General Information

Mortality

Monitoring for Late Effects

Resources to Support Survivor Care

Transition of Survivor Care

During the past five decades, dramatic progress has been made in the development of curative therapy for pediatric malignancies. Long-term survival into adulthood is the expectation for 80% of children with access to contemporary therapies for pediatric malignancies.[1] The therapy responsible for this survival can also produce adverse long-term health-related outcomes, referred to as “late effects,” that manifest months to years after completion of cancer treatment. A variety of approaches have been used to advance knowledge about the very long-term morbidity associated with childhood cancer and its contribution to early mortality. These initiatives have utilized a spectrum of resources including investigation of data from population-based registries, self-reported outcomes provided through large-scale cohort studies, and information collected from medical assessments. Studies reporting outcomes in survivors who have been well characterized in regards to clinical status and treatment exposures, and comprehensively ascertained for specific effects through medical assessments, typically provide the highest quality of data to establish the occurrence and risk profiles for late cancer treatment-related toxicity. Regardless of study methodology, it is important to consider selection and participation bias of the cohort studies in the context of the findings reported.

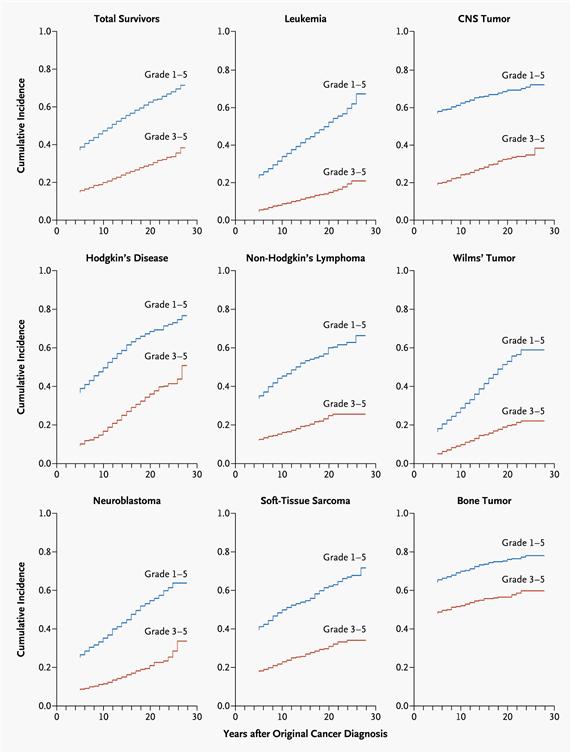

Late effects are commonly experienced by adults who have survived childhood cancer and demonstrate an increasing prevalence associated with longer time elapsed from cancer diagnosis. Population-based studies support excess hospital-related morbidity among childhood cancer survivors compared with age- and gender-matched controls.[3-6] Research has clearly demonstrated that late effects contribute to a high burden of morbidity among adults treated for cancer during childhood, with 60% to almost 90% developing one or more chronic health conditions and 20% to 40% experiencing severe or life-threatening complications during adulthood.[2,7-10] Recognition of late effects, concurrent with advances in cancer biology, radiological sciences, and supportive care, has resulted in a change in the prevalence and spectrum of treatment effects. In an effort to reduce and prevent late effects, contemporary therapy for the majority of pediatric malignancies has evolved to a risk-adapted approach that is assigned based on a variety of clinical, biological, and sometimes genetic factors. With the exception of survivors requiring intensive multimodality therapy for aggressive or refractory/relapsed malignancies, life-threatening treatment effects are relatively uncommon after contemporary therapy in early follow-up (up to 10 years after diagnosis). However, survivors still frequently experience life-altering morbidity related to effects of cancer treatment on endocrine, reproductive, musculoskeletal, and neurologic function.

MortalityLate effects also contribute to an excess risk of premature death among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Several studies of very large cohorts of survivors have reported early mortality among individuals treated for childhood cancer compared with age- and gender-matched general population controls. Relapsed/refractory primary cancer remains the most frequent cause of death, followed by excess cause-specific mortality from subsequent primary cancers and cardiac and pulmonary toxicity.[11-17]; [18][Level of evidence: 3iA] Despite high premature morbidity rates, overall mortality has decreased over time.[19,20] This reduction is related to a decrease in deaths from the primary cancer without an associated increase in mortality from subsequent cancers or treatment-related toxicities. The former reflects improvements in therapeutic efficacy, and the latter reflects changes in therapy made subsequent to studying the causes of late effects. The expectation that mortality rates in survivors will continue to exceed those in the general population is based on the long-term sequelae that are likely to increase with attained age. If patients treated on therapeutic protocols are followed for long periods into adulthood, it will be possible to evaluate the excess lifetime mortality in relation to specific therapeutic interventions.

