HHS Action Plan to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections: Influenza Vaccination of Healthcare Personnel

I. Introduction

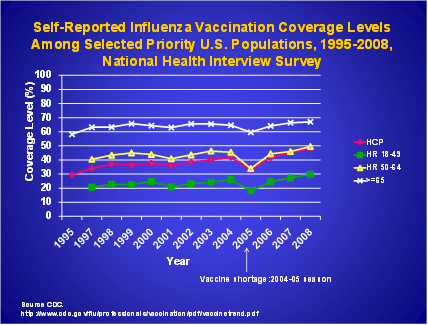

Influenza transmission to patients by healthcare personnel (HCP) is well documented.1-8 HCP can acquire and transmit influenza from patients or transmit influenza to patients and other staff. Vaccination remains the single most effective preventive measure available against influenza, and can prevent many illnesses, deaths, and losses in productivity. Despite the documented benefits of HCP influenza vaccination on patient outcomes,9,10 HCP absenteeism,11 and on reducing influenza infection among staff, vaccination coverage among HCP has remained well below the national 2010 health objective of 60%.12 (Figure 1) While preliminary data suggest 62% of HCP reported receiving seasonal influenza vaccine in 2009, only 37% reported receiving the pandemic A/H1N1 vaccine.13

FIGURE 1.

A goal of 90% coverage has been proposed to be included in Healthy People 2020 for HCP influenza vaccination. Several challenges lie ahead in meeting this high target. To identify and implement areas of strategic focus to increase immunization coverage of HCP, and to provide direction for future Departmental resources in this initiative with an overall goal of increasing influenza vaccination coverage among HCP, a federal work group, the Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs) Increasing Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Healthcare Personnel Working Group has been convened. The group proposes a goal of 70% vaccination coverage by 2015. Because most HCP provide care to, or are in frequent contact with, patients at high risk for complications of influenza, HCP are a high priority for expanding vaccine use. Achieving and sustaining high vaccination coverage among HCP will protect staff and their patients and reduce disease burden and healthcare costs.

II. Background

A. Definition of Healthcare Personnel

The term healthcare personnel is broadly defined as all paid and unpaid persons working in healthcare settings who have the potential for exposure to infectious materials.[i] The settings for HCP include acute care hospitals, long-term care facilities, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centers, physician’s offices, urgent care centers, outpatient clinics, home health agencies, and emergency medical services. Thus HCP includes a range of those directly, indirectly, and not involved in patient care who have the potential for transmitting influenza to patients, other HCP, and others.

B. Influenza Morbidity, Mortality, and Costs

The morbidity, mortality, and economic impact from influenza each year can be substantial as the following U.S. statistics demonstrate:

- Each year, between 5% and 20% of the population becomes ill with influenza;14

- Between 1976 and 2007, between 3,349 and 48,614 influenza-associated deaths occurred each year;15

- More than 200,000 hospitalizations due to influenza occurred each year between 1979 and 2001;16

- Annual influenza epidemics contribute to 610,660 life-years lost, 3.1 million days of hospitalization, and 31.4 million outpatient visits; 17

- Rates of serious illness and death resulting from influenza and its complications are increased in high-risk populations, such a those over 50 years or under four years of age, and persons of any age who have underlying conditions that put them at an increased risk.18

C. Influenza Among HCP

Several studies have documented serologic evidence of influenza infection after a mild influenza season. One study showed that among 23% of HCP with serologic evidence of influenza infection, 59% did not remember having influenza, and 28% could not recall any respiratory infection, suggesting a high proportion of asymptomatic illness.19 Thus, HCP who are clinically or sub-clinically infected can transmit influenza virus to other persons at high risk for complications from influenza.

D. Transmission of Influenza in Healthcare Settings

Higher vaccination coverage among HCP has been associated with a lower incidence of nosocomial influenza cases.20 Studies have shown when staff vaccination coverage increases, the proportion of laboratory-confirmed cases of influenza occurring among HCP decreases.21,22 In addition, the proportion of nosocomial cases among hospitalized patients decreases as well, suggesting that increased staff vaccination can contribute to the decline in the number of nosocomial influenza cases.

