Climate Change

International Impacts & Adaptation

International Impacts & Adaptation

International Climate Impacts

On This Page

Key Points

- Countries around the world will likely face climate change impacts that affect a wide variety of sectors, from water resources to human health to ecosystems.

- Impacts will vary by region and by population.

- Many people in developing countries are more vulnerable to climate change impacts than people in developed countries.

- Impacts across the globe can have national security implications for the United States and other nations.

Related Links

EPA:

Other:

-

IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, Working Group II

-

NRC America's Climate Choices: Advancing the Science of Climate Change

-

United Nations Environment Programme

-

World Meteorological Organization

-

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO)

-

United Kingdom Climate Impacts Program

- U.S. Department of State

- U.S. Agency for International Development

-

The World Bank

-

Arctic Council, Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report

Introduction to Global Issues

Many global issues are climate-related, including basic needs such as food, water, health, and shelter. Changes in climate may threaten these needs with increased temperatures, sea level rise, changes in precipitation, and more frequent or intense extreme events.

Climate change will affect individuals and groups differently. Certain groups of people are particularly sensitive to climate change impacts, such as the elderly, the infirm, children, native and tribal groups, and low-income populations.

Climate change may also threaten key natural resources, affecting water and food security. Conflicts, mass migrations, health impacts, or environmental stresses in other parts of the world could raise national security issues for the United States. [1] [2]

Farmers need access to weather and market information to make decisions, especially as climate change alters historical patterns. Source: USAID

Although climate change is an inherently global issue, the impacts will not be felt equally across the planet. Impacts are likely to differ in both magnitude and rate of change in different continents, countries, and regions. Some nations will likely experience more adverse effects than others. Other nations may benefit from climate changes. The capacity to adapt to climate change can influence how climate change affects individuals, communities, countries, and the global population.

Impacts on Basic Needs: Food, Water, Health, and Shelter

Impacts on Agriculture and Food

Changes in climate could have significant impacts on food production around the world. Heat stress, droughts, and flooding events may lead to reductions in crop yields and livestock productivity. Areas that are already affected by drought, such as Australia and the Sahel in Africa, will likely experience reductions in water available for irrigation. [1]

At mid to high latitudes, cereal crop yields are projected to increase slightly, depending on local rates of warming and crop type. At lower latitudes, cereal crop yields are projected to decrease. The greatest decreases in crop yields will likely occur in dry and tropical regions. In some African countries, for example, yields from rain-fed agriculture in drought years could decline by as much as 50% by 2020. This decline will likely be exacerbated by climate change. [3] [4]

Climate change has already affected many fisheries around the world. Increasing ocean temperatures have shifted some marine species to cooler waters outside of their normal range. Fisheries are important for the food supply and economy of many countries. For example, more than 40 million people rely on the fisheries in the Lower Mekong delta in Asia. Projected reductions in water flows and increases in sea level may negatively affect water quality and fish species in this region. This would affect the food supply for communities that depend on these resources. [4] [5]

For more information about the impacts of climate change on agriculture and food production, please visit the Agriculture and Food Supply Impacts & Adaptation page.

Impacts on Water Supply and Quality

Semi-arid and arid areas (such as the Mediterranean, southern Africa, and northeastern Brazil) are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change on water supply. Over the next century, these areas will likely experience decreases in water resources, especially in areas that are already water-stressed due to droughts, population pressures, and water resource extraction. [1] [5] [6]

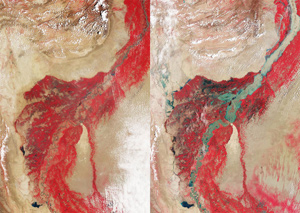

Indus River in Southern Pakistan (Left: August 2009; Right: August 2010). In August 2010, record monsoon rains flooded significant portions of Pakistan. The floods forced 6 million Pakistanis to flee their homes and affected about 20 million people in some way. In the image from 2009, the Indus is about 0.6 miles wide. In the 2010 image, the river is 14 miles wide or more in parts. Photo Source: NASA (2010) Text Source: NOAA (2010)