Monitoring for Late EffectsRecognition of both acute and late modality–specific toxicity has motivated investigations evaluating the pathophysiology and prognostic factors for cancer treatment–related effects. The results of these studies have played an important role in changing pediatric cancer therapeutic approaches and reducing treatment-related mortality among survivors treated in more recent eras.[19,20] These investigations have also informed the development of risk counseling and health screening recommendations of long-term survivors by identifying the clinical and treatment characteristics of those at highest risk for treatment complications. The common late effects of pediatric cancer encompass several broad domains including growth and development, organ function, reproductive capacity and health of offspring, and secondary carcinogenesis. In addition, survivors of childhood cancer may experience a variety of adverse psychosocial sequelae related to the primary cancer, its treatment, or maladjustment associated with the cancer experience.

Late sequelae of therapy for childhood cancer can be anticipated based on therapeutic exposures, but the magnitude of risk and the manifestations in an individual patient are influenced by numerous factors. Factors that should be considered in the risk assessment for a given late effect include the following:

Tumor-related factors

- Tumor location.

- Direct tissue effects.

- Tumor-induced organ dysfunction.

- Mechanical effects.

Treatment-related factors

- Radiation therapy: total dose, fraction size, organ or tissue volume, type of machine energy.

- Chemotherapy: agent type, dose-intensity, cumulative dose, schedule.

- Surgery: technique, site.

- Use of combined modality therapy.

- Blood product transfusion.

- Hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Host-related factors

- Gender.

- Age at diagnosis.

- Time from diagnosis/therapy.

- Developmental status.

- Genetic predisposition.

- Inherent tissue sensitivities and capacity for normal tissue repair.

- Function of organs not affected by cancer treatment.

- Premorbid health state.

- Socioeconomic status.

- Health habits.

The need for long-term follow-up for childhood cancer survivors is supported by the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG), and the Institute of Medicine. Specifically, a risk-based medical follow-up is recommended, which includes a systematic plan for lifelong screening, surveillance, and prevention that incorporates risk estimates based on the previous cancer, cancer therapy, genetic predisposition, lifestyle behaviors, and comorbid conditions.[21,22] Part of long-term follow-up should also be focused on appropriate screening of educational and vocational progress. Specific treatments for childhood cancer, especially those that directly impact nervous system structures, may result in sensory, motor, and neurocognitive deficits that may have adverse consequences on functional status, educational attainment, and future vocational opportunities.[23] A Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) investigation observed that treatment with cranial radiation doses of 25 Gy or higher was associated with higher odds of unemployment (health related: odds ratio [OR] = 3.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.54–4.74; seeking work: OR = 1.77; 95% CI, 1.15–2.71).[24] Unemployed survivors reported higher levels of poor physical functioning than employed survivors, had lower education and income, and were more likely to be publicly insured than unemployed siblings.[24] These data emphasize the importance of facilitating survivor access to remedial services, which has been demonstrated to have a positive impact on education achievement,[25] which may in turn enhance vocational opportunities.

In addition to risk-based screening for medical late effects, the impact of health behaviors on cancer-related health risks should also be emphasized. Health-promoting behaviors should be stressed for survivors of childhood cancer, as targeted educational efforts appear to be worthwhile.[26-29] Smoking, excess alcohol use, and illicit drug use increase risk of organ toxicity and, potentially, subsequent neoplasms. Unhealthy dietary practices and sedentary lifestyle may exacerbate treatment-related metabolic and cardiovascular complications. Proactively addressing unhealthy and risky behaviors is pertinent, as several research investigations confirm that long-term survivors use tobacco and alcohol and have inactive lifestyles at higher rates than is ideal given their increased risk of cardiac, pulmonary, and metabolic late effects.[30-32]

Unfortunately, the majority of childhood cancer survivors do not receive recommended risk-based care. The CCSS reported that 88.8% of survivors were receiving some form of medical care; however, only 31.5% reported receiving care that focused on their prior cancer (survivor-focused care), and 17.8% reported receiving survivor-focused care that included advice about risk reduction and discussion or ordering of screening tests.[30] Among the same cohort, surveillance for new cases of cancer was very low in survivors at the highest risk for colon, breast, or skin cancer, suggesting that survivors and their physicians need education about their risks and recommended surveillance.[33] Health insurance access appears to play an important role in access to risk-based survivor care. In a related CCSS study, uninsured survivors were less likely than those privately insured to report a cancer-related visit (adjusted relative risk [RR] = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.75–0.91) or a cancer center visit (adjusted RR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.71–0.98). Uninsured survivors had lower levels of utilization in all measures of care compared with privately insured survivors. In contrast, publicly insured survivors were more likely to report a cancer-related visit (adjusted RR = 1.22; 95% CI, 1.11–1.35) or a cancer center visit (adjusted RR = 1.41; 95% CI, 1.18–1.70) than were privately insured survivors.[34] Overall, lack of health insurance remains a significant concern for survivors of childhood cancer because of health issues, unemployment, and other societal factors. Legislation, like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act legislation, has improved access and retention of health insurance among survivors, although the quality and limitations associated with these policies have not been well studied.[35,36]

