Photo: Stockbyte

As we enter the sneezing season, outdoor allergies are on the rise for many Americans. The cost to our healthcare system from all allergies—indoor and outdoor—is becoming truly breathtaking.

If you are one of the 18.2 million Americans who suffer from allergic rhinitis, or "hay fever," chances are you may be sneezing, reaching for a box of tissues or rubbing your itchy, red, watery eyes as you read this. It's May and the start of yet another allergy season, when pollen seems to cover the universe and very little relief is in sight.

While many of us endure mild to moderate symptoms, the larger truth is that the world of allergies is a complex and costly landscape. More than 50 million Americans suffer from all forms of allergies, which are the sixth-leading cause of chronic diseases in the United States. In 1996, hay fever alone accounted for nearly 14 million doctor visits and cost the healthcare system approximately $1.9 billion. For unknown reasons, the incidence of hay fever has risen substantially in the past 15 years.

These are just a few of the reasons why the NIH's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) is committed to funding ongoing research for new ways to manage and, perhaps, even prevent allergic diseases. In 2005, NIAID awarded more than $116 million in grants and contracts for investigation into the mechanisms, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of allergic diseases, including asthma and allergic rhinitis.

For more than 50 years, NIAID research has led to new diagnostic tests, vaccines, therapies and technologies that have improved the health of millions of people in the United States and around the world. One such NIAID-funded study has shown recently that an environmental intervention program to reduce indoor allergens, especially from cockroach and dust mites, in the homes of inner-city children with moderate to severe asthma is quite effective in reducing allergen levels and asthma symptoms. Since continued exposure to allergens induces asthma's symptoms, avoiding them is an attractive approach, according to Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., NIAID Director. "The NIAID-sponsored Inner City Asthma Study in children demonstrates that environmental interventions reduce wheezing in proportion to the reduction in allergens," he says. (Read more comments from Dr. Fauci on page 23.) Information on this and other NIHfunded allergy studies, as well as a host of other resources on allergies of all kinds, is available at www.medlineplus.gov.

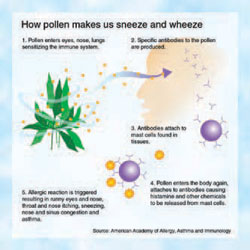

How pollen makes us sneeze and wheeze

1. Pollen enters eyes, nose, lungs sensitizing the immune system.

2. Specific antibodies to the pollen are produced.

3. Antibodies attach to mast cells found in tissues.

4. Pollen enters the body again, attaches to antibodies causing histamine and other chemicals to be released from mast cells

5. Allergic reaction is triggered resulting in runny eyes and nose, throat and nose itching, sneezing, nose and sinus congestion and asthma.

Source: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Nuisance or Health Threat?

For most people, hay fever is a seasonal nuisance—something to endure for a few weeks once or twice a year. But for others, such allergies can be life-altering conditions that lead to more serious complications, including sinusitis and asthma.

- Sinusitis, one of the most commonly reported chronic diseases, is the inflammation or infection of the paranasal sinuses, which are four pairs of cavities located within the skull. Congestion here can lead to pressure and pain over the eyes, around the nose or in the cheeks just above the teeth. Chronic sinusitis is associated with persistent inflammation and is often difficult to treat. Extended bouts of hay fever, for instance, can increase the likelihood of development of chronic sinusitis.The annual cost of managing sinusitis has been estimated as high as $5.8 billion.

- Asthma is a disease of the lungs in which the primary symptom is a narrowing or blockage of the airways, resulting in wheezing, shortness of breath, coughing and other breathing difficulties. Asthma attacks can be triggered by viral infection, cold air, exercise, anxiety, allergens and other factors. Allergic asthma is responsible for almost 80 percent of all asthma diagnoses. It presents the same symptoms as nonallergic asthma, but differs in that it is set off primarily by an immune response to specific allergens.

Both sinusitis and allergic asthma are manageable, but the research challenge always is to go beyond controlling the symptoms to address the root causes of disease.

