Testimony

Statement by

Margaret A. Hamburg, M.D.

Commissioner of Food and Drugs

Food and Drug Administration

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

on

Reauthorization of PDUFA: What It Means For Jobs, Innovation, and Patients

before

Subcommittee on Health

Committee on Energy and Commerce

United States House of Representatives

Wednesday February 1, 2012

INTRODUCTION

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Committee, I am Dr. Margaret Hamburg, Commissioner of Food and Drugs at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA or the Agency). I am pleased to be here today to discuss the fifth authorization of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), also referred to as “PDUFA V,” and the renewal of legislation to promote pediatric drug testing. I will also talk about FDA’s efforts to promote the science and innovation necessary to ensure that we are fully equipped to address the public health issues of the 21st century and the continuing challenges of a global marketplace.

Background on PDUFA

FDA considers the timely review of the safety and effectiveness of New Drug Applications (NDA) and Biologics License Applications (BLA) to be central to the Agency’s mission to protect and promote the public health. Prior to enactment of PDUFA in 1992, FDA's review process was understaffed, unpredictable, and slow. FDA lacked sufficient staff to perform timely reviews, or develop procedures and standards to make the process more rigorous, consistent, and predictable. Access to new medicines for U.S. patients lagged behind other countries. As a result of concerns expressed by both industry and patients, Congress enacted PDUFA, which provided the added funds through user fees that enabled FDA to hire additional reviewers and support staff and upgrade its information technology systems. At the same time, FDA committed to complete reviews in a predictable time frame. These changes revolutionized the drug approval process in the United States and enabled FDA to speed the application review process for new drugs, without compromising the Agency’s high standards for demonstration of safety, efficacy, and quality of new drugs prior to approval.

Three fees are collected under PDUFA: application fees, establishment fees, and product fees. An application fee must be submitted when certain NDAs or BLAs are submitted. Product and establishment fees are due annually. The total revenue amounts derived from each of the categories—application fees, establishment fees, and product fees—are set by the statute for each fiscal year (FY). PDUFA permits waivers under certain circumstances, including a waiver of the application fee for small businesses and orphan drugs.

Of the total $931,845,581 obligated in support of the process for the review of human drug applications in FY 2010, PDUFA fees funded 62 percent, with the remainder funded through appropriations.

PDUFA Achievements

PDUFA has produced significant benefits for public health, providing patients faster access to over 1,500 new drugs and biologics, since enactment in 1992, including treatments for cancer, infectious diseases, neurological and psychiatric disorders, and cardiovascular diseases. In FY 2011, FDA approved 35 new, groundbreaking medicines, including two treatments for hepatitis C, a drug for late-stage prostate cancer, the first drug for Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 30 years, and the first drug for lupus in 50 years. Of the 35 innovative drugs approved in FY 2011, 34 met their PDUFA target dates for review.

Substantially Reduced Review Times

PDUFA provides FDA with a source of stable, consistent funding that has made possible our efforts to focus on promoting innovative therapies and help bring to market critical products for patients.

According to researchers at the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, the time required for the FDA approval phase of new drug development (i.e., time from submission until approval) has been cut since the enactment of PDUFA,[1] from an average of 2.0 years for the approval phase at the start of PDUFA to an average of 1.1 years more recently.

FDA aims to review priority drugs more quickly, in six months vs. 10 months for standard drugs. Priority drugs are generally targeted at severe illnesses with few or no available therapeutic options. FDA reviewers give these drugs priority attention throughout development, working with sponsors to determine the most efficient way to collect the data needed to provide evidence of safety and effectiveness.

Reversal of the “Drug Lag”

Importantly, PDUFA has led to the reversal of the drug lag that prompted its creation. Since the enactment of PDUFA, FDA has steadily increased the speed of Americans’ access to important new drugs compared to the European Union (EU) and the world as a whole. Of the 35 innovative drugs approved in FY 2011, 24 (almost 70 percent) were approved by FDA before any other regulatory agency in the world, including the European Medicines Agency. Of 57 novel drugs approved by both FDA and the EU between 2006 and 2010, 43 (75 percent) were approved first in the United States.

