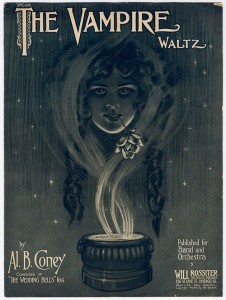

"When that Vampire Rolled her Vampy Eyes at Me." Lee Johnson. Los Angeles: Lee Johnson Music Publishing Co., 1917.

The following is a part one of a guest post by Kevin LaVine, Senior Music Specialist.

If you’ve ever sat around a campfire, listening intently to a ghost story almost against your will; or have peered through half-closed eyes, with fascination and horror, at a slasher film; or have simply heard inexplicable bumps in the night, then you’re already aware that supernatural subjects make for attention-grabbing, and occasionally hair-raising, stories. Unless you’ve been living under a slab, you’ve likely become aware of the tremendous popularity of vampires in films like the Twilight series and Let the Right One In, and the television series True Blood and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. These series are hardly new, however, themselves being the demon spawn of shows as Forever Knight (1992-96), with its vampire-cop-hero (played by actor Geraint Wyn Davies), or the wildly popular Gothic soap opera Dark Shadows (1966-71), which depicted the guilt-ridden vampire Barnabas Collins (played by actor Jonathan Frid), and which influenced supernatural fiction writers such as Anne Rice and Stephen King, as well as film director Tim Burton. The popularity of all these series – as well as of the hundreds of motion pictures depicting vampires which have never ceased being produced since the medium was invented – clearly illustrates the fascination held by the vampire theme on our collective psyche… or simply our willingness to be scared out of our minds.

It is little surprise that supernatural subjects appear in the tales and legends of most world cultures. The inherent drama in tales of sorcerers, witches, ghosts and other otherworldly entities makes such subjects ideally suited to musical settings. Western musical history alone is full of supernatural themes: among the works that readily spring to mind are Modest Musorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain (1867/1886) and Paul Dukas’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1897), both concert works featured in the soundtrack of Walt Disney’s animated classic film Fantasia (1940). But the most dramatic, and occasionally melodramatic, manifestation of the supernatural in music is found in opera, which unites musical, visual, and theatrical elements. From the hellish underworld depicted in Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607), one of the first purely operatic works; to the witches’ chorus in Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (ca. 1688), regarded as the first English-language opera; to the demonic demise of the title character in Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1787) by a spirit seeking revenge for his murder at the hand of the Don; to the numerous versions (both operatic and concert works) of the Faust legend, etc. – Western opera has often relied on supernatural themes to attract and entertain audiences.

It is little surprise that supernatural subjects appear in the tales and legends of most world cultures. The inherent drama in tales of sorcerers, witches, ghosts and other otherworldly entities makes such subjects ideally suited to musical settings. Western musical history alone is full of supernatural themes: among the works that readily spring to mind are Modest Musorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain (1867/1886) and Paul Dukas’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1897), both concert works featured in the soundtrack of Walt Disney’s animated classic film Fantasia (1940). But the most dramatic, and occasionally melodramatic, manifestation of the supernatural in music is found in opera, which unites musical, visual, and theatrical elements. From the hellish underworld depicted in Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607), one of the first purely operatic works; to the witches’ chorus in Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (ca. 1688), regarded as the first English-language opera; to the demonic demise of the title character in Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1787) by a spirit seeking revenge for his murder at the hand of the Don; to the numerous versions (both operatic and concert works) of the Faust legend, etc. – Western opera has often relied on supernatural themes to attract and entertain audiences.

While a whole range of preternatural characters may be found in Western music, the vampire is less common. Despite its ghoulish presence in legends throughout the world since time immemorial, this character appears to have made its operatic début only in the 1820s, with Le Vampire (1826) by Belgian composer Martin-Joseph Mengal, as well as in two separate operas, both titled Der Vampyr and both premièred in 1828, by German composers Heinrich Marschner and Peter Josef von Lindpaintner. These operas were composed in response to an artistic movement that flourished in Germany in the early nineteenth century known as Schauerromantik (“Shudder Romanticism”), an offshoot of the literary and artistic Romantic aesthetic of the time – itself rife with supernatural elements – but with the addition to its dramatic palette of the element of horror. Marschner’s opera has remained in the repertoire since its wildly successful première; the operas of Mengal and Lindpaintner have met with a more… moribund fate.

To be continued …