News & Events

Regulatory Reform Series #5 - FDA Medical Device Regulation: Impact on American Patients, Innovation and Jobs

Statement of

Jeffrey Shuren, M.D., J.D.

Director, Center for Devices and Radiological Health

Food and Drug Administration

Department of Health and Human Services

Before the

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. House of Representatives

July 20, 2011

INTRODUCTION

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee, I am Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, Director, Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA or the Agency). I am pleased to be here today to discuss CDRH’s initiatives under President Obama’s Executive Order 13563, Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review, and other activities we are undertaking to improve the predictability, consistency, and transparency of our regulatory processes.

The Impact of Regulation on Innovation

FDA is charged with a significant task: to protect and promote the health of the American public. To succeed in that mission, we must ensure the safety and effectiveness of the medical products that Americans rely on every day, and also facilitate the scientific innovations that make these products safer and more effective. These dual roles have a profound effect on the nation’s economy. FDA’s premarket review of medical devices gives manufacturers a worldwide base of consumer confidence. Our ability to work with innovators to translate discoveries into products that can be cleared or approved in a timely way is essential to the growth of the medical products industry and the jobs it creates. U.S.-based companies dominate the roughly $350 billion global medical device industry. The U.S. medical device industry is one of the few sectors, in these challenging economic times, with a positive trade balance.[1] In 2000, the U.S. medical device industry ranked 13th in venture capital investment—now, 10 years later, it’s our country’s fourth largest sector for venture capital investment.[2] And, the medical device industry has produced a net gain in jobs since 2005, even while overall manufacturing employment has suffered. According to a recent industry survey, “If you listen to what CEOs are saying, the industry should experience healthy growth in employee headcount in 2011” (Emergo Group, “Medical Device Industry Outlook” (December 2010), available at http://www.emergogroup.com/files/2011-medical-devices-industry-outlook-webinar-version.pdf).

As noted in a January 2011 report on medical technology innovation by PwC (formerly PriceWaterhouseCoopers), the U.S. regulatory system and U.S. regulatory standard have served American industry and patients well. As that report states, “U.S. success in medical technology during recent decades stems partially from global leadership of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA’s standards and guidelines to ensure safety and efficacy have instilled confidence worldwide in the industry’s products. Other countries’ regulators often wait to see FDA’s position before acting on medical technology applications, and often model their own regulatory approach on FDA’s.”

In terms of time to market, data show that the United States is performing as well or better than the European Union (EU). An industry-sponsored analysis[3] shows that low-risk 510(k) devices without clinical data (80 percent of all devices reviewed each year) came on the market first in the United States as often as or more often than in the EU. The EU typically approves higher- risk devices faster than the United States because, unlike in the United States, the EU does not require the manufacturer to demonstrate that the device actually benefits patients.

FDA also recognizes that, if the U.S. is to maintain its leadership role in this area, we must continue to streamline and modernize our processes and procedures to make device approval not just scientifically rigorous, but clear, consistent and predictable. I will discuss our efforts in that regard in more detail later in my testimony.

The President’s Regulatory Reform Initiative

With Executive Order 13563, issued on January 18, 2011, President Obama laid the foundation for a regulatory system that is designed to protect public health and welfare, while also promoting economic growth, innovation, competitiveness, and job creation. An accompanying Wall Street Journal op-ed by the President highlighted FDA’s medical device initiatives, described in greater detail later in this testimony, as an example of the kind of efforts he was talking about. Among other things, and to the extent permitted by law, the Executive Order:

- Requires agencies to consider costs and benefits of regulation to ensure that the benefits justify the costs and to select the least-burdensome alternatives;

- Requires increased public participation and an open exchange;

- Directs agencies to take steps to harmonize, simplify, and coordinate rules; and

- Directs agencies to consider flexible approaches that reduce burdens and maintain freedom of choice for the public.

The Executive Order also requires a government-wide “look back” at existing federal regulations to review significant rules and decide which should be streamlined, reduced, improved, or eliminated. One of the goals of this approach is to eliminate unnecessary regulatory burdens and costs on individuals, businesses, and governments.

On May 18 of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS or the Department) released its Preliminary Plan. The Plan highlights regulations already being modified or streamlined and identifies additional candidates for further review.

In order to increase public participation in the retrospective review, HHS posted its Preliminary Plan for public comment at http://www.hhs.gov/open/recordsandreports/execorders/13563/draft/index.html. The comment period for HHS’ Preliminary Plan closed on June 30, 2011. HHS will now proceed to finalize the Plan.

