Back to Collection Connections

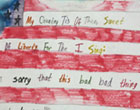

[Detail] My Country Tis of Thee. Brittany Woodward, 2001.

Collection Overview

Based on a similar project created after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the September 11, 2001, Documentary Project documents eyewitness accounts, expressions of grief and other commentary on the events of September 11, 2001. Included in this presentation are photographs, drawings, audio and video interviews and written narratives. Of special interest are interviews with people who were in Naples, Italy at the time of the attacks

Special Features

These online exhibits provide context and additional information about this collection.

Historical Eras

These historical era(s) are best represented in the collection, although they may not be all-encompassing.

- Contemporary United States, 1968-present

Related Collections and Exhibits

These collections and exhibits contain thematically-related primary and secondary sources. Browse the Collection Finder for more related material on the American Memory Web site.

- After the Day of Infamy: "Man-on-the-Street" Interviews Following the Attack on Pearl Harbor

- Witness and Response: September 11 Acquisitions at the Library of Congress

Other Resources

Recommended additional sources of information.

Search Tips

Specific guidance for searching this collection.

To find items in this collection, search by Keyword or browse by Title, Subjects, Audio, Photograph or Drawing, Video or Written Narrative.

For help with general search strategies, see Finding Items in American Memory.

U.S. History

The day after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and the crash of the fourth hijacked airliner in Pennsylvania, the American Folklife Center called upon the nation’s folklorists and ethnographers to document America’s reaction. A sampling of the material collected through this effort was used to create the September 11, 2001, Documentary Project.

The collection captures the voices of men and women from diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, a cross -section of America. Included are interviews with people who were in the World Trade Center and the Pentagon during the attacks. The majority of the interviews, however, are from other parts of the country, from those who first heard the news on television or radio. In all, materials were received from 27 states and a U.S. military base in Naples, Italy. In addition to audio and video interviews, the online collection features written narratives, photographs, and drawings by elementary students.

Teachers using the collection should be aware that some of the stories told in the interviews are disturbing reminders of the magnitude of the tragedy. Teachers should help students prepare to deal with the emotions that the interviews may evoke.

The American Folklife Center’s September 11, 2001, Documentary Project is modeled on a similar initiative, conducted 60 years earlier, documenting national sentiment following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. After the Day of Infamy: "Man-on-the-Street" Interviews Following the Attack on Pearl Harbor can be used to show similar reactions to those recorded in the September 11, 2001, Documentary Project.

Eyewitness Accounts of the Attacks

On September 11, 2001, American Airlines Flight 11 from Boston’s Logan International Airport struck the north tower of the World Trade Center at 8:46 a.m. United Airlines Flight 175, also from Boston, crashed into the south tower at 9:03 a.m. Less than 35 minutes later, American Airlines Flight 77 from Washington Dulles crashed into the Pentagon. A fourth hijacked plane, United Flight 93 from Newark, crashed southeast of Pittsburgh at 10:02 after passengers, hearing of the previous terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, fought with hijackers; the plane crashed in a field about 20 minutes flying time from Washington, D.C., where the hijackers had planned to fly into another symbol of the United States, either the Capitol or White House.

The attack on the World Trade Center is vividly etched in the minds of eyewitnesses. Lakshman Achutan, an economist, was attending a meeting on the ground floor of the north tower when it was attacked. He described the initial impact, his escape, and his view of the second plane as it approached the south tower in an interview conducted on October 31. On her way to work in Greenwich Village, Kristin Vogel saw the first tower collapse, one of the events she tearfully recounted in her interview.

Carol Paukner, a New York Transit Police Officer, was stationed one block away from the World Trade Center in the subway system when she received a call about “unknown conditions.” She described in an interview the scene as she emerged from the subway, her efforts to assist victims, and the aftermath of the second plane’s impact with the south tower. College student Denise Weiss was evacuated from her school near the World Trade Center and saw the north tower in flames and an airliner slam into the south tower.

Terry Benczik witnessed the burning towers of the World Trade Center from a train nearing Newark Penn Station.

