A Different Slant:

Monday, July 9th, 2012

Cassini Has a Special View of Saturn These Days - How Did It Get There?

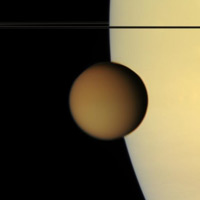

For the past 18 months, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has been orbiting Saturn in practically the same plane as the one that slices through the planet’s equator. Beginning with the Titan flyby on May 22, navigators started to tilt Cassini’s orbit in order to obtain a different view of the Saturnian system. The measure of the spacecraft orbit’s tilt relative to Saturn’s equator is referred to as its inclination. The recent Titan flyby raised Cassini’s inclination to nearly 16 degrees. Seven more Titan flybys will ultimately raise Cassini’s inclination to nearly 62 degrees by April 2013. On Earth, an orbit with a 62-degree inclination would pass as far north as Alaska and, at its southernmost point, skirt the latitude containing the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula.

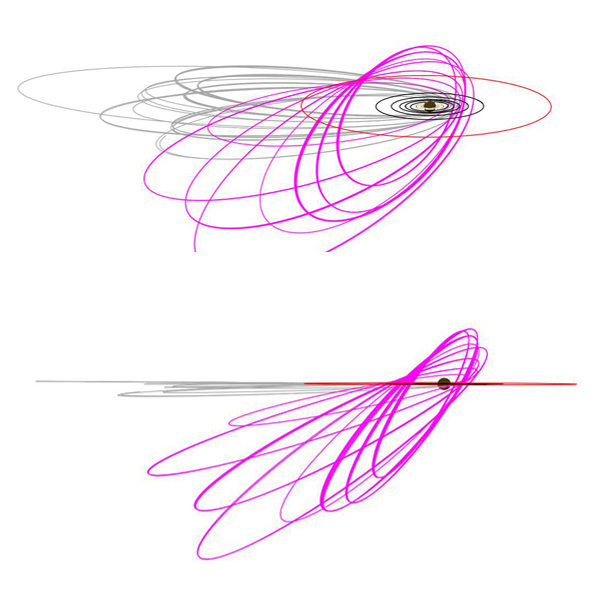

These graphics show the orbits NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has made and will make around the Saturn system from September 2010 to April 2013. As shown in gray, Cassini orbited within the plane of Saturn’s equator during the first 18 months of its current mission phase, known as the Solstice mission. Then, starting in May 2012, Cassini used the gravity of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, to tilt its orbit as shown in the magenta loops, reaching a maximum tilt of about 62 degrees in April, 2013. Titan’s orbit is shown in red. The orbits of Saturn’s inner moons are shown in black. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

These graphics show the orbits NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has made and will make around the Saturn system from September 2010 to April 2013. As shown in gray, Cassini orbited within the plane of Saturn’s equator during the first 18 months of its current mission phase, known as the Solstice mission. Then, starting in May 2012, Cassini used the gravity of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, to tilt its orbit as shown in the magenta loops, reaching a maximum tilt of about 62 degrees in April, 2013. Titan’s orbit is shown in red. The orbits of Saturn’s inner moons are shown in black. Image credit: NASA/JPL-CaltechYou may wonder why this change has been planned and how this feat is achieved. The “why” is to allow scientists to observe Saturn and the rings from different geometries in order to obtain a more comprehensive three-dimensional understanding of the Saturnian system. For instance, because Saturn’s rings lie within Saturn’s equatorial plane, they appear as a thin line when viewed by Cassini in a near-zero-degree orbit inclination. From higher inclinations, however, Cassini can view the broad expanse of the rings, making out details within individual ringlets and helping to unlock the secrets of ring origin and formation. Some of those images have already started to come in.

At higher inclinations, Cassini can also obtain excellent views of Saturn’s poles, and measure Saturn’s atmosphere at higher latitudes via occultation observations, where radio signals, sunlight or starlight received after passing through the atmosphere help to determine its composition and density.

