|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| The Folk Archive contains documentation of a number of traditional quilters from North Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, and other states, as well as documentation from the Lands' End All-American Quilt Contest (from 1992, 1994, and 1996). |

| Materials related to quilts from both these collections are available online in the American memory presentation Quilts and Quiltmaking in America. |

During the first half of the twentieth century, folklorists tended to confine their studies to (1) orally transmitted lore — especially songs, stories, legends, proverbs, and riddles — (2) certain customary traditions, such as rituals and festivals, and (3) traditions related to belief systems — luck, weather prediction, divination, and the like. Often neglected was the whole realm of human activity concerned with “craft,” the traditional aspects of how objects are made and used.

Influenced by cultural anthropologists, cultural geographers, and European ethnologists, all of whom regularly included objects and the human activities and beliefs associated with them as elements of their studies, folklorists gradually came to accept what has come to be known as “material culture” as an equally valid area for documentation and analysis. Since the 1960s, American folklorists have been energetic in their studies of material culture.

American folklore studies of material culture typically address how objects are designed, made, and used, and what they mean (on various levels) to those who make and use them. Folklorists are also interested in the objects themselves, and in such matters as their shapes and dimensions, the materials from which they are made, their decorative elements, and the variations between different makers and groups, as well as variations over time and place.

Houses, barns, and other traditional buildings constitute a subcategory of material culture known as vernacular architecture. Other objects of interest include baskets, boats, clothing, furniture, metalwork, pottery, and quilts. In general, folklore studies of material culture have favored handmade objects such as these, and craftsmanship itself has been a special focus.

|

| In 1971, Howard Finster began to build and plant a garden in the two-acre yard behind his home in Summerville, Georgia, inspired by a vision instructing him to "build a paradise and decorate it with the Bible." In 1976, a similar vision prompted him to paint "sacred art," which he proceeded to do, applying to wood or metal the tractor enamel he used in his bicycle repair business. Over his lifetime, Howard Finster, "man of visions," as he called himself, worked at many occupations and trades, including farmer, textile factory worker, sawmill laborer, and bicycle repairman. He began to preach at the age of sixteen and was eventually ordained at Violet Hill Baptist Church, in Valley Head, Alabama. He traveled from church to church, in Alabama and Georgia, until he settled at the Chelsea Baptist Church, in Menlo, Georgia. Finster is typical of many such folk or visionary artists who create fantastical sculptures and paintings, often using objects from everyday life. Finster is unusual in that he became widely known, and came to have his paintings sold at art galleries in New York and other major cities. The American Folklife Center became acquainted with the Reverend Howard Finster during a field project in south-central Georgia in 1977, and eventually commissioned Finster to paint several paintings, including He Could Not Be Hid. |

The Archive of Folk Culture has many collections that document material culture. The Blue Ridge Parkway Folklife Project Collection (1978) includes documentation of the quilting tradition carried on in rural communities along the Virginia-North Carolina border. The Paradise Valley Folklife Project Collection (1978 – 82) includes documentation of numerous objects integral to the rancher’s life in northern Nevada, from boots to branding irons to saddles, all the way to ranch houses and barns. The Pineland’s Folklife Project Collection (1983) includes documentation of the construction and use of traditional New Jersey bird-hunting skiffs. The Grouse Creek Cultural Survey (1985) teamed folklorists with anthropologists, sociologists, architects, and city planners to investigate the relationships among architectural history, folklife, and historic preservation. The Italian-Americans in the West Project Collection (1989 – 91) includes a wealth of information about Italian-American material culture, including vernacular architecture, the traditional oven known as the forno, and various objects associated with family-run wineries. And the Maine Acadian Cultural Survey Project Collection (1991 – 92) includes painstaking documentation of barns and houses that can be used to determine the geographical extent of the Acadian cultural region.

Allied to material culture is folk art, which can be defined as the use of physical items in the production of symbolic and aesthetic works by untrained artists. Folk art takes a variety of forms: painting, sculpture, multimedia displays, and assemblages, as well as the decorative aspects of otherwise utilitarian objects. Hex signs on Pennsylvania Dutch barns, tin man sculptures made by metalworkers, front yard installations and Christmas displays, decorated school lockers, carved gun stocks, and tattoos are but a few examples of this rich vein of traditional expression.

The term folk art is somewhat problematical and has been used to encompass a variety of productions. Folklorists and the owners of art galleries have debated the definition of folk art to an uneasy truce. Gallery owners and many museum curators tend to favor folk art objects that have fine art equivalents, such as painting and sculpture. They customarily showcase the individual image and object rather than the context within which it was made. Words such as naive, self-taught, and individualistic are used to describe these objects, and the exceptional rather than the representative creation is featured. In fact, the folk artist is sometimes characterized as an outsider, visionary, or idiosyncratic, although gallery owners are loath to relinquish the magic word folk in advertising their work.