The train was nearing Newark Penn Station, where I would then switch to a PATH train that would take me inside the World Trade Center. All of a sudden, I heard a sound that I had never heard human voices make before. The noises were a mix of surprise, revulsion and something else I still cannot name. Did the train car strike an animal? A person? People on the train were looking out the window and making the strangest noises. There weren't words spoken, just a rush of air being taken in and finally lots of "noooooooooo!"

I realize now that they had seen an airplane hit Tower Two of the World Trade Center. We went to the window and saw both towers on fire.

“I work there.” I explained. I had tears in my eyes. My stomach was tight. “My friends are inside there. I've worked there about 12 years. My friends are there.”

We had no idea what was happening. I was remembering how awful the bombing in 1993 was. Back then I was in the mail concourse, a few feet away from the glass entrance into Building One. About 70 feet away from me the bomb had blown out the wall and filled the air with thick dust as it shook the ground. Six people died that day. Looking at the towers, seeing the flames from across the Hudson River, I knew this was much worse than 1993 had ever been. The site [sic] of all the smoke and flame filling the air made me shudder for those inside. I had no idea if everyone I worked with was gone or not. I kept hoping that like me, everyone was inexplicably late for work. . . .

In the train station Mathangi and I sat near the platform. People drifted up to us in a state of semi-shock. Most of them said, “I work in the Trade Center but today I was late.” We asked several of them to sit on the bench with us. I felt it was important to tell one woman that she was safe and had to sit with us. She just looked so lost. Mathangi lent me her cell phone. I called my mother and I had never heard such hysteria in Mom’s voice. “I’m okay, Mom. I’m okay. Tell Sis. Let her know. I’ll be home soon as I can. I love you.” Mathangi passed her cell phone around to perfect strangers on the platform. People were saying the same things to the people they loved.

Excerpted from “Narrative by Terry Benczik”

Listen to portions of two or more of the audio interviews cited above, focusing on the parts that provide eyewitness accounts of the attacks and of events in New York City in the days that followed the attacks.

- What events does each of the eyewitnesses recount? How are their accounts different? How are they similar?

- What role did technology play in how the eyewitnesses experienced the events of September 11? In what ways, if any, did technology help people? In what ways, if any, did technology fail to help people?

- What emotional responses do the eyewitnesses describe? Which emotions seemed to be the most commonly experienced immediately after the attacks? Which were most common days or weeks after the events?

- How do the eyewitness accounts add to your understanding of what you previously knew about the events of September 11, whether from seeing the events on television, reading about them, or learning about them in school? Describe what you believe to be the unique value of eyewitness accounts of major historical events.

- What do these accounts reveal about the values of the individuals describing the events of the morning of September 11? How might these values affect the way in which they recall the events? What other factors might affect their recollection of the events?

American Airlines Flight 77 from Washington-Dulles International Airport crashed into the Pentagon at 9:37 a.m. William Lagasse, Chadwick Brooks, and Donald Brennan were Pentagon police officers on duty at the time of the attack. Lagasse was in the process of refueling his police car when the American Airliner flew past him so low that its wind blast knocked him into his vehicle. In an interview conducted in December 2001 , Lagasse described the secondary explosions and the search and recovery of injured Pentagon personnel. Brooks saw the hijacked plane clip lampposts and nosedive into the Pentagon and described the ensuing scenes of chaos in his interview, taped November 25, 2001.

The third officer, Donald Brennan, described standing in jet fuel amidst

the wreckage and bodies of the deceased. In his interview

on November 18, 2001, he told of how he attempted to rescue people in

a section of the Pentagon before it collapsed.

Search the collection using the search term Pentagon police for additional

eyewitness accounts of the crash and rescue efforts.

- What was the scene at the Pentagon as described by the eyewitnesses?

- What similarities do you find between these eyewitness accounts and descriptions of the situation in New York? How similar are the descriptions of psychological effects of the attacks? Do you think police officers faced more serious psychological effects than civilians? Why or why not?

- What did the police officers have to say about heroism and unity in the wake of the attack on the Pentagon? Were you surprised by any of their comments? If so, why?

- What relationship did the interviewer have to the police officers? Do you think this relationship might be significant in terms of analyzing the stories shared with her? Why or why not?

