| |

|||

|

|

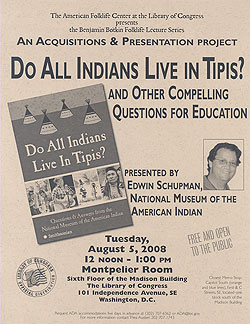

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress August 5, 2008 Event Flyer Do All Indians Live in Tipis?

|

|

The American public feels most comfortable with the mythical Indians of stereotype-land who were always there.

-- Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux)

From tom-toms to tipis, dream catchers to kachinas, and Sacajawea to Sitting Bull, America has long been confused about its indigenous peoples. The problem began in the 15th century when Cristóbal Colón stepped off the ship in Hispaniola and, thinking that he was on some islands off the Asian continent, declared that he had found Los Indios. Never known previously as a collective group of people, this was the moment in history when the long march to invisibility and dehumanization began for the Taino, Coweta, Tsalagi, Dinÿ, Ho-Chunk, and thousands of other culturally, politically, and geographically distinct peoples. Of course, it was also the beginning of other very serious consequences of contact and colonialism, including disease, genocide, lands dispossession, cultural suppression, and attempts at forced assimilation.

Over the next several centuries a dizzying array of notions about Indians erupted in the American consciousness. These were fueled at various times by racist, political, and economic agendas, literary and artistic license, romanticized images, and ignorance. The problem with these perceptions is that few of them, if any, were based on information that emanated from within the Native communities themselves. The writer and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe member, Rita Pyrillis, expressed her exasperation in a 2004 article:

No wonder people are confused about who Indians really are. When we’re not hawking sticks of butter, or beer or chewing tobacco, we’re scalping settlers. When we’re not passed out drunk, we’re living large off casinos. When we’re not gyrating in Pocahoochie outfits at the Grammy Awards, we’re leaping through the air at football games, represented by a white man in red face. One era’s minstrel show is another’s halftime entertainment. It’s enough to make Tonto speak in multiple syllables. — “Sorry for Not Being a Stereotype,” Chicago Sun-Times, April 24, 2004.

In its own way, the education system has helped perpetuate the misperceptions and stereotypes. At any given time, the system reflects prevailing public attitudes. Thus, teachers have lacked good quality information and materials to work with. Making paper headdresses at Thanksgiving time is one of the few early educational experiences many people have had in learning about American Indians. Though well intended, this activity violates the meaning behind a very important piece of regalia among some Native peoples, and does little to teach students about the real peoples encountered by the English colonists and others upon their arrival in the western hemisphere.

In 2008, the problem persists, but there are signs of change. The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) is one source of hope and reconciliation. The museum collaborates with Native communities and is committed to using the Native voice in the presentation and interpretation of Native histories, cultures, and contemporary lives. This approach represents a significant shift in museology and offers exciting new opportunities for education. The Museum staff encounters daily the effects of 500 years of confusion about Native America. Visitors come from a variety of educational backgrounds and with a wide assortment of interests and expectations. They also come with questions on many topics and at every level of sophistication. All questions are welcomed, because they provide an opportunity to correct mistaken notions of the past, and to present priorities of native communities. Many of the most common questions from visitors formed the foundation of the book Do All Indians Live in Tipis?

NMAI is not the only organization working to counter historical confusion. Across the country, tribal education departments, tribal museums, and other cultural organizations are telling their own stories through exhibitions, publications, and media. Many universities, non-Native cultural organizations, and government agencies are also working with Native communities and advisors. The education system is changing as well. Federal and state education agencies collaborate more fully with tribes and Native educators. Teachers are eager for good materials, training, and primary resources to help them educate more comprehensively and appropriately. There is hope for the reclamation of truth about American Indians in our society, but much remains to be done, starting with the basics. Native America has always had much more to offer the world than tipis and mascots.

Ed Schupman, July 2008

Washington, DC

The American Folklife Center was created by Congress in 1976 and placed at the Library of Congress to "preserve and present American Folklife" through programs of research, documentation, archival preservation, reference service, live performance, exhibition, public programs, and training. The Center includes the American Folklife Center Archive of folk culture, which was established in 1928 and is now one of the largest collections of ethnographic material from the United States and around the world. Please visit our web site.

| ||||