Prewar Mapping

War, like necessity, has been called the mother of invention. The same might be said of cartography, for with every war there is a great rush to produce maps to aid in understanding the nature of the land over which armies will move and fight, to plan engagements and the deployment of troops, and to record victories for posterity to study and admire. The American Civil War is a classic example of the effect that war has had on cartography.

Reproduced from Civil War Maps: An Annotated List of Maps and Atlases in the Library of Congress compiled by Richard W. Stephenson, 2nd ed. (Washington: Library of Congress, 1989).

On the eve of the Civil War, few detailed maps existed of areas in which fighting was likely to occur. Uniform, large-scale topographic maps, such as those produced today by the U.S. Geological Survey, did not exist and would not become a reality for another generation. In most cases, the best medium-scale, published maps available in 1861 were those sponsored by various state legislatures.

In the Eastern theater (i.e., southern Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia) both Union and Confederate military authorities initially relied on several maps: that of Pennsylvania (scale 5 miles to 1 inch) published in 1860 by Rufus L. Barnes of Philadelphia; Fielding Lucas, Jr.'s map of Maryland (scale 5 ½ miles to 1 inch) published in Baltimore in 1852; and the nine-sheet map of Virginia by Herman Böÿe (scale 5 miles to 1 inch), revised by Ludwig von Buchholtz and published in Richmond in 1859. Each was actually a revision of a map published long before the Civil War: the Pennsylvania map was originally compiled and published by John Melish in 1822; the map of Maryland was first issued by Lucas in 1841; and the map of Virginia was first copyrighted by the state in 1826 and offered for sale in 1827.

The most detailed maps available in the 1850s were of selected counties. Published at about the scale of one inch to a mile, these commercially produced wall maps showed roads, railroads, towns and villages, rivers and streams, mills, forges, taverns, dwellings, and the names of residents.[1] The few maps of selected counties in Virginia, Maryland, and southern Pennsylvania that were available were eagerly sought by military commanders on both sides. In his communication to the American Philosophical Society in March 1864, map publisher Robert Pearsall Smith told how, on the eve of the invasion of Pennsylvania in 1863, Confederate soldiers in advance of the main army confiscated all the maps of Franklin, Cumberland, and Adams counties that they could find:

For a day or two, not a map of the seat of war was to be obtained at Harrisburg for the use of the Governor and his staff. General Couch had but a single copy at his headquarters. An order on Philadelphia could only be filled by sending out a special agent, who succeeded, at great personal risk, in procuring one or two of each county. Judge Watts, of Carlisle, informed me that the maps were torn hastily from the walls of the farmers' houses, and sent with the horses and other valuables for safety, over the North Mountain, into the Juniata Valley. The rebel visitation was very complete; he thought it likely that not a single house had been overlooked...A rebel general is understood to have made a reconnaissance of these counties previous to the invasion under the guise of a map-peddler, and while selling some of a more general character, no doubt bought up county maps to be used in the invasion.[2]

Interest in county maps was substantiated by Confederate cavalry officer Lt. Col. William W. Blackford who wrote:

At Mercersburg I found that a citizen of the place had a county map and of course called at the house for it, as these maps had every road laid down and would be of the greatest service to us. Only the females of the family appeared, who flatly refused to let me have the map, or to acknowledge that they had one; so I was obliged to dismount and push by the infuriated ladies, rather rough specimens, however, into the sitting room where I found the map hanging on the wall. Angry women do not show to advantage, and the language and looks of these were fearful, as I coolly cut the map out of its rollers and put it in my haversack.[3]

Richard W. Stephenson, Civil War Maps

References

- For a list of county maps in the Library of Congress,

see Richard W. Stephenson, Land Ownership Maps (Washington: Library of

Congress, 1967), 86 pp.

Back to Text - Robert Pearsall Smith, "Communication . . . Respecting

the Published County Maps of the United States," American Philosophical Society,

Proceedings 9 (March 1864): 350.

Back to Text - William W. Blackford, War Years with Jeb Stuart

(New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1945), p. 165.

Back to Text

Union Mapping

Federal military authorities were keenly aware that they were unprepared to fight a war on American soil. Any significant campaign into the seceding states could be successfully carried out only after good maps, based on reliable data from the field, had been prepared. Existing Federal mapping units, such as the Army's Corps of Topographical Engineers and Corps of Engineers, the Treasury Department's Coast Survey, and the Navy's Hydrographic Office, therefore, were considered of immense importance to the war effort and were given full support to expand and carry out their missions.1 Although Federal authorities were unprepared to fight a war, they had one great advantage over the Confederacy: they were able to build upon an existing organizational structure, which included equipment and trained personnel.

Mapping of Washington, D.C.

As the war began, perhaps the most vulnerable area of the Union was the nation's capital. Situated on the banks of the Potomac River, Washington, D.C., was located between the Commonwealth of Virginia which ratified the ordinance of secession on April 17, 1861, and Maryland, which initially wavered, but remained a part of the Union. On the evening of May 23, as soon as sufficient troops were on hand in the nation's capital, Federal regiments crossed the Potomac into Virginia and began occupying the strategic approaches to the city. Within the next two months efforts were concentrated on the preparation of earthen fortifications to defend the city from an attack from the South. Throughout the war the defenses of Washington were extended, strengthened, and modified. Entrusted with this important task was Bvt. Maj. Gen. John G. Barnard of the Corps of Engineers. General Barnard served as Chief Engineer of the Army of the Potomac, 1861 to 1862, Chief Engineer of the Department of Washington from 1861 to 1864, and then as Chief Engineer of the armies in the field from 1864 to 1865. In his Report on the Defenses of Washington published after the war, Barnard noted with some pride that:

From a few isolated works covering bridges or commanding a few especially important points, was developed a connected system of fortification by which every prominent point, at intervals of 800 to 1,000 yards, was occupied by an inclosed field-fort every important approach or depression of ground, unseen from the forts, swept by a battery for field-guns, and the whole connected by rifle-trenches which were in fact lines of infantry parapet, furnishing emplacement for two ranks of men and affording covered communication along the line, while roads were opened wherever necessary, so that troops and artillery could be moved rapidly from one point of the immense periphery to another, or under cover, from point to point along the line.2

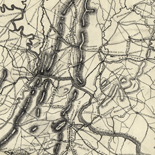

Of the numerous maps depicting the defenses of Washington, D.C., the detailed map compiled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers showing the entire interlinking network of fortifications is of particular importance. Measuring 132 by 144 cm., this remarkable map was made to accompany General Barnard's official report on the defenses of the nation's capital. Albert Boschke's notable 1861 printed map of Washington, D.C., was used as the base, and to it army mapmakers added, by hand, cultural data on Virginia, a new map title, forts, batteries, and rifle pits, as well as the military roads built to link them (LC Civil War Maps no. 676).

Mapping of Northern Virginia

Occupancy of key positions in Virginia enabled Federal officials to begin the first major mapping project of the war. In June 1861, on orders from Winfield Scott, General in Chief of the Army, two field parties made up of U.S. Coast Survey personnel and under the direction of H.L. Whiting, the survey's "most experienced field assistant," 3 began a 38-square-mile plane table survey of the secured part of northern Virginia. Transportation and protection were provided by army detachments, and the actual map itself was compiled in the Topographical Engineers Office at the Division Headquarters of Gen. Irvin McDowell at Arlington, Virginia. This cooperative undertaking involving both Coast Survey and army personnel was to be the pattern followed throughout the war. Coast Survey assistants provided valuable service to armies in the field as well as to the naval squadrons blockading Southern bays, harbors, and ports.