Transition of Survivor CareTransition of care from the pediatric to the adult health care setting is necessary for most childhood cancer survivors in the United States. When available, multidisciplinary long-term follow-up (LTFU) programs in the pediatric cancer center work collaboratively with community physicians to provide care for childhood cancer survivors. This type of shared-care has been proposed as the optimal model to facilitate coordination between the cancer center oncology team and community physician groups providing survivor care.[37] An essential service of LTFU programs is the organization of an individualized survivorship care plan that includes details about therapeutic interventions undertaken for childhood cancer and their potential health risks, personalized health screening recommendations, and information about lifestyle factors that modify risks. For survivors who have not been provided with this information, the COG offers a template that can be used by survivors to organize a personal treatment summary (see the COG Survivorship Guidelines Appendix 1).

To facilitate survivor and provider access to succinct information to guide risk-based care, COG investigators have organized a compendium of exposure- and risk-based health surveillance recommendations with the goal of standardizing the care of childhood cancer survivors.[21] The COG Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers are appropriate for asymptomatic survivors presenting for routine exposure-based medical follow-up 2 or more years after completion of therapy. Patient education materials called ‘‘Health Links’’ provide detailed information on guideline-specific topics to enhance health maintenance and promotion among this population of cancer survivors.[38] Multidisciplinary system-based (e.g., cardiovascular, neurocognitive, and reproductive) task forces who are responsible for monitoring the literature, evaluating guideline content, and providing recommendations for guideline revisions as new information becomes available have also published several comprehensive reviews that address specific late effects of childhood cancer.[39-47] Information concerning late effects is summarized in tables throughout this summary.

