A century and a half after his death, Henry David Thoreau’s literary output continues unabated, with new versions of his work still in progress. That work has shaped the career of Elizabeth Witherell, who joined the staff of the Thoreau Edition in 1974 and has served as its editor in chief since 1980. Founded in 1966, and now located at the University of California at Santa Barbara, the Thoreau Edition publishes scholarly, definitive texts of Thoreau’s writings. Sixteen volumes in the series have already been published, and Witherell envisions twenty-eight volumes in all. The Thoreau Edition’s current project is a three-volume collection of Thoreau’s correspondence, with the first collection of letters slated for publication next spring.

The letters offer a personal and intimate side of the man most famous as the author of Walden, an account of two years spent in a tiny cabin he built on Walden Pond outside Concord, Massachusetts.

“Thoreau was not a person who revealed himself easily,” says Witherell, offering a view shared by scholars and general readers for generations.

Not that Thoreau’s life lacked documentation. In addition to Walden and a few celebrated travelogs, such as Cape Cod and A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, Thoreau (1817–1862) kept a copious journal that, in a previously published edition, stretched to fourteen volumes and some two million words. But the sheer volume of Thoreau’s prose has, paradoxically, complicated the work of gaining a complete understanding of his personality. The scale of Thoreau’s oeuvre, not easily digested in its entirety, invites selective quotation, tempting readers to pick and choose passages that support their pet theories about him.

David Quammen, a science and nature writer who’s looked to Thoreau for inspiration, put it this way: “In fact, the case of Henry Thoreau stands as proof for the whole notion of human inscrutability. This man told us more of himself than perhaps any other American writer, and still he remains beyond fathoming.”

For nature author Bill McKibben, the question of Thoreau’s true self is obscured not only by the breadth of his writings, but their depth. Take Walden. “Understanding the whole of this book is a hopeless task,” McKibben said. “Its writing resembles nothing so much as Scripture; ideas are condensed to epigrams, four or five to a paragraph. Its magic density yields dozens of different readings—psychological, spiritual, literary, political, cultural.”

Many readers, faced with Thoreau’s enigmatic Yankee persona, have resorted to a kind of pop-culture shorthand for describing his life. As the capsule summary goes, Thoreau was an oddball loner who lived by a lake, writing in praise of nature and against modern progress. But the full story of Thoreau’s life involves subtleties and contradictions that call his popular image into question.

“One misperception that has persisted is that he was a hermit who cared little for others,” says Witherell. “He was active in circulating petitions for neighbors in need. He was attentive to what was going on in the community. He was involved in the Underground Railroad.” In yet another way Thoreau was politically active, penning an essay, “Civil Disobedience,” that would later inform the thinking of Mohandas Gandhi and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

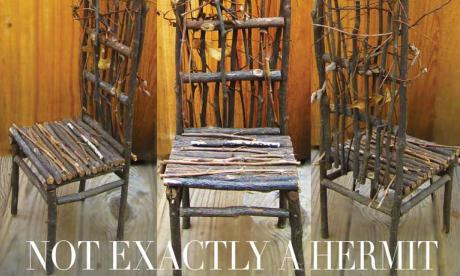

Despite his fame as a champion of solitude—a practice that he chronicled with wisdom and wit, Thoreau made no secret of the social life he indulged during his stay at Walden Pond from 1845 to 1847. In fact, one of the chapters of Walden, titled “Visitors,” offers an extended account of Thoreau’s dealings with others. “I think that I love society as much as most, and am ready enough to fasten myself like a blood- sucker for the time to any full-blooded man that comes in my way,” Thoreau tells readers. “I am naturally no hermit, but might possibly sit out the sturdiest frequenter of the bar- room, if my business called me thither.”

In a subsequent part of “Visitors”—one which ranks among the most-quoted passages in American literature—the lifelong bachelor Thoreau lays out his rules for entertaining:

I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society. When visitors came in larger and unexpected numbers there was but the third chair for them all, but they generally economized the room by standing up. It is surprising how many great men and women a small house will contain. I have had twenty-five or thirty souls, with their bodies, at once under my roof, and yet we often parted without being aware that we had come very near to one another.

With Thoreau’s favorable musings on human company hiding in plain sight, why does his reputation as a monastic scribe persist? “Walden is one of those books . . . that a lot of people have a strong opinion about but don’t really read,” says Witherell.

But even if Thoreau wasn’t always averse to human company, the idea that he was a loner might stem from the assumption that he was the kind of person who should have been alone. He was not, by his own admission, much of a party animal. In a journal passage from 1851, the thirty-four-year-old Thoreau offers a credo for anyone who’s ever been invited out and finds himself wanting to be home instead:

In the evening went to a party. It is a bad place to go,—thirty or forty persons, mostly young women, in a small room, warm and noisy. Was introduced to two young women. The first one was as lively and loquacious as a chickadee; had been accustomed to the society of watering places, and therefore could get no refreshment out of such a dry fellow as I. The other was said to be pretty- looking, but I rarely look people in their faces, and, moreover, I could not hear what she said, there was such a clacking,—could only see the motion of her lips when I looked that way. I could imag- ine better places for conversation, where there should be a certain degree of silence surrounding you, and less than forty talking at once. Why, this afternoon, even, I did better. There was old Mr. Joseph Hossmer and I ate our luncheon of cracker and cheese together in the woods. I heard all he said, though it was not much, to be sure, and he could hear me.