E. Influenza Vaccine Oversight

Preparing for the influenza season each year is a time-critical, highly orchestrated, collaborative effort between the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), the World Health Organization (WHO), vaccine manufacturers, and the health community. It is a year-round process that requires ongoing worldwide influenza disease surveillance, development of recommendations for immunization, selection of virus strains, and the manufacture and distribution of new vaccine.

Influenza Virus

Influenza viruses are single-stranded, helically shaped RNA viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae. The viruses can be divided into three types: A, B, and C. Type A influenza A has subtypes that are determined by the surface antigens hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Three types of hemagglutinin in humans (H1, H2, and H3) have a role in virus attachment. Two types of neuraminidase (N1 and N2) have a role in virus penetration into cells.

Type A influenza causes moderate to severe illness in all age groups and infects humans and other animals. Type B influenza causes milder disease, primarily affects children, and infects only humans. Type C influenza is rarely reported as a cause of human illness and has not been associated with any epidemics.

The nomenclature to describe the type of influenza virus is expressed in the following order: 1) virus type, 2) geographic site where it was first isolated, 3) strain number, 4) year of isolation, and 5) virus subtype.

Because seasonal influenza is dominantly caused by two types of influenza virus, (influenza A and B), and two subtypes of influenza A, A/H1N1, and A/H3N2, the vaccine includes a representative strain of the two A subtypes and a B virus. With the input of its Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, FDA selects the viral strains to be used in the annual trivalent influenza vaccines. Because the influenza virus mutates, each year's vaccine virus strains are usually different from the preceding year. The manufacturing demands are tremendous because there is no other instance in which a new vaccine is manufactured de novo every year. Influenza vaccines undergo the FDA review process for approval, which includes stringent manufacturing and quality oversight processes.

The FDA has licensed two forms of influenza vaccine for use in the United States: the inactivated vaccine (sometimes called the "flu shot") and the live attenuated vaccine (nasal spray). The inactivated vaccine contains inactivated, or killed, virus and is given with a needle in the arm. The nasal spray vaccine contains live viruses that are weakened, or attenuated, and is administered into the nose with a nasal sprayer. Neither vaccine causes influenza. CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) provides annual recommendations for the prevention and control of influenza, including use of vaccines.

F. Effectiveness and Safety of Influenza Vaccine

FDA regulates vaccines for use in the United States; the agency is responsible for evaluating their safety and effectiveness, and whether they meet statutory and regulatory standards for licensure and use in the United States. Working to ensure an adequate, safe, and effective supply of influenza vaccine each year is one of the FDA's highest priorities.

In some cases vaccines and circulating viruses are not always an exact or even optimal match. Although a less-than-ideal virus match between the viruses in the vaccine and those in the circulating viruses can reduce vaccine effectiveness, it is known from studies that the vaccine can still provide enough protection to make illness milder or prevent flu-related complications.

Studies have shown that the inactivated influenza vaccine (administered as an injection), is 70% to 90% effective in healthy adults younger than 65 years of age when it is closely matched to the circulating virus strains. Even during influenza seasons during which the vaccine does not exactly match the circulating strain, studies have shown that the vaccine still may have protective effects and result in milder illness and/or can prevent flu-related complications. Vaccination in individuals 65 years of age and older reduces the likelihood of hospitalization for influenza-related complications by 30% to 70%. And for those living in nursing homes or other long-term care facilities, the vaccine can be up to 80% effective in preventing death from influenza. Vaccination can also save healthcare dollars by decreasing workforce absenteeism and use of healthcare resources.16,23

The most common side effects associated with the inactivated influenza vaccine, administered as an injection, include soreness, redness, tenderness, and swelling at the injection site. These reactions are transient, generally lasting one to two days. Local reactions are reported in 15% to 20% of vaccines. Fever, malaise, allergic, and neurologic reactions occur rarely.

The live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), administered as a nasal spray, is recommended for healthy, non-pregnant adults younger than 50 years of age. The most common side effects reported include cough, runny nose, nasal congestion, sore throat, and chills. No serious adverse reactions have been identified in LAIV recipients.