View enlarged image

View enlarged image

Areas in Africa currently at risk for (a) hunger, (b) natural hazard-related disaster risks, (c) malaria (derived from historical rainfall and temperature data [1950-1996]), and (d) epidemics of meningococcal meningitis (based on epidemic experience, relative humidity [1961-1990] and land cover). Source: IPCC (2007) (PDF)

![]()

The availability of water resources is strongly related to the amount and timing of runoff and precipitation. By 2050, annual average river runoff is projected to increase by 10-40% at high latitudes and in some wet tropical areas, but decrease by 10-30% in some dry regions at mid-latitudes and in the subtropics. As temperatures rise, snowpack is declining in many regions and glaciers are melting at unprecedented rates, increasing flood risks. Droughts are likely to become more widespread, while increases in heavy precipitation events would produce more flooding. [4] [6]

Water quality is important for ecosystems, human health and sanitation, agriculture, and other purposes. Increases in temperature, changes in precipitation, sea level rise, and extreme events could diminish water quality in many regions. In particular, saltwater from rising sea level and storm surges threaten water supplies in coastal areas and on small islands. Additionally, increasing water temperatures can cause algal blooms and potentially increase bacteria in water bodies. These impacts may require communities to begin treating their water in order to provide safe water resources for human uses. [6]

For more information about the impacts of climate change on the water supply, please visit the Water Impacts & Adaptation page.

Impacts on Human Health

The risks of climate-sensitive diseases and health impacts can be high in poor countries that have little capacity to prevent and treat illness. There are many examples of health impacts related to climate change.

- Sustained increases in temperatures are linked to more frequent and severe heat stress.

- The reduction in air quality that often accompanies a heat wave can lead to breathing problems and worsen respiratory diseases.

- Impacts of climate change on agriculture and other food systems can increase rates of malnutrition. [7]

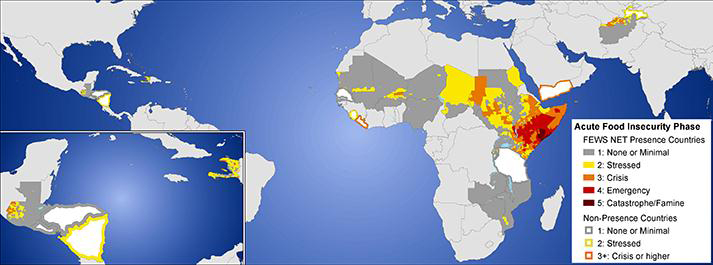

- Climate changes can influence infectious diseases. The spread of meningococcal (epidemic) meningitis is often linked to climate changes, especially drought. Areas of sub-Saharan and West Africa are sensitive to the spread of meningitis, and will be particularly at-risk if droughts become more frequent and severe. [7]

- The spread of mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria may increase in areas projected to receive more precipitation and flooding. Increases in rainfall and temperature can cause spreading of dengue fever. [7]

Certain groups of people in low-income countries are especially at risk for adverse health effects from climate change. These at-risk groups include the urban poor, older adults, young children, traditional societies, subsistence farmers, and coastal populations. Many regions, such as Europe, South Asia, Australia, and North America, have experienced heat-related health impacts. Rural populations, older adults, outdoor workers, and those without access to air conditioning are often the most vulnerable to heat-related illness and death. [7] For more information about the climate impacts on vulnerable populations, please visit the Society Impacts & Adaptation page.

