| |

|||

|

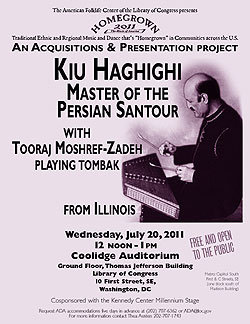

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress presentsThe Homegrown 2011 Concert Series

|

|

Kiu Haghighi begins each day by greeting his beloved instruments in the music room of his Evanston, Illinois home. "Good morning," he says, adding "I love you" before leaving the house to head to the rug gallery from which he earns his livelihood. And at the end of each day, before retiring for the night, he lingers in the music room and says, "thank you for making me so happy." Kiu Haghighi's instruments and his music are as precious to him as the air that he breathes, and failing to acknowledge their contributions to his life on a daily basis is unthinkable.

The santour, Mr. Haghighi's most beloved instrument, came into his life when he was ten years old. He and his family lived in Mashad in northern Iran, and he had been tapping out rhythms on the tombak (Persian drum) from the age of five. Recognizing his talent, his older brother gave him a santour that had been a gift from another family member. Kiu taught himself to play by ear, listening to musicians in the street, on the radio, in cafes, and at family gatherings. A local santour player taught him how to tune his santour. He was asked to play tombak on Radio Mashad, and once the radio director realized that Kiu was also a skilled santour player, he hired Kiu to play santour on a weekly program. He was fourteen.

His family relocated to Tehran when Kiu was seventeen. He was introduced to Abraham Mansouri, the conductor of the National Radio Station in Tehran. Mansouri hired Kiu as a soloist and also taught him to read musical notation. At age nineteen, he was hired as a soloist for the Ministry of Education and Art, where he was also able to continue his study of music theory. He continued performing and teaching in Tehran for the next decade, until he departed for the United States to study architecture. But architecture was ultimately not Kiu's destiny. He began playing in clubs and social gatherings while studying in Cleveland and quickly realized that he had to pursue music full-time. While researching the Persian music scenes in New York and Los Angeles, he was introduced to a woman who encouraged him to visit Chicago. During a performance in Chicago he met his future wife, Maureen, and, happily, Chicago gained a virtuoso santour player and promoter of Persian culture.

Often referred to as the Persian box zither, the santour is strung with between seventy-two and eighty strings, arranged in groups of four. Each set of four strings rests on a movable bridge or kharak. The strings are fixed to hitch pins along the left-hand side and wound around metal pins on the right-hand side, which are then tuned with a tuning key. The right-hand section of the strings corresponds to the bass strings; the left-hand corresponds to the treble strings. The bass strings are made of brass or copper and the trebles of steel. The instrument has a range of three to three-and-a-half octaves (depending on the number of strings), and each string within the four-string unit is tuned to the same pitch.

The body of the santour is trapezoid-shaped and made of hardwood. Mr. Haghighi's santour is made of walnut and is strung with eighty strings. The inside of the resonance box contains several sound posts, whose arrangement plays an important role in the sound quality of the instrument. Two small rosettes on the top panel of the santour help amplify the sound. The santour is played by striking the strings with two light wooden mallets, called mezrab, that are held between the index and middle fingers with the thumb. For today's concert, Mr. Haghighi is playing a santour that was hand-built by a former student.

Persian music is mainly melodic and strictly diatonic. Much of Persian music has no meter but proceeds with a rhythm akin to speech. During the Qajar dynasty (AD 1794- 1925) the collection of melodies in classical Persian music (called Radif) was organized into twelve modes consisting of seven larger modes called dastgahs and five smaller sub-sets called avaz or maqam. Each of these modes is divided into smaller melodic forms called gushehs. A gusheh is a melodic type that typically spans only four or five tones and serves as a mode for improvisation. The gushehs are usually played in an order that fills the lower, middle, and upper portions of the dastgah scale. The dastgahs were transmitted orally until the early twentieth century, when the Radif was codified and placed into staff notation.

The Illinois Arts Council is pleased to present Mr. Kiu Haghighi in concert and to have him represent ethnic and folk arts for the state of Illinois.

Susan Dickson, Director

Ethnic & Folk Arts Program

Illinois Arts Council

The American Folklife Center was created by Congress in 1976 and placed at the Library of Congress to "preserve and present American Folklife" through programs of research, documentation, archival preservation, reference service, live performance, exhibition, public programs, and training. The Center includes the American Folklife Center Archive of folk culture, which was established in 1928 and is now one of the largest collections of ethnographic material from the United States and around the world. Please visit our web site.

The American Folklife Center was created by Congress in 1976 and placed at the Library of Congress to "preserve and present American Folklife" through programs of research, documentation, archival preservation, reference service, live performance, exhibition, public programs, and training. The Center includes the American Folklife Center Archive of folk culture, which was established in 1928 and is now one of the largest collections of ethnographic material from the United States and around the world. Please visit our web site.

| ||||