G. Cost-Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccination

Influenza vaccination of adults has been shown to be cost-effective by reducing both direct medical costs and indirect costs from absenteeism. Several studies demonstrated that the vaccination of adults aged less than 65 years resulted in between 13% and 44% fewer healthcare provider visits, 18% and 45% fewer lost workdays, 18% and 28% fewer days working with reduced effectiveness, and a 25% decrease in antibiotic use.24,25,26

III. Addressing HCP Vaccination Rates

Despite an increase in influenza vaccination coverage rates beginning in the early 1990s, HCP influenza vaccination coverage remained well below the HP 2010 goal of 60% until 2009-2010, when coverage with seasonal influenza vaccine was estimated at 62%.13

A. Factors Influencing HCP Vaccination

Reported reasons for, and barriers to, HCP acceptance of influenza vaccinations include the following: 27,28,29

Reasons HCP accept the influenza vaccination:

- Desire for self-protection;

- Desire to protect patients;

- Desire to protect family members;

- Previous receipt of influenza vaccine;

- Perceived effectiveness of the vaccine;

- Desire to avoid missing work;

- Peer recommendation;

- Personal physician recommendation;

- Strong worksite recommendation;

- Had influenza previously;

- Belief that receiving the vaccine is a professional responsibility;

- Access to vaccination/coverage;

- Vaccinations provided free of charge; and,

- Belief that the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risk of side effects.

Reasons HCP decline the influenza vaccination:

- Fear of contracting influenza/influenza-like illness from the vaccine;

- Fear of vaccine side effects;

- Perceived ineffectiveness of the vaccine;

- Perceived low or no likelihood of developing influenza;

- Fear of needles;

- Insufficient time, inconvenience, or forgetting to get the vaccination;

- Reliance on homeopathic treatments;

- Belief that their own host defenses would prevent influenza;

- Lack of physician recommendation;

- Belief that other preventive measures would minimize or eliminate influenza risk;

- Belief that influenza is not a serious disease;

- Lack of free vaccinations; and,

- Belief that the vaccine is not necessary for individuals younger than 65 years of age.

B. Strategies for Improving HCP Vaccination Rates

Facilities that employ HCP should use evidence-based approaches to maximize vaccination rates. In general, multi-component interventions are shown to be the most effective. The following strategies are recommended by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) and ACIP.30,31,32,33

Education and Campaigns

- Educational programs that emphasize the benefits of HCP vaccination for staff and patients; and,

- Organized campaigns that promote and make the vaccine accessible.

Role Models

- Vaccination of senior medical staff, hospital executives, or opinion leaders.

Improved Access

- Making vaccine readily available at congregate areas (e.g., clinics), during conferences, or use of mobile carts;

- Provision of incentives; and,

- Provision of vaccine at no charge.

Measurement and Feedback

- Posting of vaccination coverage levels in different areas of a healthcare facility;

- Monitoring vaccination coverage by facility area (e.g., ward or unit) or occupational group;

- Use of HCP influenza vaccination coverage as a healthcare quality measure in states that mandate public reporting of HAIs; and,

- Use of signed declination statements from HCP who refuse vaccination.

Legislation and Regulation

- Legislative and regulatory efforts have favorably affected hepatitis B vaccination rates among HCP and can be useful for increasing influenza vaccination rates among HCP;

- Four states (Maine, South Carolina, Rhode Island, and Tennessee) have “offer” laws for influenza vaccination of HCP, meaning that requirements for vaccine administration are optional[ii];

- Three states (Alabama, California, and New Hampshire) have “ensure” laws for influenza vaccination administration of HCP meaning that vaccination of non-immune persons is mandatory in the absence of a specified exemption or refusal; ii and,

- Additionally, numerous hospitals and other healthcare facilities have enacted mandatory influenza vaccination for their HCP and several report a significant increase in influenza vaccination coverage rates.[iii]

The HAI Increasing Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Healthcare Personnel Working Group was formed in 2009 to address the less than optimal immunization coverage rates among HCP. The goals of the group are:

- Develop, synthesize, and/or enhance evidence and tools for improving influenza vaccination of HCP;

- Enroll stakeholders in the initiative; and,

- Enhance and/or develop quality standards for influenza vaccination of HCP.