As a first step in the regulatory review, the Secretary asked each agency to do an inventory of its existing significant regulations to provide information that will assist the Department in constructing an ongoing retrospective review process. FDA sought comment on how the Agency could revise its existing review framework to meet the objectives of Executive Order 13563, regarding the development of a plan with a defined method and schedule for identifying certain significant rules that may be obsolete, unnecessary, unjustified, excessively burdensome, or counter-productive. FDA focuses its retrospective review efforts on regulations that have a significant public health impact and regulations that impose a significant burden on the Agency and/or industry. FDA has under review, or has identified, over 40 rules as candidates for regulatory review.

On April 27, 2011, FDA published a notice in the Federal Register, requesting comment and supporting data on which, if any, of our existing rules are outmoded, ineffective, insufficient, or excessively burdensome and thus may be candidates for review. This docket closed on June 27. FDA is now reviewing the comments received and will be using the comments to inform its future regulatory review activities.

Detailed information about FDA’s regulatory review activities can be found at

http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/Transparency/TransparencyInitiative/ucm251751.htm.

There you will also find some of the activities FDA is undertaking in support of Executive Order 13563. For example, in an effort to regulate based on risks and reduce regulatory burden, we are reviewing classifications of medical devices to determine if down-classification (i.e., moving a device to a classification with less stringent requirements) is appropriate. Two weeks ago, consistent with its commitment under the Medical Device User Fee Amendments of 2007, FDA issued draft guidance describing its intent to exercise enforcement discretion with respect to premarket notification requirements for 30 different in vitro diagnostic and radiology device types with well-established safety and effectiveness profiles. The devices include common urine and blood tests, alcohol breath tests, blood clotting protein tests, and radiology device accessories, such as film cassettes, film processors, and digitizers. We intend to exempt these devices from premarket notification requirements through the appropriate regulatory processes. We will, of course, continue to enforce all other applicable requirements.

In addition, we are updating existing regulations, such as converting the device registration and listing process to a paperless system, allowing for the utilization of the latest technology in the collection of information, while maintaining an avenue for companies for which paper applications are more convenient.

We are instituting a paperless, electronic Medical Device Reporting system, which will speed reporting and analysis of adverse events and identification of emerging public health problems, as well as lower costs for manufacturers.

We are revising device premarket approval regulations (Special PMA Supplement Changes Being Effected) to remove duplicative requirements and to streamline and clarify regulatory requirements. And we will be proposing to allow the use of validated symbols in device labeling, without the need for accompanying English text, thereby reducing the burden of labeling requirements by permitting harmonization with labeling for international markets.

FDA’s Medical Device Regulatory Reform Initiatives

Federal agencies have long had to consider the various impacts of regulations on industry and the public. The laws and guidance documents that FDA follows require it to measure the effect of regulations on employment, innovation, and economic growth. For example, the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act of 1995 requires that major rules include estimated effects on employment, competitiveness, and growth. Executive Order 12866, Regulatory Planning and Review, requires all federal agencies to consider effects on innovation when writing regulations.

In addition, agencies periodically conduct reviews of existing regulations pursuant to a variety of authorities, changes in the law, or other circumstances. For example, the Regulatory Flexibility Act requires agencies to conduct reviews within 10 years of regulations that have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small businesses. And, under 21 CFR 10.25(a) and 10.30, FDA may review a regulation if a person submits a petition asking the Commissioner to issue, amend, or revoke a regulation.

In this spirit of openness and transparency, in 2010, CDRH initiated its own review of its process for premarket review of medical devices and undertook two significant initiatives to improve the Agency’s medical device premarket review programs.

It’s important to note that, in terms of performance, FDA has been consistently strong, meeting or exceeding goals agreed to by FDA and industry under the Medical Device User Fee Amendments (MDUFA) for approximately 95 percent of the submissions we review each year. FDA consistently completes at least 90 percent of 510(k) reviews within 90 days or less. In the limited areas, where FDA is not yet meeting its MDUFA goals, the Agency’s performance has been steadily improving, despite growing device complexity and an increased workload, without a commensurate increase in user fees.