Work on the map was interrupted in July when Federal troops in northern Virginia suffered a jolting defeat at Manassas, Virginia (Bull Run). The need for an accurate map of northern Virginia was reinforced by the Union disaster only a few miles from the capital city. Work was quickly resumed on this key map and, under orders from Gen. George McClellan, who had assumed command of the armies around Washington, the area covered by the survey was significantly expanded. The first edition of the map was "engraved on stone" and issued on January 1, 1862.

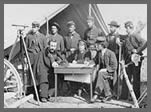

Detail of [Portrait of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, officer of the Federal Army, and his wife, Ellen Mary Marcy]

A second edition incorporating corrections "from recent surveys and reconnaissances under direction of the Bureau of Topographical Engineers" was published on August 1, 1862, only 28 days before the second Battle of Manassas, Virginia.

Published at the scale of one inch to one mile (1:63,360), field assistant Whiting commented that "The detailed survey shows all the important topographical features of the country which it embraces; the main roads, by-roads, and bridle-paths; the woods, open grounds, and streams; houses, out-buildings, and fences; with as close a sketch of contour as the hidden character of the country would allow--producing in all a map by which any practicable military movement might be studied and planned with perfect reliability."4 This was the first detailed map of northern Virginia to be compiled and published, and it remains today an essential cartographic tool for the study of that region at midnineteenth century (LC Civil War Maps nos. 466-470).

Field Reconnaissance

Federal authorities used every means at their disposal to gather accurate information on the location, number, movement, and intent of Confederate armed forces. Army cavalry parties were constantly probing the countryside in search of the enemy's picket lines; travelers and peddlers were interrogated; Southerners sympathetic to the Union were contacted and questioned; and spies were dispatched into the interior to obtain information. The army also turned to a new device for gathering information, the stationary observation balloon. Early in the war a balloon corps under the direction of Thaddeus Lowe was established and attached to the Army of the Potomac. Although used chiefly for observing the enemy's position in the field, the balloon was also successfully employed for the making of maps and sketches. Aeronaut John La Montain made one of the earliest sketches from the platform of a balloon. Dated August 10, 1861, the simple sketch shows the location of Confederate tents and batteries at Sewall's Point, Virginia (LC Civil War Maps no. 654).

The Geography and Map Division has an interesting reconnaissance map prepared during the crucial Seven Days' battles of the Peninsula Campaign. It was compiled under the alias of E.J. Allen, by the famous nineteenth-century detective Allan Pinkerton, with the assistance of one of his operatives, John C. Babcock. Pinkerton, who earlier had established the U.S. Secret Service in Washington, served as McClellan's chief of intelligence during the Peninsula Campaign. Based in part on the prewar map of Henrico County by James Keily, Pinkerton and Babcock's map includes a wealth of up-to-date military information, such as Confederate batteries, Federal lines, and Federal cavalry and infantry pickets. The faded sunprint in the Geography and Map Division was initially prepared on May 31, 1862, corrected on June 20, and again on July 22 (LC Civil War Maps no. 620).

Detail of [Antietam, Md. Allan Pinkerton, President Lincoln, and Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand; another view].

Another badly faded issue of this map is preserved in the Library's Manuscript Division.5 This photocopy, dated June 6, 1862, is particularly noteworthy because it has been annotated in red and black inks to show information obtained from two tethered balloons (LC Civil War Maps no. 619.5). A note written by Thaddeus Lowe at the bottom of the map reads as follows:

Balloon Camp, June 14th 1862.

The red lines represent some of the most important earth works seen this

morning & are located as near as possible, as is also the camps in black ink.

As soon as I can get an observation from the Mechanicsville Balloon I can make

many additions to this map.

[Signed] T.S.C. Lowe

Detail of [Antietam, Md. Seated: R. William Moore and Allan Pinkerton. Standing: George H. Bangs, John C. Babcock, and Augustus K. Littlefield].

Map Production

Field and harbor surveys, topographic and hydrographic surveys, reconnaissances, and road traverses by Federal mappers led to the preparation of countless thousands of manuscript maps and the publication of maps and charts in unprecedented numbers. The Superintendent of the Coast Survey in his annual report for 1862 noted that "upwards of forty-four thousand copies of printed maps, charts, and sketches have been sent from the office since the date of my last report--a number more than double the distribution in the year 1861, and upwards of five times the average annual distribution of former years. This large and increasing issue of charts within the past two years has been due to the constant demands of the Navy and War Departments, every effort to supply which still continues to be made."6 By 1864, the number of maps and charts printed during the year reached 65,897, of which more than 22,000 were military maps and sketches.7 Large numbers of maps also were compiled and printed by the Army's Corps of Engineers. The Chief Engineer reported that in 1864, 20,938 map sheets were furnished to the armies in the field, and in the final year of the war this figure grew to 24,591.8

The great demand for maps and charts could not have been met were it not for the introduction of two lithographic presses in the Coast Survey office in 1861. Previously, the Survey, like most other Federal mapping agencies, was dependent upon the laborious and time-consuming process of printing maps from engraved copper plates. Because of the ease in transferring manuscript data to stone, the versatility of the process, and the speed of the lithographic presses, reliance on lithography grew rapidly during the war. By 1863, the Superintendent reported that "Two lithographic presses have been kept in constant operation throughout the year, and such has occasionally been the pressure on the division that it has been found necessary to employ other lithographic establishments in the execution of special jobs."9 To help satisfy the Federal government's printing demands, commercial firms such as Julius Bien and Company in New York, and Bowen and Company in Philadelphia were hired to print the needed maps.

Detail of [Chattanooga, Tenn., vicinity. Tripod signal erected by Capts. Dorr and Donn of U.S. Coast Survey at Pulpit Rock on Lookout Mountain]

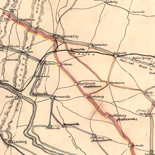

The development and growing sophistication of the Union mapping effort was apparent in 1864 when it became possible for Coast Survey officials to compile a uniform, ten-mile-to-the-inch base map described by the Superintendent as "the area of all the States in rebellion east of the Mississippi river, excepting the back districts of North and South Carolina, and the neutral part of Tennessee and to southern Florida, in which no military movements have taken place."10 Moreover, as the Superintendent noted, the map was placed on lithographic stones so that "any limits for a special map may be chosen at pleasure, and a sheet issued promptly when needed in prospective military movements."11 During the final two years of the conflict, numerous regional base maps at ten miles to the inch and showing boundaries, relief, place names and lines of transportation were issued by the Coast Survey. Some were printed without map titles, such as the map of eastern Tennessee and environs (LC Civil War Maps no. 75.8), while others bore map titles, such as the map of "North Carolina & South Carolina" (LC Civil War Maps no. 305a.4).

Relief Representation

Throughout the war military publishing authorities continued to favor the use of hachures to depict relief on published maps. Although contour lines or "horizontal curves," as they were sometimes called, were used increasingly by topographic engineers in their field surveys, the technique apparently was not considered satisfactory for the finished or published map. Col. William E. Merrill, for example, submitted to the Engineer Department a topographic survey of the battlefield of Chickamauga, Georgia on which relief is represented by contour lines at 20-foot intervals and layer tints. In an explanatory note, Merrill wrote that "This map was prepared as a guide to the draughtsman who might be employed to prepare the complete map of the battle of Chicamauga [sic]. By carefully studying the contour lines and tints on this map an accurate map with hachures may be made of the ground" (LC Civil War Maps no. 157.4).

The map of the "Approaches to Grand Gulf. From a Topographical & Hydrographical Survey by F.H. Gerdes" is an example of a printed map in which the publisher favored hachures over contours to depict the topography of the area. On file in the Geography and Map Division is a photocopy of a preliminary version of the Grand Gulf map with annotations in ink and pencil (LC Civil War Maps no. 271). Believed to be Gerdes's field copy, it shows that he elected to indicate relief by contour lines rather than by hachures. By the time the map was issued, however, the publisher had converted this information into the more conventional hachure technique with which the nonexpert was more familiar (LC Civil War Maps no. 270).

