| |

|||

|

American Folklife:

|

|

|

Folklife is society welcoming new members at bris and christening, and keeping the dead incorporated on All Saints Day. It is the marking of the Jewish New Year at Rosh Hashanah and the Persian New Year at Noruz. It is New York City's streets enlivened by Lion Dancers in celebration of Chinese New Year and by Southern Italian immigrants dancing their towering giglios in honor of St. Paulinus each summer. It is the ubiquitous appearance of yellow ribbons to express a complicated sentiment about war, and displays of orange pumpkins on front porches at Halloween.

Folklife is the recycling of scraps of clothing and bits of experience into quilts that tell stories, and the stories told by those gathered around quilting frames. It is the evolution of vaqueros into buckaroos, and the variety of ways there are to skin a muskrat, preserve shuck beans, or join two pieces of wood. It is the oysterboat carved into the above-ground grave of the Louisiana fisherman, and the eighteen-wheeler on the trucker's tombstone in Illinois.

Folklife is the thundering of foxhunters across the rolling Rappahanock hunt country, and the listening of hilltoppers to hounds crying fox in the Tennessee mountains. It is the twirling of lariats at western rodeos, and the spinning of double-dutch jumpropes in West Philadelphia. It is scattered across the landscape in Finnish saunas and Italian vineyards; engraved in the split rail boundaries of Appalachian "hollers" and in the stone fences around Catskill "cloves"; scrawled on urban streetscapes by graffiti artists; and projected on skylines into which mosques, temples, steeples, and onion domes taper.

Folklife is community life and values, artfully expressed in myriad interactions. It is universal, diverse, and enduring. It enriches the nation and makes us a commonwealth of cultures.

Folklore, Folklife, and the American Folklife Preservation Act

The study of folklore and folklife stands at the confluence of several European academic traditions. The terms folklore and folklife were coined by nineteenth-century scholars who saw that the industrial and agricultural revolutions were outmoding the older ways of life, making many customs and technologies paradoxically more conspicuous as they disappeared. In 1846 Englishman William J. Thoms gathered up the profusion of "manners, customs, observances, superstitions, ballads, proverbs, etc., of the olden time" under the single term folk-lore. In so doing he provided his colleagues interested in "popular antiquities" with a framework for their endeavor and modern folklorists with a name for their profession.

As Thoms and his successors combed the British hinterlands for "stumps and stubs" of disappearing traditions, the folklife studies movement was germinating in continental Europe. There scholars began using the Swedish folkliv and the German Volksleben to designate vernacular (or folk) culture in its entirety, including customs and material culture (the ways in which people transform their surroundings into food, shelter, clothing, tools, and landscapes) as well as oral traditions. Today the study of folklife encompasses all of the traditional expressions that shape and are shaped by cultural groups. While folklore and folklife may be used to distinguish oral tradition from material culture, the terms often are used interchangeably as well.

|

|

Over the past century the study of folklore has developed beyond the romantic quest for remnants of bygone days to the study of how community life and values are expressed through a wide variety of living traditions. To most people, however, the term folklore continues to suggest aspects of culture that are out-of- date or on the fringe -- the province of old people, ethnic groups, and the rural poor. The term may even be used to characterize something as trivial or untrue, as in "that's just folklore." Modern folklorists believe that no aspect of culture is trivial, and that the impulse to make culture, to traditionalize shared experiences, imbuing them with form and meaning, is universal among humans. Reflecting on their hardships and triumphs in song, story, ritual, and object, people everywhere shape cultural legacies meant to outlast each generation.

In 1976, as the United States celebrated its Bicentennial, the U.S. Congress passed the American Folklife Preservation Act (P.L. 94-201). In writing the legislation, Congress had to define folklife. Here is what the law says:

"American folklife" means the traditional expressive culture shared within the various groups in the United States: familial, ethnic, occupational, religious, regional; expressive culture includes a wide range of creative and symbolic forms such as custom, belief, technical skill, language, literature, art, architecture, music, play, dance, drama, ritual, pageantry, handicraft; these expressions are mainly learned orally, by imitation, or in performance, and are generally maintained without benefit of formal instruction or institutional direction.