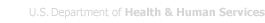

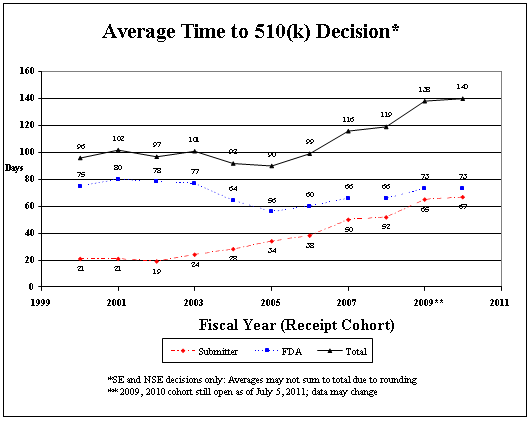

MDUFA metrics reflect FDA time only; they do not reflect the time required for industry to respond to requests for additional information. As the graphs below illustrate, while the time FDA spends reviewing an application has improved for both low- and high-risk devices, overall time to decision—the time that FDA has the application, plus the time the manufacturer spends answering any questions FDA may have —has increased. FDA bears some responsibility for the increase in approval times and has been instituting management changes. As a result, in 2010, total time for 510(k)s appears to have stabilized and preliminary data suggest that the total time for PMA decisions is improving.

Industry also bears some responsibility for the increase in overall time to decision, which I discuss in detail on page 15 of my testimony.

The 510(k) Action Plan

FDA recognizes that concerns have been raised about how well CDRH’s premarket review program is meeting its two goals of ensuring that medical devices are safe and effective and fostering medical device innovation. Some stakeholders—particularly in industry—have argued that a lack of predictability, consistency, and transparency in the 510(k) program is stifling medical device innovation in the United States and driving companies (and jobs) overseas. Other groups, including health care professional, patient, and third-party payer organizations, have argued that the 510(k) program allows devices to enter the market without sufficient evidence of safety and effectiveness, thereby putting patients at unnecessary risk and failing to provide practitioners with the necessary information to make well-informed treatment and diagnostic decisions.

In response to these concerns—and because FDA is continually looking for ways to improve its performance in helping to bring safe and effective devices to market—the Agency conducted an assessment of the 510(k) review program and an assessment of how it uses science in regulatory decision-making, which addressed aspects of its other premarket review programs.

The two reports we released publicly in August 2010, with our analyses and recommendations, showed that we have not done as good a job managing our premarket review programs as we should and that we needed to take several critical actions to improve the predictability, consistency, and transparency of these programs.

For example, we have new reviewers who need better training. We need to improve management oversight and standard operating procedures. We need to provide greater clarity for our staff and for industry through guidance about key parts of our premarket review and clinical trial programs and how we make benefit-risk determinations. We need to provide greater clarity for industry through guidance and greater interactions about what we need from them to facilitate more efficient, predictable reviews. We need to make greater use of outside experts who understand cutting-edge technologies. And we need to find the means to handle the ever- increasing workload and reduce staff and manager turnover, which is almost double that of the FDA’s drugs and biologics centers.

The Agency solicited public comment on the recommendations identified in the studies and received a range of perspectives from stakeholders throughout the process at two public meetings and three town hall meetings, through three open public dockets and via many meetings with stakeholders. Seventy-six (76) comments were submitted from medical device companies, industry representatives, venture capitalists, health care professional organizations, third-party payers, patient and consumer advocacy groups, foreign regulatory bodies, and others.

After considering the public input, in January 2011, FDA announced 25 specific actions that the Agency will take this year to improve the predictability, consistency, and transparency of our premarket review programs. Since then, FDA has announced additional efforts, including actions to improve its program for clinical trials and Investigational Device Exemptions (IDEs) program. These are based on an analysis of this program that the Agency committed to, as part of its January 2011 announcement.

These actions, many of which were supported by industry, include:

- Developing a range of updated and new guidances to clarify CDRH requirements for timely and consistent product review, including device-specific guidance in several areas such as mobile applications and artificial pancreas systems (to be completed by the end of 2011);

- Revamping the guidance development process through a new tracking system and core staff to oversee the timely drafting and clearance of documents (to be completed by the end of 2011);

- Improving communication between FDA and industry through enhancements to interactive review (some of these enhancements will be in place by the end of 2011);

- Streamlining the de novo review process, to provide a more efficient pathway to market for novel devices that are low to moderate risk. This new structure will be described in draft guidance for industry that is expected to be available for public comment by September 30, 2011;