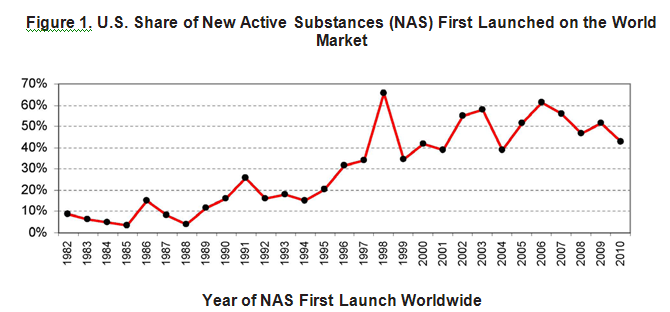

Figure 1 below shows that since the late 1990s, the United States has regularly led the world in the first introduction of new active drug substances.[2] Preliminary data show that in 2011, over half of all new active drug substances were first launched in the United States.

In recent years, FDA’s drug review times also have been, on average, significantly faster than those in the EU. It is difficult to compare length of approvals for FY 2011 because many of the drugs approved in the United States have not yet been approved in the EU. A comparison of drugs approved in the United States and the EU between 2006 and 2010 is illustrative, however. For priority drugs approved between 2006 and 2010, FDA’s median time to approval was six months (183 days), more than twice as fast as the EU, which took a median time of 13.2 months (403 days). For standard drug reviews, FDA’s median time to approval was 13 months (396 days), 53 days faster than the EU time of 14.7 months (449 days).

A recent article in the journal Health Affairs also compared cancer drugs approved in the United States and EU from 2003 through 2010. Thirty-five cancer drugs were approved by the United States or the EU from October 2003 through December 2010. Of those, FDA approved 32—in an average time of 8.6 months (261 days). The EU approved only 26 of these products, and its average time was 12.2 months (373 days). This difference in approval times is not due to safety issues with these products. All 23 cancer drugs approved by both agencies during this period were approved first in the United States.[3]

Providing Guidance to Industry

Increased resources provided by user fees have enabled FDA to provide a large body of technical guidance to industry that clarified the drug development pathway for many diseases and to meet with companies during drug development to provide critical advice on specific development programs. In the past five years alone, FDA has held over 7,000 meetings within a short time after a sponsor’s request. Innovations in drug development are being advanced by many new companies as well as more established ones, and new sponsors may need, and often seek, more regulatory guidance during development. In FY 2009, more than half of the meetings FDA held with companies at the early investigational stage and midway through the clinical trial process were with companies that had no approved product on the U.S. market.

Weighing Benefit and Risk

It should be noted that FDA assesses the benefit-risk of new drugs on a case-by-case basis, considering the degree of unmet medical need and the severity and morbidity of the condition the drug is intended to treat. This approach has been critical to increasing patient access to new drugs for cancer and rare and other serious diseases, where existing therapies have been few and limited in their effectiveness. Some of these products have serious side effects but they were approved because the benefit outweighed the risk. For example, in March of last year, FDA approved Yervoy (ipilimumab) for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Yervoy also poses a risk of serious side effects in 12.9 percent of patients treated with Yervoy, including severe to fatal autoimmune reactions. However, FDA decided that the benefits of Yervoy outweighed its risks, especially considering that no other melanoma treatment has been shown to prolong a patient’s life.

As discussed in more detail below, PDUFA V will enable FDA to develop an enhanced, structured approach to benefit-risk assessments that accurately and concisely describes the benefit and risk considerations in the Agency’s drug regulatory decision-making.

Speeding Access

PDUFA funds help support the use of existing programs to expedite the approval of certain promising investigational drugs, and also to make them available to the very ill as early in the development process as possible, without unduly jeopardizing patient safety. We are committed to using these programs to speed therapies to patients while upholding our high standards of safety and efficacy. Balancing these two objectives requires that we continue to evaluate our use of the tools available to us and consider whether additional tools would be helpful.