The Attacks as Experienced via the Media

Of course, most Americans were not eyewitnesses to the attacks; most learned about the tragedy from television or radio broadcasts. Below are listed interviews with people who watched the events of September 11 from various locations around the country.

- Billie Jo McAfee, South Lake Tahoe, California

- Peter V.Z. Roudebush, Fort Dodge, Iowa

- Melanie Jean Whipple, East Lansing, Michigan

- Patti Chapman, San Diego, California

- Cindy Mediavilla, Los Angeles, California

- David Harmon, Portland, Maine

Listen to several of the interviews above; you may want to work with a group, splitting the interviews listed among group members and sharing the information gained. Use these interviews or others from people who watched events unfold on television to answer the following questions:

- Compare the psychological and emotional responses of these individuals with those of eyewitnesses. What similarities do you note? What differences?

- Do people’s emotions and fears seem to vary according to where they lived—in the country’s interior or near a coast, in a small town or a big city?

- What are these interviewees’ perspectives on the media’s coverage of the events?

- How do you, as a listener and student of history, respond to the eyewitness accounts versus those of people who watched the events on television? How might your response to the accounts influence the way you construct a historic account of September 11?

Public Response to the Attacks

Lillie Haws, a bar owner in Brooklyn, was not an eyewitness to the attacks but did see firsthand events that occurred afterward. She described a scene in her Brooklyn bar around midnight on September 11, as friends and acquaintances entered the closed bar from the back door.

We had about 50 people in the bar. And then the firemen came in from our local ladder companies. . . . And the smell that was on their bodies, the soot, the burning smell, and their ears were blackened and they had burns. They came in and they asked me how I was, which I thought was just phenomenal, being that they had just been in the midst of a catastrophe that we’ve never known in our history in this country, especially in New York. …My friends started circling around them, and everybody just wanted to be with them. And that was the closest that really anybody that was here had gotten to this disaster. And so we decided, let’s just give it a go, let’s just all be together, stay close together. They cried, they laughed–mostly laughed which I couldn’t believe because they really just tried to find some kind of comfort in laughter. And we rang in the night, probably all night, and took care of them. I’ll never forget that day, and those guys’ faces. And I looked, I looked at guys coming in, and I kept looking for certain guys, and I didn’t see their faces. And of course I assumed the worst. And I asked the other firemen, “Where’s Christian, where’s Sal, where’s these guys?” And they were among the missing. And that was my day of September 11, 2001.

Excerpted from “Interview with Lillie Haws, New York, New York, November 12, 2001”

Listen to more of Lillie Haws’s interview and answer the following questions.

- How does Haws describe the firemen who came to the bar?

- In what ways did Haws and others in her community reach out to assist firefighters?

- What can be inferred from Lillie Haws’ interview about the way in which people came together during the tragedy?

Far from the actual attack sites, Mayor Douglas Thompson of Logan, Utah, described how his community came together in the weeks that followed:

Then my thoughts were “What can we do to pull our own community together and particularly help the feelings of grief and mourning that we all felt, even if we didn’t have someone directly involved in the tragedy?” . . . We got together with other community leaders, mainly church leaders, to put together a memorial that was absolutely amazing because it was the first time in decades that . . . leaders of all the churches in the community actually got together and talked about something. . . . and that group has continued on to meet to try to deal with community-wide issues . . .

. . . we’ve pulled together as a community. . .. We’ve been doing things as a community that we’ve not done before in the past. People gave blood for the first time in their lives and hopefully they’ll continue to do that. Feelings of patriotism are higher now that any time I’ve seen in my lifetime and I hope that will continue. . . . I hope we can keep that feeling of love and concern for each other and the feeling of patriotism and loyalty.

Excerpted from “Interview with Douglas Thompson, Logan, Utah, November 14, 2001”

As Mayor Thompson highlighted, taking action after a catastrophic event, whether through remembering those who died or helping those who survived, helps people deal with their grief. Similarly, demonstrating unity as a community also helps combat the sense of powerlessness that such events produce—in unity, people find strength. Look for evidence in the collection of the ways in which people remembered and helped victims of the terrorist attacks and showed unity as a nation. Examine the Photographs and Drawings in the collection, and use such Subject listings as disaster relief and patriotism to locate information about the national response. Create a chart or a collage that shows ways in which people provided relief assistance and demonstrated a sense of national unity following the September 11 attacks.

