Tabula Russia

Novaya Gazeta (Moscow, Russia)

Novaya Gazeta (Moscow, Russia)

Posted on December 11, 2006

By Ilya Kriger

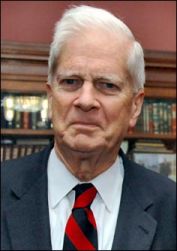

A correspondent of Novaya Gazeta met in St. Petersburg with James Billington, the US Librarian of Congress and a scholar of Russian history and culture, who had come to Russia to take part in the anniversary celebrations of Academician Dmitry Likhachev, a friend of his. James Billington is a historian and a culturologist, which is why we didn’t ask him about current affairs but rather focused on the future.

- How did you take an interest in Russia and its culture?

- I was at school during the Second World War. I wondered how the Russians had managed to defend their country and achieve victory. I asked this question to a Russian immigrant who was living near-by. What she said was: “Young man, you’ll have to read War and Peace by Tolstoy”. So I read it and realized that we’d sooner get an understanding of what’s going on in Russia from the books of the past rather than the today’s newspapers. Russian culture enthralled me. I began to study the language, the culture and history of Russia. Since I first visited Russia in late 1950s I started to have a feeling that both our peoples have something in common despite the different ways in which our histories have progressed and our countries developed. I think a parallel may be drawn between the discovery and settlement of Siberia in Russia and the American exploration of the West, processes which resulted in our nations meeting in Alaska. The historical roles of the Mississippi and the Volga are also similar. There are other similarities as well.

- The mass media in Russia aren’t giving a clear idea of the relationship between Russia and the USA. At times it seems we’re enemies. How do you look on these relations?

- There are some difficulties but nothing like the Cold war. Our countries have just concluded an agreement on world trade; there’s been development in economic cooperation. We share some views on the situation in the Middle East. On the one hand, things are much better than they used to be in the Soviet times. On the other, the Americans point out a gradual return of the Soviet-time practices: the centralization of power, authoritarianism and high-profile assassinations. This doesn’t foster confidence building between the two countries.

The Russians still know little about us and we know little about them. The mass media doesn’t always show the best. Journalists are after sensations and it’s impossible to see how common people live. Russian society is developing in a complicated evolutionary way. Many Americans think that Russian culture isn’t changing and Russia remains a totalitarian state. But it isn’t so. A generation has emerged that has a positive attitude to America and eagerly deals with their equals in age from abroad. But the contacts are not sufficient. Owing to the Congress sponsored Open World Program more than 11,000 Russians visited the United States and got a kind of understanding of Americans. Russia hasn’t so far come up with a similar initiative. At this stage we know the Chinese better than we know the Russians. America traded with China, we sent our missionaries there. We know the Germans because we’ve twice been at war with them. We got to know Japan. But we didn’t send missionaries to Russia because it was a predominantly Christian country. And we’ve never been at war with you.

- Earlier, in Soviet times, there was a sort of a caste of specialists on Russia, Sovietologists. But today’s Russia is not what it used to be. What’s your and your colleagues’ life like now?

- Well, it isn’t exactly a caste. There have always been a lot of arguments inside that group. The thing is many Sovietologists came from Eastern Europe. They feared the Soviet Union. I, for one, can easily call myself a Russophile. I often came to Russia, worked in archives, met with people. Many of my colleagues didn’t come here that’s why their attitude toward Russian culture was negative. At present there aren’t so many specialists in Russia’s culture as before but interest in Russia and its culture has lately been increasing again. Your country has become more open. Yuri Lotman, Mikhail Bakhtin, Dmitry Likhachev and even Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who isn’t a great admirer of Americans, gave a deeper insight into Russian culture in comparison with the idea many Americans had of it. There’s also a practical dimension to the interest in Russia. Americans can see that your country is becoming increasingly engaged in the international politics. I had a chance to explain some things about Russia and its people to some of our politicians (James Billington accompanied President Ronald Reagan to the 1988 summit in Moscow. – I.K.)

- I’ll cite from your book Russia in Search of Itself: “To find their own way Russians must develop a balanced understanding of their history without extolling either debacle or stagnation.” What future do you think lies ahead for Russia?

- Evolutionary development of the country in contrast to the revolutionary disturbances hasn’t been researched in depth. To look on the country’s history as the history of the empire, of revolutions, repressions and oprichnina is an outdated approach. It isn’t the true history. In particular little is known about life in Russia’s provinces. I, for one, have always been interested in Russia’s North. Not so long ago I wrote a piece about Kizhi in The Wall Street Journal, showing it not as a monument of architecture but as an outlet for the creative power of the Russian province in time of trouble under Peter the Great. I think provinces always took the side of the central authority. We arranged an exhibition devoted to Russian America in the Library of Congress. Cultural development in Alaska had its own way. And that was once the case with Novgorod but unfortunately these traditions are lost.

- Do you think Russia is Europe or Asia?

- In terms of geography part of Russia is Asia. But to my mind the Russians have European mentality. Russia is the inheritor of Byzantine culture and Byzantium was a part of Europe. The history of Europe can’t be fully understood without Russia’s history. Russia is a sort of the eastern boundary of European civilization whereas America is its western boundary.

- Another quotation from the book: “The Russians can’t turn over a new leaf without settling accounts with the past and its repressions and atrocities.” Is this possible?

- It is possible and even inevitable both for people and the state. There are several ways for a nation to make the fact of its mass implication in evil-doing a thing of the past. You can stamp out the problem from public conscience. The Chinese are reluctant to denounce Mao under whom they suffered repressions on a larger scale than the Russians. Or one may put the blame on others like in a classical case of negative nationalism. Or repent.