Impacts on Shelter

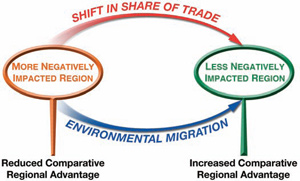

General effects of climate change on international trade and migration: regions with greater net benefits from climate change are likely to show trade benefits, along with environmental in-migration (IPCC). Source: IPCC (2007) (PDF)

![]()

Climate change may affect the migration of people within and between countries around the world. A variety of reasons may force people to migrate into other areas. These reasons include conflicts, such as ethnic or resource conflicts, and extreme events, such as flooding, drought, and hurricanes. Extreme events displace many people, especially in areas that do not have the ability or resources to quickly respond or rebuild after disasters. Extreme events may become more frequent and severe because of climate change. This could increase the numbers of people migrating during and after these types of events. [8]

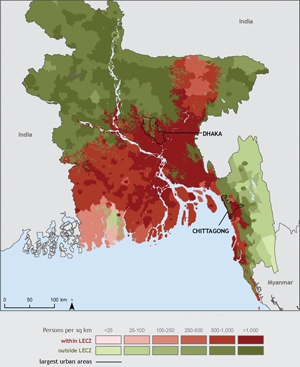

Coastal settlements are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts, such as sea level rise and extreme storms. As coastal habitats (such as barrier islands, wetlands, deltas, and estuaries) are destroyed, coastal settlements can become more vulnerable to flooding from storm surges. Both developing and developed countries are vulnerable to the impacts of sea level rise. For example, the Netherlands, Guyana, and Bangladesh are low-lying countries that are particularly at-risk. [9]

For more information about the impacts of climate change on coastal areas, please visit the Coastal Impacts & Adaptation page.

Relative vulnerability of coastal deltas as shown by the population potentially displaced by current sea-level trends to 2050 (Extreme = >1 million people displaced; High = 1 million to 50,000; Medium = 50,000 to 5,000). Source: IPCC (2007) (PDF)

![]()

Megacities

For the first time in human history, more people are living in cities than in rural areas. The term "megacities" refers to cities with populations over 10 million. Fifteen of the world's 20 megacities are sensitive to sea level rise and increased coastal storm surges. A recent study by the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, and the Japan International Cooperation Agency looked at the effects of climate change on three of Asia's megacities. The study estimated that 26% of the population in Ho Chi Minh City is currently affected by extreme storm events. By 2050, this number could climb to more than 60%. In Metro Manila, a major flood under a worst-case scenario could result in the loss of nearly a quarter of the gross domestic product (GDP) of the metropolitan area. Manila faces not only sea level rise and extreme rainfall events but also typhoons. The study concluded that such climate-related risks must be an integral part of city and regional planning for sensitive megacities.

Sources:

ADB, JICA, and World Bank, 2010: Climate Risks and Adaptation in Asian Coastal Megacities, A Synthesis Report. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, Washington, DC. (PDF)

![]()

World Bank, 2010: Cities and Climate Change: An Urgent Agenda. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, Washington, DC.

![]()

Impacts on Vulnerable Populations

Three women reach their water source, a low water level lake in India. Photo Credit: 2006, Joydeep Mukherjee, Courtesy of Photoshare. Source: USAID

Indigenous groups in various regions--such as Latin and South America, Europe, and Africa--are already experiencing threats to their traditional livelihoods. Rising sea levels and extreme events threaten native groups that inhabit low-lying island nations. Higher temperatures and reduced snow and ice threaten groups that live in mountainous and polar areas. Climate effects in these areas can affect hunting, fishing, transport, and other activities. [8]

About 1.4 billion people live below the World Bank's measure of extreme poverty, earning less than US$1.25 a day. This represents about one quarter of the population of the developing world. [10] Many lower-income groups depend on publicly provided resources and services such as water, energy, and transportation. Extreme events can affect and disrupt these resources and services, sometimes beyond replacement or repair. Many people in lower-income countries also cannot afford or gain access to adaptation mechanisms such as air conditioning, heating, or climate-risk insurance. [8]

Older and younger people are also especially sensitive to climate change impacts. Children's developing immune, respiratory, and neurological systems make them more sensitive to some climate change impacts, including extreme events, heat, and disease. [1] [8] Elderly populations are also at risk due to frail health and limited mobility. Extreme heat and storm events can disproportionately affect older people. [11]

Climate change impacts will also differ according to gender. Women in developing countries are especially vulnerable. The ratio of women (to the total population) affected or killed by climate-related disasters is already higher in some developing countries than in developed countries. [8]

For more information about the impacts of climate change on vulnerable populations, please visit the Society Impacts & Adaptation page.

