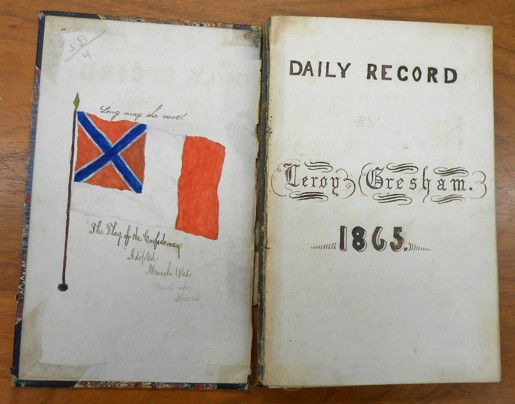

A century and a half later, LeRoy Wiley Gresham’s smudges still mark the page, in a kind of communion with students of his remarkable record of the Civil War, the collapse of the Old South, and the last years of his privileged but afflicted life.

It is a chronicle — in neat, legible handwriting — of the excitement of the war’s early months, the seeming endlessness of the conflict and the approach of the dreaded Yankees as they steamroll through Georgia.

From his rooftop, LeRoy sees the smoke and hears the booming of cannons in the distance. At night there is the glow from burning houses.

The Library of Congress is featuring selected pages of Gresham’s little-known diary as part of an extensive display of its voluminous Civil War material to mark the sesquicentennial of the war years.

The exhibit, which opens Monday, is called “The Civil War in America,” and includes more than 200 items — maps, song sheets, letters, photographs and the contents of Abraham Lincoln’s pockets the night he was assassinated.

As for Gresham’s journal, numerous Civil War diaries exist, and some are famous. Those of South Carolina belle Mary Chesnut and New York lawyer George Templeton Strong are among the best known.

But Gresham’s apparently has never been published, the library said, and it offers a unique view of the war and an intimate personal story. The library acquired it in the 1980s from family descendants.

The diary also speaks about slavery and its demise — about “servants” and “valets,” always in the background and almost always referred to by first name only, Howard, Eaveline and “Mammy Dinah.”

And it is the saga, in seven volumes, of a precocious, delicate boy who was a voracious consumer of books and newspapers, but who was often confined to a special wagon that was pulled about town by slave.

Crippled by a broken left leg years before, and tormented by what sound like bedsores, and a host of other infirmities, LeRoy is exposed to a full range of Victorian remedies — opiates, whiskey, syrup of lettuce, spirits of lavender, and various powders, plasters and poultices.

Little of it works.

From his wagon, he can only watch the other children play “town ball,” a precursor to baseball. He has to be carried at times — he weighs 63 pounds — and in one case his mother drops him. He is often despondent.

“I feel more discouraged [and] less hopeful about getting well than I ever did before,” he writes on March 17, 1863, at the age of 15. “I am weaker and more helpless than I ever was.”

And on Feb. 7, 1864: “It seems to me that as I grow older, the dreary, monotonous life I lead seems more burdensome. If I just had some regular employment I could get along better.”

Loading...

Comments