By implementing the goals and the inaugural project discussed later in this module, the working group aims to not only increase awareness of the importance of influenza vaccination for HCP and patients, but also to make progress toward meeting the proposed national Healthy People 2020 objective of 90% influenza vaccination coverage for all HCP.

IV. Measurement of Influenza Vaccination among Healthcare Personnel

ACIP and HICPAC recommend that healthcare facilities regularly monitor vaccination coverage and provide feedback on unit-specific or occupation-specific rates to staff and administration. In addition to monitoring vaccination coverage at the healthcare facility level, measurement of influenza vaccination coverage can be used to assess progress towards meeting national objectives.

Currently the “gold standard” for assessing influenza vaccination coverage among healthcare personnel is the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). The NHIS – a nationally representative survey of the civilian non-institutionalized household population of the United States conducted throughout the year from January through December – uses in-person interviews to collect information on health and healthcare for all eligible members of the sampled households. Information on adult vaccinations is self-reported by one randomly sampled adult within a family, except in rare cases when the selected adult is physically or mentally incapable of responding. Results from the in-person interviews are published annually in the National Center for Health Statistics Health E-Stat.[iv] During the 2009-2010 influenza vaccination campaign, CDC surveyed HCP to assess influenza vaccination coverage, using a nationally representative internet panel of HCP. Interim results from these surveys were published in the April 2, 2010 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) weekly report.13 Two national sample surveys of healthcare personnel are planned to supplement NHIS data for the 2010-2011 influenza season.

Another system that has the potential to collect influenza vaccination coverage of healthcare personnel is CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). In September 2009, CDC released the Healthcare Personnel Safety (HPS) Component within its web-based surveillance system, NHSN. The HPS Component complements the Patient Safety and Biovigilance components that are already available in NHSN. The HPS Component replaced CDC’s National Surveillance System for Health Care Workers (NaSH) legacy system and is comprised of two modules: the Blood and Body Fluid Exposure and Management Module and the Influenza Vaccination and Management Module. Currently, participation in either module is voluntary. The modules feature basic, custom, and advanced analysis capabilities available in real-time, which allows facilities to compile and analyze their own data, as well as benchmark these results to aggregate NHSN estimates. The HPS Component can assist participating facilities in developing surveillance and analysis capabilities to permit the timely recognition of healthcare personnel safety problems and prompt interventions with appropriate measures.

Influenza vaccination data submitted to CDC will ultimately capture regional trends on the yearly uptake of the vaccine, prophylaxis and treatment for healthcare personnel, as well as the elements within yearly influenza campaigns that succeed or require improvement. Data may be further stratified by occupational groups, or facility type and size. At the state and national levels, NHSN’s HPS component will aid in monitoring rates and trends, identifying emerging hazards for healthcare personnel, assessing risk of occupational infection, and evaluating preventive measures, (e.g., use of engineering controls, work practices, protective equipment, post-exposure prophylaxis, and immunization uptake strategies).

The current Influenza Vaccination Module may soon offer options for healthcare facilities to submit vaccination summary data. NHSN will partner with vendor-based surveillance systems to permit periodic data extractions into NHSN.

V. Coordination of Efforts: Interagency Working Group

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is strategically positioned to catalyze multi-agency integration efforts and foster close collaboration with other public entities and private sector organizations that have a stake in increasing influenza immunization of HCP. This work depends on agency-wide collaborations which will be supported by this group. Representatives from CDC, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH) in the Office of the Secretary, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), FDA, NIH, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) serve as members of this group. Aligning data collection systems that track immunization rates across agencies and collaborating across agencies to identify a strategic communications strategy will continue to be priorities for this group. Initial surveys of ongoing efforts across HHS agencies allowed the working group to identify initial focus areas described below.

