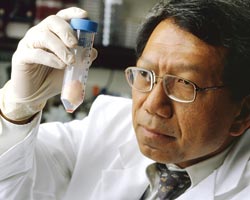

Rocky Tuan, Ph.D., Chief of the Cartilage Biology and Orthopaedics Branch, holds a vial containing knee cartilage that was recovered from a total knee replacement. Part of his research is to engineer cartilage tissues that can be used to repair damaged joint cartilage.

Photo: NIAMS

NIH researcher Dr. Rocky S. Tuan is helping to pioneer breakthroughs in how doctors deal with problems affecting their patients' tendons, ligaments, and other soft tissues—including their replacement.

Dr. Rocky S. Tuan is passionate about what, literally, connects us as human beings: the cartilage, ligaments, tendons, discs, and other soft tissue that hold the skeleton together, making movement possible. As Chief of the Cartilage Biology and Orthopaedics Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis, and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, he heads a team of biologists, engineers, and clinical researchers who are pioneering advances in soft tissue development. He spoke about his research recently with NIH MedlinePlus magazine coordinator Christopher Klose.

For background, why are back and joint problems and diseases so important?

Dr. Tuan: Your musculoskeletal system is the body's largest system. Arthritis, back and joint pain, osteoporosis, and other problems can make life miserable. Though typically not life threatening, they are one of the most common reasons people go to the doctor. They're a huge economic burden for society, too.

What is the biggest problem?

Dr. Tuan: The biggest one is osteoarthritis. It affects 27 million Americans over the age of 25. As the population ages, the number of people with osteoarthritis will only continue to grow.

What causes osteoarthritis?

Dr. Tuan: Aging is a prime factor—wear and tear. Also, genetics and lifestyle can play a role. Both men and women have the disease, but it's more common in people who are overweight and in those with jobs that stress particular joints.

How does the disease work?

Dr. Tuan: There's damage or a tear in the cartilage. It worsens and pieces fall out, causing pain. The joint tissues are irritated and the body reacts by forming more tissue, known as "bone spurs." Pain increases, movement decreases, and something must be done.

What's the treatment for crippling osteoarthritis?

Dr. Tuan: Total joint replacements. They're a miracle. They restore activity and a person's self-esteem. But the problem is that artificial joints only last for 10 or 15 years, if you don't abuse them. That may be acceptable if you're in your 70s or 80s, but not in your 30s or 40s. You'll need another knee or hip—or two!

Are there any alternatives to joint replacement?

Dr. Tuan: Yes. In sports-related injuries, for example, one of the newest alternatives is cartilage or cartilage cell transplantation. But it is not very efficient, requires many surgeries—with lots of little stitches, and cannot repair large defects.

Are you and your team working on new methods for cartilage replacement?

Dr. Tuan: Yes. Our goal is to mimic nature—to create a biological cure, not a mechanical fix. The idea is to grow a patient's own bone marrow stem cells, the ones that make connective tissues, outside the body into large pieces of cartilage, and then transplant the cartilage back into the patient. It's like a skin graft.

What's another area you're working on?

Dr. Tuan: Low back pain; specifically, engineering discs to treat low back pain. There is a huge need for such treatment. Now the disc is removed entirely and the vertebrae fused together. This stops the pain but lessens the patient's mobility, which can lead to other problems.

Using tiny, biodegradable fibers seeded with adult stem cells, we've made a prototype disc which is remarkably similar to the natural disc. We will be testing it in the laboratory shortly to see how it performs.

"We're close to a touchdown"

Are you working on injuries to our soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan?

Dr. Tuan: Yes, especially injuries to the arms and legs. We hope that what we're learning can also be applied in civilian life. Previous studies have found that amputees frequently develop abnormal bone formation around the amputation site. This slows healing and makes it difficult—and painful—to fit prosthetic arms and legs.

Inside the traumatized muscles, we have discovered the cells responsible for abnormal bone formation. Interestingly, we have also found that these cells can stimulate nerve growth! So we are experimenting to see if we can stimulate them to repair the peripheral nerves damaged from injury and amputation.

How do you assess what you're doing?

Dr. Tuan: In all these areas, we are trying to solve very complicated questions. How to make cartilage, for example? Or keep adult stem cells young? I tell my team, "The ball is still in the air, but we're close to a touchdown."