The Books of the People of the Book

|

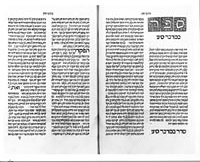

Sefardi Torah Scroll (North

Africa?, eighteenth century?). Torah scrolls are written

without vowels or punctuation and include only the biblical

text. These four columns begin with Exodus 23:6 and go through

Exodus 26:25. |

The twin pillars of Judaism are the Hebrew Bible and the Talmud.

The Hebrew Scriptures -- the book of the "People of the Book"

-- are divided into three main sections: the Torah (Pentateuch);

the Nevi'im (Prophets), and the Ketuvim (Hagiographa).

The Talmud is a massive collection of discussions and rulings

based on the Mishnah, a compilation of laws and customs assembled

in about 200 C.E. Two versions of the Talmud exist: The Jerusalem

Talmud, dating from circa 400 C.E., is based on the discussions

of the sages of Palestine, and the Babylonian Talmud, from circa

500 C.E., recapitulates the debates of the rabbis in the Babylonian

academies.

The prevailing form of the book in antiquity was the scroll.

Ancient texts were copied onto animal skins that had been prepared

to be written on. The individual skins, called parchment, were

then sewn together and the ends were attached to cylindrical handles

or rollers. To this day, Judaism reserves the scroll for the sacred

texts read in the synagogue liturgy. The most sacred Jewish text

is the Torah scroll. Containing the Five Books of Moses (the Pentateuch),

a Torah scroll is handwritten by a specially trained scribe who

pens the text -- letter by letter and word by word -- on specially

prepared parchment. Torah scrolls do not have punctuation, vowel

signs, signatures, colophons, or dates, so the place, date, and

scribe are almost never known -- though we can often surmise the

date and location from paleographic clues. Portions of the Torah

are read aloud in the synagogue on the Sabbath, on holidays, and

during weekday services on Monday and Thursday mornings.

|

Mordechai Beck and David Moss, Maftir

Yonah (The Book of Jonah)

(Jerusalem, 1992). An edition of the Book of Jonah meant

to be recited at the afternoon service on the Day of Atonement,

this volume includes original etchings by Mordechai Beck

and calligraphy by David Moss. It was produced by Sidon

Rosenberg at the Jerusalem Print Workshop. Copyright ©

2000 Bet Alpha Editions, Berkeley, California. (Reproduced

with permission of Bet Alpha Editions)

|

Metavel, illustrator and calligrapher, Yonah

(Jerusalem, 1986). This work is part of the Israel

Museum's series of matchbox books. Illustrated and written

by the Israeli artist and miniaturist Metavel, it includes

vignettes from the story of Jonah and the whale.

|

The Hebraic collections include a Torah scroll (in Hebrew, Sefer

Torah) copied in North Africa, probably in the eighteenth

century, and written in a Sefardi hand. The Sefardim, or Spanish

Jews, are descended from Jews who were expelled from Spain and

Portugal at the end of the fifteenth century. The golden-hued

parchment of this Sefer Torah is prepared in a manner

similar to an ancient method described in the Talmud, using a

chemical process similar to tanning. The Scroll of Esther (in

Hebrew, Megillat Esther), which includes the handwritten

text of the biblical Book of Esther, is read aloud in the synagogue

on the eve and the morning of the Purim festival.

A Scroll of Esther of unusual size and age is held in the Hebraic

Section. Copied in central or southern Europe in the fourteenth

or fifteenth century, this monumental scroll measures some thirty-two

inches high, with each letter about three quarters of an inch

in height. The parchment was prepared using a process typical

of Ashkenazi manuscripts, which resulted in a whiter writing surface

than the one used to prepare a typical Sefardi scroll. Ashkenaz

refers to Germany, and Ashkenazi Jews are these Jews -- or their

descendants -- living in Christian lands. Printing with movable

type, introduced in Europe by Johann Gutenberg in the mid-fifteenth

century, was quickly taken up by Jews in Italy, Spain, Portugal,

and Turkey, who sought to produce and disseminate the literature

of Judaism. In all, some 140 Hebrew works were printed before

1501. Of these Hebraic incunabula, the Library holds 31 titles

in 39 copies.

|

Ariel Wardi, Yemei Beresheet

(Jerusalem, 1992). This work was privately printed

on a hand press by Ariel Wardi, who cut letters and cast

the type especially for this edition, which he bound himself.

Displayed are the words from the opening chapter of Genesis

describing the first six days of creation (Genesis 1:1-31;

2:1-3). (Courtesy Ariel Wardi)

|

Ashkenazi Megillah (fourteenth-

fifteenth centuries?). This scroll is one of the oldest

extant. The shape of the letters as well as the condition

of the parchment help to establish where it was created

and the date of its completion.

|

The first dated Hebrew book -- Rashi's commentary on the Pentateuch

-- appeared in Reggio di Calabria, Italy, in 1475. But scholars

point to Rome as the city where Hebrew printing began. Between

1469 and 1472, nine works were printed there -- none bearing a

date or place of publication -- but all bearing the unmistakable

typographic influence of Sweynheym and Pannartz, two German printers

who set up shop in Subiaco, near Rome, and printed Latin books.