VI. Work Group Goals and Tasks

A. Develop, Synthesize and/or Enhance Evidence and Tools for Improving Influenza Vaccination of HCP

The rationale and evidence for the importance of influenza vaccination of HCP has been described throughout this module. Beyond causing significant illness among HCP themselves, HCP can transmit influenza to their patients quickly and efficiently due to the high volume of patient encounters, many of whom are also in at-risk populations. Influenza vaccination can prevent much of HCP illness, absenteeism, and transmission and has been shown by numerous studies to be cost-effective.17,19,34 There are many successful strategies for implementing influenza vaccination programs for HCP, as previously described. Toolkits can provide convenient compilations of these rationales and strategies, and provide posters and other materials to implement HCP influenza vaccination programs. Some of these include:

- The HHS toolkit;[v]

- American Medical Directors Association toolkit “Immunizations in the Long Term Care Setting;[vi]

- Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) “Protect your Patients, Protect Yourself”;[vii]

- The Joint Commission’s monograph, “Providing a Safer Environment for Health Care Personnel and Patients through Influenza Vaccination: Strategies from Research and Practice";[viii] and,

- And many others described by the National Influenza Vaccine Summit.[ix]

To assure the most recent data and resources are available for HCP and their supervisors for the implementation of influenza vaccination programs, the working group will execute the tasks below.

Work Group Tasks:

- Review available evidence for vaccination benefits, including improved health outcomes for HCP and patients. Weigh benefits against costs and any possible harms. Identify the patient populations at highest risk of influenza-related mortality (e.g. infants, older persons, persons with respiratory illnesses) in whom vaccination of HCP would potentially provide the greatest benefit and review evidence for balance between benefits and harms for those specific populations.

- Review available evidence on the factors that affect HCP vaccination as well as evidence-based strategies and best practices to increase vaccination rates. These include but not limited to: recommendations or policies from medical and health organizations, state laws, improving access, educational efforts, employment mandates, declination forms, etc.

- Identify gaps in current knowledge about reasons for HCP receiving and declining influenza vaccination, and approaches to fill these gaps

- Examine the potential impacts policy changes, such as mandating that influenza vaccination be offered or performed, may have on increasing influenza vaccination coverage for HCP

- Align data collection systems that track immunization rates across agencies

- Create and widely disseminate guidance, toolkits, and other materials for implementing evidence-based strategies to increase HCP vaccination rates

B. Enroll Stakeholders in the Initiative

It is important to enroll stakeholders, including healthcare-affiliated organizations, unions and collective bargaining units, in order to garner support towards the goal of increasing HCP influenza vaccination and to provide a mechanism to share best practices, as well as for the exchange of ideas and opinions.

Several professional organizations, such as the American College of Physicians (ACP),[x] the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA),[xi] and APIC[xii] have put forth policy statements recommending mandatory influenza vaccination of HCP. Many other organizations, such as the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the American Medical Association (AMA), recommend voluntary HCP vaccination. For those organizations without a policy, we would like to encourage the professional organizations to develop a written policy supporting, at a minimum, voluntary influenza vaccination of HCP.

C. Enhance and/or Develop Quality Standards for Influenza Vaccination of HCP

Currently the CDC’s HICPAC and ACIP recommend that all HCP be vaccinated against influenza on an annual basis. These guidelines, however, are not mandatory, and influenza vaccination coverage levels among HCP remain low, as previously discussed. In 2006, The Joint Commission required that hospitals and long-term care facilities seeking accreditation establish an influenza vaccination program to educate about and provide influenza vaccination to HCP. It did not, however, go so far as to require mandatory vaccination of HCP with influenza vaccine. While OSHA has a Bloodborne Pathogens standard (§1910.1030) which includes hepatitis B vaccination for HCP as part of a worker safety regulation, they do not have a comprehensive standard that addresses occupational exposure to contact, droplet, and airborne transmissible diseases. OSHA does not currently include any vaccination besides hepatitis B as part of their worker safety regulation. The recent Request for Information released by OSHA includes a section on “Vaccination and Post Exposure Prophylaxis” to explore the potential inclusion of other vaccines recommended for HCP such as influenza, MMR, varicella, Tdap, and meningococcal as part of their worker safety regulations.35

To further enhance quality standards for influenza vaccination of HCP, other steps that could be taken include encouraging The Joint Commission to:

- Extend the standards for HCP influenza vaccination to outpatient and other healthcare settings;

- Establish a performance measure for the percent of HCP vaccinated against influenza; and,

- Establish a specific percentage goal of HCP vaccinated against influenza.