The most important of these programs are Priority Review (discussed earlier), Accelerated Approval, and Fast Track. In 1992, FDA instituted the Accelerated Approval process, which allows earlier approval of drugs that treat serious diseases and that fill an unmet medical need based on a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit, but is not fully validated to do so, or, in some cases, an effect on a clinical endpoint other than survival or irreversible morbidity. A surrogate endpoint is a marker—a laboratory measurement, or physical sign—that is used in clinical trials as an indirect or substitute measurement for a clinically meaningful outcome, such as survival or symptom improvement. For example, viral load is a surrogate endpoint for approval of drugs for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. The use of a surrogate endpoint can considerably shorten the time to approval, allowing more rapid patient access to promising new treatments for serious or life-threatening diseases. Accelerated Approval is given on the condition that post-marketing clinical trials verify the anticipated clinical benefit. Over 80 new critical products have been approved under Accelerated Approval since the program was established, including nearly 30 drugs to treat cancer. Three of the 30 new molecular entities (NMEs) approved in 2011 were approved under Accelerated Approval. NMEs represent the truly innovative new medicines.

Once a drug receives Fast Track designation, early and frequent communications between FDA and a drug company are encouraged throughout the entire drug development and review process. The frequency of communications ensures that questions and issues are resolved quickly, often leading to earlier drug approval and access by patients.

FDA also recognizes circumstances in which there is public health value in making products available prior to marketing approval. A promising but not yet fully evaluated treatment may sometimes represent the best choice for individuals with serious or life-threatening diseases, who lack a satisfactory therapy.

FDA allows for access to investigational products through multiple mechanisms. Clinical trials are the best mechanism for a patient to receive an investigational drug, because they provide a range of patient protections and benefits and they maximize the gathering of useful information about the product, which benefits the entire patient population. However, there are times when an individual cannot enroll in a clinical trial. In some cases, the patient may gain access to an investigational therapy through one of the alternative mechanisms, and FDA’s Office of Special Health Issues assists patients and their doctors in this endeavor.

Challenges for the Current Drug Program

Although we can report many important successes with the current program, new challenges have also emerged that offer an opportunity for further enhancement. While new authorities from the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA) have strengthened drug safety, they have put strains on FDA’s ability to meet premarket review performance goals and address post-market review activities. In addition, there has been a significant increase in the number of foreign sites included in clinical trials to test drug safety and effectiveness, and an increase in the number of foreign facilities used in manufacturing new drugs for the U.S. market. While foreign sites can play an important role in enabling access to new drugs, the need to travel much farther to conduct pre-approval inspections for clinical trials and manufacturing sites overseas has created additional challenges for completion of FDA’s review within the existing PDUFA review performance goals, while at the same time trying to communicate with sponsors to see if identified issues can be resolved before the review performance goal date.

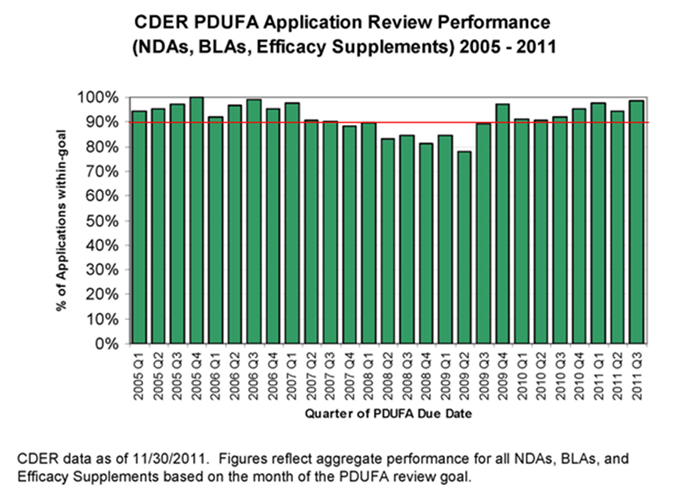

Despite these challenges, FDA has maintained strong performance in meeting the PDUFA application review goals, with the exception of a dip in FY 2008-09, when staff resources were shifted within the discretion afforded FDA to ensure timely implementation of all of the new FDAAA provisions that affected activities in the new drug review process. Recent performance data show that FDA has returned to meeting or exceeding goals for review of marketing applications under PDUFA. This is shown in Figure 3.

However, FDA wants to meet not only the letter, but also the spirit of the PDUFA program. That is, we want to speed patient access to drugs shown to be safe and effective for the indicated uses while also meeting our PDUFA goals.