Created after more than a century of legislation designed to protect physical aspects of heritage -- natural species, tracts of wilderness, landscapes, historic buildings, artifacts, and monuments -- the law reflects a growing awareness among the American people that cultural diversity, which distinguishes and strengthens us as a nation, is also a resource worthy of protection. In the United States, awareness of folklife has been heightened both by the presence of many cultural groups from all over the world and by the accelerated pace of change in the latter half of the twentieth century. However, the effort to conserve folklife should not be seen simply as an attempt to preserve vanishing ways of life. Rather, the American Folklife Preservation Act recognizes the vitality of folklife today. As a measure for safeguarding cultural diversity, the law signals an important departure from the once widely-held notion of the United States as a melting pot, which assumed that members of ethnic groups would become homogenized as "Americans." We no longer view cultural difference as a problem to be solved, but as a tremendous opportunity. In the diversity of American folklife we find a marketplace teeming with the exchange of traditional forms and cultural ideas, a rich resource for Americans who constantly shape and transform their cultures.

|

|

Sharing with others the experience of family life, ethnic origin, occupation, religious beliefs, stage of life, recreation, and geographic proximity, most individuals belong to more than one cultural group. Some groups have existed for thousands of years, while others come together temporarily around a variety of shared concerns -- particularly in America, where democratic principles have long sustained what Alexis de Tocqueville called the distinctly American "art of associating together."

Taken as a whole, the thousands of grassroots associations in the United States form a fairly comprehensive index to our nation's cultural affairs. Some, like ethnic organizations and churches, have explicitly cultural aims, while others spring up around common environmental, recreational, or occupational concerns. Some cultural groups may be less official: family members at a reunion, coworkers in a factory, or friends gathered to make back-porch (or kitchen, or garage) music. Other cultural groups may be more official: San Sostine Societies, chapters of Ducks Unlimited, the Mount Pleasant Basketmakers Association, volunteer fire companies, and senior citizens clubs. Sorting and re-sorting themselves into a vast array of cultural groups, Americans continually create culture out of their shared experiences.

The traditional knowledge and skills required to make a pie crust, plant a garden, arrange a birthday party, or turn a lathe are exchanged in the course of daily living and learned by imitation. It is not simply skills that are transferred in such interactions, but notions about the proper ways to be human at a particular time and place. Whether sung or told, enacted or crafted, traditions are the outcroppings of deep lodes of worldview, knowledge, and wisdom, navigational aids in an ever- fluctuating social world. Conferring on community members a vital sense of identity, belonging, and purpose, folklife defends against social disorders like delinquency, indigence, and drug abuse, which are themselves symptoms of deep cultural crises.

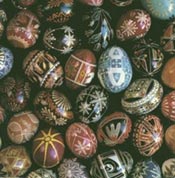

As cultural groups invest their surroundings with memory and meaning, they provide, in effect, blueprints for living. For American Indian people, the landscape is redolent of origin myths and cautionary tales, which come alive as grandmothers decipher ancient place names to their descendants. Similarly, though far from their native countries, immigrant groups may keep alive mythologies and histories tied to landscapes in the old country, evoking them through architecture, music, dance, ritual, and craft. Thus Russian immigrants flank their homes with birch trees reminiscent of Eastern Europe. The call-and-response pattern of West African music is preserved in the gospel music of African- Americans. Puerto Rican women dancing La Plena mime their Jibaro forebears who washed their clothes in the island's mountain streams. The passion of Christ is annually mapped onto urban landscapes in the Good Friday processions of Hispanic Americans, and Ukrainian-Americans, inscribing Easter eggs, overlay pre- Christian emblems of life and fertility with Christian significance.

Traditional ways of doing things are often deemed unremarkable by their practitioners, until cast into relief by abrupt change, confrontation with alternative ways of doing things, or the fresh perspective of an outsider (such as a folklorist). The diversity of American cultures has been catalytic in this regard, prompting people to recognize and reflect upon their own cultural distinctiveness. Once grasped as distinctive, ways of doing things may become emblems of participation. Ways of greeting one another, of seasoning foods, of ornamenting homes and landscapes may be deliberately used to hold together people, past, and place. Ways to wrap proteins in starches come to distinguish those who make pierogis, dumplings, pupusas, or dim sum. The weave of a blanket or basket can bespeak African American, Native American, or Middle Eastern identity and values. Distinctive rhythms, whether danced, strummed, sung, or drummed, may synchronize Americans born in the same decade, or who share common ancestry or beliefs.