Impacts on National Security

Climate change impacts have the potential to exacerbate national security issues and increase the number of international conflicts. [1]

Water scarcity led to tensions in southern Kazakhstan. USAID responded by increasing access to drinking water and irrigation. Source: USAID

Many concerns revolve around the use of natural resources, such as water. In many parts of the world, water issues cross national borders. Access to consistent and reliable sources of water in these regions is greatly valued. Changes in the timing and intensity of rainfall would threaten already limited water sources and potentially cause future conflicts. [1]

Threatened food security in parts of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa could also lead to conflict. Rapid population growth and changes in precipitation and temperature, among other factors, are already affecting crop yields. Resulting food shortages could increase the risk of humanitarian crises and trigger population migration across national borders, ultimately sparking political instability. [1] [3] [7] [11]

Increased melting of ice in the Arctic Ocean is a very likely climate change impact with national security implications. The Arctic Ocean has a long history of modest, though growing, shipping activity, including trans-Arctic shipping routes. Declining sea ice coverage will improve access to these waters. However, a number of other international issues will influence the potential growth in shipping. In the case of the Arctic Ocean, increasing access to these waters means that issues of sovereignty (priority in control over an area), security (responsibility for policing the passageways), environmental protection (control of ship-based air and water pollution, noise, or ship strikes of whales), and safety (responsibility for rescue and response) will become more important. [12]

Regional Impacts

Highlights of recent and projected regional impacts are shown below.

Impacts on Africa [3]

- Africa is one of the most vulnerable continents to climate variability and change because of multiple existing stresses and low adaptive capacity. Existing stresses include poverty, political conflicts, and ecosystem degradation.

- By 2050, between 350 million and 600 million people are projected to experience increased water stress due to climate change.

- Climate variability and change is projected to severely compromise agricultural production, including access to food, in many African countries and regions.

- Toward the end of the 21st century, projected sea level rise will likely affect low-lying coastal areas with large populations.

- Climate variability and change can negatively impact human health. In many African countries, other factors already threaten human health. For example, malaria threatens health in southern Africa and the East African highlands.

Impacts on Asia [5]

- Glaciers in Asia are melting at a faster rate than ever documented in historical records. Melting glaciers increase the risks of flooding and rock avalanches from destabilized slopes.

- Climate change is projected to decrease freshwater availability in central, south, east and southeast Asia, particularly in large river basins. With population growth and increasing demand from higher standards of living, this decrease could adversely affect more than a billion people by the 2050s.

- Increased flooding from the sea and, in some cases, from rivers, threatens coastal areas, especially heavily populated delta regions in south, east, and southeast Asia.

- By the mid-21st century, crop yields could increase up to 20% in east and southeast Asia. In the same period, yields could decrease up to 30% in central and south Asia.

- Sickness and death due to diarrheal disease are projected to increase in east, south, and southeast Asia due to projected changes in the hydrological cycle associated with climate change.

Impacts on Australia and New Zealand [13]

- Water security problems are projected to intensify by 2030 in southern and eastern Australia, and in the northern and some eastern parts of New Zealand.

- Significant loss of biodiversity is projected to occur by 2020 in some ecologically rich sites, including the Great Barrier Reef and Queensland Wet Tropics.

- Sea level rise and more severe storms and coastal flooding will likely impact coastal areas. Coastal development and population growth in areas such as Cairns and Southeast Queensland (Australia) and Northland to Bay of Plenty (New Zealand), would place more people and infrastructure at risk.

- By 2030, increased drought and fire is projected to cause declines in agricultural and forestry production over much of southern and eastern Australia and parts of eastern New Zealand.

- Extreme storm events are likely to increase failure of floodplain protection and urban drainage and sewerage, as well as damage from storms and fires.