It is believed that Rome's Jewish printers learned their craft

from Sweynheym and Pannartz. From these first fruits of Hebrew

printing, the Library of Congress owns a copy of the responsa

of Solomon ben Abraham Adret (the "Rashba") of Barcelona, a thirteenth-century

rabbinic authority, called Teshuvot She'elot ha-Rashba (Rome,

1469-72). The primitive typography of this Rome incunabulum --

the left margin is ragged and only a square font is used -- has

led some to speculate that this work might very well be the first

Hebrew book printed.

|

Psalms, with commentary by David

Kimhi (Bologna?, August 29, 1477). Kimhi's commentary

was often a target for censors. In the passage displayed

here, an owner has handwritten in the margin all that was

inked out by the censor.

|

The first book of the Hebrew Bible to be printed was the commentary

of David Kimhi on the Psalms, which was published in 1477, probably

in Bologna. The volume is one of the most beautiful of early Hebrew

printed works, and its fonts do not appear to have been used for

any other title. The verses are printed in square type and pointed

by hand. The commentary of David Kimhi is in a cursive type. The

Library's copy was heavily censored by Church authorities in Italy,

with whole passages crossed out by the censor's pen. In 1489,

Eliezer Toledano published the first book printed in any language

in Lisbon, the capital of Portugal. Moses ben Nahman's Perush

ha-Torah is a commentary on the Pentateuch. That same year,

Toledano published Lisbon's second printed work, the Sefer

Abudarham, a commentary on the prayers written in 1340 by

David ben Yosef Abudarham. The Library's copies of these and similar

works help document the rich and varied legacy of Iberian Jews

before the expulsions in 1492 from Spain and in 1497 from Portugal.

In the sixteenth century, Hebrew printing spread throughout

Europe and the Near East, with centers established in Venice,

Constantinople, Salonika, and a variety of towns and cities in

Central Europe.

|

Solomon ben Abraham Adret, Teshuvot

She'elot ha-Rashba (Rome, 1469-72). This volume

is opened to responsum 265, in which the Rashba responds

to the question: "Which is to be preferred: A professional

cantor or a volunteer?"

|

Moses ben Nahman, Perush

ha- Torah (Commentary

on the Pentateuch) (Lisbon, 1489). Nahmanides's commentary

on the Pentateuch is the first book printed in any language

in Lisbon. Illustrated here is the opening page of the Book

of Numbers, Ba- Midbar, the fourth of the Five

Books of Moses.

|

One of the most important and well-known of early Hebrew printers

was the "wandering printer," Gershom Soncino. He set up shop in

the town of Soncino in Lombardy, and from there he made his way

through Italy, issuing books in Casalmaggiore, Brescia, Barco,

Fano, Pesaro, Rimini, Cesena, and Ortona. From Italy, he journeyed

to Turkey, where he printed Hebrew books in Salonika and Constantinople.

Over the course of his career, which began in 1488 and ended in

1534, some two hundred works issued from his press -- roughly

half in Hebrew and half in Latin and Italian.

|

David ben Yosef Abudarham, Abudarham

(Fez, 1516). The first book printed in Africa, this

edition of the Abudarham is a reprint of the Lisbon 1489

edition. The Abudarham outlines religious customs and practices

according to the Sefardic rite.

|

Sefer Kol Bo (The

complete book) (Rimini, 1526). The title page displays

Gershom Soncino's printer's mark, a tower flanked by the

biblical verse, "The name of the Lord is a strong tower:

the righteous [one] runs into it and is set up on high"

(Proverbs 18:10).

|

The first book printed on the continent of Africa was a Hebrew

book, the second edition of the Sefer Abudarham, published

by Samuel Nedivot and his son Isaac in 1516 in Fez. Samuel Nedivot

learned the craft of printing in Portugal, probably in the shop

of Eliezer Toledano, and after the expulsion from Portugal, he

found haven in Morocco. His first publication there was an almost

exact copy of Toledano's 1489 Lisbon edition. Clearly, the printer

of the Fez edition had before him the Lisbon 1489 edition and

sought to reproduce it line for line and letter for letter. The

book represents an object lesson in how, after a catastrophe such

as the expulsion from Portugal, a spiritual and cultural legacy

is rebuilt and transmitted from one generation to the next.

In 1515, Daniel Bomberg, a Christian from Antwerp, received an

exclusive privilege from the Venetian Senate to print Hebrew books

in Venice. Bomberg's press became the most important Hebrew press

in sixteenth-century Europe, issuing some 230 titles before its

demise in 1549. Bomberg published the first edition of the Rabbinic

Bible (1516-17) -- the Hebrew Scriptures accompanied by a selection

of traditional rabbinic commentaries -- and the first complete

edition of the Talmud (1519-23). The layout and pagination of

the Bomberg Talmud became the standard for virtually all subsequent

editions of the Babylonian Talmud that have appeared to this day.

|

Mikra'ot Gedolot (Rabbinic

Bible) (Venice, 1516-17). This Hebrew Bible is opened

to the end of the Book of Samuel and the first verses of

the Book of Kings.

|

Talmud, Sanhedrin (Venice,

1520). The form of the page of the Talmud has remained constant

through the centuries: the text in the center in square

script, surrounded by the commentaries in a smaller cursive

script.

|

The first edition of the Zohar (The Book of Splendor) -- a classic

of Jewish mysticism -- appeared in Mantua in 1558. The second

volume of the Library's three-volume set is printed on blue paper,

marking it as a deluxe limited edition prepared especially for

a wealthy patron.

In the seventeenth century, Amsterdam became a center of Hebrew

printing. One of its leading printers, Joseph Athias, published

a noteworthy edition of the Hebrew Bible in 1667, which earned

him a gold medal from the Dutch government. The edition, which

was intended for both Jews and Christians, was edited by University

of Leyden scholar Johannes Leusdan.

|

Sefer ha-Zohar (Book

of splendor) (Mantua, 1558). This edition of the Zohar

-- the central text of Jewish mysticism -- is printed on

blue paper, thereby marking it as a deluxe edition.

|

Biblia Hebraica (Amsterdam,

1667). This edition of the Hebrew Scriptures won an award

for its publisher, Joseph Athias. Note the four-letter name

of God, the Tetragrammaton, surrounded by light, at the

head of the title page.

|

|