Biliary Atresia

On this page:

- What is biliary atresia?

- Who is at risk for biliary atresia?

- What are the symptoms of biliary atresia?

- What causes biliary atresia?

- How is biliary atresia diagnosed?

- How is biliary atresia treated?

- What are possible complications after the Kasai procedure?

- What medical care is needed after a liver transplant?

- Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

- Points to Remember

- Hope through Research

- For More Information

- Acknowledgments

What is biliary atresia?

Biliary atresia is a life-threatening condition in infants in which the bile ducts inside or outside the liver do not have normal openings.

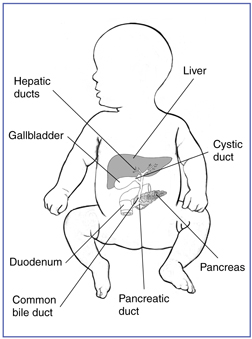

Bile ducts in the liver, also called hepatic ducts, are tubes that carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder for storage and to the small intestine for use in digestion. Bile is a fluid made by the liver that serves two main functions: carrying toxins and waste products out of the body and helping the body digest fats and absorb the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

Normal liver and biliary system

With biliary atresia, bile becomes trapped, builds up, and damages the liver. The damage leads to scarring, loss of liver tissue, and cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is a chronic, or long lasting, liver condition caused by scar tissue and cell damage that makes it hard for the liver to remove toxins from the blood. These toxins build up in the blood and the liver slowly deteriorates and malfunctions. Without treatment, the liver eventually fails and the infant needs a liver transplant to stay alive.

The two types of biliary atresia are fetal and perinatal. Fetal biliary atresia appears while the baby is in the womb. Perinatal biliary atresia is much more common and does not become evident until 2 to 4 weeks after birth. Some infants, particularly those with the fetal form, also have birth defects in the heart, spleen, or intestines.

[Top]

Who is at risk for biliary atresia?

Biliary atresia is rare and only affects about one out of every 18,000 infants.1 The disease is more common in females, premature babies, and children of Asian or African American heritage.

1Prevelance of rare diseases: Bibliographic data. Orphareport Series, Rare Diseases Collection website. www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_decreasing_prevalence_or_cases.pdf ![]() . Published November 2011. Accessed March 23, 2012.

. Published November 2011. Accessed March 23, 2012.

[Top]

What are the symptoms of biliary atresia?

The first symptom of biliary atresia is jaundice––when the skin and whites of the eyes turn yellow. Jaundice occurs when the liver does not remove bilirubin, a reddish-yellow substance formed when hemoglobin breaks down. Hemoglobin is an iron-rich protein that gives blood its red color. Bilirubin is absorbed by the liver, processed, and released into bile. Blockage of the bile ducts forces bilirubin to build up in the blood.

Other common symptoms of biliary atresia include

- dark urine, from the high levels of bilirubin in the blood spilling over into the urine

- gray or white stools, from a lack of bilirubin reaching the intestines

- slow weight gain and growth

[Top]

What causes biliary atresia?

Biliary atresia likely has multiple causes, though none are yet proven. Biliary atresia is not an inherited disease, meaning it does not pass from parent to child. Therefore, survivors of biliary atresia are not at risk for passing the disorder to their children.

Biliary atresia is most likely caused by an event in the womb or around the time of birth. Possible triggers of the event may include one or more of the following:

- a viral or bacterial infection after birth, such as cytomegalovirus, reovirus, or rotavirus

- an immune system problem, such as when the immune system attacks the liver or bile ducts for unknown reasons

- a genetic mutation, which is a permanent change in a gene’s structure

- a problem during liver and bile duct development in the womb

- exposure to toxic substances

[Top]

How is biliary atresia diagnosed?