Richard W. Stephenson, Civil War Maps

References

- The Corps of Topographical Engineers was incorporated

into the Corps of Engineers on March 3, 1863.

Back to Text - U.S. Army, Corps of Engineers, Report on the

Defenses of Washington to the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, by Bvt. Maj. Gen. J. G.

Barnard (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1871), p. 33.

Back to Text - U.S. Coast Survey, Report of the Superintendent of

the Coast Survey, showing the Progress of the Survey during the Year 1861

(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1862), p. 39.

Back to Text - Ibid., p. 40.

Back to Text - Thaddeus Lowe Papers, American Institute of Aeronautics

and Astronautics, Aeronautic Archives, container 82, "Sketches and Drawings" folder,

Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Back to Text - U.S. Coast Survey, Report of the Superintendent of

the Coast Survey, Showing the Progress of the Survey During the Year 1862

(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864), p. 15.

Back to Text - U.S. Coast Survey, Report of the Superintendent of

the Coast Survey, Showing the Progress of the Survey During the Year 1864

(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1866), p. 38.

Back to Text - U.S. War Department, Annual Report of the

Secretary of War [1864] (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1865), p. 31,

and U.S. War Department, Annual Report of the Secretary of War [1865]

(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1866), v.2, p. 919.

Back to Text - U.S. Coast Survey, Report of the Superintendent of

the Coast Survey, Showing the Progress of the Survey During the Year 1863

(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864), p. 137.

Back to Text - U.S. Coast Survey, Report of the Superintendent . . ., 1864, p.

111.

Back to Text - Ibid.

Back to Text

Confederate Mapping

The Confederate Army had difficulty throughout the war in supplying its field officers with adequate maps. The situation in the South was acute from the beginning of hostilities because of the lack of established government mapping agencies capable of preparing large-scale maps, and the inadequacy of reprinting facilities for producing them. The situation was further complicated by the almost total absence of surveying and drafting equipment, and the lack of trained military engineers and mapmakers to use the equipment that was available.

Their ignorance of the land about them during the Seven Days' battles in 1862 was bitterly described by Gen. Richard Taylor. "The Confederate commanders," he wrote, "knew no more about the topography of the country than they did about Central Africa. Here was a limited district, the whole of it within a day's march of the city of Richmond, capital of Virginia and the Confederacy, almost the first spot on the continent occupied by the British race, the Chickahominy itself classic by legends of Captain John Smith and Pocahontas; and yet we were profoundly ignorant of the country, were without maps, sketches, or proper guides, and nearly as helpless as if we had been suddenly transferred to the banks of the Lualaba [Congo River]."[1]

Confederate officers, of course, were not alone in their lack of adequate maps. During the Peninsula Campaign which culminated in the Seven Days' battles, Union Army commanders were also hard pressed to obtain reliable maps. Gen. George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, lamented that "Correct local maps were not to be found, and the country, though known in its general features, we found to be inaccurately described, in essential particulars, in the only maps and geographical memoirs or papers to which access could be had; erroneous courses to streams and roads were frequently given, and no dependence could be placed on the information thus derived. This difficulty has been found to exist with respect to most portions of the State of Virginia, through which my military operations have extended. Reconnoisances [sic], frequently under fire, proved the only trustworthy sources of information."[2]

On assuming command of the Army of Northern Virginia from the wounded Joseph E. Johnston on June 1, 1862, Gen. Robert E. Lee, a former army engineer himself, took prompt action to improve the Confederate mapping situation. Five days after his appointment, Lee assigned Captain (later Major) Albert H. Campbell to head the Topographical Department. Within a few days, two or three field parties were organized and dispatched into the countryside around Richmond to collect the data for an accurate map of the environs of the Confederate capital. "The field work was mapped as fast as practicable," Campbell wrote, "but as the army soon changed its location, more immediate attention was given to other localities. Therefore, this map in question was dated 1862-3: it was not available as complete until the spring of 1863."[3]

As quickly as possible, other survey parties were formed and sent into Virginia counties in which fighting was likely to occur. Based on the new information, Confederate engineers under the direction of Campbell and Maj. Gen. Jeremy F. Gilmer, Chief of Engineers, prepared detailed maps of most counties in eastern and central Virginia. The maps were drawn in ink on tracing linen and filed in the Topographical Department in Richmond.

Prepared most often on a scale of 1:80,000, with a few at 1:40,000, each county map generally indicated boundaries, villages, roads, railroads, relief (by hachures), mountain passes, woodland, drainage, fords, ferries, bridges, mills, houses, and names of residents. These maps today are sometimes referred to as the Gilmer-Campbell maps or the "Lost War Maps of the Confederates," the latter term being applied because their whereabouts was unknown until many years after the war. This was also the title of Albert Campbell's revealing article published in the January 1888 issue of Century Magazine.[4]

Lt. C. S. Dwight's "Map of Albemarle County from Surveys and Reconnaissances" is typical of the maps made by Confederate engineers in Virginia. This well-executed map, drawn in ink on a sheet of tracing linen measuring 80 by 68 cm. was approved by Albert H. Campbell on June 15, 1864 (LC Civil War Maps no. 520a.8).

Introduction of Photography

Initially, when requests were received in the Topographical Department for maps of a particular area, a draftsman was assigned to make a tracing of the file copy. But, "So great was the demand for maps occasioned by frequent changes in the situation of the armies," Campbell noted, "that it became impossible by the usual method of tracings to supply them. I conceived the plan of doing this work by photography, though expert photographers pronounced it impracticable, in fact impossible . . . . Traced copies were prepared on common tracing-paper in very black India ink, and from these sharp negatives by sun-printing were obtained, and from these negatives copies were multiplied by exposure to the sun in frames made for the purpose. The several sections, properly toned, were pasted together in their order, and formed the general map, or such portions of it as were desired; it being the policy, as a matter of prudence against capture to furnish no one but the commanding general and corps commanders with the entire map of a given region."[5] Jedediah Hotchkiss, Topographic Engineer with the Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, received from the Confederate Topographical Engineers Office the following formula and instructions for photocopying maps:

Formula of Sanxay used in copying maps in Topl.

Eng. Office, C.S.A. (from Sanxay)

Formula for Capt. Hotchkiss

Silver Bath

Nit. Silver 60 gr to 1 oz of water

Con Amonia 1 drop to the oz of water

float the paper on the Silver Solution then dry,

after printing

Wash the print about 15 minutes in fair water,

then immerse in Toning Bath

Bi Carb Soda Saturate Solution

Cloride Gold 15 gr to 1 oz water

nutralize [sic] gold solution with soda solution

(try with litmus paper)

Wash prints in fair water 15 minuets [sic] and then

immerse in Fixing Solution

Hypo Soda 1 lb to 1 gal water about 15 minuets [sic]

Wash in running water about 12 hours, dry and the

prints are finished.

Take the map to be copied and lay it on a glass in printing frame the back of map to the glass. Place the sencitised [sic] paper face to face on the map. Put the back in the frame and wedge it up tight. Expose it to the sun and make a dark print (that is very intense). Tone & fix, that will be the negative. Print in the same way from the negative to make the positive.[6]

By 1864, therefore, the Confederate Topographical Department was capable of supplying field officers with photoreproductions and thereby able to avoid making time-consuming tracings or costly lithographic prints. The resulting photocopies, although crude by today's standards, were quite legible and were frequently cut and mounted in sections on cloth to fold to a convenient size to fit an officer's pocket or saddle bag. Because of the lack of printing presses and paper, maps remained in relatively short supply. The manuscript and photoreproduced copies that were available, however, were the equal in quality to the more numerous maps by Federal authorities. Campbell's "Map of the Vicinity of Richmond and Part of the Peninsula" is typical of the maps prepared by the Confederate engineers for the use of the field commanders. Prepared in 1864, the map was photographed, hand colored, sectioned, and mounted on cotton muslin to fold to 16 by 13 cm. (LC Civil War Maps no. 624-626).