The NDA/BLA approval phase of drug development is reported to have the highest success rate of any phase of drug development. That is, the percentage of drugs that fail after the sponsor submits an NDA/BLA to FDA is less than the percentages that fail in preclinical development, and each phase of clinical development. At the same time, it is critical to our public health mission that we work with industry and other stakeholders to take steps to reduce uncertainty and increase the success of all phases of drug development. We must leverage advances in science and technology to make sure that we have the knowledge and tools we need to rapidly and meaningfully evaluate medical products. The science of developing new tools, standards, and approaches to assess the safety, efficacy, quality, and performance of FDA-regulated products—known as regulatory science—is about more than just speeding drug development prior to the point at which FDA receives an application for review and approval. It also gives us the scientific tools to modernize and streamline our regulatory process. With so much at stake for public health, FDA has made advances in regulatory science a top priority. The Agency is both supporting mission-critical science at FDA and exploring a range of new partnerships with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and academic institutions to develop the science needed to maximize advances in biomedical research and bring the development and assessment of promising new therapies and devices into the 21st century. With this effort, FDA is poised to support a wave of innovation to transform medicine and save lives.

For example, FDA is working to improve the science behind certain clinical trial designs. Recent advances in two clinical trial designs—called non-inferiority and adaptive designs—have required FDA to conduct more complex reviews of clinical trial protocols and new marketing applications. Improving the scientific bases of these trial designs should add efficiency to the drug review process, encourage the development of novel products, and speed new therapies to patients.

FDA has also taken steps to help facilitate the development and approval of safe and effective drugs for Americans with rare diseases. Therapies for rare diseases—those affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the United States—represent the most rapidly expanding area of drug development. Although each disease affects a relatively small population, collectively, rare diseases affect about 25 million Americans. Approximately one-third of the NMEs and new biological products approved in the last five years have been drugs for rare diseases. Because of the small numbers of patients who suffer from each disease, FDA often allows non-traditional approaches to establishing safety and effectiveness. For example, FDA approved Voraxaze (glucarpidase) in January 2012 to treat patients with toxic methotrexate levels in their blood due to kidney failure, which affects a small population of patients each year. Methotrexate is a commonly used cancer chemotherapy drug normally eliminated from the body by the kidneys. Patients receiving high doses of methotrexate may develop kidney failure. Voraxaze was approved based on data in 22 patients from a single clinical trial, which showed decreased levels of methotrexate in the blood. Prior to the approval of Voraxaze, there were no effective therapies for the treatment of toxic methotrexate levels in patients with renal failure.

Just yesterday, January 31, 2012, FDA approved Kalydeco (ivacaftor) to treat patients age 6 or older with Cystic Fibrosis (CF) and who have a specific genetic defect (G551D mutation). CF occurs in approximately 30,000 children and adults in the United States. The G551D mutation occurs in approximately 4 percent of patients with CF, totaling approximately 1,200 patients in the United States. CF is a serious inherited disease that affects the lungs and other organs in the body, leading to breathing and digestive problems, trouble gaining weight, and other problems. There is no cure for CF, and despite progress in the treatment of the disease, most patients with CF have shortened life spans and do not live beyond their mid-30’s. Ivacaftor was given a Priority Review by FDA. Due to the results of these studies showing a significant benefit to patients with CF with the G551D mutation, ivacaftor was reviewed and approved by FDA in approximately half of the six-month Priority Review period. Ivacaftor will be the first medicine that targets the underlying cause of CF; currently, therapy is aimed at treating symptoms or complications of the disease.

PDUFA Reauthorization

In PDUFA IV, Congress directed FDA to take additional steps to ensure that public stakeholders, including consumer, patient, and health care professional organizations, would have adequate opportunity to provide input to the reauthorization and any program enhancements for PDUFA V. Congress directed the Agency to hold an initial public meeting and then to meet with public stakeholders periodically, while conducting negotiations with industry to hear their views on the reauthorization and their suggestions for changes to the PDUFA performance goals. PDUFA IV also required that minutes from negotiation sessions held with industry be made public.

Based on a public meeting held in April 2010, input from a public docket, and the Agency’s own internal analyses of program challenge areas, FDA developed a set of potential proposed enhancements for PDUFA V and in July 2010, began negotiations with industry and parallel discussions with public stakeholders. These discussions concluded in May 2011 and we held a public meeting on October 24, 2011, where we solicited comments on the proposed recommendations. We also opened a public docket for comments. We considered these comments, and on January 13, 2012, we transmitted the final recommendations to Congress.

