature babies, compared with 2 out of every 1,000 full-term babies.

PDA also is more common in:

- Infants who have genetic conditions, such as Down syndrome

- Infants whose mothers had German measles (rubella) during pregnancy

PDA is twice as common in girls as it is in boys.

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Patent Ductus Arteriosus?

A heart murmur may be the only sign that a baby has patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). A heart murmur is an extra or unusual sound heard during the heartbeat. Heart murmurs also have other causes besides PDA, and most murmurs are harmless.

Some infants may have signs or symptoms of volume overload on the heart and excess blood flow in the lungs. These signs and symptoms may include:

- Fast breathing, working hard to breathe, and shortness of breath. Premature infants may need extra oxygen or a ventilator to help them breathe.

- Poor feeding and poor weight gain.

- Tiring easily.

- Sweating with exertion, such as while feeding.

How Is Patent Ductus Arteriosus Diagnosed?

In full-term infants, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) usually is first suspected if a heart murmur is heard during a routine checkup.

A heart murmur is an extra or unusual sound heard during the heartbeat. Heart murmurs have other causes besides PDA, and most murmurs are harmless.

If a PDA is large, an infant also may have symptoms of volume overload and increased blood flow to the lungs. If a PDA is small, it may not be diagnosed until later in childhood.

If your child's doctor thinks your child has PDA, he or she may refer you to a pediatric cardiologist. This is a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating heart problems in children.

Premature babies who have PDA may not have the same signs and symptoms as full-term babies, such as heart murmurs. Doctors may suspect PDA in premature babies who have breathing problems soon after birth. Tests can help confirm a diagnosis.

Diagnostic Tests

Echocardiography

Echocardiography (echo) is a painless test that uses sound waves to create a moving picture of your baby's heart. The sound waves (called ultrasound) bounce off the structures of the heart. A computer converts the sound waves into pictures on a screen.

The test allows the doctor to clearly see any problems with the way the heart is formed or the way it's working. Echo is an important test for both diagnosing a heart defect and following the problem over time.

Echo can show the size of a PDA and how the heart is responding to the defect. When medical treatments are used to try to close a PDA, echo can show how well the treatments are working.

EKG (Electrocardiogram)

An EKG is a simple, painless test that records the heart's electrical activity. For babies who have PDA, an EKG can show whether the heart is enlarged. The test also can show other subtle changes that may suggest the presence of a PDA.

How Is Patent Ductus Arteriosus Treated?

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is treated with medicines, catheter-based procedures, and surgery. The goal of treatment is to close the PDA. Closure will help prevent complications and reverse the effects of increased blood volume.

Small PDAs often close without treatment. For full-term infants, treatment is needed if the PDA is large or causing health problems. For premature infants, treatment is needed if the PDA is causing breathing problems or heart problems.

Talk with your child's doctor about treatment options and how your family prefers to handle treatment decisions.

Medicines

Your child's doctor may prescribe medicines to help close your child's PDA.

Indomethacin (in-doh-METH-ah-sin) is a medicine that helps close PDAs in premature infants. This medicine triggers the PDA to constrict or tighten, which closes the opening. Indomethacin usually doesn't work in full-term infants.

Ibuprofen also is used to close PDAs in premature infants. This medicine is similar to indomethacin.

Catheter-Based Procedures

Catheters are thin, flexible tubes that doctors use as part of a procedure called cardiac catheterization (KATH-eh-ter-ih-ZA-shun). Catheter-based procedures often are used to close PDAs in infants or children who are large enough to have the procedure.

Your child's doctor may refer to the procedure as "transcatheter device closure." The procedure sometimes is used for small PDAs to prevent the risk of infective endocarditis (IE). IE is an infection of the inner lining of the heart chambers and valves.

Your child will be given medicine to help him or her relax or sleep during the procedure. The doctor will insert a catheter in a large blood vessel in the groin (upper thigh). He or she will then guide the catheter to your child's heart.

A small metal coil or other blocking device is passed through the catheter and placed in the PDA. This device blocks blood flow through the vessel.

Catheter-based procedures don't require the child's chest to be opened. They also allow the child to recover quickly.

These procedures often are done on an outpatient basis. You'll most likely be able to take your child home the same day the procedure is done.

Complications from catheter-based procedures are rare and short term. They can include bleeding, infection, and movement of the blocking device from where it was placed.

Surgery

Surgery to correct a PDA may be done if:

- A premature or full-term infant has health problems due to a PDA and is too small to have a catheter-based procedure

- A catheter-based procedure doesn't successfully close the PDA

- Surgery is planned for treatment of related congenital heart defects

Often, surgery isn't done until after 6 months of age in infants who don't have health problems from their PDAs. Doctors sometimes do surgery on small PDAs to prevent the risk of IE.

For the surgery, your child will be given medicine so that he or she will sleep and not feel any pain. The surgeon will make a small incision (cut) between your child's ribs to reach the PDA. He or she will close the PDA using stitches or clips.