Traditions do not simply pass along unchanged. In the hands of those who practice them they may be vigorously remodeled, woven into the present, and laden with new meanings. Folklife, often seen as a casualty of change, may actually survive because it is reformulated to solve cultural, social, and biological crises. Older traditions may be pressed into service for mending the ruptures between past and present, and between old and new worlds. Thus Hmong immigrants use the textile tradition of paj ntaub to record the violent events that hurled them from their traditional world in Vietnam into a profoundly different life in the United States. South Carolina sweetgrass basketmakers carry on a two- centuries-old tradition that reaches back to Africa. And a Puerto Rican street theater troupe dramatizes culture conflict on the mainland in a bilingual farce about foodways.

Retirement or the onset of old age can occasion a return to traditional crafts learned early in life. For the woman making a memory quilt or the machinist making models of tools no longer in use, traditional forms become a way of reconstituting the past in the present. The craft, the recipe, the photo album, or the ceremony serve as thresholds to a vanishing world in which an elderly person's values and identity are rooted. This is especially significant to younger witnesses for whom the past is thus made tangible and animated through stories inspired by the forms.

Cultural lineages do not always follow genealogical ones. Often a tradition's "rightful" heirs are not very interested in inheriting it. Facing indifference among the young from their own cultural groups, and pained by the possibility that their traditions might die out, masters of traditional arts and skills may deliberately rewrite the cultural will, taking on students from many different backgrounds in order to bequeath their traditions. Modern life has broadened the pool of potential heirs, making it possible for a basketmaker from New England to turn to the craft revival for apprentices, or a master of the Chinese Opera in New York to find eager students among European Americans.

|

|

The United States is not a melting pot, but neither is it a fixed mosaic of ethnic enclaves. From the beginning, our nation has been a meeting ground of many cultures, whose interactions have produced a unique array of cultural groups and forms. Responding to the challenges of life in the same locale, different ethnic groups may cast their lot together under regional identities as "buckaroos," "Pineys," "watermen," or "Hoosiers," without surrendering ethnicity in other settings. Distinctive ways of speaking, fiddling, dancing, making chili, and designing boats can evolve into resources for expressing and celebrating regional identity. Thus ways of shucking oysters or lassoing cattle can become touchstones of identity for itinerant workers, distinguishing Virginians from Marylanders or Texans from Californians. And in a Washington, D.C., neighborhood, Hispanic- Americans from various South and Central American countries explore an emerging Latino identity, which they express through an annual festival and parade that would not occur in their countries of origin.

Over the past two centuries, the intercultural transactions that are so distinctly American have produced uniquely New World blends whose origins we no longer recognize. When one tradition is spotlighted, others fade into the background. We tend to forget that the banjo, now played almost exclusively by white musicians, was a cultural idea introduced here by African-Americans, and that the tradition of lining out hymns that today flourishes mainly in African American churches is a legacy from England. Without this early nineteenth-century interchange, perhaps these distinct traditions would have disappeared. And out of the same cultural encounters in the upper South that produced these transfers, there grew distinctly American styles of music suffused with African- American ideas of syncopation.

Other forgotten legacies of early cultural encounters spangle the landscape. Early American watermen freely combined ideas from English punts, Swedish flatboats, and French bateaus to create small wooden boats that now register subtleties of wind, tide, temperature, and contours of earth beneath far-flung waters of the United States. Thus have Jersey garveys, Ozark john boats, and Mackenzie River skiffs become vessels conveying regional identity. The martin birdhouse complexes commonly found in yards east of the Mississippi River hail from gourd dwellings that American Indians devised centuries ago to entice the insect-eating birds into cohabitation. Descendants of those American Indians now live beyond the territory of martins, while the descendants of seventeenth-century martins live in houses modeled on Euro- American architectural forms.

The early colonists' adoption of an ingenious form of mosquito control exemplifies a strong pattern throughout our history, the pattern of one group freely borrowing and transforming the cultural ideas of another. We witness the continuance of this pattern in the appropriation of the Greek bouzouki by Irish-American musicians, in the influence of Cajun, Yiddish, and African styles on popular music, in the co-opting of Cornish pasties by Finnish Minnesotans, and in the embracing of ancient Japanese techniques of joinery by American woodworkers.

American folklife stoutly resists the effects of a melting pot. If it simmers at all it is in many pots of gumbo, burgoo, chili, goulash, and booya. And the American people are the chefs, concocting culture from the resources and ideas in the American folklife repertory. Folklife flourishes when children gather to play, when artisans attract students and clientele, when parents and grandparents pass along their traditions and values to the younger generations, whether in the kitchen or in an ethnic or parochial school. Defining and celebrating themselves in a constantly changing world, Americans enliven the landscape with parades, sukkos, and powwows, seasonally inscribing their worldviews on doorways and graveyards, valiantly keeping indeterminacy at bay. Our common wealth circulates in a free flowing exchange of cultural ideas, which on reflection appear to merge and diverge, surface and submerge throughout our history like contra dancers advancing and retiring, like stitches dropped and retrieved in the hands of a lacemaker, like strands of bread ritually braided, like the reciprocating bow of a master fiddler.