We are very pleased to report that the enhancements for PDUFA V address many of the top priorities identified by public stakeholders, the top concerns identified by industry, and the most important challenges identified within FDA. I will briefly summarize these enhancements.

A. Review Program for New Drug Applications, New Molecular Entities, and Original Biologics License Applications

FDA’s existing review performance goals for priority and standard applications—six and 10 months respectively—were established in 1997. Since that time, additional requirements in the drug review process have made those goals increasingly challenging to meet, particularly for more complex applications like new molecular entity (NME) NDAs and original BLAs. FDA also recognizes that increasing communication between the Agency and sponsors during the application review has the potential to increase efficiency in the review process.

To address the desire for increased communication and greater efficiency in the review process, we agreed to an enhancement to FDA’s review program for NME NDAs and original BLAs in PDUFA V. This program includes pre-submission meetings, mid-cycle communications, and late-cycle meetings between FDA and sponsors for these applications. To accommodate this increased interaction during regulatory review, as agreed to with industry, FDA’s review clock would begin after the 60-day administrative filing review period for this subset of applications. The impact of these modifications on the efficiency of drug review for this subset of applications will be assessed during PDUFA V.

B. Enhancing Regulatory Science and Expediting Drug Development

The following five enhancements focus on regulatory science and expediting drug development.

1. Promoting Innovation Through Enhanced Communication Between FDA and Sponsors During Drug Development

FDA recognizes that timely interactive communication with sponsors can help foster efficient and effective drug development. In some cases, a sponsor’s questions may be complex enough to require a formal meeting with FDA, but in other instances, a question may be relatively straightforward such that a response can be provided more quickly. However, our review staff’s workload and other competing public health priorities can make it challenging to develop an Agency response to matters outside of the formal meeting process.

This enhancement involves a dedicated drug development communication and training staff, focused on improving communication between FDA and sponsors during development. This staff will be responsible for identifying best practices for communication between the Agency and sponsors, training review staff, and disseminating best practices through published guidance.

2. Methods for Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis typically attempts to combine the data or findings from multiple completed studies to explore drug benefits and risks and, in some cases, uncover what might be a potential safety signal in a premarket or post-market context. However, there is no consensus on best practices in conducting a meta-analysis. With the growing availability of clinical trial data, an increasing number of meta-analyses are being conducted based on varying sets of data and assumptions. If such studies conducted outside FDA find a potential safety signal, FDA will work to try to confirm—or correct—the information about a potential harm. To do this, FDA must work quickly to conduct its own meta-analyses to include publicly available data and the raw clinical trial data submitted by drug sponsors that would typically not be available to outside researchers. This is resource-intensive work and often exceeds the Agency’s on-board scientific and computational capacity, causing delays in FDA findings that prolong public uncertainty.

PDUFA V enhancements include the development of a dedicated staff to evaluate best practices and limitations in meta-analysis methods. Through a rigorous public comment process, FDA would develop guidance on best practices and the Agency’s approach to meta-analysis in regulatory review and decision-making.

3. Biomarkers and Pharmacogenomics

Pharmacogenomics and the application of qualified biomarkers have the potential to decrease drug development time by helping to demonstrate benefits, establish unmet medical needs, and identify patients who are predisposed to adverse events. FDA provides regulatory advice on the use of biomarkers to facilitate the assessment of human safety in early phase clinical studies, to support claims of efficacy, and to establish the optimal dose selection for pivotal efficacy studies. This is an area of new science where the Agency has seen a marked increase in sponsor submissions to FDA. In the 2008-2010 period, the Agency experienced a nearly four-fold increase in this type of review work.

PDUFA V enhancements include augmenting the Agency’s clinical, clinical pharmacology, and statistical capacity to adequately address submissions that propose to utilize biomarkers or pharmacogenomic markers. The Agency would also hold a public meeting to discuss potential strategies to facilitate scientific exchanges on biomarker issues between FDA and drug manufacturers.