Additionally, this working group has established a suggested metric for influenza vaccination of HCP in 2015, to complement the Healthy People goal of 60% HCP vaccination in 2010 and proposed goal of 90% in 2020. This working group proposes the interim metric of 70% coverage of HCP influenza vaccination in 2015.

VII. Inaugural Project

The working group will undertake an Inaugural Project that will address Goal A of the group’s objectives – to develop and/or enhance evidence and tools for improving influenza vaccination of HCP. The purpose of the project is to examine the effect that policy changes, such as mandating that influenza vaccination be offered or performed, may have on increasing influenza vaccination coverage for HCP. The intended outcome of the project is to have a comprehensive report that identifies the existing policies in each State, allowing for comparisons between States achieving higher rates of influenza vaccination of HCP, as well as comparisons to model state and federal statutes that may be useful for States drafting future legislation. Collaborations with state and local policymakers, facility leadership, workforce representatives, professional associations, and patient advocates will be an integral component of this project and will address the goal of the group to enroll stakeholders in the initiative.

The proposed project will assist States in creating a legal environment that encourages influenza vaccination of all HCP. To facilitate creating this environment, a set of educational materials will be developed and disseminated to stakeholders interested in increasing influenza vaccination coverage rates of HCP. The materials will include a common definition of “healthcare personnel,” describe the strategies that facilities have implemented to encourage voluntary vaccination, and outline the current coverage rates among HCP. The materials will also include a review of evidence-based practice of seasonal influenza vaccination of HCP as it relates to transmission of illness to patients (Goal A; Task A) and summarize the literature that addresses the relationship between vaccination of HCP and disease rates among patients.

The project will then review the legal environment surrounding requirements for influenza vaccination of HCPs, such as requirements for employers to offer vaccination to HCP, to obtain declination forms from those HCP who decline vaccination, or to mandate that vaccination be performed. Federal and state laws, individual facilities’ policies, and judicial decisions will be reviewed. Summaries of each state’s legal requirements will be prepared, which will:

- determine the essential elements for inclusion of HCP immunization in comprehensive state statutes establishing requirements for influenza vaccination of HCP;

- draft model state statute(s) taking into account variability between States and allowing for flexibility in language;

- develop tables that compare each state’s existing policies to the model statute(s);

- invite federal and state partners to review all materials, develop consensus and make recommendations;

- develop an interactive website under the aegis of HHS or one of its agencies providing the above information, and;

- provide technical assistance to policymakers upon request.

The Project’s findings will serve as the basis for developing recommendations and model language for federal and state statutes on HCP influenza immunization. The project will draft summaries of each State’s legal requirements, determine the essential elements for inclusion in comprehensive state and federal statutes, and draft model state and federal statutes.

Upon completion, the inaugural project will provide a set of model policies defining a legal environment that encourages increased uptake of influenza vaccinations among all HCP.

VIII. Challenges and Opportunities

The primary challenge the working group faces is how best to work with partners to substantially increase influenza vaccination coverage rates among HCP when, after many years of interventions, the coverage rate has barely exceeded the national Healthy People 2010 goal of 60%. This will become an even greater challenge if the proposed national goal for 2020 of 90% is adopted.

Additionally, rates of vaccination vary across settings and groups. For example, estimated vaccination coverage among physicians and nurses was above 60% in 2009-2010, while coverage among all other types of HCP was less than 50%. Coverage among HCP working in hospitals was over 60%, while for those HCP in long term care facilities coverage is well below 50%.36 Healthcare settings should tailor their strategies to their setting, workforce, and region.