Defending Against Invaders

In a normal immune system, invading bacteria and viruses trigger antibodies, which are "programmed" to remember and defend against these germs in the future. During an allergic reaction, however, the immune system treats generally harmless allergens, such as pollen, mold, animal dander or dust mites, as pathogens and begins producing large amounts of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies.

Allergic reactions are the biological equivalent of a fire drill: The body defends itself against a potential pathogen although none is present. The process is repeated as long as the immune system detects the allergen. Some allergy sufferers are genetically disposed to have a sensitive immune system. In addition, the severity of allergy symptoms can become worse due to illness or pregnancy.

That is what happened to Amy Kindt, a Mt. Clemens, Michigan, mother of two, who always suffered from hay fever when pollen counts rose during the spring and fall. However, since she became pregnant with her first child in 2000, the frequency of her symptoms has gone way up.

"Ever since my first pregnancy, it seems I'm allergic to something all day, every day," she says. "I cough a lot from the drainage, and it makes it hard to sleep. Over-the-counter medications don't seem to work any more."

MedlinePlus.gov Resources

Want to know more about allergic rhinitis? Check out the resources at www.medlineplus.gov. Do a search on "allergy" or use one of the following quick links:

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: http://www3.niaid.nih.gov

Airborne Allergens: http://www.niaid.nih.gov/

publications/allergens/

airborne_allergens.pdf

Allergy Clinical Trials: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/

gui/action/FindCondition?ui=

D006967&recruiting=true

Asthma and Allergy Resources:

http://www.niaid.nih.gov/factsheets/

allergyr.htm

Useful Publications

Fact sheets, symptom checklists, prevention tips and more are at http://www.niaid.nih.gov/

publications/allergies.htm

Testing for Allergies

When it comes to allergies, knowledge is power. Knowing exactly what you are allergic to can help determine the best way to lessen or prevent exposure and treat reactions when they occur. There are several tests that physicians use to pinpoint what you are allergic to. For example:

- Allergy skin test—The most commonly used allergy skin test, known as a "prick test," this diagnostic procedure involves pricking your skin with the extract of a specific allergen, then observing the skin's reaction. Another test, the intradermal injection, introduces allergens just below the skin's outer layers, is more sensitive than the prick test and is sometimes used when the prick test produces negative results. Allergy skin testing is considered the most sensitive testing method and provides rapid results. However, skin tests cannot be used when a patient suffers from certain skin conditions, such as eczema.

- RadioAllergoSorbent Test (RAST) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent blood tests— The RAST and enzyme-linked immunosorbent tests are two blood tests that provide information similar to allergy skin testing, namely the levels of allergic (IgE) antibodies to allergens.

Searching for Relief

For allergy sufferers, the best treatment is to avoid the offending allergens altogether. This may be possible if the irritant is a specific food, like peanuts, which can be cut out of the diet, but not when the very air we breathe is loaded with allergens. For example, a single ragweed plant can produce a million grains of pollen a day, and ragweed pollen has been found 400 miles out at sea and two miles high in the atmosphere.

Air purifiers, filters, humidifiers and conditioners provide varying degrees of relief, but none is 100 percent effective. Normally, allergy sufferers look to various over-the-counter medications and physician-prescribed therapies. (See sidebar story, "Finding Relief from Allergy's Grip," page 21.)

Hoping for a Cure

Relief may someday come in the form of an allergy vaccine, several of which are in development and show great promise. In one clinical trial, for instance, a series of six injections of a newly developed and specially formulated ragweed vaccine lessened symptoms and reduced the need for antihistamines among study participants. Perhaps more exciting is the fact that this particular vaccine seems to provide benefits for at least one additional year, without the need for booster shots.

For vaccines to be most effective, they must be specific. For someone allergic to ragweed, the new vaccine in development may be good news, but not to one who reacts only to grass pollen. Clearly, more research, development and testing are in order. While effective allergy vaccines are still years away from general release, research funded by NIH shows long-term promise.