4. Use of Patient-reported Outcomes

Assessments of study endpoints known as patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are increasingly an important part of successful drug development. PROs measure treatment benefit or risk in medical product clinical trials from the patients’ point of view. They are critical in understanding drug benefits and harm from the patients’ perspective. However, PROs require rigorous evaluation and statistical design and analysis to ensure reliability to support claims of clinical benefit. Early consultation between FDA and drug sponsors can ensure that endpoints are well-defined and reliable. However, the Agency does not have the capacity to meet the current demand from industry.

PDUFA V enhancements include an initiative to improve FDA’s clinical and statistical capacity to address submissions involving PROs and other endpoint assessment tools, including providing consultation during the early stages of drug development. In addition, FDA will convene a public meeting to discuss standards for PRO qualification, new theories in endpoint measurement, and the implications for multi-national trials.

5. Development of Drugs for Rare Diseases

FDA’s oversight of rare disease drug development is complex and resource intensive. Rare diseases are a highly diverse collection of disorders, their natural histories are often not well-described, only small population sizes are often available for study, and they do not usually have well-defined outcome measures. This makes the design, execution, and interpretation of clinical trials for rare diseases difficult and time consuming, requiring frequent interaction between FDA and drug sponsors. If recent trends in orphan designations are any indication, FDA can expect an increase in investigational activity and marketing applications for orphan products in the future.

Another PDUFA V enhancement includes FDA facilitation of rare disease drug development by issuing relevant guidance, increasing the Agency’s outreach efforts to the rare disease patient community, and providing specialized training in rare disease drug development for sponsors and FDA staff.

C. Enhancing Benefit-Risk Assessment

FDA has been developing an enhanced, structured approach to benefit-risk assessments that accurately and concisely describes the benefit and risk considerations in the Agency’s drug regulatory decision-making. Part of FDA’s decision-making lies in thinking about the context of the decision—an understanding of the condition treated and the unmet medical need. Patients who live with a disease have a direct stake in the outcome of drug review. The FDA drug review process could benefit from a more systematic and expansive approach to obtaining the patient perspective on disease severity and the potential gaps or limitations in available treatments in a therapeutic area.

PDUFA V enhancements include expanded implementation of FDA’s benefit-risk framework in the drug review process, including holding public workshops to discuss the application of frameworks for considering benefits and risks that are most appropriate for the regulatory setting. FDA would also conduct a series of public meetings between its review divisions and the relevant patient advocacy communities to review the medical products available for specific indications or disease states that will be chosen through a public process.

D. Enhancement and Modernization of the FDA Drug Safety System

The enhancements for PDUFA V include two post-market, safety-focused initiatives.

1. Standardizing Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies

FDAAA gave FDA authority to require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) when FDA finds that a REMS is necessary to ensure that the benefits of a drug outweigh its risks. Some REMS are more restrictive types of risk management programs that include elements to assure safe use (ETASU). These programs can require such tools as prescriber training or certification, pharmacy training or certification, dispensing in certain health care settings, documentation of safe use conditions, required patient monitoring, or patient registries. ETASU REMS can be challenging to implement and evaluate, involving cooperation of all segments of the health care system. Our experience with REMS to date suggests that the development of multiple individual programs has the potential to create burdens on the health care system and, in some cases, could limit appropriate patient access to important therapies.

PDUFA V enhancements initiate a public process to explore strategies and initiate projects to standardize REMS with the goal of reducing burden on practitioners, patients, and others in the health care setting. Additionally, FDA will conduct public workshops and develop guidance on methods for assessing the effectiveness of REMS and the impact on patient access and burden on the health care system.

2. Using the Sentinel Initiative to Evaluate Drug Safety Issues

FDA’s Sentinel Initiative is a long-term program designed to build and implement a national electronic system for monitoring the safety of FDA-approved medical products. FDAAA required FDA to collaborate with federal, academic, and private entities to develop methods to obtain access to disparate data sources and validated means to link and analyze safety data to monitor the safety of drugs after they reach the market, an activity also known as “active post-market drug safety surveillance.” FDA will use user fee funds to conduct a series of activities to determine the feasibility of using Sentinel to evaluate drug safety issues that may require regulatory action, e.g., labeling changes, post-marketing requirements, or post-marketing commitments. This may shorten the time it takes to better understand new or emerging drug safety issues. PDUFA V enhancements will enable FDA to initiate a series of projects to establish the use of active post-market drug safety surveillance in evaluating post-market safety signals in population-based databases. By leveraging public and private health care data sources to quickly evaluate drug safety issues, this work may reduce the Agency’s reliance on required post-marketing studies and clinical trials.