Finally, the definition of HCP is still not standardized in all settings, allowing variations for whom influenza vaccine is mandated, recommended, or provided in different settings and even institutions within those settings.A major opportunity for improvement in vaccination coverage can be achieved through a standardized, comprehensive measurement system. Several organizations such as the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, The Joint Commission, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, and HICPAC have all recommended measurement of vaccination rates as an important component of healthcare facility influenza vaccination programs.17,18,37

However implementing such a system presents several challenges. A recent study conducted by Lindley et al.38 found substantial variation in measurement practices among hospitals surveyed. They found that more than one-third of hospitals in their study did not include certain groups, such as contract staff, attending physicians, volunteers, students, and residents, in their influenza vaccination coverage measurements, although all of these groups are included in the ACIP/HICPAC definition of HCP. A standard definition of which groups should be included when assessing influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare facilities will facilitate comparisons between different types of healthcare facilities.

An opportunity to address this challenge is the National Quality Forum’s (NQF’s) time-limited endorsement of an HCP influenza vaccination coverage measure.39 The measure specifies that information to be collected on influenza vaccination received at a facility and elsewhere for paid and unpaid persons working in healthcare settings, and that vaccine declination and contraindications to vaccination be measured and reported separately. The time-limited NQF-endorsed measured will be pilot tested in four locations for the 2010-2011 influenza season.

References

- Malavaud S, Malavaud B, Sanders K, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of influenza virus A (H3N2) infection in a solid organ transplant department. Transplantation 2001; 72:535-537.

- Maltezou HC, Drancourt M. Nosocomial influenza in children. Journal of Hospital Infection 2003; 55:83-91.

- Weinstock DM, Eagan J, Malak SA, et al. Control of influenza A on a bone marrow transplant unit. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2000; 21:730-732.

- Cunney FJ, Bialachowski A, Thornley D, Smaill FM, Pennie RA. An outbreak of influenza A in a neonatal intensive care unit. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2000; 21:449-454.

- Hall CB, Douglas RG Jr. Nosocomial influenza infection as a cause of intercurrent fevers in infants. Pediatrics 1975; 55:673-677.

- Salgado CD, Farr BM, Hall KK, Hayden FG. Influenza in the acute hospital setting. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2002; 2:145-155.

- Kapila R, Lintz DI, Tecson FT, Ziskin L, Louria DB. A nosocomial outbreak of influenza A. Chest 1977; 71:576-579.

- Sartor C, Zandotti C, Romain F, et al. Disruption of services in an internal medicine unit due to nosocomial influenza outbreak. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2002; 23:615-619.

- Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA 2004; 292:1333-1340.

- Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA 2003; 289:179-186.

- Molinari NM, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, et al. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine 2007; 25:5086-5096,

- Walker FJ, Singleton JA, Lu P, Wooten KG, Strikas RA. Influenza vaccination of healthcare workers in the United States, 1989-2002. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2006; 27:257-265.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim results: Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 and Monovalent Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Health-Care Personnel—United States August 2009- January 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Recommendations and Report 2010; 59:357-362. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5912a1.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Seasonal Influenza Vaccination for Health Professionals 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/index.htm

- Centers for Disease Control. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza—United States, 1976—2007. MMWR 2010;59:1057-62. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5933a1.htm?s_cid=mm5933a1_w

- Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA 2004;292:1333--40.

- Pearson ML., Bridges CB, Harper SA: Influenza vaccination of health-care personnel: Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Recommendations and Report 2006; 55:1-16. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5502a1.htm

- Fiore AE, Uyeki T, Broder K, Finelli L, Euler G, et al. Prevention & Control of Influenza with Vaccines - Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) 2010. MMWR 2010 Aug 6; 59(RR08):1-62.

- Wilde JA, McMillan JA, Serwint J, Butta J, O’Riordan MA, Steinhoff MC. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine in health care professionals: a randomized trial. JAMA 1999; 281:908-913.

- Salgado CD, Giannetta ET, Hayden FG, Farr BM. Preventing influenza by improving the vaccine acceptance rate of clinicians. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2004; 25: 923-928.