Thoreau was capable of friendship, but on his own terms. “He would be fascinating to know,” says Witherell, “but you wouldn’t want him to be your only friend.” He could be prickly to a fault. “I sometimes hear my Friends complain finely that I do not appreciate their fineness,” he once wrote. “I shall not tell them whether I do or not. As if they expected a vote of thanks for every fine thing which they uttered or did.”

Even those who liked him conceded that Thoreau could be a cold fish. In a letter to his friend Daniel Ricketson in 1860, Thoreau addresses Ricketson’s puzzlement over why he hasn’t come to visit, telling Ricketson, without much ceremony, that he’s had much better things to do. But after explaining himself, Thoreau continued to correspond with Ricketson. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thoreau’s close friend and mentor, who came to grudgingly admire Thoreau’s argumentative streak, famously described him as “not to be subdued, always manly and able, but rarely tender, as if he did not feel himself except in opposition.” In a remembrance of Thoreau, Emerson offered this observation from one of Thoreau’s friends: “I love Henry, but I cannot like him; and as for taking his arm, I should as soon think of taking the arm of an elm-tree.”

But Emerson’s son, Edward Waldo Emerson, who looked to Thoreau as a family uncle and relied on him as a surrogate father when the elder Emerson had to be away on literary business, remembered Thoreau as an engaging nature guide, an expert camper, a gifted magician, and a clever cook who could shake a warming-pan of popcorn over the hearth, then let the “white-blossoming explosion” of kernels “fall over the little people on the rug.”

If Thoreau seemed an ideal boy’s companion, maybe it’s because he never seemed to leave boyhood himself. “I think that no experience which I have to-day comes up to, or is comparable with, the experiences of my boyhood,” Thoreau wrote in 1851. “My life was ecstasy. In youth, before I lost any of my senses, I can remember that I was all alive, and inhabited my body with inexpressible satisfaction; both its weariness and its refreshment were sweet to me. . . . I can remember how I was astonished.”

The premise of Walden—a man adventuring in a hut he builds for himself near a lake—seems like the ultimate boy ’s fantasy, and the convenient proximity of Thoreau’s cabin to friends and neighbors can remind one, a bit wryly, of a child pitching a tent in his parents’ backyard.

The theme seems perfected in the passage of Walden where Thoreau tallies up the homely materials he’s used to build his retreat, including a few boards, throwaway shingles, “two second-hand windows with glass, one thousand old brick,” along with assorted hinges, nails, and other oddments. One sees similar lists in Huckleberry Finn and Robinson Crusoe, two other works with special appeal to males of a tender age. They read like an inventory of the boyhood mind, a pleasant brainstorm of found objects that suggest endless possibility.

Thoreau’s list-making—and his scrupulous accounting of expenses, which allows him to boast of building a cabin for just more than $28—hints at something else. Thoreau could grow impatient with the dry empiricism of finance. “I cannot easily buy a blank-book to write thoughts in,” he lamented, “they are all ruled for dollars and cents.” Yet Thoreau’s intuitive sense of practicality compelled him to keep his own accounting of profit and loss, with a sometimes shrewd eye on the bottom line. Despite his reputation as a dewy-eyed dreamer, Thoreau periodically worked in his family ’s pencil business, implementing innovations that made Thoreau Pencils the finest in America.

A biographical monograph written by Witherell and Elizabeth Dubrulle details Thoreau’s ingenuity in making pencils: “He invented a machine that ground the plumbago for the leads into a very fine powder and developed a combination of the finely ground plumbago and clay that resulted in a pencil that produced a smooth, regular line. He also improved the method of assembling the casing and the lead. Thoreau pencils were the first produced in America that equaled those made by the German company, Faber, whose pencils set the standard for quality.”

Of striking interest in Thoreau’s correspondence, says Witherell, are the business letters on behalf of the family ’s pencil factory, which show a clear grasp of commerce. Thoreau was also sought after as a land surveyor, a job that often supplemented his meager earnings as a writer.

Clearly, Thoreau had options that would have proved more lucrative than a literary career, although the Panic of 1837, an economic downturn with parallels to America’s more recent recession, did limit some of his choices. It was also the year that he graduated from Harvard and began looking for work. He got a teaching post, but resigned after refusing to use corporal punishment on his students. He later opened a private school with his brother John, a venture that eventually folded. “It may have contributed to him becoming a writer,” Witherell says of the economic conditions that depressed the job market for the young Thoreau. “It is possible that if he had been able to get a teaching job, and had been able to teach in the way he wanted to do it, he wouldn’t have had the time to do the writing that he did.”