Not every response was positive, however. Soon after the attacks, the media reported assaults on people believed to be Arabs/Muslims. Some people interviewed for the September 11 Documentary Project described new feelings toward Arab-Americans and Muslims:

I hate to admit this but sometimes I feel suspicion and mistrust when I see people of Middle Eastern descent. I look at them differently. I don’t treat them differently, but I feel some fear in my heart and that’s really, really hard for me to admit because it doesn’t feel good.

Excerpted from “Interview with Lorraine Scott, Anaheim, California, October 22, 2001”

Use the interviews listed below to begin exploring the issues of post-9/11 prejudice and discrimination. What evidence can you find to assess the seriousness of the issues? What strategies do interviewees suggest for dealing with the issues? How effective do you think these strategies were?

- William H. Moulder, Chief of Police in Des Moines, Iowa, described city leaders’ efforts to ensure that retaliation would not occur in their community.

- Arshad Yousufi, a leader in the Muslim community in Colorado Springs, Colorado, discussed people’s responses toward him in the wake of the attacks and his efforts to educate the community about Islam.

- Ran Kong, a student from Greensboro, North Carolina, described being mistaken for an Arab and the fears she experienced about her personal safety.

- Adeel Mirza, an attorney in Madison, Wisconsin, talked about incidents in which family members have been taunted and the dangers of becoming overly nationalistic.

Responding to the Terrorists

While the nation seemed to be experiencing a strong feeling of unity, interviewees differed in their views on how the nation should respond to the attacks. Many interviewees said that they did not have the expertise to recommend a specific course of action, but expressed support for President Bush. Other individuals had very specific ideas, including Cary Hewitt of Long Beach California, who urged obliterating Afghanistan. Others such as Keith Brown of Orlando, Florida, called for restraint and dialogue. Matthew Singletary of Alma, Michigan, voiced opposition to a grand war on terrorism and recommended instead swift covert action to kill Osama Bin Laden and his confederates; he also expressed the need for people to be informed and discuss issues related to the attacks.

Beliefs about how the United States should respond to the attacks reflected not only different philosophies but also different views on the reasons behind the attacks. In a written narrative, Niloofar Mina, an Iranian exile, likened the victims of the World Trade Center to the victims of violence in the Middle East.

… I felt for the WTC victims the same way I feel for the continuing plight of the Palestinian people, the people of Iraq, and for the over 2 million Iranian and Iraqi people who were killed in a war that was used by the U.S. to destabilize and devastate the Gulf region and fund terrorist groups in Central America. A war that took the lives of many of my friends. This is precisely the reason why the current talks of revenge and war, and the patriotic sentiments forced on the American people scare me. Clearly, violence diminishes us.

Excerpted from “Narrative from Niloofar Mina”

Rev. John Mack, pastor of the First Congregational United Church of Christ in Washington, D.C., reflected a different perspective in a narrative written on September 30, 2001.

The people who tell me that I am responsible, or that the country is because of its foreign policy, or that we're just getting a taste of what everyone lives with are frankly driving me a little crazy. …Because we give $20 billion dollars to Israel each year, does that mean we should have expected this, or that we are responsible? I don't really believe that the people who planned this evil knew what they were doing. Even as they indoctrinated the young men who did it, I don't believe they grasped the enormity of the evil that had hold of them. They kept themselves at too great a distance to appreciate the evil killing of the innocents, of their own brothers and sisters and children.

Excerpted from “Sermon by Pastor John Mack”

Keith Baker, a high school social studies teacher, concluded that one of the root causes of September 11 was an attack on our culture and freedom, stating that the terrorists “consider our culture anathema to what they believe in.” Others, however, took issue with that belief. Adeel Mirza, an attorney from Madison, Wisconsin, claimed that the terrorists acted in response to American foreign policy.

Interviewees also expressed differing opinions on the legitimacy of abridging civil liberties as a result of the terrorist attack and the resulting War on Terror. For example, Lorraine Scott of Anaheim, California, expressed the belief that the government should do whatever is necessary even if it infringes on civil rights. On the other hand, David Wasson, a high school student in Belleville, Illinois, remarked that if Americans give up their civil rights because of the attack, then the terrorists win.