- Potter J, Stott DJ, Roberts MA, et al. Influenza vaccination of health-care workers in long-term-care hospitals reduces the mortality of elderly patients. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1997; 175:1-6.

- Hayward AC, Harling R, Wetten S, et al. Effectiveness of an influenza vaccine programme for care home staff to prevent death, morbidity, and health service use among residents: cluster randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 2006; 333:1241-1246.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness: Questions and Answers for Health Professionals. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/effectivenessqa.htm

- Bridges CB, Thompson WW, Meltzer MI, et al. Effectiveness and cost-benefit of influenza vaccination of healthy working adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000; 284:1655-1663.

- Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Rivetti D, Deeks J. Prevention of early treatment of influenza in healthy adults. Vaccine 2000; 18:957-1030.

- Campbell DS, Rumley MH. Cost-effectiveness of the influenza vaccine in a healthy, working-age population. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 1997; 39: 408-414.

- Lester RT, McGeer A, Tomlinson G, Detsky AS. Use of, effectiveness of, and attitudes regarding influenza vaccine among house staff. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2003; 24:839-844.

- Clark SJ, Cowan AE, Wortley PM. Influenza vaccination attitudes and practices among US registered nurses. American Journal of Infection Control 2009; 37: 551-556.

- Hollmeyer HG, Hayden F, Poland G, Bucholz U. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospitals—a review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine 2009; 19: 3935-3944.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza vaccination of health-care personnel: recommendations of the Health-Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2006; 55:1-16. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5502.pdf

- Babcock HM, Gemeinhart N, Jones M, Dunagan WC, Woeltje KF. Mandatory influenza vaccination of health care workers: translating policy into practice. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2010; 50:459-464.

- Ribner BS, Hall C, Steinberg JP, Bornstein WA, et al. Use of mandatory declination form in a program for influenza vaccination of healthcare workers. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2008; 29:302-308.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State immunization laws for healthcare workers and patients. Available at: http://www2a.cdc.gov/nip/StateVaccApp/statevaccsApp/default.asp Accessed April 12, 2010.

- Talbot TR, et al: SHEA position paper: Influenza vaccination of healthcare workers and vaccine allocation for healthcare workers during vaccine shortages. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2005; 26:882-890.

- Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Infectious diseases: request for information. Federal Register 75(87): 24835-24844. May 6, 2010. Available at: http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=FEDERAL_REGISTER&p_id=21497

- Strikas R, Euler G, Singleton J. Disparities in influenza vaccination rates among healthcare personnel, United States, 2007-08. March 22, 2010. Fifth Decennial International Conference on Healthcare-associated Infections, Atlanta, Georgia.

- Improving influenza vaccination rates in health care workers: strategies to increase protection for workers and patients. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases 2004. Available at: http://www.nfid.org/pdf/publications/hcwmonograph.pdf

- Lindley MC, Yonek J, Ahmed F, Perz JF, Torres GW. Measurement of Influenza Vaccination Coverage among Healthcare Personnel in US Hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 30(12): 150-157

- National Quality Forum. National voluntary consensus standards on influenza and pneumococcal vaccination. December, 2008. Available at http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2008/12/National_Voluntary_Consensus_Standards_for_Influenza_and_Pneumococcal_Immunizations.aspx

[i]Definition of Health Care Personnel (HCP), March 2008*

HCP refers to all paid and unpaid persons working in health-care settings who have the potential for exposure to patients and/or to infectious materials, including body substances, contaminated medical supplies and equipment, contaminated environmental surfaces, or contaminated air.

HCP might include (but are not limited to) physicians, nurses, nursing assistants, therapists, technicians, emergency medical service personnel, dental personnel, pharmacists, laboratory personnel, autopsy personnel, students and trainees, contractual staff not employed by the health-care facility, and persons (e.g., clerical, dietary, house-keeping, laundry, security, maintenance, billing, and volunteers) not directly involved in patient care but potentially exposed to infectious agents that can be transmitted to and from HCP and patients.

These recommendations apply to HCP in acute care hospitals, nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, physician’s offices, urgent care centers, and outpatient clinics, and to persons who provide home health care and emergency medical services.