All the maps used by the Federal and Confederate forces of course were not compiled and produced at headquarters in Washington or Richmond. On both sides, armies, corps, and divisions in the field had topographical engineers assigned to their staffs whose role was to gather information for the preparation of maps. Many significant reconnaissance maps were compiled in the field, detailed battlefield maps were prepared, and base maps supplied by headquarters were vastly improved as new information was collected.

Richard W. Stephenson, Civil War Maps

References

- Richard Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction:

Personal Experiences of the Late War, Richard B. Harwell, ed. (New York:

Longmans, Green & Co., 1955), p. 99.

Back to Text - George B. McClellan, Report on the Organization

and Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac (New York: Sheldon & Co., 1864), p.

157.

Back to Text - Albert H. Campbell, "The Lost War Maps of the

Confederates," Century Magazine 35 (January 1888): 480. A copy of Campbell's

map entitled "Map of the Battle-Grounds in the Vicinity of Richmond, Va. . . . 1862

and 3," is reproduced in the U.S. War Department's Atlas to Accompany the

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: Government

Printing Office, 1891-1895), plate xx-1.

Back to Text - The Gilmer-Campbell maps are a valuable record of

Virginia's rural landscape during the Civil War. Fortunately, many of the original

manuscript maps are extant today. A few are preserved in the Library of Congress,

while others are in the Virginia Historical Society and the Museum of the Confederacy

at Richmond, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and the University of North

Carolina Library, Chapel Hill.

Back to Text - Campbell, "The Lost War Maps of the Confederates," p.

480.

Back to Text - Filed with Hotchkiss's "Report of the Camps, Marches

and Engagements, of the Second Corps, A.N.V. and the Army of the Valley Dist., of the

Department of Northern Virginia; during the Campaign of 1864 . . ." (Hotchkiss Map

Coll. no. 8).

Back to Text

Field Mapping

Although all successful field commanders realized the necessity of clearly understanding the lay of the land over which they were moving or fighting, some placed a higher value on mapping activities than others. Two eminent commanders that fall in this category are Generals William T. Sherman and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson.

General William Tecumseh Sherman

On March 18, 1864, Sherman became Commanding General of the Military Division of the Mississippi, succeeding Ulysses S. Grant, who became General in Chief of the Armies of the United States. Grant immediately ordered Sherman "to move against Johnston's army, to break it up, and to get into the interior of the enemy's country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can against their war resources."[1] Sherman, with more than one hundred thousand men under his command from the Armies of the Cumberland, Tennessee, and the Ohio, immediately began preparations for what became known as the Atlanta Campaign.

The Topographical Department of the Army of the Cumberland, under the direction of Col. William E. Merrill, was chiefly responsible for providing the maps necessary for the Atlanta Campaign. Thomas B. Van Horne in his History of the Army of the Cumberland (1875) notes that "The army was so far from Washington that it had to have a complete map establishment of its own. Accordingly, the office of the chief topographical engineer contained a printing press, two lithographic presses, one photographic establishment, arrangements for map-mounting, and a full corps of draughtsmen and assistants."[2]

The lithographic presses were invaluable for quickly providing multiple copies of a map. However, the weight of the presses and stones made transporting them difficult, necessitating that they remain in a central depot near the front lines. As Van Horne points out, the topographic engineers in the field had available to them a mobile "fac-simile [sic] photoprinting device invented by Captain Margedant, chief assistant. This consisted of a light box containing several india-rubber baths, fitting into one another, and the proper supply of chemicals. Printing was done by tracing the required map on thin paper and laying it over a sheet coated with nitrate of silver. The sun's rays passing through the tissue paper blackened the prepared paper except under the ink lines, thus making a white map on black ground. By this means copies from the drawing-paper map could be made as often as new information came in, and occasionally there would be several editions of a map during the same day. The process, however, was expensive, and did not permit the printing of a large number of copies; therefore these maps were only issued to the chief commanders."[3] The map of the environs of Resaca, Georgia, is an example of a quickly made field map produced by the Margedant photoreproduction process. Printed on May 13, 1864, it shows the critical position of the Army of the Tennessee at Snake Creek Gap, Georgia (LC Civil War Maps no. S102).

In preparation for the coming campaign, the Topographical Department began the compilation of an accurate campaign map of northern Georgia. The best available map was enlarged to the scale of an inch to the mile.[4] According to Van Horne, this was then "elaborated by cross-questioning refugees, spies, prisoners, peddlers, and any and all persons familiar with the country in front of us. It was remarkable how vastly our maps were improved by this process. The best illustration of the value of this method is the fact that Snake Creek Gap, through which our whole army turned the strong positions at Dalton and Buzzard Roost Gap, was not to be found on any printed map that we could get, and the knowledge of the existence of this gap was of immense importance to us."[5]

Two days before the Atlanta Campaign began, the Topographical Department was informed of the date of advance. As Van Horne notes, the single copy of the map of northern Georgia over which the Topographical Department had been laboring "was immediately cut up into sixteen sections and divided among the draughtsmen, who were ordered to work night and day until all the sections had been traced on thin paper in autographic ink. As soon as four adjacent sections were finished they were transferred to one large stone, and two hundred copies were printed. When all the map had thus been lithographed the map-mounters commenced their work. Being independent of sunlight the work was soon done--the map-mounting requiring the greatest time; but before the commanding generals left Chattanooga, each had received a bound copy of the map, and before we struck the enemy, every brigade, division, and corps commander in the three armies had a copy."[6] Entitled "Map of Northern Georgia made under the direction of Capt. W. E. Merrill, Chief Topl. Engr.," the finished map measures 94 by 88 cm. It is lightly hand colored and indicates below the title and scale that it was "Lith. and printed at Topl. Engr. Office, Dept. Cumbd., Chattanooga, Tenn. May 2d, 1864." For ease of carrying in the field, the map was cut into 24 sections and mounted on cloth to fold to 16 by 23 cm. Pasted to the cloth mounting were cardboard covers to protect the map when folded (LC Civil War Maps no. S29-S30).

In addition to the standard edition of the campaign map lithographed on paper, it was also printed directly on muslin and issued in three parts. Van Horne points out that this was mainly for the convenience of the calvary, "as such maps could be washed clean whenever soiled and could not be injured by hard service."[7] Each section of the cloth map is entitled "Part of Northern Georgia" and was printed from one of the lithographic stones used for the standard campaign map. The superb work of the Topographic Department, Army of the Cumberland, led Van Horne to conclude "that the army that General Sherman led to Atlanta was the best supplied with maps of any that fought in the Civil War."[8] (LC Civil War Maps nos. 129.75, S22, and S31).

Preserved in the Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, is a collection of 210 maps and three atlases belonging to Gen. William T. Sherman. This important cartographic collection, brought together from three separate acquisitions by the Library, includes both printed and manuscript maps, as well as contemporary photocopies. Many of the items were used by the general and his staff during the march on Atlanta in 1864. Represented are small-scale regional maps, maps indicating troop positions and fortifications, and reconnaissance maps. The latter were issued to topographical engineers on field assignment who were then required to plot new data and directed to return the reconnaissance maps to headquarters as soon as possible. Annotations were usually made in red to show additional roads, railroads, fortifications, and dwellings. One such reconnaissance map made as the army moved toward Atlanta is entitled "Part of De Kalb and Fulton County, Ga." (LC Civil War Maps no. S77). The base map was compiled and printed in Marietta, Georgia, on July 5, 1864, by the Topographical Engineer's Office, Department of the Cumberland. Instructions on the map direct topographical engineers "to return as soon as possible one copy of this land map with all the information they are able to obtain, to this office. Corps Engineers will cause a speedy compilation." The copy of the map in Sherman's possession has annotations apparently made by Lt. Harry C. Wharton, an engineer in the Army of the Cumberland.