No single test can definitively diagnose biliary atresia, so a series of tests is needed. All infants who still have jaundice 2 to 3 weeks after birth, or who have gray or white stools after 2 weeks of birth, should be checked for liver damage.2

Infants with suspected liver damage are usually referred to a

- pediatric gastroenterologist, a doctor who specializes in children’s digestive diseases

- pediatric hepatologist, a doctor who specializes in children’s liver diseases

- pediatric surgeon, a doctor who specializes in operating on children’s livers and bile ducts

The health care provider may order some or all of the following tests to diagnose biliary atresia and rule out other causes of liver problems. If biliary atresia is still suspected after testing, the next step is diagnostic surgery for confirmation.

2Hartley JL, Davenport M, Kelly DA. Biliary atresia. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1704–1713.

Blood test. A blood test involves drawing blood at a health care provider’s office or commercial facility and sending the sample to a lab for analysis. High levels of bilirubin in the blood can indicate blocked bile ducts.

Abdominal x rays. An x ray is a picture created by using radiation and recorded on film or on a computer. The amount of radiation used is small. An x ray is performed at a hospital or outpatient center by an x-ray technician, and the images are interpreted by a radiologist—a doctor who specializes in medical imaging. Anesthesia is not needed, but sedation may be used to keep infants still. The infant will lie on a table during the x ray. The x-ray machine is positioned over the abdominal area. Abdominal x rays are used to check for an enlarged liver and spleen.

Ultrasound. Ultrasound uses a device, called a transducer, that bounces safe, painless sound waves off organs to create an image of their structure. The procedure is performed in a health care provider’s office, outpatient center, or hospital by a specially trained technician, and the images are interpreted a radiologist. Anesthesia is not needed, but sedation may be used to keep the infant still. The images can show whether the liver or bile ducts are enlarged and whether tumors or cysts are blocking the flow of bile. An ultrasound cannot be used to diagnose biliary atresia, but it does help rule out other common causes of jaundice.

Liver scans. Liver scans are special x rays that use chemicals to create an image of the liver and bile ducts. Liver scans are performed at a hospital or outpatient facility, usually by a nuclear medicine technician. The infant will usually receive general anesthesia or be sedated before the procedure. Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scanning, a type of liver scan, uses injected radioactive dye to trace the path of bile in the body. The test can show if and where bile flow is blocked. Blockage is likely to be caused by biliary atresia.

Liver biopsy. A biopsy is a procedure that involves taking a piece of liver tissue for examination with a microscope. The biopsy is performed by a health care provider in a hospital with light sedation and local anesthetic. The health care provider uses imaging techniques such as ultrasound or a computerized tomography scan to guide the biopsy needle into the liver. The liver tissue is examined in a lab by a pathologist—a doctor who specializes in diagnosing diseases. A liver biopsy can show whether biliary atresia is likely. A biopsy can also help rule out other liver problems, such as hepatitis—an irritation of the liver that sometimes causes permanent damage.

Diagnostic surgery. During diagnostic surgery, a pediatric surgeon makes an incision, or cut, in the abdomen to directly examine the liver and bile ducts. If the surgeon confirms that biliary atresia is the problem, a Kasai procedure will usually be performed immediately. Diagnostic surgery and the Kasai procedure are performed at a hospital or outpatient facility; the infant will be under general anesthesia during surgery.

[Top]

How is biliary atresia treated?

Biliary atresia is treated with surgery, called the Kasai procedure, or a liver transplant.

Kasai Procedure

The Kasai procedure, named after the surgeon who invented the operation, is usually the first treatment for biliary atresia. During a Kasai procedure, the pediatric surgeon removes the infant’s damaged bile ducts and brings up a loop of intestine to replace them. As a result, bile flows straight to the small intestine.

While this operation doesn’t cure biliary atresia, it can restore bile flow and correct many problems caused by biliary atresia. Without surgery, infants with biliary atresia are unlikely to live past age 2. This procedure is most effective in infants younger than 3 months old, because they usually haven’t yet developed permanent liver damage. Some infants with biliary atresia who undergo a successful Kasai procedure regain good health and no longer have jaundice or major liver problems.