References

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al.: Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin 60 (5): 277-300, 2010 Sep-Oct. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al.: Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 355 (15): 1572-82, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lorenzi MF, Xie L, Rogers PC, et al.: Hospital-related morbidity among childhood cancer survivors in British Columbia, Canada: report of the childhood, adolescent, young adult cancer survivors (CAYACS) program. Int J Cancer 128 (7): 1624-31, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mols F, Helfenrath KA, Vingerhoets AJ, et al.: Increased health care utilization among long-term cancer survivors compared to the average Dutch population: a population-based study. Int J Cancer 121 (4): 871-7, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sun CL, Francisco L, Kawashima T, et al.: Prevalence and predictors of chronic health conditions after hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood 116 (17): 3129-39; quiz 3377, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rebholz CE, Reulen RC, Toogood AA, et al.: Health care use of long-term survivors of childhood cancer: the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 29 (31): 4181-8, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, et al.: Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 297 (24): 2705-15, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wasilewski-Masker K, Mertens AC, Patterson B, et al.: Severity of health conditions identified in a pediatric cancer survivor program. Pediatr Blood Cancer 54 (7): 976-82, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Stevens MC, Mahler H, Parkes S: The health status of adult survivors of cancer in childhood. Eur J Cancer 34 (5): 694-8, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Garrè ML, Gandus S, Cesana B, et al.: Health status of long-term survivors after cancer in childhood. Results of an uniinstitutional study in Italy. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 16 (2): 143-52, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al.: Late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: a summary from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 27 (14): 2328-38, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bhatia S, Robison LL, Francisco L, et al.: Late mortality in survivors of autologous hematopoietic-cell transplantation: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood 105 (11): 4215-22, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dama E, Pastore G, Mosso ML, et al.: Late deaths among five-year survivors of childhood cancer. A population-based study in Piedmont Region, Italy. Haematologica 91 (8): 1084-91, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lawless SC, Verma P, Green DM, et al.: Mortality experiences among 15+ year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48 (3): 333-8, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- MacArthur AC, Spinelli JJ, Rogers PC, et al.: Mortality among 5-year survivors of cancer diagnosed during childhood or adolescence in British Columbia, Canada. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48 (4): 460-7, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Möller TR, Garwicz S, Perfekt R, et al.: Late mortality among five-year survivors of cancer in childhood and adolescence. Acta Oncol 43 (8): 711-8, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tukenova M, Guibout C, Hawkins M, et al.: Radiation therapy and late mortality from second sarcoma, carcinoma, and hematological malignancies after a solid cancer in childhood. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 80 (2): 339-46, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Reulen RC, Winter DL, Frobisher C, et al.: Long-term cause-specific mortality among survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 304 (2): 172-9, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Armstrong GT, Pan Z, Ness KK, et al.: Temporal trends in cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 28 (7): 1224-31, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yeh JM, Nekhlyudov L, Goldie SJ, et al.: A model-based estimate of cumulative excess mortality in survivors of childhood cancer. Ann Intern Med 152 (7): 409-17, W131-8, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al.: Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: the Children's Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children's Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol 22 (24): 4979-90, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM: Long-term complications following childhood and adolescent cancer: foundations for providing risk-based health care for survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 54 (4): 208-36, 2004 Jul-Aug. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hudson MM, Mulrooney DA, Bowers DC, et al.: High-risk populations identified in Childhood Cancer Survivor Study investigations: implications for risk-based surveillance. J Clin Oncol 27 (14): 2405-14, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kirchhoff AC, Leisenring W, Krull KR, et al.: Unemployment among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Med Care 48 (11): 1015-25, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mitby PA, Robison LL, Whitton JA, et al.: Utilization of special education services and educational attainment among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 97 (4): 1115-26, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cox CL, McLaughlin RA, Rai SN, et al.: Adolescent survivors: a secondary analysis of a clinical trial targeting behavior change. Pediatr Blood Cancer 45 (2): 144-54, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cox CL, McLaughlin RA, Steen BD, et al.: Predicting and modifying substance use in childhood cancer survivors: application of a conceptual model. Oncol Nurs Forum 33 (1): 51-60, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cox CL, Montgomery M, Oeffinger KC, et al.: Promoting physical activity in childhood cancer survivors: results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 115 (3): 642-54, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cox CL, Montgomery M, Rai SN, et al.: Supporting breast self-examination in female childhood cancer survivors: a secondary analysis of a behavioral intervention. Oncol Nurs Forum 35 (3): 423-30, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nathan PC, Ford JS, Henderson TO, et al.: Health behaviors, medical care, and interventions to promote healthy living in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol 27 (14): 2363-73, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schultz KA, Chen L, Chen Z, et al.: Health and risk behaviors in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 55 (1): 157-64, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tercyak KP, Donze JR, Prahlad S, et al.: Multiple behavioral risk factors among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer in the Survivor Health and Resilience Education (SHARE) program. Pediatr Blood Cancer 47 (6): 825-30, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nathan PC, Ness KK, Mahoney MC, et al.: Screening and surveillance for second malignant neoplasms in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Ann Intern Med 153 (7): 442-51, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Casillas J, Castellino SM, Hudson MM, et al.: Impact of insurance type on survivor-focused and general preventive health care utilization in adult survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). Cancer 117 (9): 1966-75, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Crom DB, Lensing SY, Rai SN, et al.: Marriage, employment, and health insurance in adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 1 (3): 237-45, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pui CH, Cheng C, Leung W, et al.: Extended follow-up of long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 349 (7): 640-9, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS: Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 24 (32): 5117-24, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Eshelman D, Landier W, Sweeney T, et al.: Facilitating care for childhood cancer survivors: integrating children's oncology group long-term follow-up guidelines and health links in clinical practice. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 21 (5): 271-80, 2004 Sep-Oct. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Castellino S, Muir A, Shah A, et al.: Hepato-biliary late effects in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 54 (5): 663-9, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Henderson TO, Amsterdam A, Bhatia S, et al.: Systematic review: surveillance for breast cancer in women treated with chest radiation for childhood, adolescent, or young adult cancer. Ann Intern Med 152 (7): 444-55; W144-54, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jones DP, Spunt SL, Green D, et al.: Renal late effects in patients treated for cancer in childhood: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51 (6): 724-31, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Liles A, Blatt J, Morris D, et al.: Monitoring pulmonary complications in long-term childhood cancer survivors: guidelines for the primary care physician. Cleve Clin J Med 75 (7): 531-9, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nandagopal R, Laverdière C, Mulrooney D, et al.: Endocrine late effects of childhood cancer therapy: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Horm Res 69 (2): 65-74, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nathan PC, Patel SK, Dilley K, et al.: Guidelines for identification of, advocacy for, and intervention in neurocognitive problems in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161 (8): 798-806, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ritchey M, Ferrer F, Shearer P, et al.: Late effects on the urinary bladder in patients treated for cancer in childhood: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 52 (4): 439-46, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shankar SM, Marina N, Hudson MM, et al.: Monitoring for cardiovascular disease in survivors of childhood cancer: report from the Cardiovascular Disease Task Force of the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatrics 121 (2): e387-96, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wasilewski-Masker K, Kaste SC, Hudson MM, et al.: Bone mineral density deficits in survivors of childhood cancer: long-term follow-up guidelines and review of the literature. Pediatrics 121 (3): e705-13, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

Back to Top

Back to Top