Also issued to field parties during the campaign was a similar printed base map covering the area south of Atlanta. The lithographed copy preserved as number 24 in the Sherman Map Collection has been revised by the use of an overlay covering the East Point-Rough and Ready area. The overlay has a significant number of revisions of the original base map, including the realignment of lines of communication and the repositioning of the towns of East Point and Rough and Ready. In addition, numerous names of residents and some relief have been added. By the use of this simple expediency, the Topographical Engineer's Office was able to get the revised data to the field parties without having to redraft and print the entire map.

General Thomas J. Jackson

After distinguishing himself in June 1861 at the first battle of Manassas where he earned the nickname "Stonewall," Thomas J. Jackson was promoted to major general and assumed command of the Confederate forces protecting the Shenandoah Valley. The valley was of immense strategic importance to the Confederate cause because it provided needed agricultural products for the South and a natural transportation route for invading the North. Jackson's defense of the valley provides an excellent example of the significance of skilled field mapping.

At the beginning of March 1862, a schoolmaster from Staunton, Virginia, named Jedediah Hotchkiss joined Jackson's staff as topographical engineer. Realizing his need for a better understanding of his surroundings, Jackson ordered Hotchkiss to "make me a map of the Valley, from Harper's Ferry to Lexington, showing all the points of offence and defense in those places."[9] The resulting comprehensive map, drawn on tracing linen at the scale of 1:80,000 and measuring 254 by 111 cm., was of significant value to Jackson and his staff in planning and executing the Valley Campaign in May and June 1862 (LC Civil War Maps no. H89). Conducted against numerically superior forces, the Valley Campaign is considered "one of the most brilliant operations of military history."[10] The success of his actions and movements so disturbed Federal planning that large numbers of troops were withheld from General McClellan's advance on Richmond. Conceivably, without the aid of superior maps, Jackson's diversionary efforts would not have succeeded and McClellan's movement on Richmond would have had a different ending.

The map of the Shenandoah Valley constructed for Jackson is preserved with the rest of Jedediah Hotchkiss's map collection in the Library's Geography and Map Division.[11] This is one of the finest collections of Confederate maps in existence today. In addition to the master map, there are countless sketches, reconnaissance maps, county maps, regional maps, and battle maps. Of particular interest is his sketchbook with over one hundred pages of drawings recording roads and distances, topographic features, and the location of dwellings and names of occupants (LC Civil War Maps no. H1). Much of the information recorded in the sketchbook was later transferred to his finished maps. Hotchkiss annotated the cover of the sketchbook as follows:

This volume is my field sketch book that I used

during the Civil War. Most of the sketches were made

on horseback just as they now appear. The colored pencils

used were kept in the places fixed on the outside of the other cover.

These topographical sketches were often used in

conferences with Generals Jackson, Ewell and Early.

The cover of this book is a blank Federal

commission found in Gen. Milroy's quarters at Winchester.

[signed] Jed Hotchkiss.

Richard W. Stephenson, Civil War Maps

References

- William Tecumseh Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman by

Himself (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1957), 2 vol. in 1, v. 2, p.

26.

Back to Text - Thomas B. Van Horne, History of the Army of the Cumberland (Cincinnati:

Robert Clarke & Co., 1875), vol. 2, p. 456.

Back to Text - Ibid., pp. 456-457.

Back to Text - The base map used was James R. Butts's "Map of the State of Georgia" (1859). See

R. W. Stephenson, "Mapping the Atlanta Campaign," Special Libraries Association,

Geography and Map Division, Bulletin, 127 (March 1982): pp. 8-9.

Back to Text - Van Horne, History of the Army of the Cumberland, p. 457.

Back to Text - Ibid., pp. 457-458.

Back to Text - Ibid., p. 458.

Back to Text - 8.Ibid., p. 358.

Back to Text - Jedediah Hotchkiss, Make Me a Map of the Valley: The Civil War Journal of

Stonewall Jackson's Topographer, ed. by Archie P. McDonald, foreword by T. Harry

Williams (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press [1973], p. 10.

Back to Text - Mark Mayo Boatner III, The Civil War Dictionary (New York: David McKay

Co., Inc., 1959), p. 739.

Back to Text - For an article about the acquisition and contents of the collection, see Clara

Egli LeGear, "The Hotchkiss Map Collection," The Library of Congress Quarterly

Journal of Current Acquisitions 6 (November 1948): 16-20.

Back to Text

Official Battlefield Maps

When time permitted topographical engineers in both armies were called upon to prepare accurate, detailed maps of the fields of battle. Cultural and topographical features were carefully shown and the position of troops and batteries was depicted in detail. Many of these maps were used to illustrate official reports of the field commanders or were sent back to headquarters in Washington and Richmond for placement in the official files. Excellent examples of maps made to accompany an official account are those prepared by Hotchkiss to illustrate the "Report of the Camps, Marches & Engagements, of the Second Corps, A.N.V., Army of the Valley Dist. and of the Department of Northern Va., during the Campaign of 1864." Both the handwritten narrative and the accompanying manuscript atlas containing 59 campaign and battle maps are preserved in the Hotchkiss Map Collection. The maps were carefully executed in pen and ink and watercolors by Hotchkiss and his assistant Sampson B. Robinson between November 1864 and March 1865 (LC Civil War Maps no. H8).

Federal mapping authorities, aware of the need for good public relations, made an occasional attempt to inform the populace on the progress of the war. In May 1862, for example, the U.S. Coast Survey issued the first of at least four editions of a "Historical Sketch of the Rebellion," which depicted the "limits of loyal states in July, 1861," the "limits occupied by United States forces March 1st 1862," and the "limits occupied by United States forces May 15th 1862" (LC Civil War Maps no. 34). For the most part, however, the responsibility for keeping the public informed as the war unfolded rested with the private sector and not the government.

Richard W. Stephenson, Civil War Maps

Commercial Mapping

Throughout the American Civil War, commercial publishers in the North and to a lesser extent in the South produced countless maps for an eagerly awaiting public in need of up-to-date geographical information. Few families were without someone in the armed forces serving in a little-known place in the American South. Maps, therefore, were not only important sources of information, but also satisfied the patriotic impulses of the populace. Publishers in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and Boston quickly became aware of this profitable market and began to issue maps in quantities undreamed of before the war.

Northern Publishers

One of the earliest maps, copyrighted by M. H. Traubel of Philadelphia less than a month after the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, is entitled "Pocket Map of the Probable Theatre of the War." The compiler of the map, civil engineer G. A. Aschbach, accurately anticipated that the principal seat of war in the East would be Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. To assist the map user, Aschbach underlined camps and forts in red and prominent places in blue (LC Civil War Maps no. 1).

Many of the early maps were little more than general maps depicting railroads, rivers, state boundaries, cities and towns, and perhaps a few well-known forts. "Lloyd's Map of the Southern States" for example, produced and sold by James T. Lloyd, publisher of Lloyd's American Railroad Weekly, was very popular and was issued in each of the first three years of the war. Although Lloyd included little specific information about the war on his map, he issued it after July 12, 1861, with an extensive "gazetteer of the Southern States" printed on the verso.[1]

Lloyd's maps are especially interesting today for the informative advertisements and testimonials that the publisher unabashedly included on them. One advertisement, for example, called attention to Lloyd's "$100,000 Topographical Map of the State of Virginia," priced at 25 cents a copy, and about which the publisher noted, "we intend to sell 3,000,000 copies of this great map" (LC Civil War Maps no. 14.25).