- Streamlining the clinical trial and IDE processes by providing industry with specific guidance on how to improve the quality and performance of clinical trials. (IDEs are required before device testing in humans may begin, and they ensure that the rights of human subjects are protected while gathering data on the safety and efficacy of medical products.) We are also developing guidance to clarify the criteria for approving clinical trials, and criteria for when a first-in-human study can be conducted earlier during device development (to be issued by October 31, 2011);

- Establishment of an internal Center Science Council to actively monitor the quality and performance of the Center’s scientific programs and ensure consistency and predictability in CDRH scientific decision-making (already completed);

- Creating a network of experts to help the Center resolve complex scientific issues, which will ultimately result in more timely reviews. This network will be especially helpful as FDA confronts new technologies;

- Instituting a mandatory Reviewer Certification Program for new reviewers (to be completed by September 2011); and,

- Instituting a pilot Experiential Learning Program to provide review staff with real-world training experiences as they participate in visits to manufacturers, research and health care facilities, and academia (to begin in early 2012).

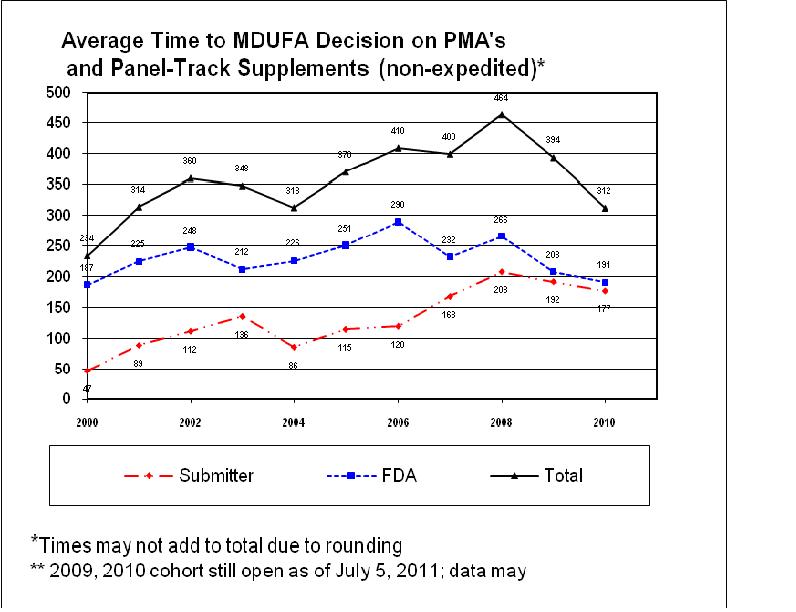

Consistent with the improvements we are making to the program, we are seeing a positive trend in the percent of 510(k) decisions that are “not substantially equivalent” (NSE). For manufacturers, an NSE determination often represents an inefficient use of time and resources. For FDA, NSE determinations require significant Agency resources and time, yet fail to result in the marketing of a new product. The following chart shows an upward trend, until mid-2010, in the percentage of 510(k) decisions that were “not substantially equivalent” (NSE). The most common reasons that 510(k) submissions result in NSE determinations are: lack of a suitable predicate device; intended use of the new device is not the same as the intended use of the predicate; technological characteristics are different from those of the predicate and raise new questions of safety and effectiveness; and/or performance data failed to demonstrate that the device is as safe and effective as the predicate. The vast majority of NSE decisions are due to the absence of adequate performance data, sometimes despite repeated FDA requests.

I’m pleased to report that, consistent with our many improvements to the 510(k) program, this long-standing trend is turning around. From a peak of 8 percent in 2010, the NSE rate has decreased to 5 percent through the first eight months of 2011.

Percent of 510(k) Submissions with an NSE Decision per Year

In addition, we need to ensure that industry meets its responsibility to provide us with appropriate data. Poor quality submissions are significant contributors to delays in premarket reviews; these include submissions that do not adhere to current guidance documents, that contain inadequate clinical data (e.g., missing data, or data that fail to meet endpoints), or that deviate from the study protocol agreed upon.