- Make a chart with three columns as shown below

- In the first column, list three areas of disagreement among Americans following September 11. In the September 11, 2001, Documentary Project collection, find at least three different views on each area of disagreement identified. For each view, select a quote from an interview that represents that view and place it in the third column. What does this exercise tell you about Americans? Is this insight important? Why or why not?

- Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, some of the people interviewed for the “man-on-the-street” interviews collected by the American Folklife Center were asked to address their remarks to President Roosevelt. Pick two interviewees who disagreed in one of the areas you identified above. Reframe their remarks as if they were directed to President Bush.

- In his interview, high school teacher Carl Day of Alton, Illinois, said “Freedom of speech has to be protected, especially in a national crisis . . . Hostility against a difference of opinion is not a good thing. We need differences of opinion if only to determine how right we are or in some cases exactly how wrong we are. So I think freedom of speech is to be protected at all levels and at all costs, especially in times of emergency where people are prone to give up certain freedoms in exchange for security and safety.” Do you agree with Day’s opinion? Use what you have learned about Americans’ views on responding to the attacks of September 11 to support your position.

Critical Thinking

Chronological Thinking: Distinguishing Between Past, Present, and Future Time

The interviews in the September 11, 2001, Documentary Project are not just oral histories. Most interviewees not only describe their experiences on September 11 and in the days afterwards but also provide opinions on the events and possible responses to them and make predictions about how life will change in the United States in the future.

In a group interview, a Harvard instructor and three students share their recollections of September 11. Listen to this interview and take note of (1) recollections of actual events/experiences that occurred on September 11 and later, (2) the participants’ opinions about various events, and (3) their predictions about future consequences of the terrorist attacks. Why is it important to distinguish between fact and opinion? Between past events and predicted future events?

Historical Comprehension: Reading Narratives Imaginatively

People’s past experiences, their family backgrounds, their profession, and other personal factors influence how they experience historic events. Thus, understanding who a person is can be useful in reading that person’s account of a historic event.

Read the personal narrative by Kathleen Clark, who was visiting in New York at the time of the attack on the World Trade Center. First read the narrative to learn about Clark as a person. What can you discern about where she lives, her profession, her family, her interests and beliefs, and previous experiences? Write a brief profile of Clark that highlights important information you have gleaned about her life and background.

Reread Clark’s narrative. Look for evidence that her background and experiences affected her reaction to the terrorist attacks. Give three examples of ways in which Clark’s experiences and background might have affected her response to the events of September 11.

Find at least one additional narrative or interview in which there is evidence of how an individual’s response to the events of September 11 was shaped by his or/ her background and experience. Three possibilities are the narrative by Niloofar Mina and the interviews with Jessie Willie Smart, Sr. and Amy Amadasu but many other accounts also provide such evidence. Based on the evidence you have gathered, make a general statement about how an individual’s background and experiences influence their response to historic events.

Historical Analysis and Interpretation: Strengths and Weaknesses of Oral History

Oral histories are firsthand accounts. They provide insight into how ordinary people experienced extraordinary events. However, they are subjective, based on individual memory, which studies on eyewitness testimony have shown to be flawed. Strong emotions and the passage of time are among the factors that can influence memory.

Michael Quintero provided a highly descriptive (and occasionally profane) account of his experiences on September 11; he acknowledged that, in December when he is recording his thoughts, he cannot remember every detail of the day’s events. Listen to Quintero’s interview and answer the following questions:

- What parts of September 11 does Quintero seem to remember particularly well? What information suggests that he remembers those events well? Could there be another explanation for why these events are so vividly portrayed? What benefit does having access to these vivid accounts provide?

- What details of the day does Quintero acknowledge not remembering? Why do you think these events are less vivid in his memory?

- Listen to Quintero as he tries to remember where he spent the night on September 11. Does hearing him talk through this lapse in his memory cause you to think differently about the recollections of eyewitnesses? Why or why not?