Although it is doubtful that Lloyd sold so many copies, his map of Virginia was indeed popular with the public with editions appearing in 1861, 1862, and 1863. Lloyd based his first edition on the Wood-Be nine-sheet map of Virginia initially published in 1826 (mistakenly cited by Lloyd as 1828) and revised in 1859 by Ludwig von Buchholtz. To enhance his map over his competitors, Lloyd called his the "official map" and included a note on the 1861 edition that "This is the only map used to plan campaigns in Virginia by Gen. Scott." (LC Civil War Maps no. 450).

The 1862 edition announced that it had been "corrected from surveys made by Capt. W. Angelo Powell, of the U.S. Topographical Engineers." Since the aged Gen. Winfield Scott had been forced into retirement by then, Lloyd now noted that "This is the only map used to plan campaigns in Virginia by Gen. McClellan." (LC Civil War Maps no. 465.1).

During the war, James Lloyd carried on an acrimonious dispute with another New York publisher, H. H. Lloyd and Company. On his map of the Mississippi River issued in 1863, James Lloyd cautioned the public "against another `Lloyd' by which name he hopes to deceive the public with spurious `Lloyd Maps.' This man's maps are engraved coarsely on wood and very erroneous. He follows us with an imitation of every map we issue." H. H. Lloyd's map of the Mississippi River, engraved on wood by Waters and Company (LC Civil War Maps no. 37.2), is indeed inferior in appearance and content to James Lloyd's very detailed, nicely lithographed map (LC Civil War Maps no. 41). It is difficult to determine, however, whether or not the former purposely traded on the name of the latter.

While it is true that H. H. Lloyd's maps are somewhat coarse, they are good examples of wood-engraved maps, and they are generally clear and easy to read. The 1865 edition of his "New Military Map of the Border & Southern States," for example, emphasizes battlefields by red underlining, and strategic places by red dots. Furthermore, it effectively delineates in red the "territory held by Rebels April 1st, 1865," in yellow, the "territory gained from Rebels since January 1st, 1862," and in blue, "Sherman's march from Chattanooga" (LC Civil War Maps no. 71).

To enhance sales, some publishers went to great lengths to make their maps as distinctive from those of their competitors as possible. For instance, Prang and Company of Boston conceived the idea of publishing a "War Telegram Marking Map" on which one could follow the events of the war. This popular map, issued in at least six editions, was published on a large scale to permit the marking of "change of position of the Union forces in red pencil and the rebel forces in blue on the receipt of every telegram from the seat of war." The map was accompanied by colored pencils which the publisher noted "should be used with a light hand to enable obliterating the marks with the aid of a little soft bread, if found necessary. These peculiarities combined with extreme cheapness will make this map a welcome companion to every person interested in the pending struggle of our nation." (LC Civil War Maps no. 465.75).

Prang's map, primarily designed for the use of the citizen back home, included an advertisement for "Agents wanted to sell this map in all parts of the country." Some Northern publishers also aimed their maps at the lucrative market comprising the officers and enlisted men serving in the Union armed forces. Boston publisher John H. Bufford's map of Georgia and South Carolina, entitled "Genl. Sherman's Campaign War Map," and his map of the environs of Richmond, Virginia, entitled "Genl. Grant's Campaign War Map," both carried notes that "Agents wanted in all the camps and throughout the loyal states to sell this map, pictures & photographs of every description." (LC Civil War Maps nos. 124 and 623). Bufford's maps are particularly interesting because of their use of a letter-number grid reference system, described by the publisher as follows:

The horizontal and upright lines [of the map grid] represent five miles square. By referring to the number on the left and to the letter on the base, any point may be found to show the locality of the Union armies. By this method those in the army are enabled to inform their friends of the movements of their companies and their location and will also serve as a journal to each soldier.

As another means of maximizing sales, publishers sometimes combined various kinds of illustrative data. In 1861, for example, H. H. Lloyd published a brightly colored wood engraving featuring "Military Portraits, Map of the Seat of War, Uniforms, Arms, &c." Here the map of the "Western Border Lands" occupied only a third of the printed sheet and definitely was of secondary importance to the portraits of the war heroes (LC Civil War Maps no.12.7).

Other publishers depended on bold titles emblazoned across the sheet to catch the citizen's attention and hopefully to sell the map. The title to the W. H. Forbes and Company's unimaginative map of Central Virginia certainly "sells" the map. It reads in part: "Theater of the War: A Complete Map of the Battle Ground of Hooker's Army!!" (LC Civil War Maps no. 479.5).

The New York and Washington publisher Charles Magnus sold his popular map of "One Hundred & Fifty Miles Around Richmond" separately and as part of a "Half Dollar Portfolio." Included with the map in this "Glorious Union Packet," as the publisher called it, was a Mirror of Events [i.e., list of battles], 2 illustrated Notesheets, 1 Song Notesheet, 3 illustrated Envelopes, 6 Portraits of Army and Navy Officers, 4 plain Notesheets, 4 plain Envelopes, Penholder, [and] Pen and Lead-pencil" (LC Civil War Maps no. 632.4).

Southern Publishers

Compared to those in the North, publishers in the South produced few maps for the general public, and those that did appear were issued in small numbers. Printing presses and paper, as well as lithographers and wood engravers, were in short supply. The few maps published for sale to the public were invariably simple in construction, relatively small in size, and usually devoid of color. The Confederate imprint, "Map of the Seat of War in Virginia," is representative. Lithographed and published by Blanton Duncan in Columbia, South Carolina, it is dated December 1, 1862, and measures only 37 by 24 cm. (LC Civil War Maps no. 457).

British Publishers

The broad interest among the British in the American Civil War is evidenced by the number of maps produced by some of the major contemporary map publishers of Great Britian--James Wyld, George Philip, Edward Stanford, Bacon and Company in London, and John Bartholomew in Edinburgh. The leading English publisher and seller of maps of the American Civil War was Bacon and Company. By 1862, this firm had published a series of six maps that were known collectively as the "Shilling War Maps." In an advertisement, the firm described the maps as being a "complete series, just published, compiled from authentic sources, and corrected to the present time--showing the railways, forts, and fortifications, population, area, &c, and designating in three colors the boundaries of the Federal, Confederate, and Border Slave States."[2] An example of one of the shilling war maps is "Bacon's Military Map of the United States Shewing the Forts & Fortifications" (LC Civil War Maps no.24). Published in August 1862, it delineates by color the "Free or Non-slaveholding States," the "Border Slave States," and the "Seceded or Confederate States." In addition to publishing maps, Bacon also served as agent in Britain for "Colton's Maps of America, and Complete Series of War Maps." Joseph H. Colton was described by the firm as being for "30 years the largest American Map Publisher."[3]

Propaganda Maps

Although propaganda maps are better known from their use during World Wars I and II, an occasional map of this type was published during the Civil War. Such works are designed to have a maximum psychological impact on the user of the map. The commercial publisher J. B. Elliott of Cincinnati published a cartoon map in 1861 entitled "Scott's Great Snake" which pictorially illustrates Gen. Winfield Scott's plan to crush the South both economically and militarily. His plan called for a strong blockade of the Southern ports and a major offensive down the Mississippi River to divide the South. The press ridiculed this as the "Anaconda Plan," as shown on this map, but this general scheme contributed greatly to the Northern victory (LC Civil War Maps no.11).

