| |

|||

|

|

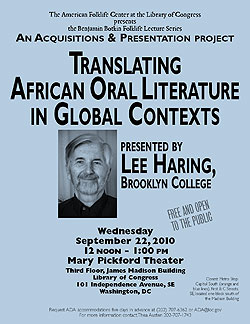

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress September 22, 2010 Event Flyer Translating African Oral Literature in Global ContextsPresented by Lee Haring

The German theologian and philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) saw the essential problem in translating. He argued that there are only two methods: "Either the translator leaves the author in peace, as much as possible, and moves the reader towards him, or he leaves the reader in peace, as much as possible, and moves the author towards him." Schleiermacher didn't foresee a world in which UNESCO would pass a Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, and thereby create a cultural vacuum, which translation would have to fill. Up to now, much translation has politely brought Africa to the world, leaving it in peace. Are there ethical implications to that? Like all translation, the translating of African art and literature is an ethical and political act. Henri Meschonnic, the French poet and Bible translator, has repeatedly declared, "There is an ethics of translation, there is a politics of translation." The translation of Africa's Intangible Cultural Heritage — which is nothing but an uptown term for Folklore — requires transmitting information about communications which are situated in social interaction. To translate African folklore, therefore, is to ask your reader to enter an alien system. One alternative is to leave readers in peace, relatively anyway, and bring them great novels, like Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart, that teach them about folkloric communication. Another alternative is to examine the translation practices of Africans and use them as a model for translating Africa in global contexts. For about thirty-five years, I have been translating materials derived from Africa: folktales, proverbs, riddles, and other verbal art, from five island groups — Madagascar, Mauritius, Réunion, Seychelles, and the Comoros. These islands lie east of the continent, in the Southwest Indian Ocean. They are not much known in the English-speaking world, and their historical and cultural connection to Africa is obscure to most of their citizens. By examining their verbal arts — comparing, for example, folktales from the island of Mauritius with cognate folktales from Mozambique and Malawi, from which African slaves were imported to Mauritius — we see the great cultural debt the islands owe to Africa. I have given an account of this debt, and translated a hundred of the stories, in my book Stars and Keys. A strong component of the debt is a capacity, developed in Africa and carried by Africans to the islands, for remembering, borrowing, and remodeling cultural patterns. In our time, this capacity is being developed by the millions around the world who have been forced, by natural disaster, war, and theft of their land, into unwanted contact with people of different languages and cultures. Their cultural plight is not much different from that of previous generations of African slaves in the Southwest Indian Ocean islands. In such points of cultural contact, pidgin and creole languages are created, and proverbs, riddles, and tales play on linguistic differences. Analogously, in cultures dominated by writing and electronic communication, parodies, jokes, and secular rituals are continually invented, and their genres continually invite new performances. This process is cultural creolization. The anthropologist Daniel Crowley observed in Trinidad what is happening in the globalizing world. Where groups bearing contrastive linguistic and cultural traditions are forced into sustained contact, he wrote, they quickly come to "know something of the other groups, and many members are as proficient in the cultural activities of other groups as of their own." Cultural creolization took place in Africa long before the inception of the world economic system, long before Paul Simon collaborated with African musicians. Now we see it everywhere, epitomizing the world's artistic production. African oral literature, because it is performed, offers the finest data available for translation studies, as well as for related problems such as metaphor, orality, and locality. Cognitive scientists are confirming that metaphor is essential to all thought, and Africanist scholars are showing all African oral genres to be animated by metaphor. These developments have implications on the theory and practice of translation. Orality and literacy, too, resonate deeply with translation: studies are showing that orality and literacy can no longer be conceived as set apart from each other, that a written transcription in the language of the speaker is already a translation. A second translation occurs when the words are put into another language, a "world language," if you believe that such things exist. Local languages in Africa are in competition not only with other local languages, but also with the languages of colonial powers. This sociocultural-political problem will be resolved when the world begins to see both a local and an international language as having their uses. Translating Africa in global contexts means learning from Africa how to renegotiate culture. It means leaving neither the reader nor the African storyteller in peace, but effecting a mediation between them. The maturing and deepening of both translation studies and folkloristics promises much for preserving and translating intangible cultural heritage, or folklore. Lee Haring

|

| ||||

The American Folklife Center was created by Congress in 1976 and placed at the Library of Congress to "preserve and present American Folklife" through programs of research, documentation, archival preservation, reference service, live performance, exhibition, public programs, and training. The Center includes the American Folklife Center Archive of folk culture, which was established in 1928 and is now one of the largest collections of ethnographic material from the United States and around the world.

The American Folklife Center was created by Congress in 1976 and placed at the Library of Congress to "preserve and present American Folklife" through programs of research, documentation, archival preservation, reference service, live performance, exhibition, public programs, and training. The Center includes the American Folklife Center Archive of folk culture, which was established in 1928 and is now one of the largest collections of ethnographic material from the United States and around the world.