Folklorists

|

|

As a field of study, folklore straddles the humanities and social sciences. Like cultural anthropologists, folklorists conduct much of their research by observing and interviewing people "in the field." An interest in human expressions links folklorists with humanities scholars as well. However, unlike their colleagues in the humanities concerned with the study of written texts, folklorists attend to living traditions, curious about how they are created, transformed over time and space, and rendered meaningful.

Since the American Folklore Society was founded in 1888, its membership has increased from 105 to some 1500 people, many of whom hold advanced degrees in folklore. Fifteen colleges and universities in North America now offer such degrees, while nearly eighty other institutions offer concentrations in folklore. Some folklorists teach in universities and colleges, training others to become folklorists or contributing their perspective to the intellectual life of departments in related fields such as English, anthropology, American studies, art history, historic preservation, and musicology. Others (including many in universities and colleges) work closely with cultural groups to educate the wider public about folklife and its significance. Folklorists are involved in public programs at local, regional, state, and national levels. They often are affiliated with museums, libraries, arts organizations, public schools, and historical societies, and some work for a growing network of public folklife programs and organizations. Most states, and a number of major cities, now employ folklorists who carry out a variety of activities related to the presentation and preservation of the cultural traditions in their regions.

Because living people and cultures are what folklorists study, scholars must be sensitive to the potential effect of scholarly research upon traditions and their practitioners. Increasingly, folklorists are called upon to serve as middlemen between mainstream cultural institutions and traditional cultural groups. Today, for example, folklorists may be found helping health care professionals to accommodate their practice to patients whose traditional beliefs about illness and health are at odds with contemporary medical views. Folklorists may speak to natural resource managers on behalf of traditional craftspeople denied access to necessary natural materials, or may help traditional artists gain access to a broader clientele in order to market their wares. Folklorists may also advise planners regarding traditional patterns of land use, or alert city council members to the impact of particular laws upon cultural cornerstones such as ethnic social clubs and marketplaces. Folklorists join with historic preservationists to identify traditional histories lodged not only in objects but in a broad array of expressive forms. Folklorists also work with professional educators in museums, parks, and classrooms to devise settings in which respected bearers of tradition may impart their wealth of knowledge and skills to the younger generations.

Although the American Folklife Preservation Act suggests that folklife can be "preserved," in truth, something as fluid and dynamic as folklife does not lend itself to preservation in the sense that buildings and material artifacts do. We can record folklife on paper, film, and tape, which we in turn preserve in archives, libraries, and museums. Such preservation does not directly protect a living culture from the outside forces that disrupt the dynamics governing cultural change from within: the department of transportation that divides an urban village with a freeway; the development of traditional hunting and gathering grounds into condominiums or wilderness preserves; or the governmental regulation that discourages languages on which cultures depend for their survival. However, the documentation of folklife may come in time to be the only record a community has of a way of life so disrupted. Ultimately, particular traditions endure because someone chooses to keep them alive, adapting them to fit changing circumstances, continually crafting new settings for their survival. Working to inform the public about folklife and its significance, folklorists can assist this process.

The American Folklife Center

In passing the American Folklife Preservation Act in 1976, Congress bolstered its call to "preserve and present American folklife" by establishing the American Folklife Center. The Center, a part of the Library of Congress, fulfills its mandate in a variety of ways. It includes the Archive of Folk Culture, which was founded in the Music Division at the Library of Congress in 1928 and has grown to become one of the most significant collections of cultural research materials in the world, including manuscripts, sound and video recordings, still photographs, and related ephemera.

The Center has a staff of professionals who conduct programs under the general guidance of the Librarian of Congress and a Board of Trustees. It serves federal and state agencies, national, international, regional, and local organizations; scholars, researchers, and students; and the general public. The Center's programs and services include field projects, conferences, exhibitions, workshops, concerts, publications, archival preservation, reference service, and advisory assistance.

About the Author

Mary Hufford is the author of One Space, Many Places: Folklife and Land Use in New Jersey's Pinelands National Reserve and many articles on American traditional culture.

| ||||