Another propaganda map more subtle in appearance, but perhaps just as effective, was Edmund and George Blunt's "Sketch of the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of the United States." The Blunts depicted the "loyal part" of the coast with a heavy (strong) line and the "rebel part" with a thin (weak) line. "This sketch was prepared to show at a glance," explains George Blunt, "the difference in extent of the coasts of the U. States occupied by the loyal men and rebels; its circulation it is believed will have the effect of counteracting the exertions of traitors at home as well as those abroad. Persons having correspondents in Europe would do well to send copies of this sketch to them for circulation" (LC Civil War Maps no. 25).

Battlefield Maps

Countless large-scale maps of battlefields, sieges, and fortifications were produced by commercial firms. Maps of those places and events in the news, particularly those perceived to be victories, guaranteed the publisher a quick profit from a grateful public. To give authenticity to their products, publishers based their maps on "reliable" eyewitness accounts, including those of active participants. For example, the "Map of the Battlefield of Antietam," lithographed by the Philadelphia firm of Duval and Sons, was prepared by Lt. William H. Willcox, Topographical Officer and Additional Aide-de-camp on the staff of Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday, commander of a Union Division at the Battle of Antietam (although better known today as the inventor of baseball). It is interesting to note that this particular copy is inscribed in longhand, "Obtained from Washington & presented to Gen. R. E. Lee by J. E. B. Stuart" (LC Civil War Maps no. 253).

To further expand on the information depicted cartographically, some compilers and publishers added descriptive text to their battle maps. Boston publisher George W. Tomlinson, for example, printed beside his "New Map of Port Hudson" (1863), a one-column "Sketch of Port Hudson and the surrounding batteries" (LC Civil War Maps no. 240). Theodore Ditterline went further, supplementing his unusually shaped oval map of the "Field of Gettysburg" with a 24-page pamphlet describing the battle in detail (LC Civil War Maps no. 331).

Panoramic Maps

Perhaps the finest and most attractive battle map produced during the war was John B. Bachelder's "Gettysburg Battle-Field" (LC Civil War Maps nos. 321-324). Bachelder, an experienced prewar maker of city views, copyrighted his stunning perspective drawing of the field of battle in 1863. In the opening sentence to the accompanying key, Bachelder invited the viewer of his panorama to "Imagine yourself in a balloon, two miles east of the town of Gettysburg, Pa." Not only was the map an artistic success, its accuracy was attested to by no less an authority than the commanding general of the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg, George G. Meade. Reproduced in a facsimile below the map, Meade's handwritten endorsement reads, "I am perfectly satisfied with the accuracy with which the topography is delineated and the position of the troops laid down." The signatures of other field commanders attesting to the "accuracy of our respective commands" are also reproduced in the bottom margin.

Bachelder subsequently became one of the directors of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association and Superintendent of Legends and Tablets. He was responsible for the compilation and publication in 1876 of a very detailed three-sheet map of the battlefield which still is widely used today (LC Civil War Maps no. 325). For his base map, Bachelder used the survey conducted in 1868 and 1869 under the direction of Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and revised in 1973 by P. M. Blake (LC Civil War Maps no. 353.5).

The panoramic map in fact became a popular and effective technique for conveying information about the Civil War. Early in 1861, the skillful artist and lithographer John Bachmann of New York City conceived the idea of producing a series of bird's-eye views of the likely theaters of war. These visually attractive panoramas were easily understood and perhaps more meaningful to a public largely unskilled in map reading. Between 1861 and 1862, Bachmann drew and lithographed at least eight panoramas of the seats of war in Virginia and Maryland, Richmond, North and South Carolina, Florida and part of Georgia, the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, Kentucky and Tennessee, the Gulf Coast in the vicinity of the Mississippi delta, and Texas and part of Mexico (LC Civil War Maps nos. 1.5-3, 23.5, 117.2, 304.5-304.6, 446.8 and 621).

The panoramic map or bird's-eye view also lent itself to colorful depictions of fortifications, hospitals, prisons, and military camps. Excellent representative examples of these are the Baltimore artist and lithographer Edward Sachse's bird's-eye view of Fortress Monroe, Virginia, published and sold in 1861 by Casimir Bohn of Washington, D.C., and Charles Magnus of New York City (LC Civil War Maps nos. 547 and 547.1); "Point Lookout, Md. View of Hammond Genl. Hospital & U.S. Genl. Depot for Prisoners of War," also lithographed by Edward Sachse & Company, and copyrighted in 1864 by George Everett (LC Civil War Maps no.257); and Albert Ruger's "Bird's eye view of Camp Chase, near Columbus, Ohio" (LC Civil War Maps no.318).

The commercial success of bird's-eye views contributed to the widespread adaptation of the technique after the war for the depiction of American and Canadian cities and towns.[4] Albert Ruger, mentioned above, was the first successful postwar artist to produce urban panoramas.[5] His earliest extant drawings were made during the war and are of military camps (LC Civil War Maps nos.318, 319.5 and 660).

City Plans

Commercial publishers also issued an occasional city plan, usually to depict seige or defensive positions. A fine example is civil engineer E. G. Arnold's well-executed map of Washington, D.C., showing the ring of fortifications built to defend the nation's capital from Confederate attack. Because of the sensitive information that Arnold's map contained, the Federal government suppressed its sale shortly after it was published (LC Civil War Maps nos. 674-674.1).

Maps in Newspapers and Journals

Another readily available, yet inexpensive source for maps were the major newspapers and pictorial journals of the day. Maps had occasionally appeared in journals or newspapers since the seventeenth century, but in North America it was not until the American Civil War that they were published with any regularity. At that time, all types of illustrations had reached a new level of popularity. One authority has noted that "Harper's, Leslie's and their lesser rival, the New York Illustrated News . . . employed twenty-seven 'special' or combat artists during the war, and also used the work of more than three hundred identified amateurs as well as of a great many photographers. All together, these three northern weeklies printed nearly six thousand war pictures." [6] Since no inventory or bibliography of maps in newspapers and journals has been compiled, it is not known if any of the combat artists and amateurs also supplied their publishers with sketch maps.

Most newspaper and journal illustrations were printed from woodcuts. This form of reproduction, albeit crude, was inexpensive, reasonably quick to execute, and the woodblocks could be inserted into pages of text and printed on newspaper presses without difficulty. A close-grained hardwood, usually boxwood, cut against the grain, was employed to make the wood engraving. Usually the blocks consisted of several parts tightly bolted together from the rear, a technique invented in England and pioneered in this country by Frank Leslie. After the image was drawn on the block, the parts were separated and distributed among several wood engravers to be worked on simultaneously. Once the carving was completed, place names cast in type metal from a mold (stereotype) were cemented into place, the parts bolted together again, and the whole retouched to insure uniformity. An electrotype metal copy of the woodcut was made and the illustration was ready for printing on the rotary press. The entire process required approximately two weeks to complete from the time the sketch was received by the publisher.

The public was enthralled by pictorial representations of the war, and pictures did much to shape their image and opinion of events and people in the news. Although sometimes lacking the timeliness and artistic merit found in many of the "on the spot" depictions from the battle fronts and military camps, maps nevertheless provided valuable information on the location of places in the news.

Included in the collections of the Library of Congress is a rare example of a woodblock that was used to print a panoramic map published in the March 22, 1862, edition of the New York Illustrated News. Entitled "Scene of the late naval fight and the environs of Fortress Monroe, and Norfolk and Suffolk, now threatened by General Burnside," it was printed from a 25 by 36 cm woodblock composed of 12 separate parts bolted together, each part measuring 13 by 6 cm. The woodblock is now imperfect, with the lower right and left corners missing and some of the individual parts beginning to separate due to age (LC Civil War Maps no. 558.7).