Complications from surgery are rare and usually short term. They can include hoarseness, a paralyzed diaphragm (the muscle below the lungs), infection, bleeding, or fluid buildup around the lungs.

After Surgery

After surgery, your child will spend a few days in the hospital. He or she will be given medicine to reduce pain and anxiety. Most children go home 2 days after surgery. Premature infants usually have to stay in the hospital longer because of their other health issues.

The doctors and nurses at the hospital will teach you how to care for your child at home. They will talk to you about:

- Limits on activity for your child while he or she recovers

- Followup appointments with your child's doctors

- How to give your child medicines at home, if needed

When your child goes home after surgery, you can expect that he or she will feel fairly comfortable. However, you child may have some short-term pain.

Your child should begin to eat better and gain weight quickly. Within a few weeks, he or she should fully recover and be able to take part in normal activities.

Long-term complications from surgery are rare. However, they can include narrowing of the aorta, incomplete closure of the PDA, and reopening of the PDA.

Living With Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Most children who have PDAs live healthy, normal lives after treatment. Full-term infants will likely have normal activity levels, appetite, and growth after PDA treatment, unless they had other congenital heart defects.

For premature infants, the outlook after PDA treatment depends on other factors, such as:

- How early the child was born

- Whether the child has other illnesses or conditions, such as other congenital heart defects

Ongoing Care

Children who have PDAs are at slightly increased risk for infective endocarditis (IE). IE is an infection of the inner lining of the heart chambers and valves.

Your child's doctor will tell you whether your child needs antibiotics before certain medical procedures to help prevent IE. According to the most recent American Heart Association guidelines, most children who have PDAs don't need antibiotics.

Clinical Trials

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) is strongly committed to supporting research aimed at preventing and treating heart, lung, and blood diseases and conditions and sleep disorders.

NHLBI-supported research has led to many advances in medical knowledge and care. For example, this research has uncovered some of the causes of heart diseases and conditions, as well as ways to prevent or treat them.

Many more questions remain about heart diseases and conditions, including patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and other congenital heart defects. The NHLBI continues to support research aimed at learning more about these conditions. For example, the NHLBI currently sponsors two research groups that study congenital heart disease.

The Pediatric Heart Network conducts clinical research to improve outcomes and quality of life for children who have congenital heart disease and other pediatric heart diseases.

The Pediatric Cardiac Genomic Consortium (part of the NHLBI's Bench to Bassinet Program) conducts clinical research to find the genetic causes of congenital heart disease. This group's research also aims to pinpoint the genetic factors that affect clinical outcomes in people who have congenital heart disease.

Much of this research depends on the willingness of volunteers to take part in clinical trials. Clinical trials test new ways to prevent, diagnose, or treat various diseases and conditions.

For example, new treatments for a disease or condition (such as medicines, medical devices, surgeries, or procedures) are tested in volunteers who have the illness. Testing shows whether a treatment is safe and effective in humans before it is made available for widespread use.

By taking part in a clinical trial, your child can gain access to new treatments before they're widely available. Your child also will have the support of a team of health care providers, who will likely monitor his or her health closely. Even if your child doesn't directly benefit from the results of a clinical trial, the information gathered can help others and add to scientific knowledge.

Children (aged 18 and younger) get special protection as research subjects. Almost always, parents must give legal consent for their child to take part in a clinical trial.

When researchers think that a trial's potential risks are greater than minimal, both parents must give permission for their child to enroll. Also, children aged 7 and older often must agree (assent) to take part in clinical trials.

If you agree to have your child take part in a clinical trial, you'll be asked to sign an informed consent form. This form is not a contract. You have the right to withdraw your child from a study at any time, for any reason. Also, you have the right to learn about new risks or findings that emerge during the trial.

For more information about clinical trials related to PDA, talk with your child's doctor. For more information about clinical trials for children, visit the NHLBI's Children and Clinical Studies Web page.

You also can visit the following Web sites to learn more about clinical research and to search for clinical trials:

- http://clinicalresearch.nih.gov

- www.clinicaltrials.gov

- www.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/index.htm

- www.researchmatch.org

Links to Other Information About Patent Ductus Arteriosus

NHLBI Resources

- Congenital Heart Defects (Health Topics)

- How the Heart Works (Health Topics)

- Endocarditis (Health Topics)

- NHLBI-Related Public Interest Organizations

- Story of Success: Congenital Heart Disease

Non-NHLBI Resources

- Congenital Heart Defects (MedlinePlus)

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus (MedlinePlus)

Clinical Trials

- Children and Clinical Studies

- Clinical Trials (Health Topics)

- Current Research (ClinicalTrials.gov)

- NHLBI Clinical Trials

- NIH Clinical Research Trials and You (National Institutes of Health)

- Pediatric Cardiac Genomic Consortium (NHLBI)

- Pediatric Heart Network (NHLBI)

- ResearchMatch (funded by the National Institutes of Health)