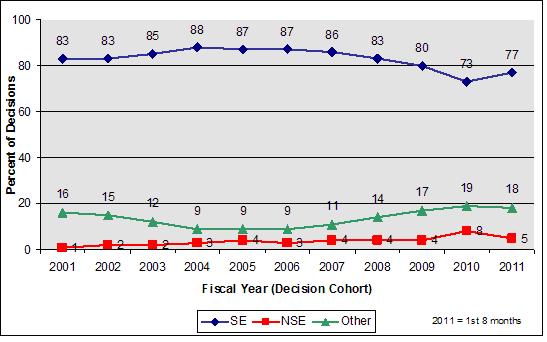

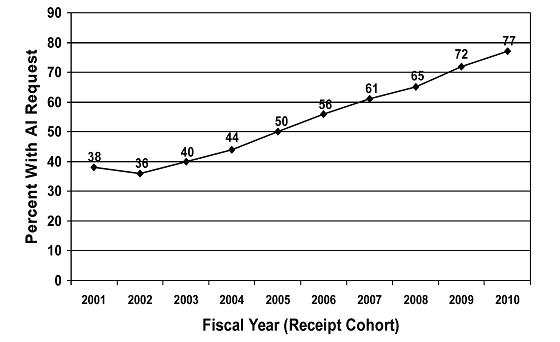

The following chart shows the steep and prolonged increase, since FY 2002, in the percentage of 510(k) submissions requiring an Additional Information (AI) letter after the first review cycle. The increasing number of AI letters has contributed to the increasing total time from submission to decision. In over 80 percent of cases, the AI letter was sent because of problems with the quality of the submission. Examples of submission quality problems that result in the increasing rate of AI letters include: inadequate device descriptions; discrepancies throughout the submission, e.g., between the indications for use and labeling materials; problems with the proposed indications for use; completely missing performance testing data; completely missing clinical data; and failure to follow the applicable guidance document without explanation. These submission quality problems waste FDA and sponsor time and resources and divert FDA resources from pending, higher-quality applications.

Percent of 510(k) Submissions with an AI Letter in First Review Cycle per Year

We are pleased that, in response to FDA calls for improving the quality of premarket submissions, AdvaMed has improved and made more available training courses for its companies to help them develop 510(k) and PMA submissions that meet FDA standards.

Innovation Initiative

Facilitating medical device innovation is a top priority for FDA. As part of its 2010 and 2011 Strategic Plans, FDA’s medical device center has set goals to proactively facilitate innovation to address unmet public health needs. FDA’s Innovation Initiative seeks to accelerate the development and regulatory evaluation of innovative medical devices, strengthen the nation’s research infrastructure for developing breakthrough technologies, and advance quality regulatory science. As part of this initiative, CDRH proposed additional actions to encourage innovation, streamline regulatory and scientific device evaluation, and expedite the delivery of novel, important, safe and effective innovative medical devices to patients, including:

- Establishing the Innovation Pathway, a priority review program to expedite development, assessment, and review of important technologies;

- Issuing guidance on leveraging clinical studies conducted outside the United States;

- Advancing regulatory science through public-private partnerships;

- Facilitating the creation of a publicly available core curriculum for medical device development and testing to train the next generation of innovators; and

- Engaging in formal horizon scanning—the systematic monitoring of medical literature and scientific funding to predict where technology is heading, in order to prepare for and respond to transformative, innovative technologies and scientific breakthroughs.

A public docket has been set up to solicit public comment on the Innovation Initiative proposals, and a public meeting on the topic took place on March 15, 2011. In the near future, FDA will announce actions it plans to take under the Initiative.

The Role of Regulation in Patient Safety

As we continue to look for ways to improve our ability to facilitate innovation and to speed safe and effective products to patients, we must not lose sight of the benefits of smart regulation, to the industry, patients, and society. Medical device regulation results in better, safer, more effective treatments and world-wide confidence in, and adoption of, the devices that industry produces.

We at FDA see daily the kinds of problems that occur with medical devices that are poorly designed or manufactured, difficult to use, and/or insufficiently tested. For example, we received an IDE, or request to initiate a clinical trial, for the PleuraSeal Lung Sealant System, which was indicated to prevent Persistent Air Leaks (PALs) resulting from lung surgery. The IDE was designed to test whether the device would help to seal an incision in the lung better than the standard of care—i.e., stitches—alone. The company began marketing the device outside the United States for prevention of PALs in November 2007, and then began its clinical study to support approval in the United States. Midway through the study, it was apparent that three times more patients who received PleuraSeal had poor outcomes (PALs) as compared to patients whose incisions were closed using standard techniques. This showed that PleuraSeal was not effective in preventing PALs after lung surgery. Subsequent to discovering these results, the manufacturer announced a worldwide recall of all PleuraSeal lung sealant systems. PleuraSeal was removed from the market in the EU and the IDE was withdrawn. This device was never approved in the U.S.