- More heat waves may cause more deaths and more electrical blackouts.

Impacts on Europe [14]

- Wide-ranging impacts of climate change have already been documented in Europe. These impacts include retreating glaciers, longer growing seasons, species range shifts, and heat wave-related health impacts.

- Future impacts of climate change are projected to negatively affect nearly all European regions. Many economic sectors, such as agriculture and energy, could face challenges.

- In southern Europe, higher temperatures and drought may reduce water availability, hydropower potential, summer tourism, and crop productivity.

- In central and eastern Europe, summer precipitation is projected to decrease, causing higher water stress. Forest productivity is projected to decline. The frequency of peatland fires is projected to increase.

- In northern Europe, climate change is initially projected to bring mixed effects, including some benefits such as reduced demand for heating, increased crop yields, and increased forest growth. However, as climate change continues, negative impacts are likely to outweigh benefits. These include more frequent winter floods, endangered ecosystems, and increasing ground instability.

Impacts on Latin America [15]

- By mid-century, increases in temperature and decreases in soil moisture are projected to cause savanna to gradually replace tropical forest in eastern Amazonia.

- In drier areas, climate change will likely worsen drought, leading to salinization (increased salt content) and desertification (land degradation) of agricultural land. The productivity of livestock and some important crops such as maize and coffee is projected to decrease, with adverse consequences for food security. In temperate zones, soybean yields are projected to increase.

- Sea level rise is projected to increase risk of flooding, displacement of people, salinization of drinking water resources, and coastal erosion in low-lying areas.

- Changes in precipitation patterns and the melting of glaciers are projected to significantly affect water availability for human consumption, agriculture, and energy generation.

Impacts on North America [16]

- Warming in western mountains is projected to decrease snowpack, increase winter flooding, and reduce summer flows, exacerbating competition for over-allocated water resources.

- Disturbances from pests, diseases, and fire are projected to increasingly affect forests, with extended periods of high fire risk and large increases in area burned.

- Moderate climate change in the early decades of the century is projected to increase aggregate yields of rain-fed agriculture by 5-20%, but with important variability among regions. Crops that are near the warm end of their suitable range or that depend on highly utilized water resources will likely face major challenges.

- Increases in the number, intensity, and duration of heat waves during the course of the century are projected to further challenge cities that currently experience heat waves, with potential for adverse health impacts. Older populations are most at risk.

- Climate change will likely increasingly stress coastal communities and habitats, worsening the existing stresses of development and pollution.

Impacts on Polar Regions [17]

- Climate changes will likely reduce the thickness and extent of glaciers and ice sheets.

- Changes in natural ecosystems will likely have detrimental effects on many organisms including migratory birds, mammals, and higher predators.

- In the Arctic, climate changes will likely reduce the extent of sea ice and permafrost, which can have mixed effects on human settlements. Negative impacts could include damage to infrastructure and changes to winter activities such as ice fishing and ice road transportation. Positive impacts could include more navigable northern sea routes.

- The reduction and melting of permafrost, sea level rise, and stronger storms may worsen coastal erosion.

- Terrestrial and marine ecosystems and habitats are projected to be at risk to invasive species, as climatic barriers are lowered in both polar regions.

Impacts on Small Islands [18]

- Small islands, whether located in the tropics or higher latitudes, are already exposed to extreme events and changes in sea level. This existing exposure will likely make these areas sensitive to the effects of climate change.

- Deterioration in coastal conditions, such as beach erosion and coral bleaching, will likely affect local resources such as fisheries, as well as the value of tourism destinations.

- Sea level rise is projected to worsen inundation, storm surge, erosion, and other coastal hazards. These impacts would threaten vital infrastructure, settlements, and facilities that support the livelihood of island communities.

- By mid-century, on many small islands (such as the Caribbean and Pacific), climate change is projected to reduce already limited water resources to the point that they become insufficient to meet demand during low-rainfall periods.