In South Africa, following the fall of apartheid, a slogan “Truth and Reconciliation” appeared (the government of the Republic of South Africa set up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to inquire into the crimes, committed under apartheid - I.K.) I don’t think there need to be any counter-repressions. Only the truth. So far only half of the truth has been made public. The history of Stalin’s times, of cleansings, hasn’t been written yet. There’s only the history of particular labor camps and a great deal of evidence of the repressed. The picture is not complete. It’s hard to move on without one. We, Americans, waited for the truth about racism, which threw a shadow on our history, for a long time. Reconciliation is also a very difficult thing. But I think that lustration like in Germany and Czechoslovakia is three quarters of the job. It would be a worthy gift from the retiring generation to the young. But the central bureaucratic authority, that survives all the revolutions, always gets in the way.

- Many politicians in Russia say that Stalin was right; judging by the opinion polls, many people are convinced that Stalin has done more good than bad. How can you account for this? Is Russia ready to say good-bye to the past?

- Psychologically it’s understandable. The Soviet Union’s collapse, like any dramatic event, produces a strong impression. Let’s remember the fall of Mongolian Empire, the Roman Empire. You can add to this deteriorating standards of living and corruption. People said then: “What the communists said about communism has proven a lie, and what they said about capitalism has turned out to be the truth.” Besides, the intellectuals had predicted the fall. It’s difficult to come to terms with reality but it’s better than utopian hopes.

And there’s one more aspect. After the defeat of the communist ideology, people started to seek salvation in the economy. They said that free market would put it right and bring about some miraculous changes. But, you know, it’s an oversimplification to explain the economic success of the Western countries after the Second World War by economic determinism. I think that our economic advisors made a mistake by giving the Soviet establishment a ready set of reforms.

- Again, I’m quoting from your book Russia in Search of Itself: “Building a state where there’s the rule of constitution and law is rather an art than science”. Are ready prescriptions for development suitable for Russia?

- I think Russian cultural traditions should be revived. On the other hand, the adopted state and economic institutions need to be transformed and adjusted to Russia’s reality. The Open World Program is based on the Marshall model, the plan for the post-war revival of Europe. That plan included young Germans going to the United States. The institutes of the state power that existed under Nazism were destroyed. The Germans saw how our system worked. And in the end they didn’t copy our institutes mechanically but adapted them to suit the local realities. The Soviet Union, like Germany, had a military-type economy. Germany also had to develop small and medium-sized business. In fact, what’s going on in Russia is the rehearsal of a revival. That’s what happened in post-war Germany, Japan and other Asian “tigers”.

- When do you expect to see the rise of Russia?

- It’s been only 15 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The economic recovery of South Korea took decades of preparation. You shouldn’t expect swift economic growth or a sudden emergence of a multi-partisan political system. Though, in comparison with other countries, Russia is making progress. I believe it’s partially so because of the system of universal education that was a strong part of the Soviet system. That’s why we see a new generation that is comparatively well educated. You’ve just heard a monologue of a former professor who speaks about everything, of which he virtually knows little.

- The role of an intellectual in the Soviet Union was quite definite: it was either a conformist or a dissident. What role is intelligentsia playing now?

- I don’t think it exists any longer as a caste, a social class. I mean educated people, intellectuals, haven’t disappeared of course, but intelligentsia as a phenomenon has. It’s an attribute of freedom. Intelligentsia was beyond all institutes, it was a sort of a secular religion. Nowadays there’s simply no need in it. Of course, there’re people that resist the authoritarian inclinations of the government but they follow formal democratic procedures. And those intellectuals who defend the government aren’t conformists at all. They are more of nationalists than advocates of a strong state.

- And how can you account for the appearance of Russian fascists? Doesn’t it strike you as weird that a country that half a century ago defeated Nazis has now skinheads?

- Remember nihilists! There have always been youngsters that deny everything. And the rise of nationalism isn’t only a Russian phenomenon. The fast development of means of communication always has a negative effect. People insist on being unique, they go for traditionalism. It’s good, on the one hand, but on the other hand it does harm because it feeds crypto-fascism. The situation today resembles the 1840s when the world saw the emergence of telegraph, photography and railways. The paperback revolution took place, mass book printing appeared. Mutual understanding was expected to enhance in Europe. Just before 1848 Karl Marx said that all working people lived and thought in the same way and that they were ready to make a joint stand against capitalism. But just a fortnight after the “Communist manifesto” a wave of nationalist revolutions hit Europe. The liberal reforms of Alexander II in Russia brought into being terrorists. In modern Russia there are nihilist-skinheads. Marx said that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce. It’s of course no laughing matter that skinheads kill people. But from the point of view of a historian it’s like a farce.

- Will skinheads be disappearing?

- In Russia with its messianic idea there’s a risk of appearing a strong nationalist movement, state nationalism. Ideas of Ioann Kronshtadsky, Lev Gumilev, Eurasianists, people, insisting on the biological difference of the Russians from other peoples, have become popular now.

- What’s your vision of Russia in a decade?

- I’d like to see a multicultural country. I hope that Russia’s rich culture will revive, that there will emerge a new Orthodoxy that won’t be apprehensive of pluralism. Commune-related traditions may also revive. I think that ecological conscience in Russia, thanks to Orthodoxy, is more deeply rooted than in the West. I hope that there will appear new political and economic institutes that will result from ingeniously combining Russian and foreign experience. There will be a new open society.

I look on the bright side: I like about Russia what’s not on the surface. Nobody expected the Soviet Union to disband so peacefully. I was in Moscow then. I watched the moral, inner revolution that affected not only the dissidents who had gathered by the White House, but the military as well who didn’t give an order to shoot. In ten years Russia will probably give the rest of the world a surprise.

[Reprinted with Permission]