Vascular Access for Hemodialysis

On this page:

- What is an arteriovenous fistula?

- What is an arteriovenous graft?

- What is a venous catheter for temporary access?

- What can I expect during hemodialysis?

- What are some possible complications of my vascular access?

- How should I take care of my vascular access?

- Hope through Research

- For More Information

- Acknowledgments

If you are starting hemodialysis treatments in the next several months, you need to work with your health care team to learn how the treatments work and how to get the most from them. One important step before starting regular hemodialysis sessions is preparing a vascular access, which is the site on your body where blood is removed and returned during dialysis. To maximize the amount of blood cleansed during hemodialysis treatments, the vascular access should allow continuous high volumes of blood flow.

A vascular access should be prepared weeks or months before you start dialysis. The early preparation of the vascular access will allow easier and more efficient removal and replacement of your blood with fewer complications.

The three basic kinds of vascular access for hemodialysis are an arteriovenous (AV) fistula, an AV graft, and a venous catheter. A fistula is an opening or connection between any two parts of the body that are usually separate—for example, a hole in the tissue that normally separates the bladder from the bowel. While most kinds of fistula are a problem, an AV fistula is useful because it causes the vein to grow larger and stronger for easy access to the blood system. The AV fistula is considered the best long-term vascular access for hemodialysis because it provides adequate blood flow, lasts a long time, and has a lower complication rate than other types of access. If an AV fistula cannot be created, an AV graft or venous catheter may be needed.

[Top]

What is an arteriovenous fistula?

An AV fistula requires advance planning because a fistula takes a while after surgery to develop—in rare cases, as long as 24 months. But a properly formed fistula is less likely than other kinds of vascular access to form clots or become infected. Also, properly formed fistulas tend to last many years—longer than any other kind of vascular access.

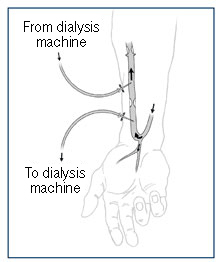

A surgeon creates an AV fistula by connecting an artery directly to a vein, frequently in the forearm. Connecting the artery to the vein causes more blood to flow into the vein. As a result, the vein grows larger and stronger, making repeated needle insertions for hemodialysis treatments easier. For the surgery, you’ll be given a local anesthetic. In most cases, the procedure can be performed on an outpatient basis.

Forearm arteriovenous fistula

[Top]

What is an arteriovenous graft?

If you have small veins that won’t develop properly into a fistula, you can get a vascular access that connects an artery to a vein using a synthetic tube, or graft, implanted under the skin in your arm. The graft becomes an artificial vein that can be used repeatedly for needle placement and blood access during hemodialysis. A graft doesn’t need to develop as a fistula does, so it can be used sooner after placement, often within 2 or 3 weeks.

Compared with properly formed fistulas, grafts tend to have more problems with clotting and infection and need replacement sooner. However, a well-cared-for graft can last several years.

One kind of AV graft

[Top]

What is a venous catheter for temporary access?

If your kidney disease has progressed quickly, you may not have time to get a permanent vascular access before you start hemodialysis treatments. You may need to use a venous catheter as a temporary access.

A catheter is a tube inserted into a vein in your neck, chest, or leg near the groin. It has two chambers to allow a two-way flow of blood. Once a catheter is placed, needle insertion is not necessary.

Catheters are not ideal for permanent access. They can clog, become infected, and cause narrowing of the veins in which they are placed. But if you need to start hemodialysis immediately, a catheter will work for several weeks or months while your permanent access develops.

Venous catheter for temporary hemodialysis access

For some people, fistula or graft surgery is unsuccessful, and they need to use a long-term catheter access. Catheters that will be needed for more than about 3 weeks are designed to be tunneled under the skin to increase comfort and reduce complications. Even tunneled catheters, however, are prone to infection.

[Top]

What can I expect during hemodialysis?

Every hemodialysis session using an AV fistula or AV graft requires needle insertion. Most dialysis centers use two needles—one to carry blood to the dialyzer and one to return the cleansed blood to your body. Some specialized needles are designed with two openings for two-way flow of blood, but these needles are less efficient. For some people, using this needle may mean longer treatments.

Some people prefer to insert their own needles, which requires training to learn how to prevent infection and protect the vascular access. You can also learn a “ladder” strategy for needle placement in which you “climb” up the entire length of the fistula, session by session, so you won’t weaken an area with a grouping of needle sticks.

An alternative approach is the “buttonhole” strategy in which you use a limited number of sites but insert the needle precisely into the same hole made by the previous needle stick. Whether you insert your own needles or not, you should know about these techniques so you can understand and ask questions about your treatments.

[Top]

What are some possible complications of my vascular access?

All three types of vascular access—AV fistula, AV graft, and venous catheter—can have complications that require further treatment or surgery. The most common complications are access infection and low blood flow due to blood clotting in the access.

Venous catheters are most likely to develop infection and clotting problems that may require medication and catheter removal or replacement.