Because Thoreau’s unconventional path looked nothing like a regular career, his sheer ambition is easy to overlook. His résumé was an eccentric one, to say the least, but he referred to his eclectic pursuits, apparently without irony, as a business:

We are receiving our portion of the infinite. The art of life! . . . I do not remember any page which will tell me how to spend this afternoon. I do not so much wish to know how to economize time as how to spend it. . . .

The scenery, when it is truly seen, reacts on the life of the seer. How to live. How to get the most life. . . . How to extract its honey from the flower of the world. That is my every-day business. I am as busy as a bee about it. I ramble all over the fields on that errand, and am never so happy as when I feel myself heavy with honey and wax.

Such passages seem to foreshadow the era of New Age retreats and mass-market yoga, but one must keep in mind that Thoreau was talking to himself as much as others when he argued for a life of watchful repose. He was a restless man who had to persistently train himself to stand still. He worked very hard at his peculiar vocation, and his industry seemed especially passionate when he put pen to paper. His writing voice, so apparently informal and intuitive, was the result of dogged practice and a zeal for craft.

Thoreau’s prose, which could seem as casually confidential as campfire conversation, came from an author who was a diligent critic of literary style. Here, Thoreau makes the case for economy of expression:

It is the fault of some excellent writers . . . that they express themselves with too great fullness and detail. They give the most faithful, natural, and life- like account of their sensations, mental and physical, but they lack moderation and sententiousness. They do not affect us by an ineffectual earnestness and a reserve of meaning, like a stutterer; they say all they mean. Their sentences are not concentrated and nutty. Sentences which suggest far more than they say, which have an atmosphere about them, which do not merely report an old, but make a new, impression; sentences which suggest as many things and are as durable as a Roman aqueduct; to frame these, that is the art of writing.

What Thoreau is arguing for, and what he advanced by constant example, is a style of writing that’s characteristically American—often colloquial, routinely direct, and with a suggestion of plain talk that sometimes, on second reading, reveals a deeper complexity. E. B. White, an ardent Thoreau fan, praised his writing as “prose at once strictly disciplined and wildly abandoned.”

Here’s one of White’s favorite lines from Walden, in which Thoreau does some imaginary house-shopping among the homesteads of his neighbors:

I walked over each farmer ’s premises, tasted his wild apples, discoursed on husbandry with him, took his farm at his price, at any price, mortgaging it to him in my mind; even put a higher price on it—took everything but a deed of it—took his word for his deed, for I dearly love to talk—cultivated it, and him too to some extent, I trust, and withdrew when I had enjoyed it enough, leaving him to carry it on.

“A copy-desk man would get a double hernia trying to clean up that sentence for the management,” White remarked, “but the sentence needs no fixing, for it perfectly captures the meaning of the writer and the quality of the ramble.”

Thoreau’s writing is also noteworthy for its telegraphic urgency, its insistence on communicating the here and now as if the latest snowfall or bloom on the meadow were a breaking story worthy of the top headline. Thoreau claimed to have little use for daily journalism, but his reports from the countryside around Concord crackle with the deadline intensity of a reporter working a beat. Underlying the passion of his nature narratives is the subtle fear that he might, in spite of his rapt attention, be missing the larger story. “Launched my new boat,” he re- ports in his journal one March day in 1853. “It is very steady, too steady for me; does not toss enough and communicate the motion of the waves.”

Despite his anxieties about not feeling or seeing or knowing enough, we celebrate Thoreau for how little escaped his attention. His observations of the New England countryside are so detailed, in fact, that “they form a data set that has been used by ecologists for research into global warming,” Witherell notes. Thoreau’s concerns about development and its effect on the environment can sound as if they’ve been ripped from this morning’s editorial page. Even after decades of reading him, Witherell says she’s still frequently surprised by how modern he seems. Long before the present wave of concern over Americans’ sedentary lifestyles, to cite but one example, Thoreau offered this observation about the benefits of exercise:

I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements. . . . When sometimes I am reminded that the mechanics and shopkeepers stay in their shops not only all the forenoon, but all the afternoon too, sitting with crossed legs, so many of them,—as if the legs were made to sit upon, and not to stand or walk upon,—I think that they deserve some credit for not having all committed suicide long ago.

Thoreau can, indeed, seem thoroughly contemporary, but unlike so many of today ’s famous public commentators, he doesn’t easily yield to a celebrity profile. As a naturalist, how-to author, political philosopher, amateur scientist, and man of letters, Thoreau defies easy category. “The other misconception about him is that he was only one thing,” Witherell says. “The breadth of knowledge that Thoreau mastered was very diverse. He cannot be described by any single aspect of his activity.”

Perhaps what united his many passions was his commitment to view and document the world around him in all its beauty and complexity. “The question is not what you look at,” Thoreau wrote, “but what you see.”