Just as everyone tells stories, knows the words to at least a few songs, celebrates holidays, and holds certain beliefs, all people practice some form of folk art. The everyday aspects of folk art would include the way people decorate the interiors of their homes or offices, their style of dress and body decoration, their flower gardens, and even their pencil doodlings and graffiti. The title of Kenneth Ames’s book on folk art, Beyond Necessity (1977), goes to the heart of how folk art might be differentiated from crafts. Where crafts speak to the needs of everyday living, folk art speaks to the emotions and beliefs and the need for aesthetic satisfaction. Yet who is to say that the world of art is any less necessary to humanity than the utilitarian world?

|

|

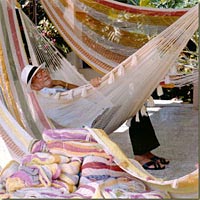

| Through the Local Legacies project, members of Congress and private individuals across the nation were involved in celebrating the Library of Congress's Bicentennial and America's richly diverse culture. For more than a year, volunteer teams documented traditional life in their local communities, including crafts, items of produce, and events such as festivals, and parades. Documentation of Puerto Rican craftsmen was submitted by Delegate Carlos Romero-Barcelo. For five hundred years, Puerto Rico has been a place of cultural fusion. This amalgamation of traditions has produced varied expressions of craftsmanship. The craft of hammock-weaving has been practiced there from the pre-Columbian era to the present José Gonzales, who learned from his parents, still uses the traditional maguey fiber to weave his hammocks. | During the Lunar New Year or Spring Festival holiday season, folk crafts are very popular among the Chinese children of Quanzhou. American Folklife Center archivist Nora Yeh has donated her extensive collection documenting traditional Chinese arts and customs, including musical performances, both Chinese and Asian American. The collection includes sound recordings, films, photographs, color slides, manuscripts, and field notes made in Taiwan, mainland China, the Philippines, Singapore, Malasia, Hong Kong, and the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. |

| More selections from the Local Legacies Project are available online in the presentation Local Legacies: Celebrating Community Roots. |

|

|

| Jersey garveys are blunt-end boats used by clammers and oystermen. Joe Reid is acknowledged locally as a master builder of these boats, which he makes and repairs. One of Reid's customers says," A garvey's just about the ugliest thing in the world, but it makes a dynamite work boat. It's a flat-bottomed boat. It's actually a working platform." | Paradise Valley is the name of both a cattle-ranching valley and a crossroads community in northern Nevada's Humbolt County, where the American Folklife Center conducted an ethnographic field research project from 1978 to 1982. The focus of the project was cattle ranching but extensive work was also done on material culture, especially vernacular architecture, and the work of immigrant Italian stonemasons. In this photo, Rusty Marshall talks with Dan and Bruno Ramasco about their family and about stonemasonry. |

|

|

| Nostalgia for their homeland may inspire immigrants to create artistic representations of distant landscapes. The outdoor mural in this photograph publicly expresses feelings shared by the community. | Vernacular architecture has been an important component of field surveys, in northern Maine, Georgia, Nevada, and along the Blue Ridge Parkway, for example, and the Folk Archive collections hold both drawings and photographs of ranch, farm, and residential buildings. |

|

|

| Joseph Delmue was born in Biasca, Switzerland, an Italian-speaking town on the Italian-Swiss border. He emigrated to Lincoln County, Nevada, in the 1870s to cut timber for the mines at Pioche. Turning to ranching in nearby Dry Valley, in the 1880s, Delmue built a substantial stone house in 1900 and a large hay barn in 1916, both buildings patterned after those in his native country. The American Folklife Center's 1900 field project Italian Americans in the West documented with photographs and drawings buildings constructed by Italian immigrants. | Known as "Robot Man" in his home town, William Clark uses the tools and skills of his trade as automotive repairman and the materials at hand in his shop to fashion robot sculptures and other artful constructions. In retirement or in their free time, workers who have developed skills in the use of materials such as wood and metal sometimes turn their hand to the creation of fanciful works of art. |

|

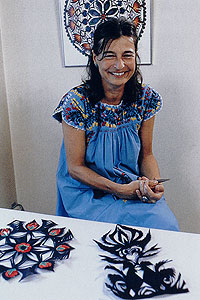

Rooster

papercut by Magdelana Gilinsky Jannotta. |

| The art of cutting paper may have originated in China. During the eighteenth century, German cutwork (scherenschnitte) and paint were combined to adorn all manner of personal messages, such as declarations of love and New Year's greetings, as well as official documents such as birth certificates and marriage licences. Papercuts called wycinanki began to appear in Poland in the mid-nineteenth century, and are still used to decorate windows, joists, and other parts of the home, particularly at Christmas and Easter. | |

( October 29, 2010 )