Historical Analysis and Interpretation: Considering Multiple Perspectives and Formulating Questions for Inquiry

Melanie Jean Whipple, a 19-year-old student from East Lansing, Michigan, expressed anger about people profiting from the tragedy in her interview:

Furthermore, whoever started making all of these Tt-shirts, I’d like to just beat the crap out of them. It’s like they cashed in on America’s tragedy. I mean, this did not happen for 24 hours before I saw “Proud to Be American” shirts and, you know, shirts with pictures of Bin Laden on it with a target sign on his head, and bumper stickers and, you know, everything else. . . . The industry just cashed in on this tragedy. I mean, I guess that’s part of America, but still, like, is that right? Everybody wants to show their devotion to America, so they buy an American flag t-shirt. Well, that’s making money off of them. I’m pretty sure that, although 10 percent of the proceeds may have gone to, you know, New York City, I doubt that all of them did. I’m sure somebody made a bundle on all this. And I think it’s ridiculous and absolutely, incredibly rude and it really, really angers me that something like this would happen when our country faces this great tragedy and people are like, “Ooh, how can I put this on a shirt and make ten bucks a pop off of it.”

Excerpted from “Interview with Melanie Jean Whipple, East Lansing, Michigan, November 25, 2001”

- What values are expressed in this excerpt from Whipple’s interview? Do you or disagree with her point?

- Imagine that you are the boy in the picture (or his parents). How would you justify buying the T-shirt?

- What assumption about profits does Whipple make? Formulate a research question that would allow you to test the accuracy of her assumption. How could you go about finding an answer to this question?

Historical Issues-Analysis and Decision-Making: Examining Decisions of Ordinary Americans

While U.S. leaders clearly faced many decisions in the months and years following the terrorist attacks, ordinary people had to make many decisions as well. People had to make decisions in their personal lives—how to respond to the attacks, whether to fly again, what safety precautions to take, for instance—but many also faced important decisions in their work lives. The people listed below described work-related decisions they made or decisions made by others that affected them directly.

- Cindy Mediavilla, Los Angeles, California (go to 9:17 into interview)

- Beth Whedon, Colorado Springs, Colorado

- Caroline Lederer, New York, New York (beginning of part 2 of the interview)

Listen to these interviews and identify the profession involved and the decision made in each. How was each decision necessitated by September 11? In what other professions might people have been asked to make decisions as a result of the terrorist attacks? Ask two adults whom you know whether their jobs were affected by September 11 and whether they had to make any decisions because of September 11. Share what you learned with your classmates. On the basis of the information you and your classmates have gathered, make a general statement about the kinds of decisions people faced in their work lives following September 11.

Historical Research Capabilities: The 1993 Attack on the World Trade Center

Listen to excerpts of interviews with Daniel Dominguez (14:00 into the interview) and Lateshe Lee (very end of interview), recalling the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center. Research newspapers and periodicals reporting on the earlier bombing of the building.

- Why do Dominguez and Lee claim that New York “fell asleep” after the 1993 bombing?

- Who was held responsible for the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center? What appeared to be the purpose of the bombers?

- How did the public at large respond to the bombing?

- What measures were taken to secure the World Trade Center after the 1993 attack?

- What do you think U.S. authorities learned as a result of the 1993 attack?

When asked to assess the response of New York’s mayor, Rudolph Giuliani, student Denise Weiss replied:

I think our mayor, Mayor Giuliani, is the most amazing person there is. It’s very hard to react, and what to do, in such an instance, to immediately respond. . . . And Giuliani did an amazing job. I don’t think he could have done more. He did as much as he could. He’s an amazing man.

Excerpted from “Interview with Denise Weiss, New York, New York, November 7, 2001”

Search the collection for other people’s reflections on the leadership of Mayor Giuliani and President Bush. What characteristics do people seem to be looking for from leaders in a time of crisis? Conduct additional research to assess the leadership provided by city and national leaders during the immediate aftermath of the crisis. Use what you have learned to write a job description for a “Leader in a Time of Crisis.” ]

Arts & Humanities

Poetry

Definitions of poetry are almost as numerous as poems, but one definition seems to have particular resonance when considering poems written about catastrophic events like the September 11 terrorist attacks. The poet Edwin Arlington Robinson defined poetry as “language that tells us, through a more or less emotional reaction, something that can not be said.”