The “how” is by using the gravity of Titan — Saturn’s largest moon by far — to change the spacecraft’s trajectory. Like the rings and Cassini’s previous orbit, Titan revolves around Saturn within a plane very close to Saturn’s equatorial plane. As Cassini flies past Titan, Titan’s gravity bends the spacecraft’s path by pulling it towards the moon’s center — similar to a ball bearing rolling on a smooth horizontal surface past a magnet. Near Titan, the motion is confined to a plane containing the spacecraft’s path and Titan’s center of mass. If this “local” plane coincides with Cassini’s orbital plane about Saturn, the trajectory’s inclination will remain unchanged. However, if this plane differs from Cassini’s orbital plane about Saturn, then the bending from Titan’s gravity will have a component out of Cassini’s orbital plane with Saturn, and this will change the tilt of the spacecraft’s orbit. Repeated Titan flybys will raise Cassini’s orbit inclination to nearly 62 degrees by April of next year and then lower it back to the Saturn equatorial plane in March 2015.

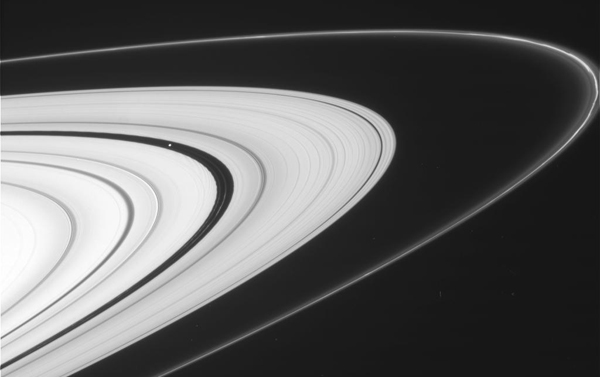

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has recently resumed the kind of orbits that allow for spectacular views of Saturn’s rings. This view, from Cassini’s imaging camera, shows the outer A ring and the F ring. The wide gap in the image is the Encke gap, where you see not only the embedded moon Pan but also several kinky, dusty ringlets. A wavy pattern on the inner edge of the Encke gap downstream from Pan and a spiral pattern moving inwards from that edge show Pan’s gravitational influence. The narrow gap close to the outer edge is the Keeler gap. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has recently resumed the kind of orbits that allow for spectacular views of Saturn’s rings. This view, from Cassini’s imaging camera, shows the outer A ring and the F ring. The wide gap in the image is the Encke gap, where you see not only the embedded moon Pan but also several kinky, dusty ringlets. A wavy pattern on the inner edge of the Encke gap downstream from Pan and a spiral pattern moving inwards from that edge show Pan’s gravitational influence. The narrow gap close to the outer edge is the Keeler gap. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSIGravity assists are key to Cassini’s ever-changing orbital geometries. Onboard propellant alone would quickly become depleted attempting to accomplish these same changes. A gravity assist can be characterized by the amount of “delta-v,” or change in the velocity vector, it imparts to a spacecraft. Delta-v may of course also be imparted to the spacecraft via rocket engines and, either way, alters the spacecraft’s orbit. The eight Titan gravity assists responsible for raising Cassini’s inclination to 62 degrees will provide a delta-v of 15,000 mph (6.6 kilometers per second). For comparison, Cassini’s rocket engines had only enough propellant after initially achieving orbit around Saturn to deliver about 2,700 mph (1.2 kilometers per second) of delta-v. That’s 15,000 mph of capability spread over 11 months via gravity assists versus a modest 2,700 mph of capability spread over more than 13 years via rocket engines! Because delta-v is a vector, it may change both the speed and direction of Cassini at a point along its orbit, so the speed of Cassini is not changing by 15,000 mph, but mostly all of the directional changes sum to 15,000 mph. To give these values some context, Cassini’s speed typically varies between as low as 2,500 mph (1.1 kilometers per second) and as high as 79,000 mph (35 kilometers per second) relative to Saturn between apokrone and perikrone, the farthest and closest points from Saturn along its orbit. Gravity assists from the initial prime mission Titan flyby in 2004 to the final Solstice Mission Titan flyby in 2017 will provide nearly 200,000 mph (90 kilometers per second) of delta-v, leveraging the onboard propellant by a ratio of 75 to 1. The bulk of the Saturn tour trajectory is shaped by gravity assists, while the role of onboard propellant is to fine-tune the trajectory.

At the end of year 2015, Cassini will again begin climbing out of Saturn’s equatorial plane in preparation for its grand finale. After reaching an inclination of nearly 64 degrees, a Titan gravity assist in April 2017 will change Cassini’s perikrone so that Cassini will pass through the narrow 2,000-mile (3,000-kilometer) gap between Saturn’s atmosphere and innermost ring. Twenty-two spectacular orbits later, one final distant Titan gravity assist will alter Cassini’s course for a fiery entry into Saturn’s atmosphere to end the mission.