For Federal, State, Local and Tribal Officials

Rapid Response Teams

What are the Rapid Response Teams (RRTs)?

The Food Protection RRTs conduct integrated, multiagency responses to all-hazards food and feed emergencies in various states across the Nation. RRTs are developed through a multiyear cooperative agreement between FDA and State food regulatory partners. There are currently nineteen (19) RRTs within the Project. This cooperative agreement requires that these teams engage partners across disciplines and jurisdictions to build core capabilities and explore innovative approaches to response. The RRTs vary from each other in accordance with differences in government structures, geographies, laws, resources, etc.

Quick Links: |

View the RRT Project Overview here.

To request the RRT Best Practices Manual Volume 1, or for other questions regarding the RRT Project, please contact DFSR at dfsr@fda.hhs.gov.

Why Create RRTs?

The RRT project was created to address the need for improved, integrated rapid response to food and feed emergencies. Multiple national initiatives such as the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (2007), formation of the President’s Food Safety Working Group (2009), and the passage of the Food Safety Modernization Act (2011) all point to the priority of this issue for the Nation.

Who are the RRTs?

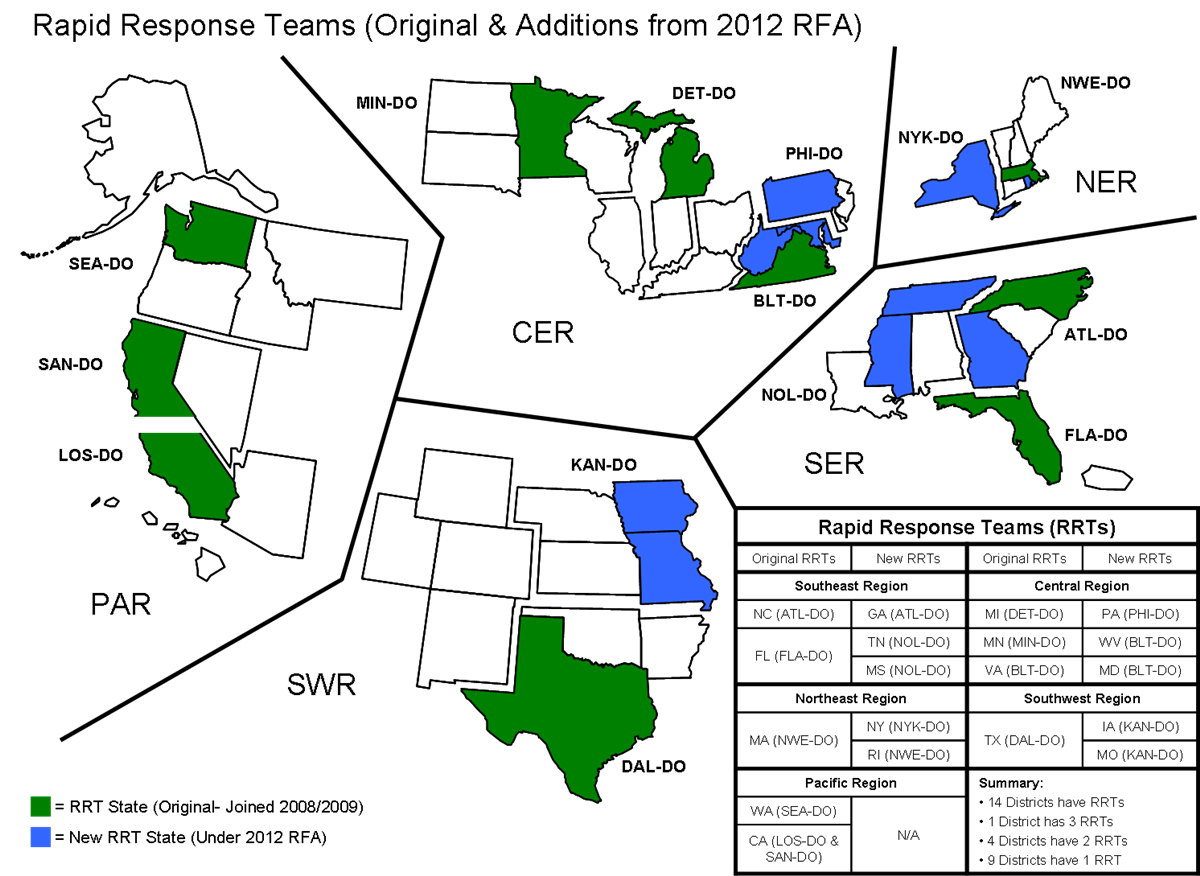

The RRT project began in 2008, with awards being made to six pilot states: CA (SAN-DO & LOS-DO), FL (FLA-DO), MA (NWE-DO), MI (DET-DO), MN (MIN-DO) and NC (ATL-DO). In 2009, the pilot was expanded to TX (DAL-DO), VA (BLT-DO) and WA (SEA-DO). In May of 2012, a new RFA (request for applications) was issued, and 10 new RRTs were awarded in August, 2012. The new RRTs are: RI (NWE-DO), NY (NYK-DO), PA (PHI-DO), MD (BLT-DO), WV (BLT-DO), TN (NOL-DO), MS (NOL-DO), GA (ATL-DO), IA (KAN-DO) and MO (KAN-DO). The map below identifies how nine states began in 2008 or 2009 (green) and ten states joined in 2012 (blue). In total, 14 ORA Districts have RRTs, where 1 District has 3 RRTs, 4 Districts have 2 RRTs and 9 Districts have 1 RRT.

Multi-Agency Collaboration

In order for RRTs to effectively respond to food emergencies, they must build extensive collaboration among multiple disciplines, such as partners in environmental health, epidemiology, laboratory, law enforcement, emergency management. This also spans federal, state, local, and other partners.

What have the RRTs Accomplished?

The nine pilot RRTs continue to develop their teams individually and as a national network. The program started when many state and local resources were encountering new financial and other challenges. However, they have taken advantage of both the similarities among their situations and their differences to create a model that can be helpful for a wide range of other partners. They have documented best practices in the RRT Best Practices Manual (described below), explored and tested new tools, and demonstrated the process and value of building partnerships to improve emergency response.

Recent RRT responses to emergencies exhibit the benefits of strengthened collaboration and capabilities on the efficiency and effectiveness of their responses. (Examples of successful stories to be posted soon.)

RRT Manual of Best Practices (RRT Playbook)

RRT Highlights & Successes

Accidental Consumption of Decoquinate Medicated Feed by a Michigan Dairy Herd: This article features the work of the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD) and their laboratory partners at Michigan State University Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health (MSU DCPAH) to respond to accidental consumption of decoquinate by dairy cattle.

Notes from the Field: Human Salmonella Infantis Infections Linked to Dry Dog Food — United States and Canada, 2012: An article published June 15, 2012 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) featured the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD). The article focuses on how a positive sample of dog food tested by MDARD as part of routine retail testing resulted in not only a recall of that single product, but contributed to an ongoing outbreak investigation and spurred additional testing by multiple agencies, which resulted in subsequent product recalls.