E. Required Electronic Submissions and Standardization of Electronic Application Data

The predictability of the FDA review process relies heavily on the quality of sponsor submissions. The Agency currently receives submissions of original applications and supplements in formats ranging from paper-only to electronic-only, as well as hybrids of the two media. The variability and unpredictability of submitted formats and clinical data layout present major obstacles to conducting a timely, efficient, and rigorous review within current

PDUFA goal time frames. A lack of standardized data also limits FDA’s ability to transition to more standardized approaches to benefit-risk assessment and impedes conduct of safety analyses that inform FDA decisions related to REMS and other post-marketing requirements.

PDUFA V enhancements include a phased-in requirement for standardized, fully electronic submissions during PDUFA V for all marketing and investigational applications. Through partnership with open standards development organizations, the Agency would also conduct a public process to develop standardized terminology for clinical and non-clinical data submitted in marketing and investigational applications.

F. User Fee Increase for PDUFA V

The cost of the agreed upon PDUFA V enhancements translates to an overall increase in fees of approximately six percent.

G. PDUFA V Enhancements for a Modified Inflation Adjuster and Additional Evaluations of the Workload Adjuster

In calculating user fees for each new fiscal year, FDA adjusts the base revenue amount by inflation and workload as specified in the statute. PDUFA V enhancements include a modification to the inflation adjuster to accurately account for changes in its costs related to payroll compensation and benefits as well as changes in non-payroll costs. In addition, FDA will continue evaluating the workload adjuster that was developed during the PDUFA IV negotiations to ensure that it continues to adequately capture changes in FDA’s workload.

Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act /Pediatric Research Equity Act

Background

The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA), enacted in 1997 as part of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA) and reauthorized in 2002 and 2007, provides incentives to manufacturers who voluntarily conduct studies of drugs in children. This law provides six months of additional exclusivity for a drug (active moiety), in return for conducting pediatric studies in response to a written request (WR) issued by FDA. To qualify for pediatric exclusivity, the pediatric studies must “fairly respond” to a WR issued by FDA that describes the needed pediatric studies (including, for example, indications to be studied or number of patients). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Affordable Care Act) extended availability of pediatric exclusivity to biological products but, due to the recent nature of this change, no biological product has received pediatric exclusivity to date.

The Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA), enacted in 2003, works in concert with BPCA. PREA provides FDA the authority to require pediatric studies under certain conditions. PREA requires pediatric assessments of drugs and biological products for the same indications previously approved or pending approval, when the sponsor submits an application or supplemental application to FDA for a new indication, new dosing regimen, new active ingredient, new dosage form, or new route of administration.

Both BPCA and PREA expire September 30, 2012, if not reauthorized.

Need for Pediatric Information

Before enactment of BPCA in 1997, approximately 80 percent of medication labels in the Physician’s Desk Reference did not have pediatric-use information—data to establish the correct dose for pediatric patients or confirm safety or efficacy in the pediatric population. All too often health care professionals were forced to rely on imprecise and ineffective methods to provide medications for children, such as adjusting dosing based on weight or crushing pills and mixing them in food. Pediatric patients are subject to many of the same diseases as adults and are, by necessity, often treated with the same drugs and biological products as adults. Inadequate dosing information may expose pediatric patients to overdosing or underdosing. Overdosing may increase the risk of adverse reactions that could be avoided with an appropriate pediatric dose; underdosing may lead to ineffective treatment. The lack of pediatric-specific safety information in product labeling also means caretakers and health care professionals are unable to monitor for and manage pediatric-specific adverse events. In situations where younger pediatric populations cannot take the adult formulation of a product, the failure to develop a pediatric formulation that can be used by young children (e.g., a liquid or chewable tablet) also can deny children access to important medications.

Success of BPCA and PREA

Together, BPCA and PREA have generated pediatric studies on many drugs and helped to provide important new safety, effectiveness, and dosing information for drugs used in children. Both statutes continue to foster an environment that promotes pediatric studies and to build an infrastructure for pediatric trials that was previously non-existent.