The Kasai procedure

If the Kasai procedure is not successful, infants usually need a liver transplant within 1 to 2 years. Even after a successful surgery, most infants with biliary atresia slowly develop cirrhosis over the years and require a liver transplant by adulthood.

Liver Transplant

Liver transplantation is the definitive treatment for biliary atresia, and the survival rate after surgery has increased dramatically in recent years. As a result, most infants with biliary atresia now survive. Progress in transplant surgery has also increased the availability and efficient use of livers for transplantation in children, so almost all infants requiring a transplant can receive one.

In years past, the size of the transplanted liver had to match the size of the infant’s liver. Thus, only livers from recently deceased small children could be transplanted into infants with biliary atresia. New methods now make it possible to transplant a portion of a deceased adult’s liver into an infant. This type of surgery is called a reduced-size or split-liver transplant.

Part of a living adult donor’s liver can also be used for transplantation. Healthy liver tissue grows quickly; therefore, if an infant receives part of a liver from a living donor, both the donor and the infant can grow complete livers over time.

Infants with fetal biliary atresia are more likely to need a liver transplant—and usually sooner—than infants with the more common perinatal form. The extent of damage can also influence how soon an infant will need a liver transplant.

[Top]

What are possible complications after the Kasai procedure?

After the Kasai procedure, some infants continue to have liver problems and, even with the return of bile flow, some infants develop cirrhosis. Possible complications after the Kasai procedure include ascites, bacterial cholangitis, portal hypertension, and pruritus.

Ascites. Problems with liver function can cause fluid to build up in the abdomen, called ascites. Ascites can lead to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, a serious infection that requires immediate medical attention. Ascites usually only lasts a few weeks. If ascites lasts more than 6 weeks, cirrhosis is likely present and the infant will probably need a liver transplant.

Bacterial cholangitis. Bacterial cholangitis is an infection of the bile ducts that is treated with bacteria-fighting medications called antibiotics.

Portal hypertension. The portal vein carries blood from the stomach, intestines, spleen, gallbladder, and pancreas to the liver. In cirrhosis, scar tissue partially blocks and slows the normal flow of blood, which increases the pressure in the portal vein. This condition is called portal hypertension. Portal hypertension can cause gastrointestinal bleeding that may require surgery and an eventual liver transplant.

Pruritus. Pruritus is caused by bile buildup in the blood and irritation of nerve endings in the skin. Prescription medication may be recommended for pruritus, including resins that bind bile in the intestines and antihistamines that decrease the skin’s sensation of itching.

[Top]

What medical care is needed after a liver transplant?

After a liver transplant, a regimen of medications is used to prevent the immune system from rejecting the new liver. Health care providers may also prescribe blood pressure medications and antibiotics, along with special diets and vitamin supplements.

[Top]

Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

Infants with biliary atresia often have nutritional deficiencies and require special diets as they grow up. They may need a higher calorie diet, because biliary atresia leads to a faster metabolism. The disease also prevents them from digesting fats and can lead to protein and vitamin deficiencies. Vitamin supplements may be recommended, along with adding medium-chain triglyceride oil to foods, liquids, and infant formula. The oil adds calories and is easier to digest without bile than other types of fats. If an infant or child is too sick to eat, a feeding tube may be recommended to provide high-calorie liquid meals.

After a liver transplant, most infants and children can go back to their usual diet. Vitamin supplements may still be needed because the medications used to keep the body from rejecting the new liver can affect calcium and magnesium levels.

[Top]

Points to Remember

- Biliary atresia is a life-threatening condition in infants in which the bile ducts inside or outside the liver do not have normal openings.

- The first symptom of biliary atresia is jaundice—when the skin and whites of the eyes turn yellow. Other symptoms include dark urine, gray or white stools, and slow weight gain and growth.

- Biliary atresia likely has multiple causes, though none is yet proven.

- No single test can definitively diagnose biliary atresia, so a series of tests is needed, including a blood test, abdominal x ray, ultrasound, liver scans, liver biopsy, and diagnostic surgery.