AV grafts can also develop low blood flow, an indication of clotting or narrowing of the access. In this situation, the AV graft may require angioplasty, a procedure to widen the small segment that is narrowed. Another option is to perform surgery on the AV graft and replace the narrow segment.

Infection and low blood flow are much less common in properly formed AV fistulas than in AV grafts and venous catheters. Still, having an AV fistula is not a guarantee against complications.

[Top]

How should I take care of my vascular access?

You can take several steps to protect your access:

- Make sure your nurse or technician checks your access before each treatment.

- Keep your access clean at all times.

- Use your access site only for dialysis.

- Be careful not to bump or cut your access.

- Don’t let anyone put a blood pressure cuff on your access arm.

- Don’t wear jewelry or tight clothes over your access site.

- Don’t sleep with your access arm under your head or body.

- Don’t lift heavy objects or put pressure on your access arm.

- Check the pulse in your access every day.

[Top]

Hope through Research

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) has many research programs aimed at improving the treatment of end-stage renal disease. The NIDDK established the Dialysis Access Consortium, which consists of seven clinical centers and a data coordinating center, to undertake interventional clinical trials to improve outcomes in patients with fistulas and grafts.

Two randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials were designed and are nearly completed. The first trial evaluated the effects of the antiplatelet agent clopidogrel (Plavix) on prevention of early fistula failure. A second clinical trial is studying a drug that combines dipyridamole with aspirin (Aggrenox), with the goal of preventing access stenosis in hemodialysis patients with grafts.

Participants in clinical trials can play a more active role in their own health care, gain access to new research treatments before they are widely available, and help others by contributing to medical research. For information about current studies, visit www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

[Top]

For More Information

Your health care team will help you learn more about how to care for your access site. For a copy of the booklet Getting the Most From Your Treatment: What You Need to Know About Hemodialysis Access, contact

National Kidney Foundation

30 East 33rd Street

New York, NY 10016

Phone: 1–800–622–9010 or 212–889–2210

Internet: www.kidney.org

For a copy of the booklet Understanding Your Hemodialysis Access Options, contact

American Association of Kidney Patients

3505 East Frontage Road, Suite 315

Tampa, FL 33607

Phone: 1–800–749–2257

Email: info@aakp.org

Internet: www.aakp.org

Life Options has developed an interactive patient education website called Kidney School. Module 8 of this program addresses vascular access for hemodialysis. To view this module, go to www.kidneyschool.org or contact

or contact

Life Options

c/o Medical Education Institute, Inc.

414 D’Onofrio Drive, Suite 200

Madison, WI 53719

Phone: 1–800–468–7777

Email: lifeoptions@MEIresearch.org

Internet: www.lifeoptions.org

www.kidneyschool.org

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the End-Stage Renal Disease Networks, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) launched the National Vascular Access Improvement Initiative in 2003. Materials from the Fistula First Change Package are available through the IHI website or by contacting

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

20 University Road, 7th Floor

Cambridge, MA 02138

Phone: 1–866–787–0831 or 617–301–4800

Internet: www.ihi.org

www.fistulafirst.org

Acknowledgments

Publications produced by the Clearinghouse are carefully reviewed by both NIDDK scientists and outside experts.

[Top]

About the Kidney Failure Series

The NIDDK Kidney Failure Series includes booklets and fact sheets that can help the reader learn more about treatment methods for kidney failure, complications of dialysis, financial help for the treatment of kidney failure, and eating right on hemodialysis. Free single printed copies of this series can be obtained by contacting the National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse.

The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. Trade, proprietary, or company names appearing in this document are used only because they are considered necessary in the context of the information provided. If a product is not mentioned, the omission does not mean or imply that the product is unsatisfactory.

[Top]

You may also find additional information about this topic by visiting MedlinePlus at www.medlineplus.gov.

This publication may contain information about medications. When prepared, this publication included the most current information available. For updates or for questions about any medications, contact the U.S. Food and Drug Administration toll-free at 1–888–INFO–FDA (1–888–463–6332) or visit www.fda.gov. Consult your doctor for more information.

[Top]

National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse

3 Information Way

Bethesda, MD 20892–3580

Phone: 1–800–891–5390

TTY: 1–866–569–1162

Fax: 703–738–4929

Email: nkudic@info.niddk.nih.gov

Internet: www.kidney.niddk.nih.gov

The National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NKUDIC) is a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The NIDDK is part of the National Institutes of Health of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Established in 1987, the Clearinghouse provides information about diseases of the kidneys and urologic system to people with kidney and urologic disorders and to their families, health care professionals, and the public. The NKUDIC answers inquiries, develops and distributes publications, and works closely with professional and patient organizations and Government agencies to coordinate resources about kidney and urologic diseases.

This publication is not copyrighted. The Clearinghouse encourages users of this publication to duplicate and distribute as many copies as desired.

NIH Publication No. 08-4554

February 2008

[Top]

Page last updated: September 2, 2010