Over the past 15 years, approximately 400 drugs have been studied and labeled for pediatric use under these two laws. Since 1997, BPCA, the exclusivity incentive program, has generated labeling changes for 250 products. The labeling for 120 products has been updated to include new information, expanding use of the product to a broader pediatric population; the labeling of 29 products had specific dosing adjustments; the labeling of 69 products was changed to show that the products were found not to be safe and effective for children; and 55 products had new or enhanced pediatric safety information added to the labeling.[4]

Since PREA was enacted, FDA has approved approximately 1,450 NDAs and supplemental NDAs that fell within the scope of PREA (i.e., applications for new active ingredients, new dosage forms, new indications, new routes of administration, or new dosing regimens). These approvals have resulted in approximately 231 labeling changes involving pediatric studies linked to PREA assessments. In addition, FDA has approved approximately 105 BLAs and supplemental BLAs that fell within the scope of PREA.

Examples of New Pediatric Information Generated by BPCA and PREA

Migraine headaches – Axert (almotriptan) was studied and labeled for age 12 years and older. Before enactment of BPCA and PREA, no medications were studied and labeled for migraines in children.

Diabetes – Apidra (insulin gluilsine recombinant) has been studied and labeled down to age 4 for Type 1 diabetes.

Arthritis – Actemra (tocilizumab) has been studied and labeled down to age 2 for Active Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (SJIA).

Pain – Ofirmev/acetaminophen injection has been studied and labeled down to age 2 for mild-to-moderate pain/moderate-to-severe pain with adjunctive opioid analgesics and reduction of fever.

Brain Tumors – Afinitor (everolimus) has been studied and labeled down to age 3 for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) associated with tuberous sclerosis (TS).

BPCA and PREA require review of adverse event reports on a regular basis. To date, adverse event reviews have been presented to the Pediatric Advisory Committee (PAC) for 129 products. In addition, as directed by BPCA, FDA has worked with NIH and the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) to facilitate the study of off-patent drugs not eligible for exclusivity under BPCA.

Despite the successes of these two programs, there is more work to be done. There is still a large number of drug and biological products that are inadequately labeled for children. More broadly, long-term safety and effects on growth, learning, and behavior are critically important to the safe use of certain medications and continue to be understudied. Due to technical challenges and the need for sequential studies, slow but deliberate progress is being made studying the safety and efficacy of approved therapies used to treat neonates (age birth to one month). These issues are still of concern, as it is this youngest population that is undergoing marked physiologic and developmental changes, which are affected by drug therapies.

FDA welcomes the opportunity to work with Congress to ensure that the benefits of an incentive program can continue, in conjunction with FDA’s authority to require mandatory studies, as Congress considers the reauthorization of the BPCA and PREA programs.

Challenges Posed by Globalization

In addition to reauthorizing PDUFA, FDA is also committed to meeting challenges posed by increased globalization. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt established the modern FDA in 1938, the percentage of food and medical products imported into the United States was minimal. Today, approximately 40 percent of the drugs Americans take are manufactured outside our borders, and up to 80 percent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients in those drugs comes from foreign sources. In July 2011, FDA published a special report, “Pathway to Global Product Safety and Quality,” our global strategy and action plan that will allow us to more effectively oversee the safety of all products that reach U.S. consumers in the future. As detailed in the plan, over the next decade, FDA will focus on strengthened collaboration, improved information sharing and gathering, data-driven risk analytics, and the smart allocation of resources through partnerships with counterpart regulatory agencies, other government entities, international organizations, and other key stakeholders, including industry.

Toward this goal, I created a directorate in July 2012, focused on grappling with the truly global nature of today’s food and drug production and supply. I appointed a Deputy Commissioner for Global Regulatory Operations and Policy to provide broad direction and support to FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs and Office of International Programs, with a mandate from me to make response to the challenges of globalization and import safety a top priority in the years to come and to ensure that we fully integrate our domestic and international programs to best promote and protect the health of the public.

CONCLUSION

PDUFA IV expires on September 30, 2012, and FDA is ready to work with you to ensure timely reauthorization of this critical program. If we are to sustain and build on our record of accomplishments, it is critical that the reauthorization occur seamlessly without any gap between the expiration of the old law and the enactment of PDUFA V.

Thank you for your contributions to the continued success of PDUFA and to the mission of FDA. I am happy to answer questions you may have.

Last revised: February 23, 2012