- Initial treatment for biliary atresia is usually the Kasai procedure, an operation where the bile ducts are removed and a loop of intestine is brought up to replace them.

- The definitive treatment for biliary atresia is liver transplant.

- After a liver transplant, a regimen of medications is used to prevent the immune system from rejecting the new liver. Health care providers may also prescribe blood pressure medications and antibiotics, along with special diets and vitamin supplements.

[Top]

Hope through Research

Researchers are studying the possible causes of biliary atresia and new ways to diagnose and treat it. One of the largest research initiatives is the ChiLDREN (the Childhood Liver Disease Research and Education Network), a consortium of centers funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). More information about ChiLDREN’s clinical trials, funded under National Institutes of Health clinical trial number NCT00061828, can be found at www.childrennetwork.org ![]() .

.

The network comprises 15 liver disease and transplant centers and one data-coordinating center. The centers work together to coordinate research and share ideas and resources. The network enrolls infants with biliary atresia in a large study to evaluate the best ways of managing the disease and to carry out clinical trials of new and promising treatments or approaches for diagnosis and monitoring the disease. Biliary atresia is a rare disease; therefore, only a network of centers can identify enough infants with this disease to carry out studies of new therapies.

Centers collect blood, tissue, and other samples from infants with biliary atresia so researchers can learn more about biliary atresia and find better treatments. An important goal of ChiLDREN is to help find the causes of biliary atresia and make recommendations for early detection and proper management.

Participants in clinical trials can play a more active role in their own health care, gain access to new research treatments before they are widely available, and help others by contributing to medical research. For information about current studies, visit www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

[Top]

For More Information

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

1001 North Fairfax Street, Suite 400

Alexandria, VA 22314

Phone: 703–299–9766

Fax: 703–299–9622

Email: aasld@aasld.org

Internet: www.aasld.org ![]()

American Liver Foundation

39 Broadway, Suite 2700

New York, NY 10006

Phone: 1–800–GO–LIVER (1–800–465–4837) or 212–668–1000

Fax: 212–483–8179

Email: info@liverfoundation.org

Internet: www.liverfoundation.org ![]()

Children’s Liver Association for Support Services

25379 Wayne Mills Place, Suite 143

Valencia, CA 91355

Phone: 1–877–679–8256 or 661–263–9099

Fax: 661–263–9099

Email: info@classkids.org

Internet: www.classkids.org ![]()

[Top]

Acknowledgments

Publications produced by the Clearinghouse are carefully reviewed by both NIDDK scientists and outside experts. This publication was originally reviewed by ChiLDREN investigators: Ronald Sokol, M.D., University of Colorado/The Children’s Hospital of Denver; Jorge Bezerra, M.D., Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center; and Benjamin Shneider, M.D., Mount Sinai Hospital of New York. The original illustration of the Kasai procedure was provided by Julie Porter.

You may also find additional information about this topic by visiting MedlinePlus at www.medlineplus.gov.

This publication may contain information about medications. When prepared, this publication included the most current information available. For updates or for questions about any medications, contact the U.S. Food and Drug Administration toll-free at 1–888–INFO–FDA (1–888–463–6332) or visit www.fda.gov. Consult your health care provider for more information.

[Top]

National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

2 Information Way

Bethesda, MD 20892–3570

Phone: 1–800–891–5389

TTY: 1–866–569–1162

Fax: 703–738–4929

Email: nddic@info.niddk.nih.gov

Internet: www.digestive.niddk.nih.gov

The National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NDDIC) is a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The NIDDK is part of the National Institutes of Health of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Established in 1980, the Clearinghouse provides information about digestive diseases to people with digestive disorders and to their families, health care professionals, and the public. The NDDIC answers inquiries, develops and distributes publications, and works closely with professional and patient organizations and Government agencies to coordinate resources about digestive diseases.

This publication is not copyrighted. The Clearinghouse encourages users of this publication to duplicate and distribute as many copies as desired.

NIH Publication No. 12–5289

July 2012

[Top]

Page last updated August 1, 2012