As another example, an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is caused by a weakened area in the aorta, the main blood vessel that supplies blood from the heart to the rest of the body. When blood flows through the aorta, the pressure of the blood against the weakened wall causes it to bulge like a balloon.

FDA received the first IDE, or request for approval of a clinical trial, for an AAA stent graft in 1994. Premarket problems were identified during clinical testing related to delivery and deployment, stability of fixation and structural integrity of these devices. As result of the findings of the studies, FDA required study suspension, redesign, or initiation of new studies for nine AAA stent grafts.

AAA Stent Grafts were marketed in Europe as early as 1997, and were put on the market there without the support of clinical studies as is required in the U.S. Postmarket reports identified serious problems with the devices on the EU market, including late rupture of the aneurysm, persistent leaks, continued AAA enlargement, graft obstruction, fracture, migration and kinking. Six devices have been permanently discontinued in the EU due to complications, and three were redesigned and reintroduced.

The Aptus AAA stent graft incorporated an innovative staple technology that prevented the graft from migrating following implantation. However, patients developed blood clots in their arms and legs after enrollment in a U.S.-based pivotal clinical trial in February 2009. The problems were not predicted by preclinical testing. The Aptus AAA stent graft is approved in the EU and is not approved for marketing in the United States.

There are currently six AAA Stent Grafts on the U.S. market. None has been withdrawn from the U.S. market due to these failures.

Outside the United States, pressure is growing toward greater premarket scrutiny of medical devices. A recent report[4] concluded that “For innovative high-risk devices the future EU Device Directive should move away from requiring clinical safety and “performance” data only to also require pre-market data that demonstrate “clinical efficacy,” and “The device industry should be made aware of the growing importance of generating clinical evidence and the specific expertise this requires.”

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recently issued a “case for reform” of the European medical device regulatory system and their recommendations included creating a unified system, stronger clinical data requirements, and more accountability for notified bodies.[5] The ESC cites examples of many different cardiovascular technologies that were implanted in patients in the EU that were then proven to be unsafe and/or ineffective through clinical trials required under the U.S. system and removed from the European market. A recent article in the British Medical Journal discusses the opacity of the European medical device regulatory system, with regard to access to decisions regarding device clearances.[6] The article cites the FDA system’s transparency as helping physicians to make informed decisions on which devices to use and giving patients access to information on devices that will be used on them.

Additionally, a report released by the Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre[7] calls upon the European Commission to implement reforms to make the EU review process for high-risk devices more like that of the United States.

CONCLUSION

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee, I share your goal of smart, streamlined regulatory programs. The Department’s plan for regulatory reform under President Obama’s Executive Order will heighten and maintain the focus on this important principle. Thank you, for your commitment to the mission of FDA, and the continued success of our medical device program, which helps get safe and effective technology to patients and practitioners on a daily basis. I am happy to answer questions you may have.

_____________________________________________________________

[1] PwC (formerly PriceWaterhouseCoopers), “Medical Technology Innovation Scorecard” (January 2011) at page 8, available at http://pwchealth.com/cgi-local/hregister.cgi?link=reg/innovation-scorecard.pdf.

[2] PriceWaterhouseCoopers/National Venture Capital Association, MoneyTree™ Report, Data: Thomson Reuters, Investments by Industry Q1 1995 – Q4 2010, available at http://www.nvca.org.

[3] California Healthcare Institute and The Boston Consulting Group, “Competitiveness and Regulation: The FDA and the Future of America’s Biomedical Industry” (Feb. 2011), available at http://www.bdg.com/documents/file72060.pdf.

[4] Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre, “The Pre-market Clinical Evaluation of Innovative High-risk Medical Devices,” KCE Reports 158 (2011) at p. vii, available at http://www.kce.fgov.be/index_en.aspx?SGREF=20267.

[5] See “Clinical evaluation of cardiovascular devices: principles, problems, and proposals for European regulatory reform,” Fraser, et al., European Heart Journal, May 2011.

[6] See “Medical-device recalls in the UK and the device-regulation process: retrospective review of safety notices and alerts,” Heneghan, et al., British Medical Journal, May 2011.

[7] See “The pre-market clinical evaluation of innovative high-risk medical devices,” KCE reports 158C, Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre, 2011.