| |

|||

|

|

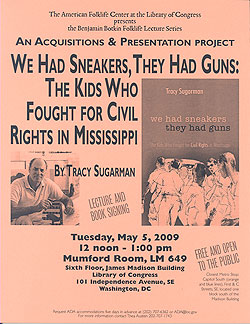

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress May 5, 2009 Event Flyer We Had Sneakers, They Had Guns:

|

|

As an illustrator and journalist, Tracy Sugarman covered the nearly one thousand student volunteers who traveled to the Mississippi Delta to assist black citizens in the South in registering to vote. One black student and two white students were slain in the struggle, many were beaten and hundreds arrested, and churches and homes were burned to the ground by the opponents of equality. Yet the example of Freedom Summer resonated across the nation. The United States Congress was finally moved to pass the civil rights legislation that enfranchised millions of black Americans. Blending oral history with memoir, We Had Sneakers, They Had Guns chronicles the sacrifices, tragedies, and triumphs of that unprecedented moment in American history.

Excerpt:

In 1964, all hell seemed to be breaking loose in the American South. The nonviolent challenge to a centuries-old racial apartheid was being answered with state-sanctioned violence, the unbridled violence of the Ku Klux Klan, and the apparent collusion of the white establishment.

For me, who had been happily documenting the wonders of postwar American industry, invention, and education, the sudden revelations of a part of my country that recalled the horrors of fascism were sickening. Like so many veterans of World War II, I believed we had vanquished fascism twenty years before. I had been making drawings and paintings that celebrated our society. How, then, could such a good and diverse people permit such atrocities? In family council, we agreed that if a way could be found for me to go to the South to do my personal reportage, I should go. Perhaps my drawings could bring a better understanding to people in the North as to what was at stake. Few white businessmen, congressmen, clergy, journalists, or professionals across Dixie raised their voices in protest when the lynchings, the beatings, the burning black churches, the poignant pleas of preachers like Martin Luther King were news in every northern paper and featured nightly on television. In our household, the images of police dogs, hoses, and the four young black children who were killed in their bombed Sunday school classroom appalled and outraged all of us. We wanted to do something, anything, that would help to stop the cruel assaults on Americans who happened to be black for our whole society. If nonviolent protests were to be destroyed by fire and bombs, the alternative was unthinkable.

In the spring of 1964, we read that the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “Snick”), an organization of young black men and women who had been inspired by the sit-ins of the early sixties, had issued a call to white students in the North to come join them in their struggle for the vote in Mississippi. Mississippi?

I could imagine Mississippi because I had read William Faulkner and Eudora Welty.

I could imagine Mississippi because every time I heard Billy Holiday singing “strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees,” I wept.

I could imagine Mississippi because I remembered the lynching of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till because he flirted with a white girl in a Delta town.

I could imagine Mississippi because on national television I watched the white man who assassinated Medgar Evers walk free and proud down a Jackson street.

I could imagine Mississippi because I remembered the “Jew-baiting” of Mississippi senator Theodore Bilbo.

I could imagine Mississippi because I watched Mississippi senator James Eastland lead the charge against a bill that would stop lynching, and Mississippi senator John Stennis bottle up the bill that would guarantee Negroes the right to vote.

All those Mississippi imaginings. All those nightmarish images. How real could they be? It was twenty years since I had fought in the war that was supposed to have buried forever the insanity of “master race.” Yet “Segregation Forever! Integration Never!” was being threatened on the very floor of the U.S. Congress. Fire hoses were being leveled at peaceful demonstrators who wanted only to register to vote, and police dogs were attacking black students who wanted to enter public libraries and to be served in public restaurants. If fascism had been buried in Hitler’s bunker, you would never know it by watching the television news from America’s South in 1964.

Those horrific images were inescapable and haunting, and they finally persuaded me to take my skills as a reportorial artist to Mississippi. I was determined to bring back real images of real people and real places so everyone could see American apartheid for what it really was. In the summer of 1964 I became part of the civil rights movement. One thousand students from the North were volunteering to go to Mississippi to teach in Freedom Schools and to help register Negro voters, and I joined them at their orientation week in Oxford, Ohio. It was the first time since I was a part of the D-day landings in Normandy that I felt myself physically and emotionally involved with a life-and-death Invasion. What I learned during that remarkable week from the black civil rights workers from the Delta was how different this Invasion would be. Unarmed, with no possible protection from the local police, the local press, the local clergy, the local congressman, or the local leaders of the business community, we would have to face down the guns and hostility of a totally closed society.

Tracy Sugarman is a nationally recognized illustrator whose art has appeared in magazines and books, and has been featured on PBS, ABC-TV, NBC-TV, and CBS-TV. His collection of art from World War II has been acquired by the Veterans History Project, a program of the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. He is the author of Stranger at the Gates: A Summer in Mississippi; My War: A Love Story in Letters and Drawings; and Drawing Conclusions: An Artist Discovers His America.

The American Folklife Center was created by Congress in 1976 and placed at the Library of Congress to "preserve and present American Folklife" through programs of research, documentation, archival preservation, reference service, live performance, exhibition, public programs, and training. The Center includes the American Folklife Center Archive of folk culture, which was established in 1928 and is now one of the largest collections of ethnographic material from the United States and around the world. Please visit our web site.

| ||||