Keep this definition in mind as you explore poetry in the collection. One poem from the collection is reproduced below. You can locate other poems by searching the collection using poem as the search term. Note that one poem is read aloud by the poet, Dick Stahl; his poem can be found at the five-minute mark in his interview. You may also want to read the song lyrics written by Cletus Kennelly.

Penn Station Yesterday

By Ethel LebenkoffA stranger-- well dressed woman cries out to me 'why doesn't the national guard have guns?'

(Hoping that guns will make us safer)

GUNS make us SAFE?How will they know? Who is and who is not

Could the same woman who spoke to me be herself a brilliant terrorist?

Can the man with the yarmulke be a terrorist?

Are the two coffee skinned boys sitting next to me at the lecture about the New York

Skyline terrorists?Return to normalcy

That is not possibleNormalcy is in the process of transformation

We can just gesture as we did in the pastAnd those of us who frolicked in freedom

will always remember

Unable to explain

Use the following questions to guide your analysis of the poems you have selected:

- Highlight language in the poems that you find beautiful or expressive. What about the language appeals to you?

- What evidence do you find that poetry communicates through “a more or less emotional reaction”? What emotions are evoked? How do the language, rhythm, or structure of the poem evoke emotions?

- Do you think that the poems convey “something that can not be said”? Based on your analysis of the poems, how might you explain this phrase to someone who is unfamiliar with poetry?

- Considering your answers to the above questions, has Edwin Arlington Robinson provided a valuable definition of the word poetry? Explain your answer.

Sending a Message

Americans use their First Amendment freedoms in a variety of ways. One way

is by sending messages through signs, placards, and even items of clothing.

Some such messages are designed to persuade, others to comfort, still others

to entertain or inform.

Examine the messages in the four pictures shown below. Then answer the questions

that follow.

- Who is the intended audience for each of these messages? Some possible audiences are the terrorists, average Americans, people directly affected by the attacks, the U.S. government, and people protesting government actions.

- Restate each message in your own words, keeping the intended audience in mind.

- Which of the messages do you agree with? Why? Which do you disagree with? Why?

- Create a sign or placard that expresses a message you would like to convey. The focus should be on the events of September 11. Choose an audience and craft your message for that audience.

Expressing Emotion through Art

Drawing is often used to release emotions, especially among children who have witnessed a horrific event, such as television coverage of the terrorist attacks of September 11. According to experts in the field, “With guidance and support, it [drawing] can help traumatized children to make sense of their experiences, communicate grief and loss, and become active participants in their own process of healing, beginning the process of seeing themselves as ‘survivors’ rather than as ‘victims’” (“Using Art in Trauma Recovery with Children,” from the American Art Therapy Association).

Fourteen drawings by third grade students from Knoxville, Tennessee, are included in the September 11, 2001, Documentary Project as a “Gallery.” Examine the drawings by Hannah Beach, “Crying Towers”; Meagan Yoakley, “No, No”; and Eddie Hamilton, “It’s OK.” Also examine the panoramic drawing by second-grade students at Van Horne Elementary School in Tucson, Arizona.

- What emotions are the children expressing in these drawings?

- What do the titles of the drawings reveal?

- What message is Eddie Hamilton conveying by showing the Statue of Liberty consoling a Bald Eagle?

- Wat do the drawings indicate about the effects of the terrorist attacks on young children?

Creating a Radio Program Based on the Collection

When the “Man-on-the-Street” and “Dear Mr. President” interviews were collected following the attack on Pearl Harbor, they were used as the basis for two radio programs. Imagine that you are the director of a radio station that is planning a series of retrospective reports on the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Each report will be five minutes long. You think that the interviews in the September 11, 2001, Documentary Project could serve as the basis for one of the reports.

Work with a team of producers to create a script for the program. Your team should scan the interviews and narratives available, looking for themes that you want to highlight. When you have selected a theme, look for interviews that provide insight into that theme. Select excerpts that illustrate the points that you want to make. Decide in what order you will use the excerpts, and write a narrative that will introduce the report, take listeners into and out of the interview excerpts, and end the report.