- Invasion by non-native species is projected to increase with higher temperatures, particularly in mid- and high-latitude islands.

To learn more about international adaptation measures, please see the international adaptation section.

References

1. NRC (2010). Advancing the Science of Climate Change

.

![]() National Research Council. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA.

National Research Council. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA.

2. USGCRP (2009). Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States . Karl, T.R. J.M. Melillo, and T.C. Peterson (eds.). United States Global Change Research Program. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA.

3. Boko, M., I. Niang, A. Nyong, C. Vogel, A. Githeko, M. Medany, B. Osman-Elasha, R. Tabo and P. Yanda (2007). Africa. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden, and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden, and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

4. Easterling, W.E., P.K. Aggarwal, P. Batima, K.M. Brander, L. Erda, S.M. Howden, A. Kirilenko, J. Morton, J.-F. Soussana, J. Schmidhuber, and F.N. Tubiello (2007). Food, Fibre, and Forest Products. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden, and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden, and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

5. Cruz, R.V., H. Harasawa, M. Lal, S. Wu, Y. Anokhin, B. Punsalmaa, Y. Honda, M. Jafari, C. Li and N. Huu Ninh (2007). Asia. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

6. Kundzewicz, Z.W., L.J. Mata, N.W. Arnell, P. Döll, P. Kabat, B. Jiménez, K.A. Miller, T. Oki, Z. Sen and I.A. Shiklomanov (2007). Fresh Water Resources and Their Management. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

7. Confalonieri, U., B. Menne, R. Akhtar, K.L. Ebi, M. Hauengue, R.S. Kovats, B. Revich and A. Woodward (2007). Human Health. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, (eds.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, (eds.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

8. Wilbanks, T.J., P. Romero Lankao, M. Bao, F. Berkhout, S. Cairncross, J.-P. Ceron, M. Kapshe, R. Muir-Wood and R. Zapata-Marti (2007). Industry, Settlement and Society. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

9. Nicholls, R.J., P.P. Wong, V.R. Burkett, J.O. Codignotto, J.E. Hay, R.F. McLean, S. Ragoonaden and C.D. Woodroffe (2007). Coastal Systems and Low-Lying Areas. In: Climate

Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability

.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

10. World Bank, 2011: World Development Indicators 2011.

![]()

11. CCSP (2008). Analyses of The Effects of Global Change On Human Health and Welfare and Human Systems. A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Gamble, J.L. (ed.), K.L. Ebi, F.G. Sussman, T.J. Wilbanks, (Authors). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA.

12.

Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report (PDF).

![]() Arctic Council, April 2009, second printing.

Arctic Council, April 2009, second printing.

13. Hennessy, K., B. Fitzharris, B.C. Bates, N. Harvey, S.M. Howden, L. Hughes, J. Salinger and R. Warrick (2007). Australia and New Zealand. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

14. Alcamo, J., J.M. Moreno, B. Nováky, M. Bindi, R. Corobov, R.J.N. Devoy, C. Giannakopoulos, E. Martin, J.E. Olesen, A. Shvidenko (2007). Europe. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

15. Magrin, G., C. Gay García, D. Cruz Choque, J.C. Giménez, A.R. Moreno, G.J. Nagy, C. Nobre and A. Villamizar (2007). Latin America. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

16. Field, C.B., L.D. Mortsch, M. Brklacich, D.L. Forbes, P. Kovacs, J.A. Patz, S.W. Running and M.J. Scott (2007). North America. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

17. Anisimov, O.A., D.G. Vaughan, T.V. Callaghan, C. Furgal, H. Marchant, T.D. Prowse, H. Vilhjálmsson and J.E. Walsh (2007). Polar Regions (Arctic and Antarctic). In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, (eds.)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, (eds.)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

18. Mimura, N., L. Nurse, R.F. McLean, J. Agard, L. Briguglio, P. Lefale, R. Payet and G. Sem (2007). Small Islands. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

.

![]() Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L. O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, (eds.)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Parry, M.L. O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, (eds.)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.