From the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, to the end of the war, maps were occasionally used to illustrate major events or situations. On June 17, 1861, for example, the New York Herald published a timely map entitled "The Seat of War in Virginia" (LC Civil War Maps no. 451.3). This simple woodcut, published a little more than a month before the Union's disastrous defeat at the first Battle of Manassas, depicts strategic cities and towns, transportation routes, fortified positions, and the location and number of Confederate troops at several locations. The map noted, for example, that there were "15,000 troops at Manassas Junction and 15,000 more on the Manassas Gap Railroad" nearby. Executed by Waters and Son, Engravers, New York, it is typical of the maps that appeared throughout the war in newspapers and weekly journals. With minor variations the map was used again on July 27 by the New York Herald. This time, however, it served as the lead map in a special supplement of 34 maps entitled "War Maps and Diagrams" (LC Civil War Maps no.14.65).

The New-York Daily Tribune, not to be outdone by its rival, published "The Tribune War Maps" as a supplement to its daily paper issued on July 30, 1861 (LC Civil War Maps no. 6.2). This section of 17 maps was compiled and engraved on wood by the well-known New York map publisher, George Woolworth Colton. One of the maps in this section that contained some noteworthy strategic information is entitled "Baltimore and Its Points of Attack and Defence." The accompanying explanation notes that "The above drawing, which has been kindly furnished for the The Tribune by an officer of the United States Engineers, exhibits very clearly the points in Baltimore which might be held by military forces whether for purposes of attack or of occupation merely."

In the November 9, 1861, issue of Harper's Weekly a "Map of the Southern States" was published which depicted, among other things, "the harbors, inlets, forts and position of blockading ships" (LC Civil War Maps no. 14.55). An accompanying article entitled "Our War Map" described the map and offered suggestions on its use:

We break through our usual habits in this number, and devote four pages to the publication of a large WAR MAP of the Southern States. Without intending to disparage any of the maps in existence, we think this will be found more reliable, and more useful to the student of the war, than any other we have seen. . . .

Such of our readers as wish to keep "posted" on the progress of the war will do well to paste or otherwise fasten this map on a large board against a wall. A series of pins, alternately black and white, should be inserted at the various points occupied by the National and the Rebel forces, and shifted as often as authentic accounts of movements are received. Care should be taken, however, not to confound newspaper rumors with authentic intelligence. The adoption of this simple expedient will render the otherwise confused accounts of the war in Missouri and Kentucky perfectly intelligible, and will shed a flood of light on the newspaper narratives of current events.

We may refer, in this connection, with a feeling of pride, to the large series of war maps published in this journal. They constitute already a valuable atlas--such a one as would cost, if purchased separately, more than the whole price of Harper's Weekly.[7]

Richard W. Stephenson, Civil War Maps

References

- The "Gazetteer of the Southern States" does not appear

on the verso of the first issue of Lloyd's map copyrighted on July 12, 1861 (LC Civil

War Maps no. 14.2). He did include it, however, with issues published later in 1861

(LC Civil War Maps no. 14.25 and 14.3) as well as in 1862 (LC Civil War Maps no. 29)

and 1863 (LC Civil War Maps no. 41.2).

Back to Text - Advertisement on verso of "Bacon's Military Map of the

United States Shewing the Forts & Fortifications" (London: 1862).

Back to Text - Ibid.

Back to Text - For a list of 1,726 bird's-eye views on file in the

Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, see John R. Hebert and Patrick E.

Dempsey, Panoramic Maps of Cities in the United States and Canada, 2nd ed.

(Washington: Library of Congress, 1984), 181 p. 4,480 views, including those in the

Library of Congress, are listed in the union catalog by John W. Reps entitled

Views and Viewmakers of Urban America (Columbia: University of Missouri

Press, 1984), 570 p.

Back to Text - For a biographical sketch, see "Albert Ruger

(1828-1899)" in Reps, Views and Viewmakers of Urban America, pp. 201-204.

Ruger's personal collection of city views is in the Geography and Map Division,

Library of Congress.

Back to Text - Roger Butterfield, "Pictures in the Papers,"

American Heritage 13 (June 1962): 99.

Back to Text - "Our War Map," Harper's Weekly 5 (November 9,

1861): 706.

Back to Text

Postwar Mapping

At the conclusion of the Civil War, the U.S. War Department published numerous detailed battlefield maps and atlases to document significant military engagements such as those at Antietam, Manassas, Gettysburg, and Atlanta, to name a few. The premier cartographic work of the postwar years, however, is the U.S. War Department's Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (LC Civil War Maps no. 99). Initially issued in 37 parts between 1891 and 1895, it includes 178 plates and constitutes the most detailed atlas yet published on the Civil War. The maps present an especially well-balanced cartographic record of the war because both Union and Confederate sources were used in their compilation. Confederate topographic engineer Jedediah Hotchkiss, for example, supplied the editors with 123 maps for this atlas. Although the original edition of the Atlas to Accompany the Official Records is no longer available for sale from the U.S. Government Printing Office, complete facsimile editions were published in 1958 by Thomas Yoseloff of New York City and in 1978 by Arno Press and Crown Publishers, Inc., New York. The Yoseloff edition was published under the title The Official Atlas of the Civil War and includes an introduction by the noted historian Henry Steele Commager (LC Civil War Maps no. 101). The Arno Press/Crown Publishers edition is entitled The Official Military Atlas of the Civil War, with an introduction by archivist-historian Richard Sommers (LC Civil War Maps no. 101.2).

Clearly, the war created an urgent need for maps that cartographers on both sides worked tirelessly for four years to satisfy. Field survey methods were improved; the gathering of intelligence became more sophisticated; faster, more adaptable printing techniques were developed; and photoreproduction processes became an important means of duplicating maps. The result was that thousands of manuscript, printed, and photoreproduced maps of unprecedented quality were prepared of areas where fighting erupted or was likely to occur. Rarely could an officer have cause to be ignorant of his surroundings, as if he "had been suddenly transferred to the banks of the Lualaba."[1] After peace came in the spring of 1865, another fourteen years were to pass before Congress established the beginnings of a national topographic mapping program with the creation of the U.S. Geological Survey. It was many years, therefore, before modern topographic maps became available to replace those created by war's necessity. The maps of the Civil War are splendid testimony to the skill and resourcefulness of Union and Confederate mapmakers and commercial publishers in fulfilling their responsibilities.

Richard W. Stephenson, Civil War Maps

References

- Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction, p.

99.

Back to Text

![[Plan of Fort Henry and its outworks.]](https://cybercemetery.unt.edu/archive/oilspill/20130117201259im_/http://www.loc.gov/collections/static/civil-war-maps/images/cw0414000.jpg)

![[Detailed map of part of Virginia from Alexandria to the Potomac River above Washington, D.C. 1886].](https://cybercemetery.unt.edu/archive/oilspill/20130117201259im_/http://www.loc.gov/collections/static/civil-war-maps/images/cw0523000.jpg)

![[Topographical map of part of Washington D.C.].](https://cybercemetery.unt.edu/archive/oilspill/20130117201259im_/http://www.loc.gov/collections/static/civil-war-maps/images/cw0688500.jpg)

![Map of the Rappahannock River from [sic] Port Royal to Richards Ferry](https://cybercemetery.unt.edu/archive/oilspill/20130117201259im_/http://www.loc.gov/collections/static/civil-war-maps/images/cw0619600.jpg)

![[Sketch of the battles of Chancellorsville, Salem Church, and Fredericksburg], May 2, 3, and 4, 1863](https://cybercemetery.unt.edu/archive/oilspill/20130117201259im_/http://www.loc.gov/collections/static/civil-war-maps/images/cwh00129.jpg)